Monday, 26 July 2010: Bastogne to Waterloo (yet a different war)

Written 23 August 2010

The next morning, the door to the "breakfast room" proved to open into a sunny, expansive (and deserted) dining room with mirrors and cherry paneling. Here, I'm taking a photo of myself and David (and, in the background, the breakfast buffet) in one of the mirrors. A peek down the stairs at the far end of the room revealed that we were in the upstairs portion of the a large and handsome bar, across the street from Wagon Leo, which we'd walked past the previous evening. It didn't say "Leo" on it anywhere, but I suspect it's under the same management. Every now and then, someone would come up from downstairs to check the buffet, but otherwise, we had the place to ourselves.

The next morning, the door to the "breakfast room" proved to open into a sunny, expansive (and deserted) dining room with mirrors and cherry paneling. Here, I'm taking a photo of myself and David (and, in the background, the breakfast buffet) in one of the mirrors. A peek down the stairs at the far end of the room revealed that we were in the upstairs portion of the a large and handsome bar, across the street from Wagon Leo, which we'd walked past the previous evening. It didn't say "Leo" on it anywhere, but I suspect it's under the same management. Every now and then, someone would come up from downstairs to check the buffet, but otherwise, we had the place to ourselves.

The buffet managed to make a virtue of the waste-not-want-not economy of the Leo establishments. Right there with the rest of the breakfast things—small fridge full of yogurt; platters of ham, cheese, salami, salmon; fruit salad; jam; several breads and pastries—were two silver ice buckets, one full of cartons of orange and other fruit juices and the other containing a bottle of champagne! When you think about it, the Leo empire includes several easteries, all of which sell champagne by the glass, so they're bound to have a half bottle or two left over daily. What better use for it than to add a sense of luxury to breakfast?! David had a mimosa just because he could.

We set off pretty promptly after breakfast, so as to maximize our time in Waterloo, where once again, we'd only have one night. We studied the map and debated making a northward detour to visit the area where David's uncle served during WWII but decided we wouldn't have time.

Leaving the flattish area around Bastogne, we ran first into first rolling hills and then into more of the steep heavily forested ridges of the Ardennes. Judging from restaurant menus, ham is definitely a specialty of the Bastogne area, but as usual, we saw no pigs anywhere. Around Namur, we encountered a lot of dairy farming. We also passed a number of public-service billboards that it took me a while to parse. One had a photo of a smiling woman, lying in a mass of shattered glass next to a cell phone with a text message reading "Loulou pq t'a raccroché?" (Loulou, why'd you hang up?) Another, showing a wallet photo of a little girl, also behind shattered glass, was captioned, "Papa, on a été coupé!" (Papa, we've been cut off!). Across each one was "Pas de GSM au volant!" (No GSM at the wheel!). I finally realized that "GSM" is Belgian French for cell phone. After Namur, we saw the first colza of the trip, as well as potatoes, sugar beets, and grain in large, fairly flat fields.

Waterloo is a fairly small town, now mostly a bedroom community for nearby Brussels. We drove into town from the south on the very road Napoleon was marching along when he got there, and when we came to the crossroads he hoped to capture, we were pretty much on the battlefield. We drove past the farm where he set up his headquarters, now a museum, and we could plainly see, from the main road, the "Butte du Lion" (the Lion Mound), the conical artifical hill that now marks the place where the fighting was thickest—actually, it marks the spot where the crown prince of the Netherlands (of which Belgium was then part) was wounded during the battle, but it comes to the same thing.

Waterloo is a fairly small town, now mostly a bedroom community for nearby Brussels. We drove into town from the south on the very road Napoleon was marching along when he got there, and when we came to the crossroads he hoped to capture, we were pretty much on the battlefield. We drove past the farm where he set up his headquarters, now a museum, and we could plainly see, from the main road, the "Butte du Lion" (the Lion Mound), the conical artifical hill that now marks the place where the fighting was thickest—actually, it marks the spot where the crown prince of the Netherlands (of which Belgium was then part) was wounded during the battle, but it comes to the same thing.

We continued on into town and, on our way to our hotel, still on that same north-south road, we passed the tourist information office and, right across the street from it, Wellington's headquarters, also now a museum. The entrance to our hotel, Le Cot&eactue; Vert, was only a block further along and looked like an alley, but a few yards off the road, it broadened out into an attractive paved, tree-shaded courtyard in front of beautilfully landscaped sloping lawns and the hotel itself. One of the trees was laden with small but tasty ripe cherries.

