2 July 2006, Jurançon

Friday, we toured Pau. On the way to the tourist office, we passed the covered market, which is reputed to be an excellent one, so David reluctantly agreed to a short detour through it. He took one step through the door, found himself between a large, dripping fish display on one side (note the size of the prawns, in comparison to, say, the lemons), row upon row of dead poultry with the heads on on the other, and the proud assembled stock of an offal butcher dead ahead, at which point he made a U-turn and went to sit on a park bench while I did my tour.

Friday, we toured Pau. On the way to the tourist office, we passed the covered market, which is reputed to be an excellent one, so David reluctantly agreed to a short detour through it. He took one step through the door, found himself between a large, dripping fish display on one side (note the size of the prawns, in comparison to, say, the lemons), row upon row of dead poultry with the heads on on the other, and the proud assembled stock of an offal butcher dead ahead, at which point he made a U-turn and went to sit on a park bench while I did my tour.

In this photo of a stand selling hot roasted meats, note the head end of a whole roast pig at the lower left and the tail ends of two roast suckling pigs beside it. This photo of a cheese counter shows only about a third of the variety it offered (and Publix thinks it has a good cheese assortment!). Now multiply these by several acres and add in all the other raw-material and prepared food stands, ethnic foods, fruits and vegetables, and so on. And this was just a normal week-day market for established vendors—on Saturdays, the weekly farmers' and producers' market spills across several more acres of parking lot!

In this photo of a stand selling hot roasted meats, note the head end of a whole roast pig at the lower left and the tail ends of two roast suckling pigs beside it. This photo of a cheese counter shows only about a third of the variety it offered (and Publix thinks it has a good cheese assortment!). Now multiply these by several acres and add in all the other raw-material and prepared food stands, ethnic foods, fruits and vegetables, and so on. And this was just a normal week-day market for established vendors—on Saturdays, the weekly farmers' and producers' market spills across several more acres of parking lot!

Once I'd finished a quick once-over of the market, we started our exploration of the town with the tour of the castle of the kings of Navarre, where Henri IV was born. His grandmother, a daughter of François I, had married the king of Navarre, so young Henri was heir to the throne of Navarre (then a separate kingdom) and a cousin of the kings of France. He married Marguerite de Valois (the Queen Margot of the Dumas novelization and later infamous in her own right), sister of the king of France. Through a complicated series of events involving the deaths of the king of France and then of each of his four brothers in turn (and, honest, Henri didn't directly cause any of them), he wound up being designated (by the last brother to die, who was childless) the legitimate heir to the French throne. Not all the various barons and whatnot agreed, of course, especially whoever was Duc de Guise at the time, who always thought it should be him instead, so Henri had several years of military campaigns to carry out before he could consolidate power, which he eventually did (although he had to put aside Queen Margot and marry Marie de Medici to get a legitimate heir). Dumas's novel is made a little hard to follow by the complication that the king of France, his father, the Duc de Guise, and Henri IV were all named Henri.

Once I'd finished a quick once-over of the market, we started our exploration of the town with the tour of the castle of the kings of Navarre, where Henri IV was born. His grandmother, a daughter of François I, had married the king of Navarre, so young Henri was heir to the throne of Navarre (then a separate kingdom) and a cousin of the kings of France. He married Marguerite de Valois (the Queen Margot of the Dumas novelization and later infamous in her own right), sister of the king of France. Through a complicated series of events involving the deaths of the king of France and then of each of his four brothers in turn (and, honest, Henri didn't directly cause any of them), he wound up being designated (by the last brother to die, who was childless) the legitimate heir to the French throne. Not all the various barons and whatnot agreed, of course, especially whoever was Duc de Guise at the time, who always thought it should be him instead, so Henri had several years of military campaigns to carry out before he could consolidate power, which he eventually did (although he had to put aside Queen Margot and marry Marie de Medici to get a legitimate heir). Dumas's novel is made a little hard to follow by the complication that the king of France, his father, the Duc de Guise, and Henri IV were all named Henri.

In the course of his rise to power, he survived the St. Barthelemy massacre, changed religion (from protestant to Catholic and back) four or five times (he's the one who said "Paris is worth a mass"), and left children all over Navarre and France by dozens of documented mistresses, with all of whom he seemed to share sincere affection and lasting attachments. He wasn't called "le vert galant" for nothing. He's also the one who said every peasant should have "son poule au pot le dimanche"—literally, his pot-roasted chicken on Sunday but usually translated "a chicken in every pot." (One of the weekly specials at our dinner restaurant that night was "poule au pot Henri IV.")

But back in Pau, where he was born, to general rejoicing, his cradle was a sea-turtle shell, thought to confer longevity, now displayed under crossed spears in a place of honor in the natal room. Maybe it would have worked (after all, the shell has lasted a long time) if he hadn't been assassinated in his 50s. On the tour, photography without flash was allowed, and our wonderful digital camera did a great job. That's Henri IV himself on the horse.

But back in Pau, where he was born, to general rejoicing, his cradle was a sea-turtle shell, thought to confer longevity, now displayed under crossed spears in a place of honor in the natal room. Maybe it would have worked (after all, the shell has lasted a long time) if he hadn't been assassinated in his 50s. On the tour, photography without flash was allowed, and our wonderful digital camera did a great job. That's Henri IV himself on the horse.

On the tour of the château, we learned for the first time of a technique for making statuary that was in use in Henri's time. The sculpter first built a armature of wood and/or wire, then covered it with layer on layer of papier-maché mixed with powdered stone, building up the desired shape. The surface was then trimmed, molded, and sculpted as desired, some before it dried and more detail afterward. The statue could then be painted, finished, and varnished to look like either marble or bronze. The ones in the château looked like antique bronze, and they sure would have fooled me!

