Tuesday, 14 June 2011: Anse/Bagnols to Collonges au Mont d'Or (Bocuse!)

Written 29 June 2011

Tuesday morning, Pentacost behind us, we once again set off for the Anse tourist office, just to make sure we'd given the place a chance. This time, I had my camera with me, so I got the photos I should have gotten the day before. At the left is a photo of the local sidewalk paving, which I found less intuitive and more interesting than the hexagons more common around here. Each block is about the size of my hand. At the right is a work of art (Les Pyramides, by Marc da Costa) installed in the town square, between the church and the town hall. The three pyramids are metal and hollow, and each has many designs cut into it. The plaque in the foreground gives extensive explanations of what the designs are supposed to represent.

Tuesday morning, Pentacost behind us, we once again set off for the Anse tourist office, just to make sure we'd given the place a chance. This time, I had my camera with me, so I got the photos I should have gotten the day before. At the left is a photo of the local sidewalk paving, which I found less intuitive and more interesting than the hexagons more common around here. Each block is about the size of my hand. At the right is a work of art (Les Pyramides, by Marc da Costa) installed in the town square, between the church and the town hall. The three pyramids are metal and hollow, and each has many designs cut into it. The plaque in the foreground gives extensive explanations of what the designs are supposed to represent.

We also took time to examine more closely what we had taken to be scaffolding surrounding the church's spire and concluded that it was probably, instead, simply a steeple of very modern design. It lights up at night.

Having visited the Office de Tourisme and verified that we had, in fact, visited what there was to visit (except the tourist train, which we'd missed our chance at, and the vinyard tours, which don't start until July), we sat on a park bench with our handful of brochures to consider how to spend the day. Our dinner reservations were in Collonges au Mont d'Or (chez Bocuse!), where no one had ever claimed there was anything else to do (except drive to the top of the mountain to look at the view) and which was quite closeby, so we had most of the day in hand. We had driven all over the Beaujolais country but didn't feel we'd gotten to know it or its wine as well as we'd like. David's reluctance to take advantage of wine-makers' willingness to offer tastes when he knew he wasn't in a position to buy, together with the complete absence of organized vinyard or winery tours, had left us wondering how to learn more.

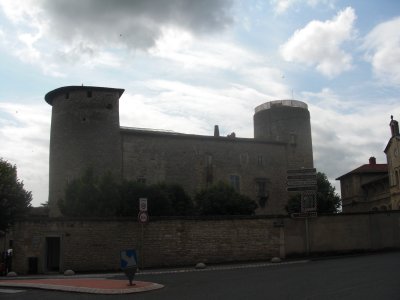

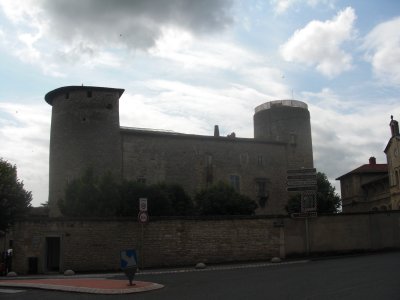

Among the brochures, though, was one for the Hameau George DuBoeuf. David had noticed it earlier but considered it too corny for words, and we'd driven by it earlier in the week, David said, but I'd been looking the other way. But it advertised a museum of Beaujolais, a wine-bottling operation, and a tasting room, so what the heck—we took a last photo of Anse's two-towered château and then drove back north to Romanèche-Thorins, south of Mâcon, where we'd had lunch at the Moulin-à-Vent restaurant earlier, to visit the hameau.

Among the brochures, though, was one for the Hameau George DuBoeuf. David had noticed it earlier but considered it too corny for words, and we'd driven by it earlier in the week, David said, but I'd been looking the other way. But it advertised a museum of Beaujolais, a wine-bottling operation, and a tasting room, so what the heck—we took a last photo of Anse's two-towered château and then drove back north to Romanèche-Thorins, south of Mâcon, where we'd had lunch at the Moulin-à-Vent restaurant earlier, to visit the hameau.

Georges DeBoeuf is a wine "négociant"; that is, a wine broker. He contracts with wine producers to buy their newly made wine, ages and blends it himself, bottles it, and sells it (much of it in the U.S.) with his "seal of approval." Check the Beaujolais wines in any American wine store and you'll surely see a Georges DuBoeuf selection or two—he's turned himself into Mr. Beaujolais, at least in the U.S. And back here in the wine country, he's turned himself into a sort of theme park, the Hameau George DuBoeuf (the Georges DuBoeuf Hamlet). It's built around the historic Romanèche-Thorins train station, where he got his start shipping wines, and it includes, as far as we could tell, his real aging and bottling operations, in addition to the museum, a restaurant, a botanical garden, and a tasting room clearly set up to handle multiple tour buses simultaneously. A little tourist train (on rubber tires, without tracks) ferries visitors among the various buildings.