Our room was comfortable and spacious and already furnished with two four-foot-tall oscillating fans. I peered out our window, about three blocks beyond which (my maps told me) was another snail farm, but I couldn't see it. I resisted the temptation to go take a closer look. According to their website, the snail farmers would be off at a market somewhere that day, anyway.

The next order of business was lunch, so we asked for advice at the reception desk. The clerk listed a half-dozen nearby restaurants, but the minute she mentioned Le Pain Quotidien, the choice was made. That's the great bakery where we had two excellent breakfasts in Ghent, and now we got to try its lunch selections. A whole section of the menu was dedicated to "tartines" (bread spread with something) and another to salads. I ordered the tartine of roast beef, mustard, capers and arugula; David had the salad of warm goat cheese with sirop de Liège, apples, raisins and granola. Both delicious. Wish we had a bakery like that around here!

The next order of business was lunch, so we asked for advice at the reception desk. The clerk listed a half-dozen nearby restaurants, but the minute she mentioned Le Pain Quotidien, the choice was made. That's the great bakery where we had two excellent breakfasts in Ghent, and now we got to try its lunch selections. A whole section of the menu was dedicated to "tartines" (bread spread with something) and another to salads. I ordered the tartine of roast beef, mustard, capers and arugula; David had the salad of warm goat cheese with sirop de Liège, apples, raisins and granola. Both delicious. Wish we had a bakery like that around here!

Next, a visit to the tourist office, to plan our campaign. For once, it looked as though we would be able to "see everything," that is, visit all the major attractions relevant to the battle of Waterloo—the Butte du Lion and its museum, the adjacent circular panoramic painting in its round building, the cross-country battlefield tour in four-wheel drive trucks, Napoleon's headquarters, the local church (full of Waterloo memorials), and Wellington's headquarters—in the time allotted, so we bought combined "everything" tickets. Only the church and Wellington's headquarters were within walking distance, so we saved those for last and set of by car for the butte.

Our admission tickets to the butte's museum also included the chance to climb the butte itself and a few outdoor exhibits, like this Napoleonic-era horse-drawn field forge. The blacksmith presumably set up his anvil (stored in the chest over the large rear wheels?) on the ground and built his fire in the iron section of the wagon, fanning it with the large bellows (itself protected from the heat by the iron screen between it and the fire. Behind the forge inthe photo is a period horse-drawn field ambulance. I also got this photo of one of the three trucks used for the battle-field tour, but if you'll look closely at its front tire, you'll see why the tours were not running that day—flat as the proverbial pancake. All the trucks had the same trouble, which the folks at the museum cashier's desk attributed to vandals.

Our admission tickets to the butte's museum also included the chance to climb the butte itself and a few outdoor exhibits, like this Napoleonic-era horse-drawn field forge. The blacksmith presumably set up his anvil (stored in the chest over the large rear wheels?) on the ground and built his fire in the iron section of the wagon, fanning it with the large bellows (itself protected from the heat by the iron screen between it and the fire. Behind the forge inthe photo is a period horse-drawn field ambulance. I also got this photo of one of the three trucks used for the battle-field tour, but if you'll look closely at its front tire, you'll see why the tours were not running that day—flat as the proverbial pancake. All the trucks had the same trouble, which the folks at the museum cashier's desk attributed to vandals.

The museum visit started with two films, one an "informational" film with a narrator in modern dress who walked around among costumed actors recreating parts of the battle and the other an actual dramatization of the battle (shortened from a feature-length film). It was apparently French-made—historians have long said it was a mistake on Napoleon's to leave the battlefield and head for the coast as soon as it was clear the battle was lost, but in this film, he was portrayed as being dragged away, struggling and shouting that he would never desert his troops, by his officers who insisted, "But you must leave, sir; France needs you!" Among other exhibits in the museum was an entire room devoted to places around the world that were named "Waterloo" in commemoration of hte battle.