The château is a major national museum and repository of a magnificent collection of tapestries 400 to 500 years old, mostly from the Gobelins studios in Paris. The Gobelins is still in operation and open for tours; they keep all the old patterns in case somebody wants a new set of tapestries run up (they're often commissioned for restoration projects, to replace tapestries that didn't survive, from the original patterns) ; they also have a whole library of trade-secret recipes for the dyes that keep those tapestries so bright after 400 years.

This detail from a much larger tapestry is just part of the trim at the bottom, not even part of the main subject of the scene protrayed. The area shown (about a square meter) would take a tapestry weaver (i.e., a "lissier," not an ordinary weaver, a "tisseur") about a year. The pattern is completely woven in, not embroidered on.

This detail from a much larger tapestry is just part of the trim at the bottom, not even part of the main subject of the scene protrayed. The area shown (about a square meter) would take a tapestry weaver (i.e., a "lissier," not an ordinary weaver, a "tisseur") about a year. The pattern is completely woven in, not embroidered on.

The museum's other major collection is porcelains, including a large collection of elegantly decorated and beautiful Sèvres procelain chamberpots. The guide especially pointed out a series of small, oval chamberpots with handles, nicknamed for some particularly long-winded clergyman whose name I've forgotten. Ladies concealed them in their ample sleeves for discrete use (beneath their full, floor-length skirts) during his notorious 6-hour sermons!

The château (like Château de Brindos) had actual swallows, in addition to the usual swifts. They had white throats and white rumps, but I forget which species that is.

After the tour of the castle, we wandered around the pedestrian shopping streets for a little while before selecting a promising restaurant for our usual composed-salad lunch. I had a particularly good salad of warm chicken livers, coarsely grated apple, and croutons over greens with a creamy vinaigrette.

After lunch, we did the Michelin-recommended walking tour of the town, admired the yellow-and-white, two-towered casino, justly reputed to be among the most beautiful in France, and visited the art museum, which has (among other good stuff) Degas's "Cotton merchant's office in New Orleans." Part of the walk led along a kilometer-long parapet with a panoramic view of the Pyrenees (at least on a clear day, which this one wasn't) and of a large old brick factory complex on the valley floor below. At intervals along the parapet, a little metal plate was attached to the railing with the name of a peak and its altitude. If you lined up the plaque with the factory's tallest smokestack, the slender metal spire mounted on the smokestack's summit pointed exactly to the peak in question!

We stayed a second night in Pau, but our Friday restaurant reservation was at Chez Ruffet, in Jurançon, across the river. The nice lady at the tourist office traced a route for us on the map—it was only 2 or 3 km—avoiding all the construction zones and alerting us to helpful landmarks. We set out confidently from the hotel, heading for the large traffic nexus at the Place Verdun, which would lead us to the bridge we had seen from the ramparts of the castle. But no such luck. At Verdun, we were given no choice of direction but instead shot straight across square, left at the far side, then right at the river, missing our bridge entirely and shooting off west along the near bank, toward Bordeaux! Okay, we'd allowed plenty of time, so we kept on until we found an arrow pointing to Jurançon, which we could clearly see, across the river and already behind us. The arrow plunged us into a tunnel under the railroad, back up and over a different bridge, and off west again, along the far bank, toward Bordeaux! Okay, keep watching for another Jurançon sign. Soon another one did appear, and this one in fact doubled us back in the right direction. I was trying, simultaneously, to study the map and to spot some indication of what street we were on, when suddently a greenspace appeared ahead that could only be the Jurançon town square. Quick, take a (think fast; we're facing southeast) sharp right here! Presto, there we were on the right street, with the restaurant dead ahead and plentiful parking all around. Despite the unexpected detours, we were stll a half-hour early, so we parked the car and went for a stroll along the neighboring branch of the Gave de Pau river. A mother mallard and seven tiny ducklings barely bigger than the eggs they must just have hatched from were working the water weeds, eagerly munching something smaller than we could distinguish. A pair of foot-long, blunt-nosed, rat-tailed mammals (nutrias?) were swimming around near the opposite bank. Swallows were zooming around just above the water surface; these had red throats and no white rumps, barn swallows, I think; anyway, they were a different species from the ones at the castle. [Note added later: I looked them up. The ones with white rumps and throats are Delichon urbica, the "hirondelle de fenêtre" or house martin. The ones with the red throat and dark rump are Hirundo rustica, the "hirondelle de cheminée" or barn swallow.]

We stayed a second night in Pau, but our Friday restaurant reservation was at Chez Ruffet, in Jurançon, across the river. The nice lady at the tourist office traced a route for us on the map—it was only 2 or 3 km—avoiding all the construction zones and alerting us to helpful landmarks. We set out confidently from the hotel, heading for the large traffic nexus at the Place Verdun, which would lead us to the bridge we had seen from the ramparts of the castle. But no such luck. At Verdun, we were given no choice of direction but instead shot straight across square, left at the far side, then right at the river, missing our bridge entirely and shooting off west along the near bank, toward Bordeaux! Okay, we'd allowed plenty of time, so we kept on until we found an arrow pointing to Jurançon, which we could clearly see, across the river and already behind us. The arrow plunged us into a tunnel under the railroad, back up and over a different bridge, and off west again, along the far bank, toward Bordeaux! Okay, keep watching for another Jurançon sign. Soon another one did appear, and this one in fact doubled us back in the right direction. I was trying, simultaneously, to study the map and to spot some indication of what street we were on, when suddently a greenspace appeared ahead that could only be the Jurançon town square. Quick, take a (think fast; we're facing southeast) sharp right here! Presto, there we were on the right street, with the restaurant dead ahead and plentiful parking all around. Despite the unexpected detours, we were stll a half-hour early, so we parked the car and went for a stroll along the neighboring branch of the Gave de Pau river. A mother mallard and seven tiny ducklings barely bigger than the eggs they must just have hatched from were working the water weeds, eagerly munching something smaller than we could distinguish. A pair of foot-long, blunt-nosed, rat-tailed mammals (nutrias?) were swimming around near the opposite bank. Swallows were zooming around just above the water surface; these had red throats and no white rumps, barn swallows, I think; anyway, they were a different species from the ones at the castle. [Note added later: I looked them up. The ones with white rumps and throats are Delichon urbica, the "hirondelle de fenêtre" or house martin. The ones with the red throat and dark rump are Hirundo rustica, the "hirondelle de cheminée" or barn swallow.]

