Wednesday, 28 May 2008, Breakfast in Châlons

(Written 28 May 2008)

The Michelin Guide says that the proprietor of the Pot d'Etain used to be a baker and prides himself on the hotel's impeccable breakfast, and they're right. Many places now include a glass of orange juice with the continental breakfast. It usually comes ready-poured, and we usually ignore it, David because it's so acid and me because my blood sugar is high enough in the mornings as is. Here, when you sit down, even by yourself, they whip out a quart bottle of chilled OJ and give you the whole thing, with a tiny glass (later comers get the recapped left-over half bottles, but I'm sure that anyone who ran out would immediately be offered a fresh bottle) . I was able to catch the waitress before she opened it and refuse it, so she offered instead, and I accepted with delight, a chilled half-liter of Evian. Then she assembled a pastry basket for me from a lovely display behind the counter—for one person, you get a miniature baguette, freshly split, and one each pain au chocolat, croissant, pain aux raisins, and delice au chocolate, all miniature of course. Each table is preset with butter, sugar, and two kinds of jam, but on the bar are baskets of extra jam, butter, sugar, Nutella, whole fruit (apples, bananas, kiwi, oranges, grapefruit), several prepackaged cheeses, and two kinds of cereal. I ordered, and got, an excellent decaf café au lait. An impeccable breakfast indeed.

The Michelin Guide says that the proprietor of the Pot d'Etain used to be a baker and prides himself on the hotel's impeccable breakfast, and they're right. Many places now include a glass of orange juice with the continental breakfast. It usually comes ready-poured, and we usually ignore it, David because it's so acid and me because my blood sugar is high enough in the mornings as is. Here, when you sit down, even by yourself, they whip out a quart bottle of chilled OJ and give you the whole thing, with a tiny glass (later comers get the recapped left-over half bottles, but I'm sure that anyone who ran out would immediately be offered a fresh bottle) . I was able to catch the waitress before she opened it and refuse it, so she offered instead, and I accepted with delight, a chilled half-liter of Evian. Then she assembled a pastry basket for me from a lovely display behind the counter—for one person, you get a miniature baguette, freshly split, and one each pain au chocolat, croissant, pain aux raisins, and delice au chocolate, all miniature of course. Each table is preset with butter, sugar, and two kinds of jam, but on the bar are baskets of extra jam, butter, sugar, Nutella, whole fruit (apples, bananas, kiwi, oranges, grapefruit), several prepackaged cheeses, and two kinds of cereal. I ordered, and got, an excellent decaf café au lait. An impeccable breakfast indeed.

(Written 31 May 2008)

First order of business was to head off to Epernay to retrieve David's Tilley hat, which we did successfully. The staff at the Ibis must have really gotten a kick out of it, because we found all the adjustments of its straps changed and the brim snapped up to the crown on both sides.

From there, we set off along the "Route Touristique de la Champagne," which rather than being a single circuit seems to lead everywhere in the Champagne region. The section we followed led south from Epernay (past the chocolat place we'd toured) through what's called the "Côte des Blancs," the north-facing slopes on the south bank of the Marne, where the Chardonnay grapes (the only white ones used for champagne) are grown. Surrounded by vinyards on all sides, we passed through the little villages of Cuis, Cramant, Avize, Oger, and Menil sur Oger on our way to Vertus. Road construction in Avize send us on an elaborate detour out through the unpaved lanes the winegrowers use to reach the vines, so we got within arm's length of the vines themselves. Everywhere we looked, the vinyards were dotted with parked white vans—winegrowers were out in the vinyards doing something. The vines weren't being sprayed, and the growing-season trimming is done by machine now, so we speculated that they were walking the rows repairing trellis wires—mending fences, at it were. We passed a number of "stilt tractors," designed to straddle a row of vines and to trim it, spray it, or whatever is needed. )I'm not sure whether the grapes are harvested by machine or still by hand.) The one shown here (with the line of traffic passing it) is double-size, designed to straddle two rows.

