Saturday, 13 June 2009, Extra: Fromagerie Gaugry

Written 16 June 2009

The Fromagerie Gaugry is in Brochon (south of Dijon). I was a little puzzled by the diagrammatic map on their brochure, which showed the fromagerie as being between a giant "U" and something labeled "Florida," neither of which showed on our Michelin map, but David knew where it was (having spotted it as we drove by earlier on our way south, while I was looking the other way), so we found it without difficulty, right between a "Super-U" supermarket and a miniature-golf place called "Florida Park."

The Fromagerie Gaugry is in Brochon (south of Dijon). I was a little puzzled by the diagrammatic map on their brochure, which showed the fromagerie as being between a giant "U" and something labeled "Florida," neither of which showed on our Michelin map, but David knew where it was (having spotted it as we drove by earlier on our way south, while I was looking the other way), so we found it without difficulty, right between a "Super-U" supermarket and a miniature-golf place called "Florida Park."

It offers a fabulous self-guided tour, probably the best such tour of anything I've ever seen. You climb a flight of stairs from the parking lot to enter the building through a small door (out of sight to the right of the photo), then pass along a long, straight hallway, looking into the cheese-making areas through a series of large picture windows on one wall. On the other wall, and between the windows are large signboards, dense with information and very helpfully organized and illustrated, that explain the cheese-making process (both Gaugry's and in general); list many, many statistics; and answer every question you can think of! I photographed every last one of them, and it's great to have them to reread at leisure and to refer to when writing this blog, but I will restrain my urge just to post them all—for one thing, they're all in French. Along the way, you get to see this (apparently regionally famous) taxidermic composition illustrating La Fontaine's fable of the fox and the raven. The raven is holding a cheese (which the fox covets and tricks him into dropping) with the characteristic orange color of the soft-paste-washed-rind varieties.

Unfortunately, we were there on a Saturday afternoon, so not much was actually happening behind the windows, but all the apparatus was clearly visible, and a couple of guys were busily turning over the molds containing the most recently molded cheeses (so that they would drain evenly), so with the excellent signage, I felt we got an entirely comprehensive tour. If you want to the see more action behind the windows, though, it's best to show up on a weekday morning.

The milk (all cow's milk) comes from 30 suppliers, who keep three varieties of cows: Brune (a nice even brown with white rings around nose and eyes), Simmental (reddish brown and furrier, with a white face), and Montbéliarde (brown and white splotches).

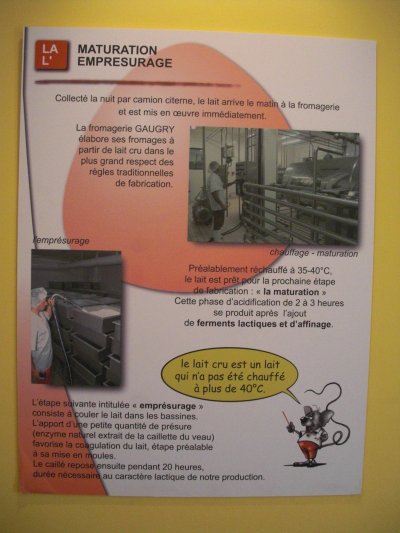

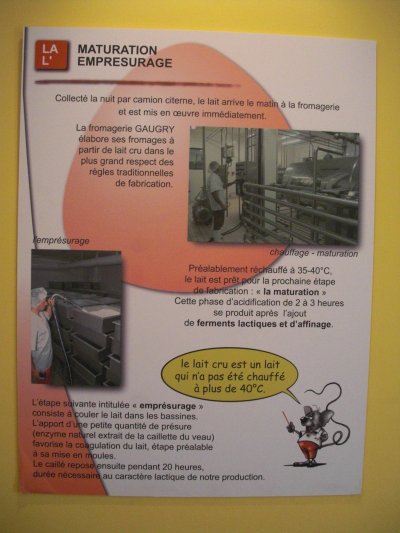

They use about 9000 liters of milk a day (i.e., 1,700,000 liters a year) to make, each year, about 700,000 individual cheeses, all cylindrical and mostly the size and shape of a Camembert (a standard cheese-mold size) but some larger or smaller. Of that production, 55% goes to French wholesalers, 21% to export wholesalers, 19% to retailers, and 5% directly to restaurants. The milk is never heated above 40°C, so their cheeses can be advertised as "raw milk."