At first, we looked at the long straight staircase up the side of the butte and decided it wasn't worth it, but once we realized we might not get to go on the truck tour, we climbed it anyway, for the view of the terrain. For an idea of the scale of the lion and its pedestal, compare it with the people climbing the stairs and the ones at the top, sillouetted against the sky below and to the right of the monument. The butte built shortly after the battle, and when Wellington first saw it, he is said to have exclaimed, "They've spoiled my battlefield!" The view was great. At the top, I listened in amusement for some time to a pair of teenage American boys who were discoursing quite knowledgeably to their parents on the history behind and strategy during the battle and were being very patient, I thought, with the parents' lack of comprehension and/or interest—a definite reversal of the roles you usually see on family trips! The photo at the right shows the museum we had just toured (the rectangular buildings at the right with the three disabled trucks parked next to them) and the round building that houses the 1912 panoramic painting.

At first, we looked at the long straight staircase up the side of the butte and decided it wasn't worth it, but once we realized we might not get to go on the truck tour, we climbed it anyway, for the view of the terrain. For an idea of the scale of the lion and its pedestal, compare it with the people climbing the stairs and the ones at the top, sillouetted against the sky below and to the right of the monument. The butte built shortly after the battle, and when Wellington first saw it, he is said to have exclaimed, "They've spoiled my battlefield!" The view was great. At the top, I listened in amusement for some time to a pair of teenage American boys who were discoursing quite knowledgeably to their parents on the history behind and strategy during the battle and were being very patient, I thought, with the parents' lack of comprehension and/or interest—a definite reversal of the roles you usually see on family trips! The photo at the right shows the museum we had just toured (the rectangular buildings at the right with the three disabled trucks parked next to them) and the round building that houses the 1912 panoramic painting.

Written 25 August 2010

Apparently, several circular panoramic paintings of the battle were made—one, since destroyed, was displayed in London as early as 1815, the year the battle was fought—but the one at Waterloo is the only one that survives. It's showing some obvious roof-leak damage, but it's designated a historic monument, and I understand that plans are afoot for a restoration. In the foreground, nearest the viewing platform the lower edge of the painting blended into three-dimensional models of fallen soldiers and horses, trampled vegetation, etc., intended to add to the realism, and periodically a tape look played sounds of the battle. These two scenes from it struck me as being among the most photogenic. Directional panels on the handrail of the circular viewing platform point out important events and personages. The column of smoke marks one of several farms that Wellington had occupied as outposts. (One of the things that went wrong for Napoleon that day was that, at the outset of the battle, he sent his brother to attack that outpost, purely as a diversionary tactic to draw Wellington's troops that way before leading his own main body of troops against the British lines elsewhere. The brother, annoyed that he failed actually to take the outpost, persisted in attacking it all day long, tying up his troops there rather than abandoning the ruse and rejoining the main attack once it had begun.) Unlike the WWII battles, which tended to last weeks, and those from WWI, which lasted for months, the battle of Waterloo consisted of three days of build-up and one day of all-out fighting and was then over.

Apparently, several circular panoramic paintings of the battle were made—one, since destroyed, was displayed in London as early as 1815, the year the battle was fought—but the one at Waterloo is the only one that survives. It's showing some obvious roof-leak damage, but it's designated a historic monument, and I understand that plans are afoot for a restoration. In the foreground, nearest the viewing platform the lower edge of the painting blended into three-dimensional models of fallen soldiers and horses, trampled vegetation, etc., intended to add to the realism, and periodically a tape look played sounds of the battle. These two scenes from it struck me as being among the most photogenic. Directional panels on the handrail of the circular viewing platform point out important events and personages. The column of smoke marks one of several farms that Wellington had occupied as outposts. (One of the things that went wrong for Napoleon that day was that, at the outset of the battle, he sent his brother to attack that outpost, purely as a diversionary tactic to draw Wellington's troops that way before leading his own main body of troops against the British lines elsewhere. The brother, annoyed that he failed actually to take the outpost, persisted in attacking it all day long, tying up his troops there rather than abandoning the ruse and rejoining the main attack once it had begun.) Unlike the WWII battles, which tended to last weeks, and those from WWI, which lasted for months, the battle of Waterloo consisted of three days of build-up and one day of all-out fighting and was then over.