From there, we set off along the "Route Touristique de la Champagne," which rather than being a single circuit seems to lead everywhere in the Champagne region. The section we followed led south from Epernay (past the chocolat place we'd toured) through what's called the "Côte des Blancs," the north-facing slopes on the south bank of the Marne, where the Chardonnay grapes (the only white ones used for champagne) are grown. Surrounded by vinyards on all sides, we passed through the little villages of Cuis, Cramant, Avize, Oger, and Menil sur Oger on our way to Vertus. Road construction in Avize send us on an elaborate detour out through the unpaved lanes the winegrowers use to reach the vines, so we got within arm's length of the vines themselves. Everywhere we looked, the vinyards were dotted with parked white vans—winegrowers were out in the vinyards doing something. The vines weren't being sprayed, and the growing-season trimming is done by machine now, so we speculated that they were walking the rows repairing trellis wires—mending fences, at it were. We passed a number of "stilt tractors," designed to straddle a row of vines and to trim it, spray it, or whatever is needed. )I'm not sure whether the grapes are harvested by machine or still by hand.) The one shown here (with the line of traffic passing it) is double-size, designed to straddle two rows.

At each crossroads in the villages, a sign like this one directed passers-by to the premises of the nearest champagne houses. This signpost is especially large because Vertus is larger than the other villages, but the ones in the smaller villages differed in having fewer signs pointing to other towns, not in the number of little signs like those at the bottom pointing to champagne makers. Some of the champagne establishments had nicely decorated entrances like this one; others were just stone buildings with hundred-year-old brass plaques on their doors. Many had signs in the form of 3D models of a champagne bottles (about the size of the one in the photo); the label on each served to identify the maker.

At each crossroads in the villages, a sign like this one directed passers-by to the premises of the nearest champagne houses. This signpost is especially large because Vertus is larger than the other villages, but the ones in the smaller villages differed in having fewer signs pointing to other towns, not in the number of little signs like those at the bottom pointing to champagne makers. Some of the champagne establishments had nicely decorated entrances like this one; others were just stone buildings with hundred-year-old brass plaques on their doors. Many had signs in the form of 3D models of a champagne bottles (about the size of the one in the photo); the label on each served to identify the maker.

We reached Vertus at about noon, so we went to the Hotel Thibault IV for lunch. The clientel was an interesting mixture—a champagne maker and his local son, plus a son visiting from the city with his girlfriend; a group of half a dozen champagne makers who seemed to meet there regularly; a couple of other pairs of tourists (mostly French, but a British couple were seated next to us); several single men with fat expandable files under their arms, whom we took to be "négociants" and wine buyers, out working the territory. The buyers were pretty quiet, but everyone else seemed to have a great time, and conversation was lively, including a certain amount of banter with the proprietor.

I had an excellent salad smothered in warm snails and lardons, in a cream sauce. David had slices of duck magret (uncharacteristically moist; more like corned duck than duck ham) over cold, lightly cooked vegetables and a salad of local lentils, also with a delicious creamy sauce. Both smaller than usual French salads, but just about what we wanted.

I had an excellent salad smothered in warm snails and lardons, in a cream sauce. David had slices of duck magret (uncharacteristically moist; more like corned duck than duck ham) over cold, lightly cooked vegetables and a salad of local lentils, also with a delicious creamy sauce. Both smaller than usual French salads, but just about what we wanted.

(Written 1 June 2008)

From Vertus, we turned north again and crossed back over the Marne into the Pinot Noir area, on the south-facing slopes of the north bank, and drove to Suippes (pronounced "sweep") to visit a museum David was particularly interested in. It was smaller than we expected from its publicity brochure, and we were the only visitors there (outnumbered by the staff), but it was very effective. It used mainly period photos and newspaper clippings to take the visitor through the war from before the beginning (the tensions that led to war) to after the end (the difficulties of reconstruction, the social disruption, the medical sequellae, etc.), with particular emphasis on the area surrounding Suippes and Reims.

Another item emphasized in the pubicity brochure was the "biometric stations," and sure enough, at the beginning of the visit, right before the 12-minute introductory film, we were shown how to place our thumbs on a little electronic fingerprint reader. The machine scanned our prints and assigned each of us an identity. David was a soldier whose father happened to be a famous French politician. I was a middle-aged nurse living in Biarritz. (These were real people about whose war experience a lot happened to be known.) The idea was that, as we moved through the museum, each time we came to a biometric station and presented our thumbs, the machine would read them, recognize us, and tell us what our alter egos were doing at that stage of the war and where. Strangely, though, we came to only one such station in the whole museum—perhaps the system is not yet finished. Throughout the visit, though, we encountered real, period field telephones of many different designs, mounted on the walls. Each one let you listen to a different song sung by the troops or important politic speech of the period.