Since we were back in Romanèche-Thorins, though, we first went to lunch at La Maison Blanche, which had been closed when we passed through before. The amuse-bouche was glasses of cold green-pea soup topped with a layer of sweet tomato gazpacho. Very good.

Since we were back in Romanèche-Thorins, though, we first went to lunch at La Maison Blanche, which had been closed when we passed through before. The amuse-bouche was glasses of cold green-pea soup topped with a layer of sweet tomato gazpacho. Very good.

Then David had a "salade Beaujolaise," which, as I remarked to the waiter, seem, from the menu description to be identical to a salade Lyonnaise. He admitted that, for a real salade Beaujolaise, the egg would be poached in red wine, but these days, nobody bothers—they just use a regular poached egg.

I had this excellent seafood salad, with grilled shrimp and scallops; the salad consisted mainly of "mâche," lamb's lettuce, garnished with whole Belgian endive leaves, sliced radishes, and dill sprigs.

I had this excellent seafood salad, with grilled shrimp and scallops; the salad consisted mainly of "mâche," lamb's lettuce, garnished with whole Belgian endive leaves, sliced radishes, and dill sprigs.

Then we crossed the road to check out the hameau, billed as "The First Oenopark!" Its entrance courtyard is graced by this antique train, no longer in use.

All in all, we were favorably impressed. We started with the museum and spent so much time there that we had time for only a session in the tasting room and a quick look through the gift shop before we had to start for Collonges. We never did get to the winery itself.

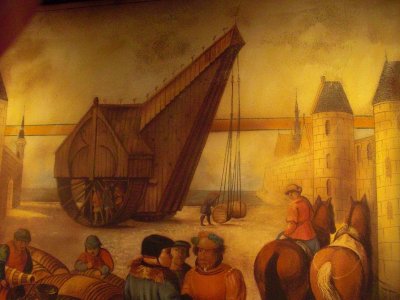

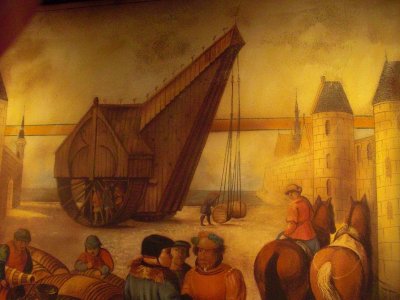

The museum started with an extensive display on the history of, not wine making, but—as befits Georges DuBoeuf—the wine trade. At the left is an illustration of an early mobile crane powered by guys walking inside a treadwheel.

The museum started with an extensive display on the history of, not wine making, but—as befits Georges DuBoeuf—the wine trade. At the left is an illustration of an early mobile crane powered by guys walking inside a treadwheel.

At the right is a model illustrating how amphorae of wine would be packed in the hold of a ship in Gallo-Roman times. We also learned the story of the first guy who had the idea of marketing Beaujolais wines in Paris. In the slack season, he hitched up his oxen, loaded his cart with three barrels of wine, and set off—it took him three weeks to get there, but the enterprise was such a success (the king bought his whole supply and raved aboutit) that it soon spawned a regular trade.

Next were extensive displays on what it has taken, historically, to keep vines growing and health, especially how the French wine growers have coped with the various pests and diseases that have swept the vineyards since the discovery of the New World—various insects, powdery mildew, downy mildew, and, worst of all, Phylloxera. The exhibits included a huge range of hand-pumped spraying equipment, from hand-held to back packs to miniature editions of horse-drawn fire-engines. Then displays of antique racking and bottling gear, the usual one on barrel-making and the making of corks. We also saw wine-related art—my favorite was César's "Compression de tastevin" ("Compression of wine-tasting cups"), which was just that—a foot-square, three-foot high brick of shiny, silver crushed wine-tasting cups!