The milk shows up at the factory first thing in the morning, in tank trucks, and goes straight into production. It is first heated gently to between 35 and 40°C and allowed to acidify (with the aid of bacteria) for 2-3 hours. It is then mixed with a small amount of rennet (an enzyme from calf stomachs), poured into metal trays ( couple of feet square and maybe eight inches deep), and left to coagulate and rest for 20 hours (all at controlled temperature and humidity, of course). Up to this point, the procedure is basically the same as that for the ladle-molded goat cheeses at Sweet Grass Dairy ((our wonderful local cheesemakers in Thomasville, GA). Next, at Sweet Grass Dairy, the curds are gently ladled into individual molds and left to drain, but Gaugry's run on a much larger scale. Instead, they push a short of cross-hatched cookie-cutter into each tray to cut the curd into large blocks. Then, they place a plastic apparatus on top that functions as a sort of multiple funnel—on the side toward the curd, it's divided into rectangles that cover the whole surface of the ray, but on the upper side, it has narrowed to a 5 by 4 array of round openings. On top of that goes a rack of cylindrical cheese-molds, 20 of them all linked together into a unit, that line up with those round openings. This assembly is placed on the machine at the right, which turns the whole thing upside down, neatly sliding the evenly divided contents of the tray into the 20 molds, which are then taken to the room next door and left on racks to drain. This process is repeated for each tray (9000 liters' worth per day).

The milk shows up at the factory first thing in the morning, in tank trucks, and goes straight into production. It is first heated gently to between 35 and 40°C and allowed to acidify (with the aid of bacteria) for 2-3 hours. It is then mixed with a small amount of rennet (an enzyme from calf stomachs), poured into metal trays ( couple of feet square and maybe eight inches deep), and left to coagulate and rest for 20 hours (all at controlled temperature and humidity, of course). Up to this point, the procedure is basically the same as that for the ladle-molded goat cheeses at Sweet Grass Dairy ((our wonderful local cheesemakers in Thomasville, GA). Next, at Sweet Grass Dairy, the curds are gently ladled into individual molds and left to drain, but Gaugry's run on a much larger scale. Instead, they push a short of cross-hatched cookie-cutter into each tray to cut the curd into large blocks. Then, they place a plastic apparatus on top that functions as a sort of multiple funnel—on the side toward the curd, it's divided into rectangles that cover the whole surface of the ray, but on the upper side, it has narrowed to a 5 by 4 array of round openings. On top of that goes a rack of cylindrical cheese-molds, 20 of them all linked together into a unit, that line up with those round openings. This assembly is placed on the machine at the right, which turns the whole thing upside down, neatly sliding the evenly divided contents of the tray into the 20 molds, which are then taken to the room next door and left on racks to drain. This process is repeated for each tray (9000 liters' worth per day).

In the first day after being molded, during which they are inverted twice by hand (the only operation we actually got to witness), the cheeses lose about 80% of their liquid content. Two days after that, they are firm enough to be unmolded and are transferred to wire racks and placed in a cool room to firm up a little and dry their surfaces (a process called "ressuyage").

In the first day after being molded, during which they are inverted twice by hand (the only operation we actually got to witness), the cheeses lose about 80% of their liquid content. Two days after that, they are firm enough to be unmolded and are transferred to wire racks and placed in a cool room to firm up a little and dry their surfaces (a process called "ressuyage").

Next, the cheeses get their "dry salting"—they are passed through a blower-driven snowstorm of very fine salt, getting a coating that adds 1.5 to 2% to their weight. The salt serves the triple purpose of helping to preserve the cheese, promoting its aging process, and improving its taste. It remains salted in this way for 2-3 days.