The photos and clippings were supplemented by relics, old uniforms, helmets, weapons, etc., including this "artisanal" mortar, constructed from a spent German shell casing. Someone had clearly given a great deal of thought to the presentation. One special feature was a tabletop on which a ceiling projector displayed an animated map of the front. It proceeding through the whole course of the war, showing the major troop movements, battles, and advances and retreats of the front, zooming in or out and from side to side as appropriate to show additional detail. Another feature was a room furnished to resemble the interior of a trench. We sat on sandbags during a three-minute multimedia presentation that simulated the sights and sounds of battle, including a movie overhead that showed the steadily falling rain and on which we could see the smoke trails of shells before hearing them land and explode.

The photos and clippings were supplemented by relics, old uniforms, helmets, weapons, etc., including this "artisanal" mortar, constructed from a spent German shell casing. Someone had clearly given a great deal of thought to the presentation. One special feature was a tabletop on which a ceiling projector displayed an animated map of the front. It proceeding through the whole course of the war, showing the major troop movements, battles, and advances and retreats of the front, zooming in or out and from side to side as appropriate to show additional detail. Another feature was a room furnished to resemble the interior of a trench. We sat on sandbags during a three-minute multimedia presentation that simulated the sights and sounds of battle, including a movie overhead that showed the steadily falling rain and on which we could see the smoke trails of shells before hearing them land and explode.

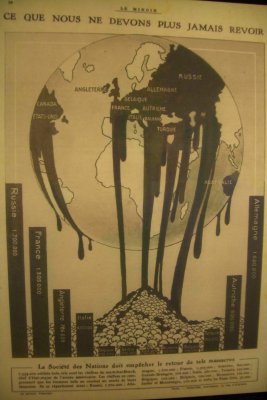

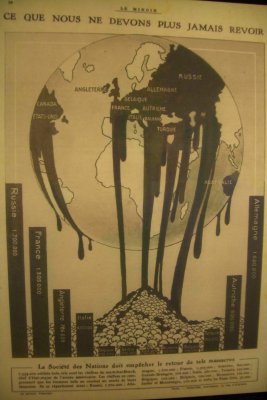

Here's an especially striking newspaper graphic from the period after the war, showing the numbers of dead from each country involved. Russia is at the left (1.7 million), then France (1.3 million). Germany is at the right (1.6 million). The U.S. is in the very middle with 50,000, the only country down into five figures. The headline reads "That which we must never see again."

Here's an especially striking newspaper graphic from the period after the war, showing the numbers of dead from each country involved. Russia is at the left (1.7 million), then France (1.3 million). Germany is at the right (1.6 million). The U.S. is in the very middle with 50,000, the only country down into five figures. The headline reads "That which we must never see again."

Back in Châlons, we had dinner at Jacky Michel again. On the way, we walked past it major WWI memorial, dedicated as usual to local men and boys who died for France. We happened to notice that this one shows a much higher ratio than usual of WWII to WWI dead. The WWI names are on the wings to the sides of the central sculpture; those from WWII are on the sides of the sculpture's base. The WWI names still outnumber those from WWII, but only by about 2 to 1.

Back in Châlons, we had dinner at Jacky Michel again. On the way, we walked past it major WWI memorial, dedicated as usual to local men and boys who died for France. We happened to notice that this one shows a much higher ratio than usual of WWII to WWI dead. The WWI names are on the wings to the sides of the central sculpture; those from WWII are on the sides of the sculpture's base. The WWI names still outnumber those from WWII, but only by about 2 to 1.

Back at Jack Michel, we resolved to go easy, remembering the size of the portions the night before—just a main course and dessert each. David was wavering, suggesting we split a starter, when the waiter walked by carrying the whole stuffed roasted onion and beef tartare amuse bouche, bringing us back to our senses. Knowing we'd been there the night before, though, they altered our amuse-bouche.

Amuse-bouche 1, both: A demitasse of very hot cream of white asparagus soup. Delicious.

Amuse-bouche 2, both: A cylindrical timbale very similar to the one from the night before, but this time featuring tuna tartare. Excellent. (I had thought wistfully of the tuna tartare starter but resisted.)