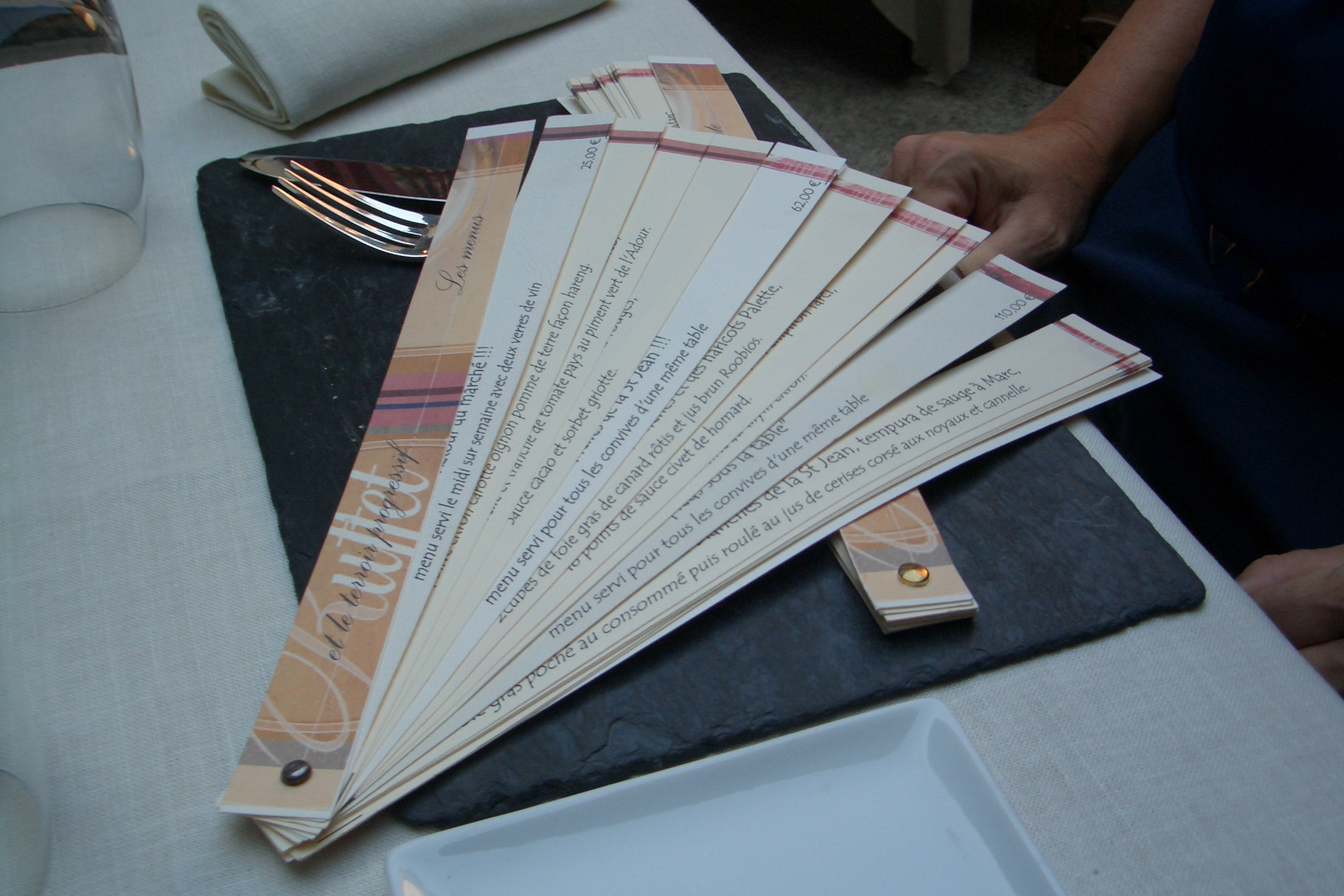

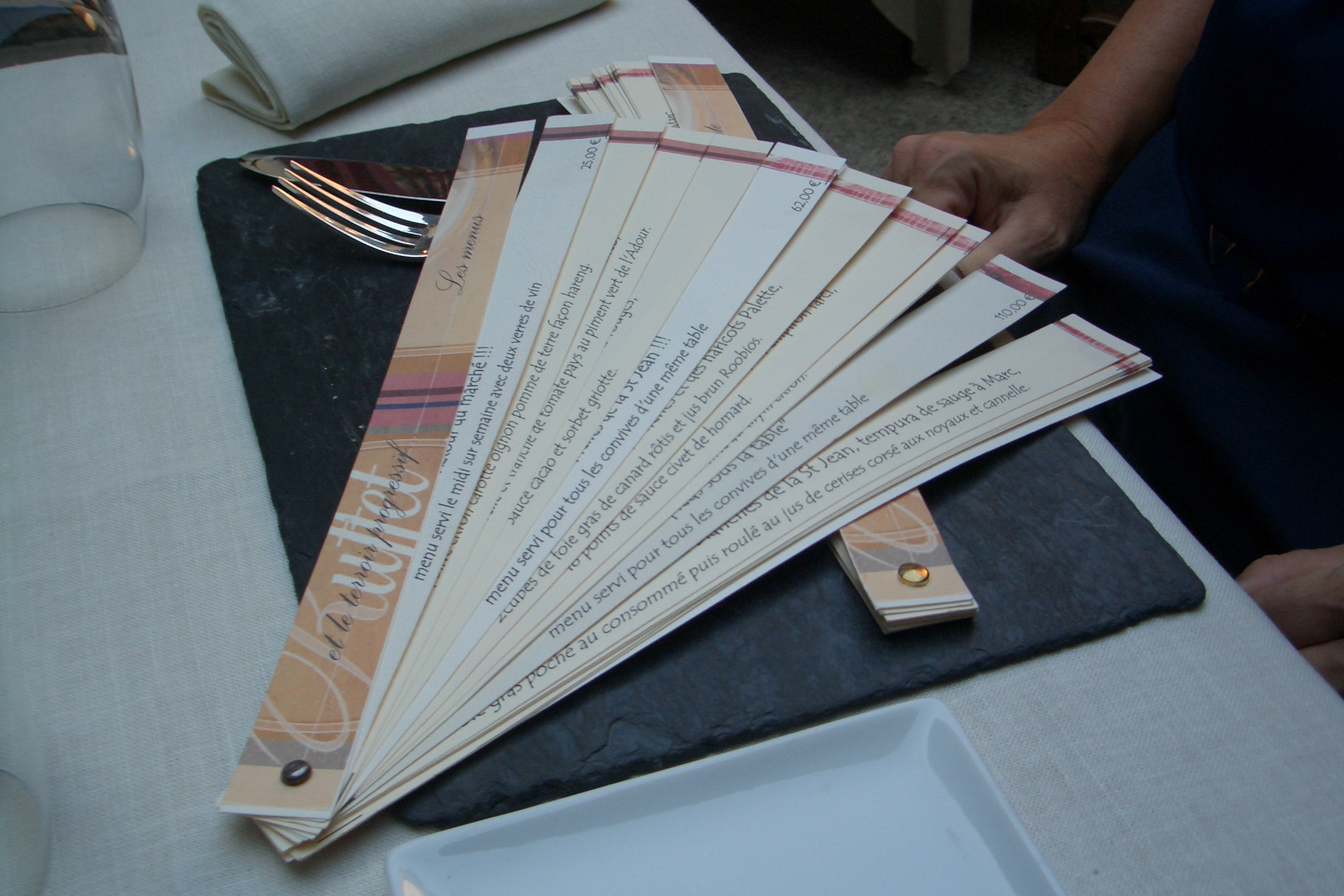

The time passed quickly in the midst of all that wildlife, so we strolled back to the restaurant, which was in just about all ways (except excellence of food) different from Chez Pierre. Instead of a dark, plush, wood-paneled room, we were seated in a flowery stone courtyard. The menus, instead of the 2- by 3-foot pasteboard jobs with no prices on the ladies' copies favored by classicial places, looked like those fan-shaped bundles of paint samples docorators give you. The maitre d' was a cheerful and chatty young man with moussed hair and a pale-gray suit. He was very knowledgeable and enthusiastic about the food, and he tried to tempt us with the special of the day—a special preparation of slices of large, wild-caught turbot—by having a waiter bring forth and show us the actual fish, a 9-kg whopper, carried on a slate slab that must have weighed almost as much as the turbot.

The time passed quickly in the midst of all that wildlife, so we strolled back to the restaurant, which was in just about all ways (except excellence of food) different from Chez Pierre. Instead of a dark, plush, wood-paneled room, we were seated in a flowery stone courtyard. The menus, instead of the 2- by 3-foot pasteboard jobs with no prices on the ladies' copies favored by classicial places, looked like those fan-shaped bundles of paint samples docorators give you. The maitre d' was a cheerful and chatty young man with moussed hair and a pale-gray suit. He was very knowledgeable and enthusiastic about the food, and he tried to tempt us with the special of the day—a special preparation of slices of large, wild-caught turbot—by having a waiter bring forth and show us the actual fish, a 9-kg whopper, carried on a slate slab that must have weighed almost as much as the turbot.