On the eighth day after molding, each cheese is hand washed with a salt solution (spiked with, if the cheese variety calls for it, either Chablis wine or marc de Bourgogne, a fierce brandy made from the grape seeds and skins left over from wine making). The washing step is repeated seven or eight times during the aging process (which lasts at least four weeks and longer for some varieties). The orange color develops naturally—as the cartoon mouse who inhabits the margins of the signboards tells us, Gaugry uses no coloring agents.

Here are two views into the aging room, at cheeses at different stages of the process. The younger cheeses at the left are still pale and relatively smooth. The older ones at the right have taken on their orange color, and their skins have shrivelled as they lost more moisture with age.

Here are two views into the aging room, at cheeses at different stages of the process. The younger cheeses at the left are still pale and relatively smooth. The older ones at the right have taken on their orange color, and their skins have shrivelled as they lost more moisture with age.

Gaugry makes just one of the eight styles of French cheese—"pâtes molles à croûte lavée" ("soft paste with washed rind"). That is, the cheese curds are neither heated nor pressed, and the cheeses, once drained and firm enough, are washed regularly while they mature, so they end of up with a soft, smooth, orangy-colored, edible rind (not, e.g., a tough rind like Gruyère or a white, downy rind like Brie). As far as I know, Sweet Grass Dairy doesn't make anything in that style (Wehners and Littles all, please correct me if I'm wrong).

Within that style, they make seven varieties (different subsets of which are shown in these posters hung in the tasting-room window; no tastings on Saturday, alas, but the shop was open), all variations on Époisses that differ from it in their treatment during aging—some are washed in brandy rather than salt water, some coated with ash, etc. : époisses (their most classic cheese and flagship variety), l'Ami du Chambertin (washed with marc de Bourgogne; it was invented around 1950 at Gaugry), Plaisir du Chablis (washed weekly with Chablis wine), Palet de Bourgogne (also invented at Gaugry), Petit Creux (with a little hollow on top that you fill with marc de Bourgogne; you eat the cheese when it has soaked up all the liquor); Soumantrain, Cendré de Vergy (a gray, ash-covered variety). I don't know, but I suspect they just refrain from turning Petit Creux while it drains, so that it sinks down in the center rather than settling into a disk of even thickness.

Within that style, they make seven varieties (different subsets of which are shown in these posters hung in the tasting-room window; no tastings on Saturday, alas, but the shop was open), all variations on Époisses that differ from it in their treatment during aging—some are washed in brandy rather than salt water, some coated with ash, etc. : époisses (their most classic cheese and flagship variety), l'Ami du Chambertin (washed with marc de Bourgogne; it was invented around 1950 at Gaugry), Plaisir du Chablis (washed weekly with Chablis wine), Palet de Bourgogne (also invented at Gaugry), Petit Creux (with a little hollow on top that you fill with marc de Bourgogne; you eat the cheese when it has soaked up all the liquor); Soumantrain, Cendré de Vergy (a gray, ash-covered variety). I don't know, but I suspect they just refrain from turning Petit Creux while it drains, so that it sinks down in the center rather than settling into a disk of even thickness.

Each variety has a catch-phrase used in its advertising—like "The strength and finesse of l'Ami du Chambertin," "The intimacy of the Palet de Bourgogne," "The country atmosphere of the Cendré de Vergy." Between them, l'Ami du Chambertin and Époisses make up over 70% of Gaugry's production by weight (the Cendrée and a few fresh cheeses make up about 1% each. Many different companies make Époisses and variations on it, but it can only be called by that name if all the milk comes from certified farms within, and the cheese is made within, the officially designated Époisses region. When ready to eat, Époisses is pretty much liquid, so it is traditionally served right from its little balsawood box, sometimes with a spoon. This collection of old boxes was hung on the wall in a picture frame.