Next stop on our "everything" ticket was Napoleon's headquarters, a few kilometers south of the butte. There we visited the various rooms in the farmhouse and got explanations of what happened where—here the emperor's bedroom, there the room where he met with his generals, personal bodyguard troops camped in the garden, etc. In display cases were the actual gray coat he's so often seen wearing in paintings from the time, his death mask, many of his personal effects. Most interesting, I though, was his portable campaign bed. It was designed for him by the court locksmith and was made out of wrought iron rods with folding and locking hinges that permitted it to be folded up quickly and carried on the back of a pack horse. You can see a photo of it, set up but otherwise stripped, at http://www.napoleon.org/en/collectors_corner/object/files/bed_desouches.asp. When we saw it in the museum, it was "dressed" in quilts and comforters and draped with a fabric canopy and curtains.

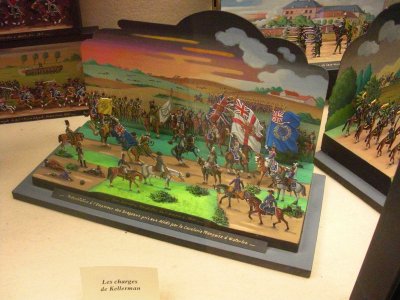

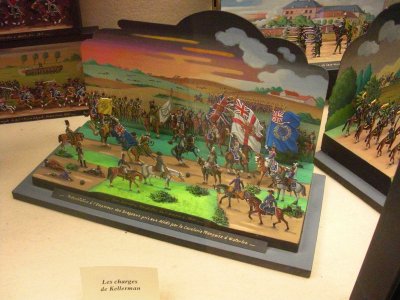

In a back room of the house were displayed a large collection of toy soldiers (many hundreds) carefully painted and outfitted to illustrate all the different regiments, companies, and whatnot involved in the battle) and another large collection, this one of miniature dioramas, probably a hundred of them, again each intended to protray a particular element of the battle. For example, the one on the right is labeled "The charges of Kellerman." The little figures and their horses and flags are flat and are displayed against painted backgrounds, some more realistic than others.

In a back room of the house were displayed a large collection of toy soldiers (many hundreds) carefully painted and outfitted to illustrate all the different regiments, companies, and whatnot involved in the battle) and another large collection, this one of miniature dioramas, probably a hundred of them, again each intended to protray a particular element of the battle. For example, the one on the right is labeled "The charges of Kellerman." The little figures and their horses and flags are flat and are displayed against painted backgrounds, some more realistic than others.

At this point, we had run out of time, so we retired to the hotel to get ready for dinner, leaving the remainder of the attractions for the morning.

I'd had trouble finding a restaurant in Waterloo—David's original choice had changed its schedule and was closed the night we were there, and the second I tried was all booked up. We therefore once again wound up at an Italian place, atypical for us, as we try for French/Belgian restaurants in France and Belgium. L'Opéra was a prototypical upscale Italian restaurant and seemed to be run by prototypical upscale Italians. Out front was the little formal garden with miniature hedges and columnar cypresses, garnished with quite plaster statuary, and inside were dedicated gleaming cast iron, hand-cranked meat slicers holding prosciuttos ready to be sliced to order. The meat slicers were a marvel, razor-sharp blades and absolutely silent operation. Definitely upscale, though—rather than red flocked wallpaper, one whole wall was covered with a large photographic mural of the interior of La Scala.

While we studied the menu, we were served an amuse-bouche of thin sheets of mozzarela rolled with raw ham and herbs (basil, I think). We both chose the "Recommended menu." For the first course, we both passed up the sliced-to-order ham. I had vitello tonnato, a classic dish in which cold, tender, sliced roast veal is drizzled with, yes, tuna sauce. It sounds bizarre, but it works. Fine, olive-oil-packed canned tuna is puréed with seasonings and lots of oil to make a sort of tuna-based mayo which goes beautifully with the veal. On top were caper berries and a cherry tomato.

While we studied the menu, we were served an amuse-bouche of thin sheets of mozzarela rolled with raw ham and herbs (basil, I think). We both chose the "Recommended menu." For the first course, we both passed up the sliced-to-order ham. I had vitello tonnato, a classic dish in which cold, tender, sliced roast veal is drizzled with, yes, tuna sauce. It sounds bizarre, but it works. Fine, olive-oil-packed canned tuna is puréed with seasonings and lots of oil to make a sort of tuna-based mayo which goes beautifully with the veal. On top were caper berries and a cherry tomato.