Amuse-bouche 2, both: A cylindrical timbale very similar to the one from the night before, but this time featuring tuna tartare. Excellent. (I had thought wistfully of the tuna tartare starter but resisted.)

Main couse, David: Sole with mousseron mushrooms, freshly made pasta, and champagne cream sauce (which came with its own special glass of white wine).

Main couse, David: Sole with mousseron mushrooms, freshly made pasta, and champagne cream sauce (which came with its own special glass of white wine).

Main course, me: Veal sweetbreads, napped with an intense dark reduction sauce and accompanied by white asparagus, mousseron mushrooms and morels in a rich cream sauce, and a very thin slice of crisp bacon. Outstanding! I'm really glad that chefs have gone back to the classic preparations of sweetbreads.

Main course, me: Veal sweetbreads, napped with an intense dark reduction sauce and accompanied by white asparagus, mousseron mushrooms and morels in a rich cream sauce, and a very thin slice of crisp bacon. Outstanding! I'm really glad that chefs have gone back to the classic preparations of sweetbreads.

Dessert, David: Caramelized dome of semolina pudding resting on a layer of crême patissière, in turn resting on chopped red fruit, all surrounded by a pool of smooth green purée of stewed rhubarb.

Dessert, David: Caramelized dome of semolina pudding resting on a layer of crême patissière, in turn resting on chopped red fruit, all surrounded by a pool of smooth green purée of stewed rhubarb.

Dessert, me: Hot chocolate soufflé; what can you say?

Mignardises: This time, we had exercised sufficient restraint to partake of at least a few mignardises from the assortment. David went for more chocolates; I had another tuile and a sugared square of black current fruit paste.

After dinner, we took a stroll up the canal toward what I was pretty sure was the spot near a little wooded island where our hotel barge had tied up back in 1988. I remembered sitting on the deck after dinner, watching a nutria (Myocastor coypus) swim by—nutrias, usually called "coypus" in Europe, to avoid confusion with the Spanish name for the otter (and also called "ragondins" in France)—was introduced from South America by fur ranchers and is usually considered a nuisance where it has escaped (e.g., in Louisiana). This year, as we approached the little wooded island at dusk, sure enough, a nutria swam by! We figure it for the great-grand-offspring of the one we saw from the barge.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

The Michelin Guide says that the proprietor of the Pot d'Etain used to be a baker and prides himself on the hotel's impeccable breakfast, and they're right. Many places now include a glass of orange juice with the continental breakfast. It usually comes ready-poured, and we usually ignore it, David because it's so acid and me because my blood sugar is high enough in the mornings as is. Here, when you sit down, even by yourself, they whip out a quart bottle of chilled OJ and give you the whole thing, with a tiny glass (later comers get the recapped left-over half bottles, but I'm sure that anyone who ran out would immediately be offered a fresh bottle) . I was able to catch the waitress before she opened it and refuse it, so she offered instead, and I accepted with delight, a chilled half-liter of Evian. Then she assembled a pastry basket for me from a lovely display behind the counter—for one person, you get a miniature baguette, freshly split, and one each pain au chocolat, croissant, pain aux raisins, and delice au chocolate, all miniature of course. Each table is preset with butter, sugar, and two kinds of jam, but on the bar are baskets of extra jam, butter, sugar, Nutella, whole fruit (apples, bananas, kiwi, oranges, grapefruit), several prepackaged cheeses, and two kinds of cereal. I ordered, and got, an excellent decaf café au lait. An impeccable breakfast indeed.