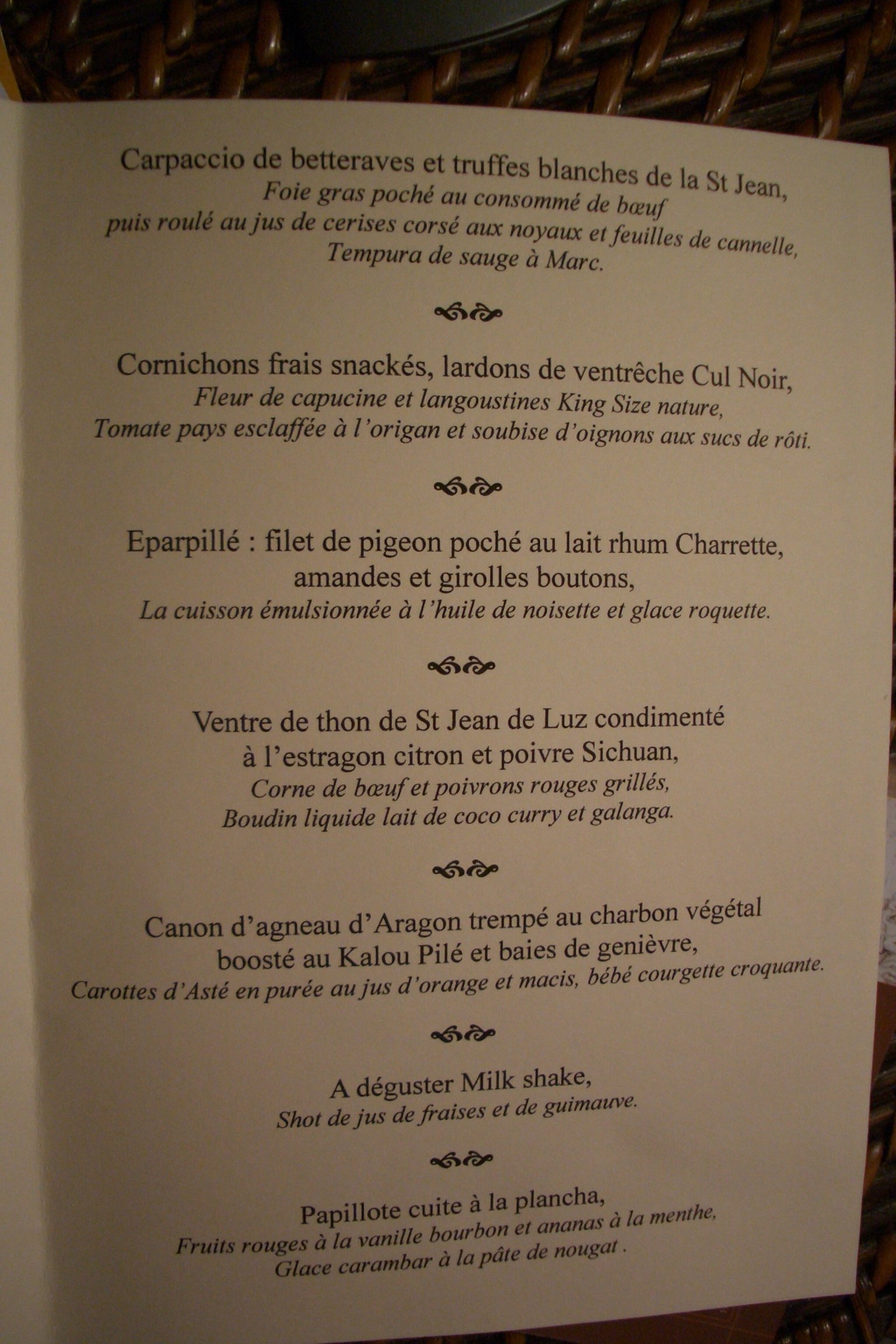

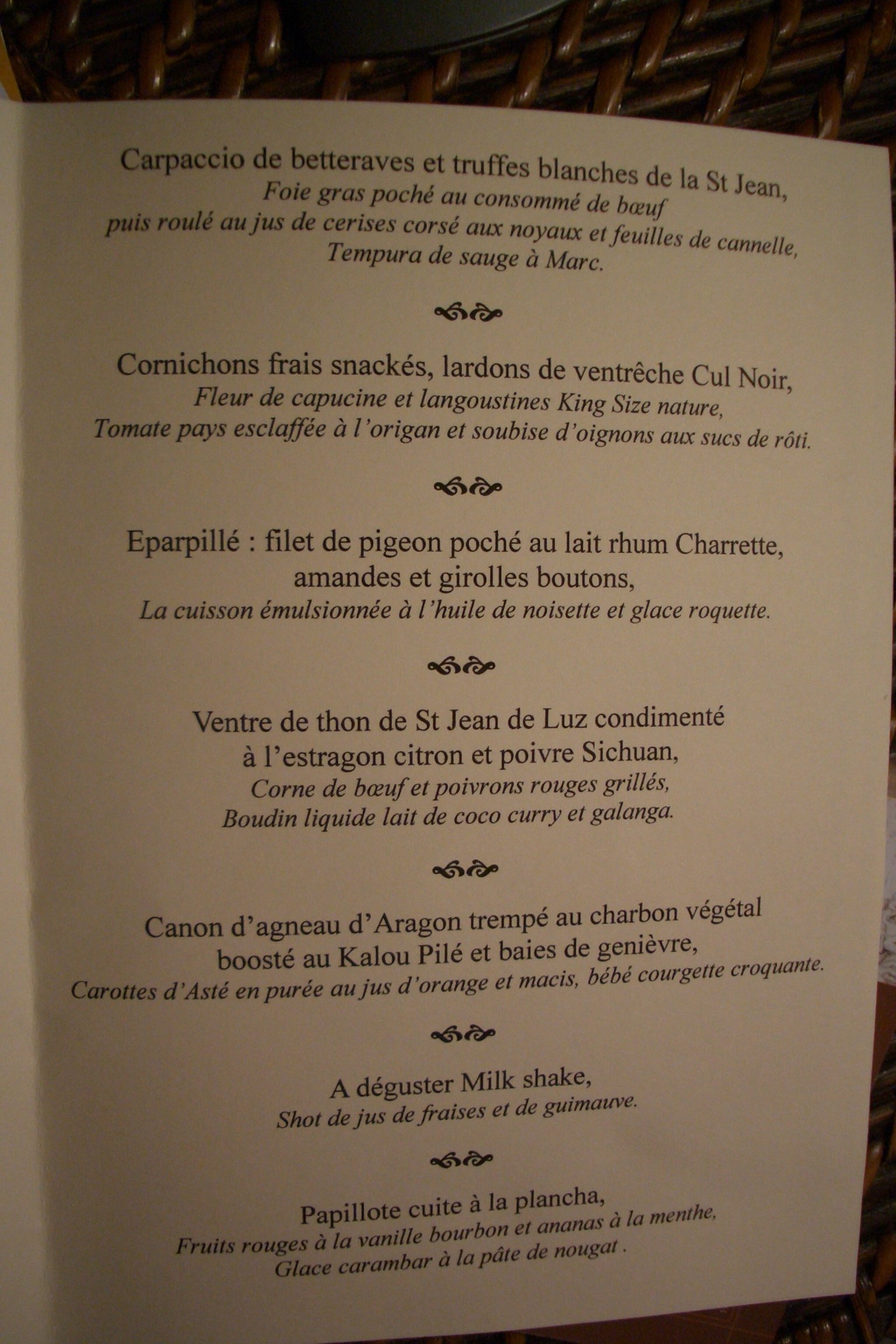

Rather than listing the menu course by course (we passed up the all-truffle menu in favor of the tasting menu; both could be ordered only by all people at the table so we ate the same thing), I'll just post this photo of the souvenir copy they gave us (click the small image for the full-size, readable version). The food was outstanding but could only be described as moderately off-the-wall. For example, the amuse-bouche (not listed on the menu) was in three parts: explosively flavorful goat-cheese fritters on sticks (the sticks were roasted uncooked pasta and tasty in their own right), little packets of raw tuna and vegetables wrapped in thin cucumber slices and held together with clothespins, and little salads each consisting of three peeled halves of "pigeon-heart" cherry tomatoes and a raspberry, all tossed in vinaigrette.

The roast pigeon with chanterelle mushrooms was accompanied by a foamed emulsion of the cooking juices with hazelnut oil and a ball of sweet arugula ice cream. One course involved slices of smoked fresh cucumber. The pre-dessert was a small vanilla milk-shake accompanied by a shot of pure, sweet strawberry juice and a square home-made tomato-and-chili marshmallow.

Rather than listing the menu course by course (we passed up the all-truffle menu in favor of the tasting menu; both could be ordered only by all people at the table so we ate the same thing), I'll just post this photo of the souvenir copy they gave us (click the small image for the full-size, readable version). The food was outstanding but could only be described as moderately off-the-wall. For example, the amuse-bouche (not listed on the menu) was in three parts: explosively flavorful goat-cheese fritters on sticks (the sticks were roasted uncooked pasta and tasty in their own right), little packets of raw tuna and vegetables wrapped in thin cucumber slices and held together with clothespins, and little salads each consisting of three peeled halves of "pigeon-heart" cherry tomatoes and a raspberry, all tossed in vinaigrette.

The roast pigeon with chanterelle mushrooms was accompanied by a foamed emulsion of the cooking juices with hazelnut oil and a ball of sweet arugula ice cream. One course involved slices of smoked fresh cucumber. The pre-dessert was a small vanilla milk-shake accompanied by a shot of pure, sweet strawberry juice and a square home-made tomato-and-chili marshmallow.

At the end of the meal, the mignardises arrived in a wooden shoe-shine box, divided into half a dozen compartments. One held sugar lumps for the coffee, another whole physalis fruits (their "japanese-lantern" calyces folded back and twisted into convenient handles), others held small cookies of different kinds, and one a heap of what looked like cylindrical plugs (about half an inch in diameter by an inch long) punched from an old truck tire, which the waiter presented proudly as locally made organic licorice. I tried one and, wow! I had forgotten!, that was the licorice of my childhood, not the wimpy, sweet, plastic-textured shoelaces and twists you get now. Even though I had just eaten a triple amuse-bouche and seven courses, I couldn't stop popping those little pellets, and I restrained myself with difficulty from emptying the box into my purse for later. No wonder old truck tires have always looked more appetizing to me than would seem entirely reasonable.