David's starter was raw, house-marinated salmon with cherry tomatoes, stripes of basil puréed in oil, and special red onions, and he announced himself quite pleased with it.

David's starter was raw, house-marinated salmon with cherry tomatoes, stripes of basil puréed in oil, and special red onions, and he announced himself quite pleased with it.

For the second course, we both had large ravioli (called "agnolotti" on the menu) filled with green asparagus, mascarpone, and Parmesan cheese. The were bathed in a creamy sauce and sprinkled with green onions and asparagus bits. Yummy.

David's main course was slices of rare "contrafilet" of beef with coarse salt, mixed arugula salad, and old balsamic vinegar.

David's main course was slices of rare "contrafilet" of beef with coarse salt, mixed arugula salad, and old balsamic vinegar.

I had medallions of veal, slightly pink inside, in roquefort sauce topped with thin crisp slices of pancetta and sided with rosemary-fried potatoes. Delicious, though I would not have detected the roquefort if the menu had no menitoned it.

For dessert, we both had the "recommended dessert," scrumptious black forest cake.

For dessert, we both had the "recommended dessert," scrumptious black forest cake.

This was the only restaurant we had to drive to and from on the whole trip (all of six blocks, but our feet were tired), and we made the round trip without incident.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

The next morning, the door to the "breakfast room" proved to open into a sunny, expansive (and deserted) dining room with mirrors and cherry paneling. Here, I'm taking a photo of myself and David (and, in the background, the breakfast buffet) in one of the mirrors. A peek down the stairs at the far end of the room revealed that we were in the upstairs portion of the a large and handsome bar, across the street from Wagon Leo, which we'd walked past the previous evening. It didn't say "Leo" on it anywhere, but I suspect it's under the same management. Every now and then, someone would come up from downstairs to check the buffet, but otherwise, we had the place to ourselves.

The next morning, the door to the "breakfast room" proved to open into a sunny, expansive (and deserted) dining room with mirrors and cherry paneling. Here, I'm taking a photo of myself and David (and, in the background, the breakfast buffet) in one of the mirrors. A peek down the stairs at the far end of the room revealed that we were in the upstairs portion of the a large and handsome bar, across the street from Wagon Leo, which we'd walked past the previous evening. It didn't say "Leo" on it anywhere, but I suspect it's under the same management. Every now and then, someone would come up from downstairs to check the buffet, but otherwise, we had the place to ourselves. Waterloo is a fairly small town, now mostly a bedroom community for nearby Brussels. We drove into town from the south on the very road Napoleon was marching along when he got there, and when we came to the crossroads he hoped to capture, we were pretty much on the battlefield. We drove past the farm where he set up his headquarters, now a museum, and we could plainly see, from the main road, the "Butte du Lion" (the Lion Mound), the conical artifical hill that now marks the place where the fighting was thickest—actually, it marks the spot where the crown prince of the Netherlands (of which Belgium was then part) was wounded during the battle, but it comes to the same thing.

Waterloo is a fairly small town, now mostly a bedroom community for nearby Brussels. We drove into town from the south on the very road Napoleon was marching along when he got there, and when we came to the crossroads he hoped to capture, we were pretty much on the battlefield. We drove past the farm where he set up his headquarters, now a museum, and we could plainly see, from the main road, the "Butte du Lion" (the Lion Mound), the conical artifical hill that now marks the place where the fighting was thickest—actually, it marks the spot where the crown prince of the Netherlands (of which Belgium was then part) was wounded during the battle, but it comes to the same thing.

The next order of business was lunch, so we asked for advice at the reception desk. The clerk listed a half-dozen nearby restaurants, but the minute she mentioned Le Pain Quotidien, the choice was made. That's the great bakery where we had two excellent breakfasts in Ghent, and now we got to try its lunch selections. A whole section of the menu was dedicated to "tartines" (bread spread with something) and another to salads. I ordered the tartine of roast beef, mustard, capers and arugula; David had the salad of warm goat cheese with sirop de Liège, apples, raisins and granola. Both delicious. Wish we had a bakery like that around here!