The Michelin Guide says that the proprietor of the Pot d'Etain used to be a baker and prides himself on the hotel's impeccable breakfast, and they're right. Many places now include a glass of orange juice with the continental breakfast. It usually comes ready-poured, and we usually ignore it, David because it's so acid and me because my blood sugar is high enough in the mornings as is. Here, when you sit down, even by yourself, they whip out a quart bottle of chilled OJ and give you the whole thing, with a tiny glass (later comers get the recapped left-over half bottles, but I'm sure that anyone who ran out would immediately be offered a fresh bottle) . I was able to catch the waitress before she opened it and refuse it, so she offered instead, and I accepted with delight, a chilled half-liter of Evian. Then she assembled a pastry basket for me from a lovely display behind the counter—for one person, you get a miniature baguette, freshly split, and one each pain au chocolat, croissant, pain aux raisins, and delice au chocolate, all miniature of course. Each table is preset with butter, sugar, and two kinds of jam, but on the bar are baskets of extra jam, butter, sugar, Nutella, whole fruit (apples, bananas, kiwi, oranges, grapefruit), several prepackaged cheeses, and two kinds of cereal. I ordered, and got, an excellent decaf café au lait. An impeccable breakfast indeed. From there, we set off along the "Route Touristique de la Champagne," which rather than being a single circuit seems to lead everywhere in the Champagne region. The section we followed led south from Epernay (past the chocolat place we'd toured) through what's called the "Côte des Blancs," the north-facing slopes on the south bank of the Marne, where the Chardonnay grapes (the only white ones used for champagne) are grown. Surrounded by vinyards on all sides, we passed through the little villages of Cuis, Cramant, Avize, Oger, and Menil sur Oger on our way to Vertus. Road construction in Avize send us on an elaborate detour out through the unpaved lanes the winegrowers use to reach the vines, so we got within arm's length of the vines themselves. Everywhere we looked, the vinyards were dotted with parked white vans—winegrowers were out in the vinyards doing something. The vines weren't being sprayed, and the growing-season trimming is done by machine now, so we speculated that they were walking the rows repairing trellis wires—mending fences, at it were. We passed a number of "stilt tractors," designed to straddle a row of vines and to trim it, spray it, or whatever is needed. )I'm not sure whether the grapes are harvested by machine or still by hand.) The one shown here (with the line of traffic passing it) is double-size, designed to straddle two rows.

From there, we set off along the "Route Touristique de la Champagne," which rather than being a single circuit seems to lead everywhere in the Champagne region. The section we followed led south from Epernay (past the chocolat place we'd toured) through what's called the "Côte des Blancs," the north-facing slopes on the south bank of the Marne, where the Chardonnay grapes (the only white ones used for champagne) are grown. Surrounded by vinyards on all sides, we passed through the little villages of Cuis, Cramant, Avize, Oger, and Menil sur Oger on our way to Vertus. Road construction in Avize send us on an elaborate detour out through the unpaved lanes the winegrowers use to reach the vines, so we got within arm's length of the vines themselves. Everywhere we looked, the vinyards were dotted with parked white vans—winegrowers were out in the vinyards doing something. The vines weren't being sprayed, and the growing-season trimming is done by machine now, so we speculated that they were walking the rows repairing trellis wires—mending fences, at it were. We passed a number of "stilt tractors," designed to straddle a row of vines and to trim it, spray it, or whatever is needed. )I'm not sure whether the grapes are harvested by machine or still by hand.) The one shown here (with the line of traffic passing it) is double-size, designed to straddle two rows.

At each crossroads in the villages, a sign like this one directed passers-by to the premises of the nearest champagne houses. This signpost is especially large because Vertus is larger than the other villages, but the ones in the smaller villages differed in having fewer signs pointing to other towns, not in the number of little signs like those at the bottom pointing to champagne makers. Some of the champagne establishments had nicely decorated entrances like this one; others were just stone buildings with hundred-year-old brass plaques on their doors. Many had signs in the form of 3D models of a champagne bottles (about the size of the one in the photo); the label on each served to identify the maker.

At each crossroads in the villages, a sign like this one directed passers-by to the premises of the nearest champagne houses. This signpost is especially large because Vertus is larger than the other villages, but the ones in the smaller villages differed in having fewer signs pointing to other towns, not in the number of little signs like those at the bottom pointing to champagne makers. Some of the champagne establishments had nicely decorated entrances like this one; others were just stone buildings with hundred-year-old brass plaques on their doors. Many had signs in the form of 3D models of a champagne bottles (about the size of the one in the photo); the label on each served to identify the maker.

I had an excellent salad smothered in warm snails and lardons, in a cream sauce. David had slices of duck magret (uncharacteristically moist; more like corned duck than duck ham) over cold, lightly cooked vegetables and a salad of local lentils, also with a delicious creamy sauce. Both smaller than usual French salads, but just about what we wanted.

