Thursday, 11 June 2009, Art in Dijon

Written 12 June 2009

First priority on Thursday was the Musée des Beaux Arts, in the ducal palace, but we stopped on the way to watch two guys in a high-reach cherrypicker working on the cleaning and restoration of the Church of St. Bénigne (of the 100 bell towers of Dijon, its is the highest, at 93 m—in my opinion, none of the towers is high enough; the ordinary buildings are so tall, and the streets so narrow, that it's hard to spot landmarks to orient yourself by). The photo on the left shows the contrast between the lower section, already cleaned, and the upper section, where the crane is working, which is still dark with lichen, smoke, and mildew. The close-up on the right shows the two guys chipping loose and removing a damaged collonette for restoration. They checked each collonette for stability, then removed any that were loose and seemed likely to fall, taking careful before-and-after pictures each time.

First priority on Thursday was the Musée des Beaux Arts, in the ducal palace, but we stopped on the way to watch two guys in a high-reach cherrypicker working on the cleaning and restoration of the Church of St. Bénigne (of the 100 bell towers of Dijon, its is the highest, at 93 m—in my opinion, none of the towers is high enough; the ordinary buildings are so tall, and the streets so narrow, that it's hard to spot landmarks to orient yourself by). The photo on the left shows the contrast between the lower section, already cleaned, and the upper section, where the crane is working, which is still dark with lichen, smoke, and mildew. The close-up on the right shows the two guys chipping loose and removing a damaged collonette for restoration. They checked each collonette for stability, then removed any that were loose and seemed likely to fall, taking careful before-and-after pictures each time.

Further on our way, we happened to pass a hat shop, where David was finally able to acquire a good-quality Panama to replace the one that went astray two summers ago in Houston. He's been wearing a cheap one he got last year in Verdun but hasn't been able to find a good quality one that suited him. This new one is almost as nice as the original.

At the museum, we had hoped to start by visiting the ducal kitchens, but they were still closed. I asked at the museum desk when they might be open, and the answer, with a shrug, was "maybe tomorrow." So we just started on the museum, which (signs proclaim everywhere) is free of charge, to everyone, every day. Good deal. Unfortunately, large parts of it are closed for a major renovation (including all art from about 1850 to the present). We passed on the pay-to-view temporary exhibit of "The Hungarian Fauves: The Lesson of Matisse" and just concentrated on the permanent collection, walking all the way to the end of the exhibit and then working our way back.

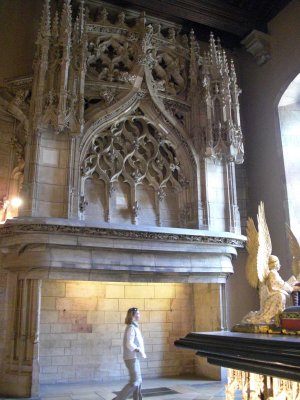

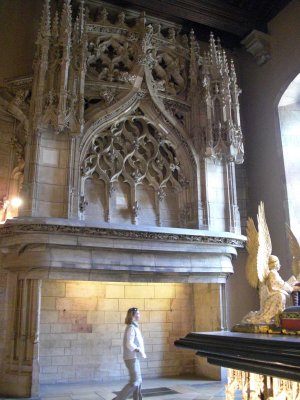

That put us, right off the bat, in the "Salle de Garde," a magnificent hall with a fireplace I could stand up in, with a foot to spare, topped by magnificent flamboyant gothic stone carving. The ducal kitchen apparently has four fireplaces that big (although not as ornate), each large enough to burn cordwood and roast an entire ox. Besides a good deal of religious art, including several large alterpieces carved in high relief, the room houses the tombs of the first two of the "grand ducs"—Philipe le Hardi and Jean Sans Peur (and John's wife, Marguerite de Bavière, i.e., Margaret of Bavaria). Reclining effigies of the deceased rested, at about head height, lions crouching at their feet and angels hovering at their heads, on an elaborately carved base, and "elaborately carved" is an understatement. A procession of figures, first the clergy, then the rest of the ducal court, all dressed in mourning and weeping, runs all the way around each one, within a carved collonade. The figures are very white—I think they're made of marble or alabaster. You can see a little of one side below Philipe's head here, and below all of one side, in the photo of Margaret's reclining effigy. The tombs are the work of three successive sculptors who worked on them for years; the most famous was Klaus Sluter, from the Netherlands. His contribution to the arts of Dijon was so large that a statue of him, hammer and chisel in hand, stands in a courtyard of the palace.