The next order of business was lunch, so we asked for advice at the reception desk. The clerk listed a half-dozen nearby restaurants, but the minute she mentioned Le Pain Quotidien, the choice was made. That's the great bakery where we had two excellent breakfasts in Ghent, and now we got to try its lunch selections. A whole section of the menu was dedicated to "tartines" (bread spread with something) and another to salads. I ordered the tartine of roast beef, mustard, capers and arugula; David had the salad of warm goat cheese with sirop de Liège, apples, raisins and granola. Both delicious. Wish we had a bakery like that around here!

Our admission tickets to the butte's museum also included the chance to climb the butte itself and a few outdoor exhibits, like this Napoleonic-era horse-drawn field forge. The blacksmith presumably set up his anvil (stored in the chest over the large rear wheels?) on the ground and built his fire in the iron section of the wagon, fanning it with the large bellows (itself protected from the heat by the iron screen between it and the fire. Behind the forge inthe photo is a period horse-drawn field ambulance. I also got this photo of one of the three trucks used for the battle-field tour, but if you'll look closely at its front tire, you'll see why the tours were not running that day—flat as the proverbial pancake. All the trucks had the same trouble, which the folks at the museum cashier's desk attributed to vandals.

Our admission tickets to the butte's museum also included the chance to climb the butte itself and a few outdoor exhibits, like this Napoleonic-era horse-drawn field forge. The blacksmith presumably set up his anvil (stored in the chest over the large rear wheels?) on the ground and built his fire in the iron section of the wagon, fanning it with the large bellows (itself protected from the heat by the iron screen between it and the fire. Behind the forge inthe photo is a period horse-drawn field ambulance. I also got this photo of one of the three trucks used for the battle-field tour, but if you'll look closely at its front tire, you'll see why the tours were not running that day—flat as the proverbial pancake. All the trucks had the same trouble, which the folks at the museum cashier's desk attributed to vandals.

At first, we looked at the long straight staircase up the side of the butte and decided it wasn't worth it, but once we realized we might not get to go on the truck tour, we climbed it anyway, for the view of the terrain. For an idea of the scale of the lion and its pedestal, compare it with the people climbing the stairs and the ones at the top, sillouetted against the sky below and to the right of the monument. The butte built shortly after the battle, and when Wellington first saw it, he is said to have exclaimed, "They've spoiled my battlefield!" The view was great. At the top, I listened in amusement for some time to a pair of teenage American boys who were discoursing quite knowledgeably to their parents on the history behind and strategy during the battle and were being very patient, I thought, with the parents' lack of comprehension and/or interest—a definite reversal of the roles you usually see on family trips! The photo at the right shows the museum we had just toured (the rectangular buildings at the right with the three disabled trucks parked next to them) and the round building that houses the 1912 panoramic painting.

At first, we looked at the long straight staircase up the side of the butte and decided it wasn't worth it, but once we realized we might not get to go on the truck tour, we climbed it anyway, for the view of the terrain. For an idea of the scale of the lion and its pedestal, compare it with the people climbing the stairs and the ones at the top, sillouetted against the sky below and to the right of the monument. The butte built shortly after the battle, and when Wellington first saw it, he is said to have exclaimed, "They've spoiled my battlefield!" The view was great. At the top, I listened in amusement for some time to a pair of teenage American boys who were discoursing quite knowledgeably to their parents on the history behind and strategy during the battle and were being very patient, I thought, with the parents' lack of comprehension and/or interest—a definite reversal of the roles you usually see on family trips! The photo at the right shows the museum we had just toured (the rectangular buildings at the right with the three disabled trucks parked next to them) and the round building that houses the 1912 panoramic painting.

Apparently, several circular panoramic paintings of the battle were made—one, since destroyed, was displayed in London as early as 1815, the year the battle was fought—but the one at Waterloo is the only one that survives. It's showing some obvious roof-leak damage, but it's designated a historic monument, and I understand that plans are afoot for a restoration. In the foreground, nearest the viewing platform the lower edge of the painting blended into three-dimensional models of fallen soldiers and horses, trampled vegetation, etc., intended to add to the realism, and periodically a tape look played sounds of the battle. These two scenes from it struck me as being among the most photogenic. Directional panels on the handrail of the circular viewing platform point out important events and personages. The column of smoke marks one of several farms that Wellington had occupied as outposts. (One of the things that went wrong for Napoleon that day was that, at the outset of the battle, he sent his brother to attack that outpost, purely as a diversionary tactic to draw Wellington's troops that way before leading his own main body of troops against the British lines elsewhere. The brother, annoyed that he failed actually to take the outpost, persisted in attacking it all day long, tying up his troops there rather than abandoning the ruse and rejoining the main attack once it had begun.) Unlike the WWII battles, which tended to last weeks, and those from WWI, which lasted for months, the battle of Waterloo consisted of three days of build-up and one day of all-out fighting and was then over.