I had an excellent salad smothered in warm snails and lardons, in a cream sauce. David had slices of duck magret (uncharacteristically moist; more like corned duck than duck ham) over cold, lightly cooked vegetables and a salad of local lentils, also with a delicious creamy sauce. Both smaller than usual French salads, but just about what we wanted. The photos and clippings were supplemented by relics, old uniforms, helmets, weapons, etc., including this "artisanal" mortar, constructed from a spent German shell casing. Someone had clearly given a great deal of thought to the presentation. One special feature was a tabletop on which a ceiling projector displayed an animated map of the front. It proceeding through the whole course of the war, showing the major troop movements, battles, and advances and retreats of the front, zooming in or out and from side to side as appropriate to show additional detail. Another feature was a room furnished to resemble the interior of a trench. We sat on sandbags during a three-minute multimedia presentation that simulated the sights and sounds of battle, including a movie overhead that showed the steadily falling rain and on which we could see the smoke trails of shells before hearing them land and explode.

The photos and clippings were supplemented by relics, old uniforms, helmets, weapons, etc., including this "artisanal" mortar, constructed from a spent German shell casing. Someone had clearly given a great deal of thought to the presentation. One special feature was a tabletop on which a ceiling projector displayed an animated map of the front. It proceeding through the whole course of the war, showing the major troop movements, battles, and advances and retreats of the front, zooming in or out and from side to side as appropriate to show additional detail. Another feature was a room furnished to resemble the interior of a trench. We sat on sandbags during a three-minute multimedia presentation that simulated the sights and sounds of battle, including a movie overhead that showed the steadily falling rain and on which we could see the smoke trails of shells before hearing them land and explode. Here's an especially striking newspaper graphic from the period after the war, showing the numbers of dead from each country involved. Russia is at the left (1.7 million), then France (1.3 million). Germany is at the right (1.6 million). The U.S. is in the very middle with 50,000, the only country down into five figures. The headline reads "That which we must never see again."

Here's an especially striking newspaper graphic from the period after the war, showing the numbers of dead from each country involved. Russia is at the left (1.7 million), then France (1.3 million). Germany is at the right (1.6 million). The U.S. is in the very middle with 50,000, the only country down into five figures. The headline reads "That which we must never see again." Back in Châlons, we had dinner at Jacky Michel again. On the way, we walked past it major WWI memorial, dedicated as usual to local men and boys who died for France. We happened to notice that this one shows a much higher ratio than usual of WWII to WWI dead. The WWI names are on the wings to the sides of the central sculpture; those from WWII are on the sides of the sculpture's base. The WWI names still outnumber those from WWII, but only by about 2 to 1.

Back in Châlons, we had dinner at Jacky Michel again. On the way, we walked past it major WWI memorial, dedicated as usual to local men and boys who died for France. We happened to notice that this one shows a much higher ratio than usual of WWII to WWI dead. The WWI names are on the wings to the sides of the central sculpture; those from WWII are on the sides of the sculpture's base. The WWI names still outnumber those from WWII, but only by about 2 to 1. Amuse-bouche 2, both: A cylindrical timbale very similar to the one from the night before, but this time featuring tuna tartare. Excellent. (I had thought wistfully of the tuna tartare starter but resisted.)

Amuse-bouche 2, both: A cylindrical timbale very similar to the one from the night before, but this time featuring tuna tartare. Excellent. (I had thought wistfully of the tuna tartare starter but resisted.) Main couse, David: Sole with mousseron mushrooms, freshly made pasta, and champagne cream sauce (which came with its own special glass of white wine).

Main couse, David: Sole with mousseron mushrooms, freshly made pasta, and champagne cream sauce (which came with its own special glass of white wine). Main course, me: Veal sweetbreads, napped with an intense dark reduction sauce and accompanied by white asparagus, mousseron mushrooms and morels in a rich cream sauce, and a very thin slice of crisp bacon. Outstanding! I'm really glad that chefs have gone back to the classic preparations of sweetbreads.

Main course, me: Veal sweetbreads, napped with an intense dark reduction sauce and accompanied by white asparagus, mousseron mushrooms and morels in a rich cream sauce, and a very thin slice of crisp bacon. Outstanding! I'm really glad that chefs have gone back to the classic preparations of sweetbreads. Dessert, David: Caramelized dome of semolina pudding resting on a layer of crême patissière, in turn resting on chopped red fruit, all surrounded by a pool of smooth green purée of stewed rhubarb.

Dessert, David: Caramelized dome of semolina pudding resting on a layer of crême patissière, in turn resting on chopped red fruit, all surrounded by a pool of smooth green purée of stewed rhubarb.