That put us, right off the bat, in the "Salle de Garde," a magnificent hall with a fireplace I could stand up in, with a foot to spare, topped by magnificent flamboyant gothic stone carving. The ducal kitchen apparently has four fireplaces that big (although not as ornate), each large enough to burn cordwood and roast an entire ox. Besides a good deal of religious art, including several large alterpieces carved in high relief, the room houses the tombs of the first two of the "grand ducs"—Philipe le Hardi and Jean Sans Peur (and John's wife, Marguerite de Bavière, i.e., Margaret of Bavaria). Reclining effigies of the deceased rested, at about head height, lions crouching at their feet and angels hovering at their heads, on an elaborately carved base, and "elaborately carved" is an understatement. A procession of figures, first the clergy, then the rest of the ducal court, all dressed in mourning and weeping, runs all the way around each one, within a carved collonade. The figures are very white—I think they're made of marble or alabaster. You can see a little of one side below Philipe's head here, and below all of one side, in the photo of Margaret's reclining effigy. The tombs are the work of three successive sculptors who worked on them for years; the most famous was Klaus Sluter, from the Netherlands. His contribution to the arts of Dijon was so large that a statue of him, hammer and chisel in hand, stands in a courtyard of the palace.

Much of the museum's holdings consist of gruesome Medieval religious art, like this "Temptation of St. Anthony"

from a 14th century altarpiece by Jacques de Baerze. Anthony is beset by two ugly devils and a lovely young woman. At least he's not bleeding to death or being eaten alive like some of the others.

Much of the museum's holdings consist of gruesome Medieval religious art, like this "Temptation of St. Anthony"

from a 14th century altarpiece by Jacques de Baerze. Anthony is beset by two ugly devils and a lovely young woman. At least he's not bleeding to death or being eaten alive like some of the others.

But they did have some things more to our taste. In particular, François Rude is a favorite son of Dijon. He is most famous for his relief of "La Marseillaise" for the Arc de Triomphe in Paris (right-hand side, as you face the arch from the Champs Elysées; he worked on the Arc for years), some studies for which are in the museum. His Hebe is also lovely (just Google-Image "Francois Rude Hebe" for several images, one taken in the room where we saw her). The museum housed a lot of his work, as well as many portraits and statues of him.

After an hour or two in the museum, we turned in our audioguides, getting a little notation on our tickets so that we could pick them up again later without paying the fee again, and set off in search of lunch, which we found at the Brasserie du Théatre. I had a salad of confit duck gizzards and poached eggs (unusual in that the gizzards were left whole rather than sliced up and that the eggs were molded rather than free-form. David had the "salade gourmande." a gigantic conconction topped with toast, slabs of cold foie gras, two duck "sleeves" (i.e., "upper arms" of the wing, stewed to tenderness), a poached egg, and slices of duck-breast ham (you can see two of them, edged with white fat, between the egg and the leftmost tomato). (It was a bit much—great at the time, but on the way home from our equally huge dinner that night, David said, "Okay, bread and water tomorrow.")

After an hour or two in the museum, we turned in our audioguides, getting a little notation on our tickets so that we could pick them up again later without paying the fee again, and set off in search of lunch, which we found at the Brasserie du Théatre. I had a salad of confit duck gizzards and poached eggs (unusual in that the gizzards were left whole rather than sliced up and that the eggs were molded rather than free-form. David had the "salade gourmande." a gigantic conconction topped with toast, slabs of cold foie gras, two duck "sleeves" (i.e., "upper arms" of the wing, stewed to tenderness), a poached egg, and slices of duck-breast ham (you can see two of them, edged with white fat, between the egg and the leftmost tomato). (It was a bit much—great at the time, but on the way home from our equally huge dinner that night, David said, "Okay, bread and water tomorrow.")