Each variety has a catch-phrase used in its advertising—like "The strength and finesse of l'Ami du Chambertin," "The intimacy of the Palet de Bourgogne," "The country atmosphere of the Cendré de Vergy." Between them, l'Ami du Chambertin and Époisses make up over 70% of Gaugry's production by weight (the Cendrée and a few fresh cheeses make up about 1% each. Many different companies make Époisses and variations on it, but it can only be called by that name if all the milk comes from certified farms within, and the cheese is made within, the officially designated Époisses region. When ready to eat, Époisses is pretty much liquid, so it is traditionally served right from its little balsawood box, sometimes with a spoon. This collection of old boxes was hung on the wall in a picture frame.

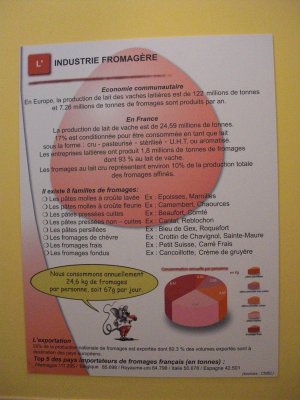

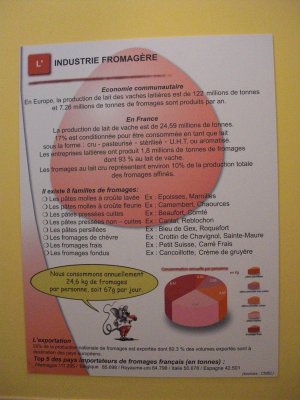

This poster about the cheese industry lists the eight types of French cheese, which are (besides the soft paste washed rind), soft paste "flowered" rind (like Camembert, Brie, and Chource), pressed cooked paste (like Beaufort and Comté; not really cooked, but the curds are heated to make them firmer before they are molded), pressed uncooked paste (like Cantal and Reblochon), "parslied" paste (the blues, like Roquefort and Fourme d'Ambert), chevres (goat cheeses, like Crottin de Chavignol, Sainte -Maure, and Rocadamour; goat's milk is sometimes also used in the other varieties), fresh cheeses (like Petit Suisse; cottage cheese and cream cheese would fall in this category, if they French used them), and processed cheeses (like Vache qui rit and Boulette d'Avesne). According to the little mouse, the French eat, on average 24.6 kilos of cheese per person per year, or about 67 g per day.

All this draining and washing of cheeses produces a lot of potentially polluting fluids, but Gaugry was one of the first enterprises in the world to set up a "methanization" operation. All the whey and washing fluid is pumped into a reactor where bacteria eat up the pollutants (and I assume the salt is extracted in some fashion), producing in the process large amounts of "biogas," mostly methane, which is in turn burned to power the factory. A cubic meter of "lactoserum" (drained from cheese) can produce methane equivalent to 25 liters of fuel oil! The Gaugry factory saves about 100-190 liters of fossil fuel a day by burning the gas it produces in the process of purifying its effluents to the point where the municipal water-treatment plant can take over.

Near the end of the tour was a small museum of antique cheese-making and other dairy equipment. that included two styles of cutters (used to cut the solid block of curd into smaller pieces before it is either "cooked" or placed directly in molds). Behind, and a little hard to see, is a shaft with a small wooden bow across the top and a metal cross piece lower down, between which are strung wires. In the front is one designed to work like a giant whisk (it stood about three feet tall).

Near the end of the tour was a small museum of antique cheese-making and other dairy equipment. that included two styles of cutters (used to cut the solid block of curd into smaller pieces before it is either "cooked" or placed directly in molds). Behind, and a little hard to see, is a shaft with a small wooden bow across the top and a metal cross piece lower down, between which are strung wires. In the front is one designed to work like a giant whisk (it stood about three feet tall).

The wooden, birdbath-shaped apparatus is a "malaxeur," used to knead freshly churned butter to mix in salt and to get rid of any large bubbles of whey in it. Turning the crank both turned the knurled rolling-pin and rotated the ridged platter.