At the end of the meal, the mignardises arrived in a wooden shoe-shine box, divided into half a dozen compartments. One held sugar lumps for the coffee, another whole physalis fruits (their "japanese-lantern" calyces folded back and twisted into convenient handles), others held small cookies of different kinds, and one a heap of what looked like cylindrical plugs (about half an inch in diameter by an inch long) punched from an old truck tire, which the waiter presented proudly as locally made organic licorice. I tried one and, wow! I had forgotten!, that was the licorice of my childhood, not the wimpy, sweet, plastic-textured shoelaces and twists you get now. Even though I had just eaten a triple amuse-bouche and seven courses, I couldn't stop popping those little pellets, and I restrained myself with difficulty from emptying the box into my purse for later. No wonder old truck tires have always looked more appetizing to me than would seem entirely reasonable.

We managed to get back to the hotel by the route we'd intended to take the other way, and we encountered no one-way streets, so I don't know why it was so important to the road-sign people that we go to Jurançon by the long way 'round.

previous entry List of Entries next entry

In this photo of a stand selling hot roasted meats, note the head end of a whole roast pig at the lower left and the tail ends of two roast suckling pigs beside it. This photo of a cheese counter shows only about a third of the variety it offered (and Publix thinks it has a good cheese assortment!). Now multiply these by several acres and add in all the other raw-material and prepared food stands, ethnic foods, fruits and vegetables, and so on. And this was just a normal week-day market for established vendors—on Saturdays, the weekly farmers' and producers' market spills across several more acres of parking lot!

In this photo of a stand selling hot roasted meats, note the head end of a whole roast pig at the lower left and the tail ends of two roast suckling pigs beside it. This photo of a cheese counter shows only about a third of the variety it offered (and Publix thinks it has a good cheese assortment!). Now multiply these by several acres and add in all the other raw-material and prepared food stands, ethnic foods, fruits and vegetables, and so on. And this was just a normal week-day market for established vendors—on Saturdays, the weekly farmers' and producers' market spills across several more acres of parking lot! Friday, we toured Pau. On the way to the tourist office, we passed the covered market, which is reputed to be an excellent one, so David reluctantly agreed to a short detour through it. He took one step through the door, found himself between a large, dripping fish display on one side (note the size of the prawns, in comparison to, say, the lemons), row upon row of dead poultry with the heads on on the other, and the proud assembled stock of an offal butcher dead ahead, at which point he made a U-turn and went to sit on a park bench while I did my tour.