Back at the museum, we finished off the rest of the area that was open. One highlight was a portrait by Nattier that, as usual, you could spot across the room as his work. The clothing and background were in darker colors than are typical of him, but the face was unmistakable. Nattier was in great demand as a portraitist because his works managed, simultaneously, to look just like the subject and to be extremely flattering. We have a poster of one in our livingroom that we got at the Jacquemart-André museum in Paris a few years ago. In the Egyptian room, I thought the most interesting item was this mummy of a cat. Finally a 19th century painting of the Salle des Gardes by Auguste Mathieu gives a better view of the room than we could manage. Apparently those works on the left-hand wall were never actually hung there; the artist just assembled his favorites from elsewhere in the museum and added them to his painting (I like that assortment a lot better than the grim altarpieces that do occupy that wall). Also, at present, the nearer tomb is oriented differently, with the angels at the far end rather than the near. Otherwise, that's pretty much what it looks like.

Back at the museum, we finished off the rest of the area that was open. One highlight was a portrait by Nattier that, as usual, you could spot across the room as his work. The clothing and background were in darker colors than are typical of him, but the face was unmistakable. Nattier was in great demand as a portraitist because his works managed, simultaneously, to look just like the subject and to be extremely flattering. We have a poster of one in our livingroom that we got at the Jacquemart-André museum in Paris a few years ago. In the Egyptian room, I thought the most interesting item was this mummy of a cat. Finally a 19th century painting of the Salle des Gardes by Auguste Mathieu gives a better view of the room than we could manage. Apparently those works on the left-hand wall were never actually hung there; the artist just assembled his favorites from elsewhere in the museum and added them to his painting (I like that assortment a lot better than the grim altarpieces that do occupy that wall). Also, at present, the nearer tomb is oriented differently, with the angels at the far end rather than the near. Otherwise, that's pretty much what it looks like.

On the way back to the hotel, we stopped in to have a look at the covered market. The timing never worked out for a visit while it was in operation—everything was closed down and the last of the clean-up was in progress when we were there—but its cast-iron architecture was worth a look. It has apparently not been altered since the market was built (in the Age of Eiffel).

On the way back to the hotel, we stopped in to have a look at the covered market. The timing never worked out for a visit while it was in operation—everything was closed down and the last of the clean-up was in progress when we were there—but its cast-iron architecture was worth a look. It has apparently not been altered since the market was built (in the Age of Eiffel).

After resting up back at our room, we set off by car for our dinner venue, in the little town of Prenois ("turn left on the D104 at the little airport"), called "l'Auberge de la Charme" (Inn of the Hornbeam Tree). Coincidentally, right next to our car in the hotel parking lot, I was able to get this nice shot of a charme tree. The only one we saw at the restaurant was a little sapling recently planted in a flower bed.

The restuarant's decor was simple and modern, despite the age of its building and its exposed beams. The beams and walls had been painted silver—a lovely effect, but as David pointed out, a bear to change if they ever wanted the beams to be bare wood again.

The dinner was also lovely. It started with a four-part amuse-bouche: a cromesqui of pied de porc (pig's foot) resting on a cloud of mild mustard mousse, a tiny crispy black sandwich of tuna, a tomato fougasse (a buttery little orange-red bread bun), and a porcelain spoon containing a minute "stacked salade niçoise" (a slice of a tiny new potato, a slice of grape tomato, a slice of a hard-cooked quail's egg, a dab of mayonnaise, a sliver of black olive, and the tiniest possible sliver of anchovy, all threaded on a toothpick and forming a single mouthful). We then proceeded to the "Menu de la charme."

First course: An egg "cooked at low temperature"—to be precise, an egg cooked in the shell, in the oven, at exactly 61oC (= 141oF) for an hour—resting on a bed of braised sweet bell peppers, in turn resting on a bed of long-stewed tomatoes, topped with a crisp slice of pork belly, and surrounded by an emulsion of smoked bacon. Also, of course, the ubiquitous dots of balsamic vinegar syrup. The egg shimmied like the softest jelly, and as you can see, the white was almost transparent, but it was evenly congealed throughout, and the yolk was semiliquid and creamy. Excellent.