The shop was great, but we resisted all temptation to buy—we had reservations for major dinners every single night and had no appetite to spare for random munchies, and the USDA would have hysterics if we tried to bring any of this stuff home. In addition to Gaugry's own cheeses, they were selling varieties from all over France, as well as little peasant dolls, wines, beers, black-currant products, gingerbread, and candies.

In this photo, the row of bags contains various common and exotic flours—wheat, rye, buckwheat, spelt, chestnut— and lentils. The brown wedge behind the cutting board is sliced-to-order pain d'épices, and the sign next to it advertises isothermal bags for your cheese for the drive home (you can see one hanging below the scale), with ice thrown in free. In the photo at the right are a selection of goat cheeses, including little "barrattes" ("churns," because of the shape), each about two bites' worth.

In this photo, the row of bags contains various common and exotic flours—wheat, rye, buckwheat, spelt, chestnut— and lentils. The brown wedge behind the cutting board is sliced-to-order pain d'épices, and the sign next to it advertises isothermal bags for your cheese for the drive home (you can see one hanging below the scale), with ice thrown in free. In the photo at the right are a selection of goat cheeses, including little "barrattes" ("churns," because of the shape), each about two bites' worth.

On the left, a basket piled with Saint-Marcellin cheeses (I've never seen them stacked free-standing like this; they're usually sold and served each in its own little ceramic dish, designed to keep the cheese from making a break for it), and on the right a stack of vacuum packs of jambon persillé, these specifically labeled as being from the town of Marsannay, which must have its own distinct style. You could put together a really serious picnic in that shop!

On the left, a basket piled with Saint-Marcellin cheeses (I've never seen them stacked free-standing like this; they're usually sold and served each in its own little ceramic dish, designed to keep the cheese from making a break for it), and on the right a stack of vacuum packs of jambon persillé, these specifically labeled as being from the town of Marsannay, which must have its own distinct style. You could put together a really serious picnic in that shop!

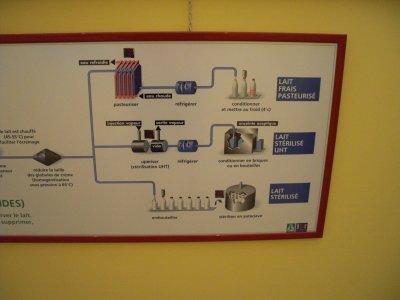

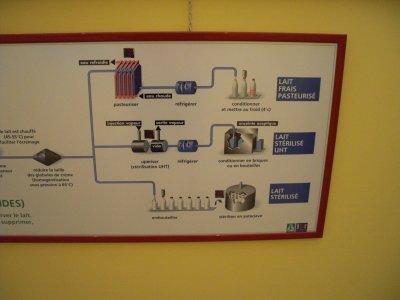

Finally, here what I consider some of the most informative signboards on the tour. Each was so wide that I had to photograph it in two pieces. This first pair shows the "flow chart" of the processing of liquid milk, from milking at the upper left corner through the steps leading to bottled raw milk ("lait cru") in the left-hand photo, then through homogenization, pasteurization, and other steps leading to ordinary pasteurized milk, UHT milk, and truly sterilized milk (at the right-hand end of the right-hand photo).

Finally, here what I consider some of the most informative signboards on the tour. Each was so wide that I had to photograph it in two pieces. This first pair shows the "flow chart" of the processing of liquid milk, from milking at the upper left corner through the steps leading to bottled raw milk ("lait cru") in the left-hand photo, then through homogenization, pasteurization, and other steps leading to ordinary pasteurized milk, UHT milk, and truly sterilized milk (at the right-hand end of the right-hand photo).

Finally, these tow photos show the steps from milking (again at the upper left in the left-hand photo) through all the various steps in cheesemaking to produce six of the eight types (chevre and fresh cheese are left out). The soft-paste-washed-rind cheese of Gaugry are second from the top at the far right, the characteristically orange-colored ones.