Friday, we toured Pau. On the way to the tourist office, we passed the covered market, which is reputed to be an excellent one, so David reluctantly agreed to a short detour through it. He took one step through the door, found himself between a large, dripping fish display on one side (note the size of the prawns, in comparison to, say, the lemons), row upon row of dead poultry with the heads on on the other, and the proud assembled stock of an offal butcher dead ahead, at which point he made a U-turn and went to sit on a park bench while I did my tour.  Once I'd finished a quick once-over of the market, we started our exploration of the town with the tour of the castle of the kings of Navarre, where Henri IV was born. His grandmother, a daughter of François I, had married the king of Navarre, so young Henri was heir to the throne of Navarre (then a separate kingdom) and a cousin of the kings of France. He married Marguerite de Valois (the Queen Margot of the Dumas novelization and later infamous in her own right), sister of the king of France. Through a complicated series of events involving the deaths of the king of France and then of each of his four brothers in turn (and, honest, Henri didn't directly cause any of them), he wound up being designated (by the last brother to die, who was childless) the legitimate heir to the French throne. Not all the various barons and whatnot agreed, of course, especially whoever was Duc de Guise at the time, who always thought it should be him instead, so Henri had several years of military campaigns to carry out before he could consolidate power, which he eventually did (although he had to put aside Queen Margot and marry Marie de Medici to get a legitimate heir). Dumas's novel is made a little hard to follow by the complication that the king of France, his father, the Duc de Guise, and Henri IV were all named Henri.

Once I'd finished a quick once-over of the market, we started our exploration of the town with the tour of the castle of the kings of Navarre, where Henri IV was born. His grandmother, a daughter of François I, had married the king of Navarre, so young Henri was heir to the throne of Navarre (then a separate kingdom) and a cousin of the kings of France. He married Marguerite de Valois (the Queen Margot of the Dumas novelization and later infamous in her own right), sister of the king of France. Through a complicated series of events involving the deaths of the king of France and then of each of his four brothers in turn (and, honest, Henri didn't directly cause any of them), he wound up being designated (by the last brother to die, who was childless) the legitimate heir to the French throne. Not all the various barons and whatnot agreed, of course, especially whoever was Duc de Guise at the time, who always thought it should be him instead, so Henri had several years of military campaigns to carry out before he could consolidate power, which he eventually did (although he had to put aside Queen Margot and marry Marie de Medici to get a legitimate heir). Dumas's novel is made a little hard to follow by the complication that the king of France, his father, the Duc de Guise, and Henri IV were all named Henri.

But back in Pau, where he was born, to general rejoicing, his cradle was a sea-turtle shell, thought to confer longevity, now displayed under crossed spears in a place of honor in the natal room. Maybe it would have worked (after all, the shell has lasted a long time) if he hadn't been assassinated in his 50s. On the tour, photography without flash was allowed, and our wonderful digital camera did a great job. That's Henri IV himself on the horse.

But back in Pau, where he was born, to general rejoicing, his cradle was a sea-turtle shell, thought to confer longevity, now displayed under crossed spears in a place of honor in the natal room. Maybe it would have worked (after all, the shell has lasted a long time) if he hadn't been assassinated in his 50s. On the tour, photography without flash was allowed, and our wonderful digital camera did a great job. That's Henri IV himself on the horse.  This detail from a much larger tapestry is just part of the trim at the bottom, not even part of the main subject of the scene protrayed. The area shown (about a square meter) would take a tapestry weaver (i.e., a "lissier," not an ordinary weaver, a "tisseur") about a year. The pattern is completely woven in, not embroidered on.

This detail from a much larger tapestry is just part of the trim at the bottom, not even part of the main subject of the scene protrayed. The area shown (about a square meter) would take a tapestry weaver (i.e., a "lissier," not an ordinary weaver, a "tisseur") about a year. The pattern is completely woven in, not embroidered on. We stayed a second night in Pau, but our Friday restaurant reservation was at Chez Ruffet, in Jurançon, across the river. The nice lady at the tourist office traced a route for us on the map—it was only 2 or 3 km—avoiding all the construction zones and alerting us to helpful landmarks. We set out confidently from the hotel, heading for the large traffic nexus at the Place Verdun, which would lead us to the bridge we had seen from the ramparts of the castle. But no such luck. At Verdun, we were given no choice of direction but instead shot straight across square, left at the far side, then right at the river, missing our bridge entirely and shooting off west along the near bank, toward Bordeaux! Okay, we'd allowed plenty of time, so we kept on until we found an arrow pointing to Jurançon, which we could clearly see, across the river and already behind us. The arrow plunged us into a tunnel under the railroad, back up and over a different bridge, and off west again, along the far bank, toward Bordeaux! Okay, keep watching for another Jurançon sign. Soon another one did appear, and this one in fact doubled us back in the right direction. I was trying, simultaneously, to study the map and to spot some indication of what street we were on, when suddently a greenspace appeared ahead that could only be the Jurançon town square. Quick, take a (think fast; we're facing southeast) sharp right here! Presto, there we were on the right street, with the restaurant dead ahead and plentiful parking all around. Despite the unexpected detours, we were stll a half-hour early, so we parked the car and went for a stroll along the neighboring branch of the Gave de Pau river. A mother mallard and seven tiny ducklings barely bigger than the eggs they must just have hatched from were working the water weeds, eagerly munching something smaller than we could distinguish. A pair of foot-long, blunt-nosed, rat-tailed mammals (nutrias?) were swimming around near the opposite bank. Swallows were zooming around just above the water surface; these had red throats and no white rumps, barn swallows, I think; anyway, they were a different species from the ones at the castle. [Note added later: I looked them up. The ones with white rumps and throats are Delichon urbica, the "hirondelle de fenêtre" or house martin. The ones with the red throat and dark rump are Hirundo rustica, the "hirondelle de cheminée" or barn swallow.]