First course: An egg "cooked at low temperature"—to be precise, an egg cooked in the shell, in the oven, at exactly 61oC (= 141oF) for an hour—resting on a bed of braised sweet bell peppers, in turn resting on a bed of long-stewed tomatoes, topped with a crisp slice of pork belly, and surrounded by an emulsion of smoked bacon. Also, of course, the ubiquitous dots of balsamic vinegar syrup. The egg shimmied like the softest jelly, and as you can see, the white was almost transparent, but it was evenly congealed throughout, and the yolk was semiliquid and creamy. Excellent.

Second course, four "munchies," two of snails and two of "cancoillotes" (local bite-sized processed-cheese balls). All four were presented as perfectly spherical hot croquettes, the snails green with parsley and the cheese brown with bread crumbs, and were accompanied by a small stemmed glass of "aiguo boulido" (creamy garlic-thyme soup) to be sipped through a little black straw. The soup in particular was delicious.

Third course: A single gigantic Spanish shrimp described as "snackée" ("snacked," which I took to mean lightly smoked, like kippers), accompanied by artichoke purée, baby artichoke hearts in a light tomato sauce, a poached kumquat, a crisp sweetened lemon slice, and various purées and sauces of lemon and kumquat. Very good.

Third course: A single gigantic Spanish shrimp described as "snackée" ("snacked," which I took to mean lightly smoked, like kippers), accompanied by artichoke purée, baby artichoke hearts in a light tomato sauce, a poached kumquat, a crisp sweetened lemon slice, and various purées and sauces of lemon and kumquat. Very good.

Fourth course: Sweetbreads braised, grilled, and buried under a shower of tiny spring vegetables and braised red onions, all surrounded by a lemon-ginger emulsion. Very good, but I've had better treatments of sweetbreads.

Fourth course: Sweetbreads braised, grilled, and buried under a shower of tiny spring vegetables and braised red onions, all surrounded by a lemon-ginger emulsion. Very good, but I've had better treatments of sweetbreads.

Fifth course: "Deconstructed onion soup"—difficult to photograph but the best dish of the meal. We were served a hot bowl in which were stacked a mound of braised onions so tender they were almost melting together, a layer of minute crisp croutons, a scoop of onion ice cream (very lightly sweetened), a thin slice of Comté cheese, and a crisp toasted "onion chip," all sorrounded by a foamy emulsion. At the table, the waiter poured hot beef broth around the whole thing. Delicious! I'm going to have to try that onion-ice-cream thing at home.

Sixth course, cheese: I choose Chaource, Gaperon with garlic and pepper, and galet de la Loire. That last was new to me, and I didn't care for it (the rind had aged to the ammoniac stage). The Gaperon was good but would have been even better without the garlic and pepper. David chose Chaource, a Swiss gruyère, and a blue we haven't encountered before and whose name we didn't catch ("persillé" de something).

Seventh course, dessert and mignardises: The dessert was great. It consisted of a square of strawberry claffouti, vanilla ice cream, a strawberry tuile cookie, strawberry-fromage-blanc fluff, and a mixture of "fraises des bois" (French wild strawberries, picked that day from the wild by the chef) and gariguettes (my second-favorite variety of French domestic strawberries) sweetened with a light coating of strawberry syrup. Yum! The shiny comet-shaped object is a small blanched almond half dipped into sugar cooked to the molten-glass stage and pulled out to form a long, decorative tail.

Seventh course, dessert and mignardises: The dessert was great. It consisted of a square of strawberry claffouti, vanilla ice cream, a strawberry tuile cookie, strawberry-fromage-blanc fluff, and a mixture of "fraises des bois" (French wild strawberries, picked that day from the wild by the chef) and gariguettes (my second-favorite variety of French domestic strawberries) sweetened with a light coating of strawberry syrup. Yum! The shiny comet-shaped object is a small blanched almond half dipped into sugar cooked to the molten-glass stage and pulled out to form a long, decorative tail.

The mignardises were cherry macaroons, house-made blue-Curaçao marshmallows, absolutely delicious coffee fluff topped with whipped cream, and vanilla panna cotta with a layer of membrane-free orange slices. The last two were exquisite. Note that the coffee fluff was served in ceramic containers cleverly designed to resemble slightly crushed disposable plastic coffee cups.