Finally, these tow photos show the steps from milking (again at the upper left in the left-hand photo) through all the various steps in cheesemaking to produce six of the eight types (chevre and fresh cheese are left out). The soft-paste-washed-rind cheese of Gaugry are second from the top at the far right, the characteristically orange-colored ones.

In short, if you ever get a chance to visit this place, don't miss it! I really do have full-size, legible photos of all the posters and more views in through the windows, so if you'd like to see more, do let me know.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

The Fromagerie Gaugry is in Brochon (south of Dijon). I was a little puzzled by the diagrammatic map on their brochure, which showed the fromagerie as being between a giant "U" and something labeled "Florida," neither of which showed on our Michelin map, but David knew where it was (having spotted it as we drove by earlier on our way south, while I was looking the other way), so we found it without difficulty, right between a "Super-U" supermarket and a miniature-golf place called "Florida Park."

The Fromagerie Gaugry is in Brochon (south of Dijon). I was a little puzzled by the diagrammatic map on their brochure, which showed the fromagerie as being between a giant "U" and something labeled "Florida," neither of which showed on our Michelin map, but David knew where it was (having spotted it as we drove by earlier on our way south, while I was looking the other way), so we found it without difficulty, right between a "Super-U" supermarket and a miniature-golf place called "Florida Park."

The milk shows up at the factory first thing in the morning, in tank trucks, and goes straight into production. It is first heated gently to between 35 and 40°C and allowed to acidify (with the aid of bacteria) for 2-3 hours. It is then mixed with a small amount of rennet (an enzyme from calf stomachs), poured into metal trays ( couple of feet square and maybe eight inches deep), and left to coagulate and rest for 20 hours (all at controlled temperature and humidity, of course). Up to this point, the procedure is basically the same as that for the ladle-molded goat cheeses at Sweet Grass Dairy ((our wonderful local cheesemakers in Thomasville, GA). Next, at Sweet Grass Dairy, the curds are gently ladled into individual molds and left to drain, but Gaugry's run on a much larger scale. Instead, they push a short of cross-hatched cookie-cutter into each tray to cut the curd into large blocks. Then, they place a plastic apparatus on top that functions as a sort of multiple funnel—on the side toward the curd, it's divided into rectangles that cover the whole surface of the ray, but on the upper side, it has narrowed to a 5 by 4 array of round openings. On top of that goes a rack of cylindrical cheese-molds, 20 of them all linked together into a unit, that line up with those round openings. This assembly is placed on the machine at the right, which turns the whole thing upside down, neatly sliding the evenly divided contents of the tray into the 20 molds, which are then taken to the room next door and left on racks to drain. This process is repeated for each tray (9000 liters' worth per day).

The milk shows up at the factory first thing in the morning, in tank trucks, and goes straight into production. It is first heated gently to between 35 and 40°C and allowed to acidify (with the aid of bacteria) for 2-3 hours. It is then mixed with a small amount of rennet (an enzyme from calf stomachs), poured into metal trays ( couple of feet square and maybe eight inches deep), and left to coagulate and rest for 20 hours (all at controlled temperature and humidity, of course). Up to this point, the procedure is basically the same as that for the ladle-molded goat cheeses at Sweet Grass Dairy ((our wonderful local cheesemakers in Thomasville, GA). Next, at Sweet Grass Dairy, the curds are gently ladled into individual molds and left to drain, but Gaugry's run on a much larger scale. Instead, they push a short of cross-hatched cookie-cutter into each tray to cut the curd into large blocks. Then, they place a plastic apparatus on top that functions as a sort of multiple funnel—on the side toward the curd, it's divided into rectangles that cover the whole surface of the ray, but on the upper side, it has narrowed to a 5 by 4 array of round openings. On top of that goes a rack of cylindrical cheese-molds, 20 of them all linked together into a unit, that line up with those round openings. This assembly is placed on the machine at the right, which turns the whole thing upside down, neatly sliding the evenly divided contents of the tray into the 20 molds, which are then taken to the room next door and left on racks to drain. This process is repeated for each tray (9000 liters' worth per day).