Apparently, several circular panoramic paintings of the battle were made—one, since destroyed, was displayed in London as early as 1815, the year the battle was fought—but the one at Waterloo is the only one that survives. It's showing some obvious roof-leak damage, but it's designated a historic monument, and I understand that plans are afoot for a restoration. In the foreground, nearest the viewing platform the lower edge of the painting blended into three-dimensional models of fallen soldiers and horses, trampled vegetation, etc., intended to add to the realism, and periodically a tape look played sounds of the battle. These two scenes from it struck me as being among the most photogenic. Directional panels on the handrail of the circular viewing platform point out important events and personages. The column of smoke marks one of several farms that Wellington had occupied as outposts. (One of the things that went wrong for Napoleon that day was that, at the outset of the battle, he sent his brother to attack that outpost, purely as a diversionary tactic to draw Wellington's troops that way before leading his own main body of troops against the British lines elsewhere. The brother, annoyed that he failed actually to take the outpost, persisted in attacking it all day long, tying up his troops there rather than abandoning the ruse and rejoining the main attack once it had begun.) Unlike the WWII battles, which tended to last weeks, and those from WWI, which lasted for months, the battle of Waterloo consisted of three days of build-up and one day of all-out fighting and was then over.

In a back room of the house were displayed a large collection of toy soldiers (many hundreds) carefully painted and outfitted to illustrate all the different regiments, companies, and whatnot involved in the battle) and another large collection, this one of miniature dioramas, probably a hundred of them, again each intended to protray a particular element of the battle. For example, the one on the right is labeled "The charges of Kellerman." The little figures and their horses and flags are flat and are displayed against painted backgrounds, some more realistic than others.

In a back room of the house were displayed a large collection of toy soldiers (many hundreds) carefully painted and outfitted to illustrate all the different regiments, companies, and whatnot involved in the battle) and another large collection, this one of miniature dioramas, probably a hundred of them, again each intended to protray a particular element of the battle. For example, the one on the right is labeled "The charges of Kellerman." The little figures and their horses and flags are flat and are displayed against painted backgrounds, some more realistic than others.

While we studied the menu, we were served an amuse-bouche of thin sheets of mozzarela rolled with raw ham and herbs (basil, I think). We both chose the "Recommended menu." For the first course, we both passed up the sliced-to-order ham. I had vitello tonnato, a classic dish in which cold, tender, sliced roast veal is drizzled with, yes, tuna sauce. It sounds bizarre, but it works. Fine, olive-oil-packed canned tuna is puréed with seasonings and lots of oil to make a sort of tuna-based mayo which goes beautifully with the veal. On top were caper berries and a cherry tomato.

While we studied the menu, we were served an amuse-bouche of thin sheets of mozzarela rolled with raw ham and herbs (basil, I think). We both chose the "Recommended menu." For the first course, we both passed up the sliced-to-order ham. I had vitello tonnato, a classic dish in which cold, tender, sliced roast veal is drizzled with, yes, tuna sauce. It sounds bizarre, but it works. Fine, olive-oil-packed canned tuna is puréed with seasonings and lots of oil to make a sort of tuna-based mayo which goes beautifully with the veal. On top were caper berries and a cherry tomato.

David's starter was raw, house-marinated salmon with cherry tomatoes, stripes of basil puréed in oil, and special red onions, and he announced himself quite pleased with it.

David's starter was raw, house-marinated salmon with cherry tomatoes, stripes of basil puréed in oil, and special red onions, and he announced himself quite pleased with it.

David's main course was slices of rare "contrafilet" of beef with coarse salt, mixed arugula salad, and old balsamic vinegar.

David's main course was slices of rare "contrafilet" of beef with coarse salt, mixed arugula salad, and old balsamic vinegar. For dessert, we both had the "recommended dessert," scrumptious black forest cake.

For dessert, we both had the "recommended dessert," scrumptious black forest cake.