The two headwaiters were young women who clearly knew what they were doing. The two commis waiters were about 14 years old, first-season apprentices, and struggling a little—especially because so many of the dishes were served on slabs of slate (currently very much in vogue), which are very heavy and completely flat, very hard to set down and extract one's fingers without tipping. We saw one of them accidentally tip over one of the giant shrimp on the way to the table, trying to pick up the hot plate with a cloth, and the other knocked over one of our coffee fluffs setting it down, getting whipped cream on the table cloth. He seemed very apprehensive about our reaction, but we assured him it was fine, set the cup back upright (no harm done, as the fluff was too thick to spill), and moved the slate to cover the blot.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

First priority on Thursday was the Musée des Beaux Arts, in the ducal palace, but we stopped on the way to watch two guys in a high-reach cherrypicker working on the cleaning and restoration of the Church of St. Bénigne (of the 100 bell towers of Dijon, its is the highest, at 93 m—in my opinion, none of the towers is high enough; the ordinary buildings are so tall, and the streets so narrow, that it's hard to spot landmarks to orient yourself by). The photo on the left shows the contrast between the lower section, already cleaned, and the upper section, where the crane is working, which is still dark with lichen, smoke, and mildew. The close-up on the right shows the two guys chipping loose and removing a damaged collonette for restoration. They checked each collonette for stability, then removed any that were loose and seemed likely to fall, taking careful before-and-after pictures each time.

First priority on Thursday was the Musée des Beaux Arts, in the ducal palace, but we stopped on the way to watch two guys in a high-reach cherrypicker working on the cleaning and restoration of the Church of St. Bénigne (of the 100 bell towers of Dijon, its is the highest, at 93 m—in my opinion, none of the towers is high enough; the ordinary buildings are so tall, and the streets so narrow, that it's hard to spot landmarks to orient yourself by). The photo on the left shows the contrast between the lower section, already cleaned, and the upper section, where the crane is working, which is still dark with lichen, smoke, and mildew. The close-up on the right shows the two guys chipping loose and removing a damaged collonette for restoration. They checked each collonette for stability, then removed any that were loose and seemed likely to fall, taking careful before-and-after pictures each time.

That put us, right off the bat, in the "Salle de Garde," a magnificent hall with a fireplace I could stand up in, with a foot to spare, topped by magnificent flamboyant gothic stone carving. The ducal kitchen apparently has four fireplaces that big (although not as ornate), each large enough to burn cordwood and roast an entire ox. Besides a good deal of religious art, including several large alterpieces carved in high relief, the room houses the tombs of the first two of the "grand ducs"—Philipe le Hardi and Jean Sans Peur (and John's wife, Marguerite de Bavière, i.e., Margaret of Bavaria). Reclining effigies of the deceased rested, at about head height, lions crouching at their feet and angels hovering at their heads, on an elaborately carved base, and "elaborately carved" is an understatement. A procession of figures, first the clergy, then the rest of the ducal court, all dressed in mourning and weeping, runs all the way around each one, within a carved collonade. The figures are very white—I think they're made of marble or alabaster. You can see a little of one side below Philipe's head here, and below all of one side, in the photo of Margaret's reclining effigy. The tombs are the work of three successive sculptors who worked on them for years; the most famous was Klaus Sluter, from the Netherlands. His contribution to the arts of Dijon was so large that a statue of him, hammer and chisel in hand, stands in a courtyard of the palace.

That put us, right off the bat, in the "Salle de Garde," a magnificent hall with a fireplace I could stand up in, with a foot to spare, topped by magnificent flamboyant gothic stone carving. The ducal kitchen apparently has four fireplaces that big (although not as ornate), each large enough to burn cordwood and roast an entire ox. Besides a good deal of religious art, including several large alterpieces carved in high relief, the room houses the tombs of the first two of the "grand ducs"—Philipe le Hardi and Jean Sans Peur (and John's wife, Marguerite de Bavière, i.e., Margaret of Bavaria). Reclining effigies of the deceased rested, at about head height, lions crouching at their feet and angels hovering at their heads, on an elaborately carved base, and "elaborately carved" is an understatement. A procession of figures, first the clergy, then the rest of the ducal court, all dressed in mourning and weeping, runs all the way around each one, within a carved collonade. The figures are very white—I think they're made of marble or alabaster. You can see a little of one side below Philipe's head here, and below all of one side, in the photo of Margaret's reclining effigy. The tombs are the work of three successive sculptors who worked on them for years; the most famous was Klaus Sluter, from the Netherlands. His contribution to the arts of Dijon was so large that a statue of him, hammer and chisel in hand, stands in a courtyard of the palace.