In the first day after being molded, during which they are inverted twice by hand (the only operation we actually got to witness), the cheeses lose about 80% of their liquid content. Two days after that, they are firm enough to be unmolded and are transferred to wire racks and placed in a cool room to firm up a little and dry their surfaces (a process called "ressuyage").

In the first day after being molded, during which they are inverted twice by hand (the only operation we actually got to witness), the cheeses lose about 80% of their liquid content. Two days after that, they are firm enough to be unmolded and are transferred to wire racks and placed in a cool room to firm up a little and dry their surfaces (a process called "ressuyage").

Here are two views into the aging room, at cheeses at different stages of the process. The younger cheeses at the left are still pale and relatively smooth. The older ones at the right have taken on their orange color, and their skins have shrivelled as they lost more moisture with age.

Here are two views into the aging room, at cheeses at different stages of the process. The younger cheeses at the left are still pale and relatively smooth. The older ones at the right have taken on their orange color, and their skins have shrivelled as they lost more moisture with age.

Within that style, they make seven varieties (different subsets of which are shown in these posters hung in the tasting-room window; no tastings on Saturday, alas, but the shop was open), all variations on Époisses that differ from it in their treatment during aging—some are washed in brandy rather than salt water, some coated with ash, etc. : époisses (their most classic cheese and flagship variety), l'Ami du Chambertin (washed with marc de Bourgogne; it was invented around 1950 at Gaugry), Plaisir du Chablis (washed weekly with Chablis wine), Palet de Bourgogne (also invented at Gaugry), Petit Creux (with a little hollow on top that you fill with marc de Bourgogne; you eat the cheese when it has soaked up all the liquor); Soumantrain, Cendré de Vergy (a gray, ash-covered variety). I don't know, but I suspect they just refrain from turning Petit Creux while it drains, so that it sinks down in the center rather than settling into a disk of even thickness.

Within that style, they make seven varieties (different subsets of which are shown in these posters hung in the tasting-room window; no tastings on Saturday, alas, but the shop was open), all variations on Époisses that differ from it in their treatment during aging—some are washed in brandy rather than salt water, some coated with ash, etc. : époisses (their most classic cheese and flagship variety), l'Ami du Chambertin (washed with marc de Bourgogne; it was invented around 1950 at Gaugry), Plaisir du Chablis (washed weekly with Chablis wine), Palet de Bourgogne (also invented at Gaugry), Petit Creux (with a little hollow on top that you fill with marc de Bourgogne; you eat the cheese when it has soaked up all the liquor); Soumantrain, Cendré de Vergy (a gray, ash-covered variety). I don't know, but I suspect they just refrain from turning Petit Creux while it drains, so that it sinks down in the center rather than settling into a disk of even thickness.

Each variety has a catch-phrase used in its advertising—like "The strength and finesse of l'Ami du Chambertin," "The intimacy of the Palet de Bourgogne," "The country atmosphere of the Cendré de Vergy." Between them, l'Ami du Chambertin and Époisses make up over 70% of Gaugry's production by weight (the Cendrée and a few fresh cheeses make up about 1% each. Many different companies make Époisses and variations on it, but it can only be called by that name if all the milk comes from certified farms within, and the cheese is made within, the officially designated Époisses region. When ready to eat, Époisses is pretty much liquid, so it is traditionally served right from its little balsawood box, sometimes with a spoon. This collection of old boxes was hung on the wall in a picture frame.

Each variety has a catch-phrase used in its advertising—like "The strength and finesse of l'Ami du Chambertin," "The intimacy of the Palet de Bourgogne," "The country atmosphere of the Cendré de Vergy." Between them, l'Ami du Chambertin and Époisses make up over 70% of Gaugry's production by weight (the Cendrée and a few fresh cheeses make up about 1% each. Many different companies make Époisses and variations on it, but it can only be called by that name if all the milk comes from certified farms within, and the cheese is made within, the officially designated Époisses region. When ready to eat, Époisses is pretty much liquid, so it is traditionally served right from its little balsawood box, sometimes with a spoon. This collection of old boxes was hung on the wall in a picture frame.