We stayed a second night in Pau, but our Friday restaurant reservation was at Chez Ruffet, in Jurançon, across the river. The nice lady at the tourist office traced a route for us on the map—it was only 2 or 3 km—avoiding all the construction zones and alerting us to helpful landmarks. We set out confidently from the hotel, heading for the large traffic nexus at the Place Verdun, which would lead us to the bridge we had seen from the ramparts of the castle. But no such luck. At Verdun, we were given no choice of direction but instead shot straight across square, left at the far side, then right at the river, missing our bridge entirely and shooting off west along the near bank, toward Bordeaux! Okay, we'd allowed plenty of time, so we kept on until we found an arrow pointing to Jurançon, which we could clearly see, across the river and already behind us. The arrow plunged us into a tunnel under the railroad, back up and over a different bridge, and off west again, along the far bank, toward Bordeaux! Okay, keep watching for another Jurançon sign. Soon another one did appear, and this one in fact doubled us back in the right direction. I was trying, simultaneously, to study the map and to spot some indication of what street we were on, when suddently a greenspace appeared ahead that could only be the Jurançon town square. Quick, take a (think fast; we're facing southeast) sharp right here! Presto, there we were on the right street, with the restaurant dead ahead and plentiful parking all around. Despite the unexpected detours, we were stll a half-hour early, so we parked the car and went for a stroll along the neighboring branch of the Gave de Pau river. A mother mallard and seven tiny ducklings barely bigger than the eggs they must just have hatched from were working the water weeds, eagerly munching something smaller than we could distinguish. A pair of foot-long, blunt-nosed, rat-tailed mammals (nutrias?) were swimming around near the opposite bank. Swallows were zooming around just above the water surface; these had red throats and no white rumps, barn swallows, I think; anyway, they were a different species from the ones at the castle. [Note added later: I looked them up. The ones with white rumps and throats are Delichon urbica, the "hirondelle de fenêtre" or house martin. The ones with the red throat and dark rump are Hirundo rustica, the "hirondelle de cheminée" or barn swallow.] The time passed quickly in the midst of all that wildlife, so we strolled back to the restaurant, which was in just about all ways (except excellence of food) different from Chez Pierre. Instead of a dark, plush, wood-paneled room, we were seated in a flowery stone courtyard. The menus, instead of the 2- by 3-foot pasteboard jobs with no prices on the ladies' copies favored by classicial places, looked like those fan-shaped bundles of paint samples docorators give you. The maitre d' was a cheerful and chatty young man with moussed hair and a pale-gray suit. He was very knowledgeable and enthusiastic about the food, and he tried to tempt us with the special of the day—a special preparation of slices of large, wild-caught turbot—by having a waiter bring forth and show us the actual fish, a 9-kg whopper, carried on a slate slab that must have weighed almost as much as the turbot.

The time passed quickly in the midst of all that wildlife, so we strolled back to the restaurant, which was in just about all ways (except excellence of food) different from Chez Pierre. Instead of a dark, plush, wood-paneled room, we were seated in a flowery stone courtyard. The menus, instead of the 2- by 3-foot pasteboard jobs with no prices on the ladies' copies favored by classicial places, looked like those fan-shaped bundles of paint samples docorators give you. The maitre d' was a cheerful and chatty young man with moussed hair and a pale-gray suit. He was very knowledgeable and enthusiastic about the food, and he tried to tempt us with the special of the day—a special preparation of slices of large, wild-caught turbot—by having a waiter bring forth and show us the actual fish, a 9-kg whopper, carried on a slate slab that must have weighed almost as much as the turbot.

At the end of the meal, the mignardises arrived in a wooden shoe-shine box, divided into half a dozen compartments. One held sugar lumps for the coffee, another whole physalis fruits (their "japanese-lantern" calyces folded back and twisted into convenient handles), others held small cookies of different kinds, and one a heap of what looked like cylindrical plugs (about half an inch in diameter by an inch long) punched from an old truck tire, which the waiter presented proudly as locally made organic licorice. I tried one and, wow! I had forgotten!, that was the licorice of my childhood, not the wimpy, sweet, plastic-textured shoelaces and twists you get now. Even though I had just eaten a triple amuse-bouche and seven courses, I couldn't stop popping those little pellets, and I restrained myself with difficulty from emptying the box into my purse for later. No wonder old truck tires have always looked more appetizing to me than would seem entirely reasonable.

At the end of the meal, the mignardises arrived in a wooden shoe-shine box, divided into half a dozen compartments. One held sugar lumps for the coffee, another whole physalis fruits (their "japanese-lantern" calyces folded back and twisted into convenient handles), others held small cookies of different kinds, and one a heap of what looked like cylindrical plugs (about half an inch in diameter by an inch long) punched from an old truck tire, which the waiter presented proudly as locally made organic licorice. I tried one and, wow! I had forgotten!, that was the licorice of my childhood, not the wimpy, sweet, plastic-textured shoelaces and twists you get now. Even though I had just eaten a triple amuse-bouche and seven courses, I couldn't stop popping those little pellets, and I restrained myself with difficulty from emptying the box into my purse for later. No wonder old truck tires have always looked more appetizing to me than would seem entirely reasonable.