Much of the museum's holdings consist of gruesome Medieval religious art, like this "Temptation of St. Anthony"

from a 14th century altarpiece by Jacques de Baerze. Anthony is beset by two ugly devils and a lovely young woman. At least he's not bleeding to death or being eaten alive like some of the others.

Much of the museum's holdings consist of gruesome Medieval religious art, like this "Temptation of St. Anthony"

from a 14th century altarpiece by Jacques de Baerze. Anthony is beset by two ugly devils and a lovely young woman. At least he's not bleeding to death or being eaten alive like some of the others.

After an hour or two in the museum, we turned in our audioguides, getting a little notation on our tickets so that we could pick them up again later without paying the fee again, and set off in search of lunch, which we found at the Brasserie du Théatre. I had a salad of confit duck gizzards and poached eggs (unusual in that the gizzards were left whole rather than sliced up and that the eggs were molded rather than free-form. David had the "salade gourmande." a gigantic conconction topped with toast, slabs of cold foie gras, two duck "sleeves" (i.e., "upper arms" of the wing, stewed to tenderness), a poached egg, and slices of duck-breast ham (you can see two of them, edged with white fat, between the egg and the leftmost tomato). (It was a bit much—great at the time, but on the way home from our equally huge dinner that night, David said, "Okay, bread and water tomorrow.")

After an hour or two in the museum, we turned in our audioguides, getting a little notation on our tickets so that we could pick them up again later without paying the fee again, and set off in search of lunch, which we found at the Brasserie du Théatre. I had a salad of confit duck gizzards and poached eggs (unusual in that the gizzards were left whole rather than sliced up and that the eggs were molded rather than free-form. David had the "salade gourmande." a gigantic conconction topped with toast, slabs of cold foie gras, two duck "sleeves" (i.e., "upper arms" of the wing, stewed to tenderness), a poached egg, and slices of duck-breast ham (you can see two of them, edged with white fat, between the egg and the leftmost tomato). (It was a bit much—great at the time, but on the way home from our equally huge dinner that night, David said, "Okay, bread and water tomorrow.")

Back at the museum, we finished off the rest of the area that was open. One highlight was a portrait by Nattier that, as usual, you could spot across the room as his work. The clothing and background were in darker colors than are typical of him, but the face was unmistakable. Nattier was in great demand as a portraitist because his works managed, simultaneously, to look just like the subject and to be extremely flattering. We have a poster of one in our livingroom that we got at the Jacquemart-André museum in Paris a few years ago. In the Egyptian room, I thought the most interesting item was this mummy of a cat. Finally a 19th century painting of the Salle des Gardes by Auguste Mathieu gives a better view of the room than we could manage. Apparently those works on the left-hand wall were never actually hung there; the artist just assembled his favorites from elsewhere in the museum and added them to his painting (I like that assortment a lot better than the grim altarpieces that do occupy that wall). Also, at present, the nearer tomb is oriented differently, with the angels at the far end rather than the near. Otherwise, that's pretty much what it looks like.

Back at the museum, we finished off the rest of the area that was open. One highlight was a portrait by Nattier that, as usual, you could spot across the room as his work. The clothing and background were in darker colors than are typical of him, but the face was unmistakable. Nattier was in great demand as a portraitist because his works managed, simultaneously, to look just like the subject and to be extremely flattering. We have a poster of one in our livingroom that we got at the Jacquemart-André museum in Paris a few years ago. In the Egyptian room, I thought the most interesting item was this mummy of a cat. Finally a 19th century painting of the Salle des Gardes by Auguste Mathieu gives a better view of the room than we could manage. Apparently those works on the left-hand wall were never actually hung there; the artist just assembled his favorites from elsewhere in the museum and added them to his painting (I like that assortment a lot better than the grim altarpieces that do occupy that wall). Also, at present, the nearer tomb is oriented differently, with the angels at the far end rather than the near. Otherwise, that's pretty much what it looks like.