Near the end of the tour was a small museum of antique cheese-making and other dairy equipment. that included two styles of cutters (used to cut the solid block of curd into smaller pieces before it is either "cooked" or placed directly in molds). Behind, and a little hard to see, is a shaft with a small wooden bow across the top and a metal cross piece lower down, between which are strung wires. In the front is one designed to work like a giant whisk (it stood about three feet tall).

Near the end of the tour was a small museum of antique cheese-making and other dairy equipment. that included two styles of cutters (used to cut the solid block of curd into smaller pieces before it is either "cooked" or placed directly in molds). Behind, and a little hard to see, is a shaft with a small wooden bow across the top and a metal cross piece lower down, between which are strung wires. In the front is one designed to work like a giant whisk (it stood about three feet tall).

In this photo, the row of bags contains various common and exotic flours—wheat, rye, buckwheat, spelt, chestnut— and lentils. The brown wedge behind the cutting board is sliced-to-order pain d'épices, and the sign next to it advertises isothermal bags for your cheese for the drive home (you can see one hanging below the scale), with ice thrown in free. In the photo at the right are a selection of goat cheeses, including little "barrattes" ("churns," because of the shape), each about two bites' worth.

In this photo, the row of bags contains various common and exotic flours—wheat, rye, buckwheat, spelt, chestnut— and lentils. The brown wedge behind the cutting board is sliced-to-order pain d'épices, and the sign next to it advertises isothermal bags for your cheese for the drive home (you can see one hanging below the scale), with ice thrown in free. In the photo at the right are a selection of goat cheeses, including little "barrattes" ("churns," because of the shape), each about two bites' worth.

On the left, a basket piled with Saint-Marcellin cheeses (I've never seen them stacked free-standing like this; they're usually sold and served each in its own little ceramic dish, designed to keep the cheese from making a break for it), and on the right a stack of vacuum packs of jambon persillé, these specifically labeled as being from the town of Marsannay, which must have its own distinct style. You could put together a really serious picnic in that shop!

On the left, a basket piled with Saint-Marcellin cheeses (I've never seen them stacked free-standing like this; they're usually sold and served each in its own little ceramic dish, designed to keep the cheese from making a break for it), and on the right a stack of vacuum packs of jambon persillé, these specifically labeled as being from the town of Marsannay, which must have its own distinct style. You could put together a really serious picnic in that shop!

Finally, here what I consider some of the most informative signboards on the tour. Each was so wide that I had to photograph it in two pieces. This first pair shows the "flow chart" of the processing of liquid milk, from milking at the upper left corner through the steps leading to bottled raw milk ("lait cru") in the left-hand photo, then through homogenization, pasteurization, and other steps leading to ordinary pasteurized milk, UHT milk, and truly sterilized milk (at the right-hand end of the right-hand photo).

Finally, here what I consider some of the most informative signboards on the tour. Each was so wide that I had to photograph it in two pieces. This first pair shows the "flow chart" of the processing of liquid milk, from milking at the upper left corner through the steps leading to bottled raw milk ("lait cru") in the left-hand photo, then through homogenization, pasteurization, and other steps leading to ordinary pasteurized milk, UHT milk, and truly sterilized milk (at the right-hand end of the right-hand photo).

Finally, these tow photos show the steps from milking (again at the upper left in the left-hand photo) through all the various steps in cheesemaking to produce six of the eight types (chevre and fresh cheese are left out). The soft-paste-washed-rind cheese of Gaugry are second from the top at the far right, the characteristically orange-colored ones.

Finally, these tow photos show the steps from milking (again at the upper left in the left-hand photo) through all the various steps in cheesemaking to produce six of the eight types (chevre and fresh cheese are left out). The soft-paste-washed-rind cheese of Gaugry are second from the top at the far right, the characteristically orange-colored ones.