On the way back to the hotel, we stopped in to have a look at the covered market. The timing never worked out for a visit while it was in operation—everything was closed down and the last of the clean-up was in progress when we were there—but its cast-iron architecture was worth a look. It has apparently not been altered since the market was built (in the Age of Eiffel).

On the way back to the hotel, we stopped in to have a look at the covered market. The timing never worked out for a visit while it was in operation—everything was closed down and the last of the clean-up was in progress when we were there—but its cast-iron architecture was worth a look. It has apparently not been altered since the market was built (in the Age of Eiffel). First course: An egg "cooked at low temperature"—to be precise, an egg cooked in the shell, in the oven, at exactly 61oC (= 141oF) for an hour—resting on a bed of braised sweet bell peppers, in turn resting on a bed of long-stewed tomatoes, topped with a crisp slice of pork belly, and surrounded by an emulsion of smoked bacon. Also, of course, the ubiquitous dots of balsamic vinegar syrup. The egg shimmied like the softest jelly, and as you can see, the white was almost transparent, but it was evenly congealed throughout, and the yolk was semiliquid and creamy. Excellent.

First course: An egg "cooked at low temperature"—to be precise, an egg cooked in the shell, in the oven, at exactly 61oC (= 141oF) for an hour—resting on a bed of braised sweet bell peppers, in turn resting on a bed of long-stewed tomatoes, topped with a crisp slice of pork belly, and surrounded by an emulsion of smoked bacon. Also, of course, the ubiquitous dots of balsamic vinegar syrup. The egg shimmied like the softest jelly, and as you can see, the white was almost transparent, but it was evenly congealed throughout, and the yolk was semiliquid and creamy. Excellent. Third course: A single gigantic Spanish shrimp described as "snackée" ("snacked," which I took to mean lightly smoked, like kippers), accompanied by artichoke purée, baby artichoke hearts in a light tomato sauce, a poached kumquat, a crisp sweetened lemon slice, and various purées and sauces of lemon and kumquat. Very good.

Third course: A single gigantic Spanish shrimp described as "snackée" ("snacked," which I took to mean lightly smoked, like kippers), accompanied by artichoke purée, baby artichoke hearts in a light tomato sauce, a poached kumquat, a crisp sweetened lemon slice, and various purées and sauces of lemon and kumquat. Very good. Fourth course: Sweetbreads braised, grilled, and buried under a shower of tiny spring vegetables and braised red onions, all surrounded by a lemon-ginger emulsion. Very good, but I've had better treatments of sweetbreads.

Fourth course: Sweetbreads braised, grilled, and buried under a shower of tiny spring vegetables and braised red onions, all surrounded by a lemon-ginger emulsion. Very good, but I've had better treatments of sweetbreads.

Seventh course, dessert and mignardises: The dessert was great. It consisted of a square of strawberry claffouti, vanilla ice cream, a strawberry tuile cookie, strawberry-fromage-blanc fluff, and a mixture of "fraises des bois" (French wild strawberries, picked that day from the wild by the chef) and gariguettes (my second-favorite variety of French domestic strawberries) sweetened with a light coating of strawberry syrup. Yum! The shiny comet-shaped object is a small blanched almond half dipped into sugar cooked to the molten-glass stage and pulled out to form a long, decorative tail.

Seventh course, dessert and mignardises: The dessert was great. It consisted of a square of strawberry claffouti, vanilla ice cream, a strawberry tuile cookie, strawberry-fromage-blanc fluff, and a mixture of "fraises des bois" (French wild strawberries, picked that day from the wild by the chef) and gariguettes (my second-favorite variety of French domestic strawberries) sweetened with a light coating of strawberry syrup. Yum! The shiny comet-shaped object is a small blanched almond half dipped into sugar cooked to the molten-glass stage and pulled out to form a long, decorative tail.