The next stage of the museum was a series of three shows, to be seen in order, for the first of which we had to wait 20 minutes. At this point, the influence of Disney made itself apparent. In what was clearly the holding tank for people waiting for the show, a lighted sign displayed the countdown to the next showing, while a large slideshow on one wall entertained us during the wait. The slide show was actually excellent. On series illustrated every step in the process of grafting new vine shoots onto Phylloxera-resistant rootstock, in much greater detail than I'd ever seen, including all the steps between the actual grafting process and the planting of the new vine. Another took us through the geology of the Mâconnais and Beaujolais regions, explaining the differences in soil composition that contributed to the different characters of the wines—basically, the Mâconnais is calcareous, whereas the Beaujolais is granitic. In addition, for example, Moulin-à-Vent wines get their distinctive character from the high manganese content of the soil in that small area (on display was a three-foot manganese nodule, just to back up the claim), whereas Mont Brouilly benefits from high magnesium levels.

Another excellent display was a relief map of the Beaujolais region with a tiny light marking each village. (The Mâconnais is clearly named for Mâcon, the Côtes de Beaune for Beaune, etc., but I had never realized that the Beaujolais is named for the little village of Beaujeu, which you never hear about otherwise.) The Saône was in the foreground, running from right to left (north to south) in front of the viewer. In the center, on the river, was Villefranche, "wine capital," of the Beaujolais. Spread like a fan over the hills beyond Villefranche were the 20 or so villages of the Beaujolais. The map cycled through a series of explanations of soil type and wine character, working its way from left to right, illuminating the cluster of villages to which each explanation pertained. Very helpful.

Anyway, the 20 minutes until showtime finally wore away, and we were looking forward to sitting down in the theater, having been standing in one place for a good while, which is hard on the feet. The doors opened, and we entered the theater (the only ones present for this showing) only to find that it had no chairs, only rails on which to lean your backside. Drat. But being resourceful tourists, we grasped the rails from behind, scooted our feet underneath, and slid down to sit on the risers, resting our arms and chins on the rail. Not bad. But the show was awful. Disney again. The whole thing was 60's-vintage audioanimatronic, framed as a dialog between an old winegrower, seated in a rocking chair and accompanied by his audioanimatronic dog at one side of the stage, and a seductively feminine talking grapevine, gently waving her branches and tendrils and speaking through a knothole on the other. Across the middle streamed cadres of mechanical winegrowers representing various eras in the history of wine making. We would have walked out, but we found that, like Disney productions, this one was fully automated. The doors (without handles) closed as the show began, and the only option for leaving early was to press the "emergency" button. So we sat throught the 20-minute show until they let us out—at least we got to rest our feet.

The next show, timed to begin shortly after we left the first, was quite a lovely narrated slide montage about the vineyards of the region. We even got chairs. No complaints.

The third, again timed for our exit from the second, was ridiculous but fun. It was a dizzying, effervescent, 3D, live-action musical, framed as a magical journey. Some favorite son of the area (an actor, I think) is joined in his train compartment, on his way home to the region, by a beautiful but mysterious young woman who we (the viewers) know to be the goddess of wine in disguise. It was rather short on plot but featured many scenes of a joyous young band of singing, dancing grape pickers (working in the vineyards, dancing along the roads, picnicking in the bunkhouse, etc.) and a great scene set in Paul Bocuse's kitchen that featured Bocuse himself (we see him casually fling a Bresse chicken into a pig's bladder, held open by an assistant, for one of his classic dishes), Bernard Pivot (beloved French literary figure and TV personality, also a local favorite son), and others. David rolled his eyes, but I got a kick out of it.

Then more museum, increasingly centering on George DuBoeuf wines and including a fictional scene set in a wine bistro featuring wax figures of some of the most influential people in the history of Beaujolais wine, and terminating in the tasting room, which was huge. You could easily have held a wedding reception for 300 in there. Besides a vast tasting bar, tended by a knowledgeable young man who had nothing better to do than serve us, as we were once again the only people there, it was equipped with an antique carousel horse; a huge, glowing, neon-encrusted antique Wurlitzer juke box; an enormous calliope (maybe 30 feet wide by 10 high, shown at left); and, in a corner to the right of the calliope, the life-size mechanical duo in the right-hand photo that, as the drum promises, played accordion jazz.

Then more museum, increasingly centering on George DuBoeuf wines and including a fictional scene set in a wine bistro featuring wax figures of some of the most influential people in the history of Beaujolais wine, and terminating in the tasting room, which was huge. You could easily have held a wedding reception for 300 in there. Besides a vast tasting bar, tended by a knowledgeable young man who had nothing better to do than serve us, as we were once again the only people there, it was equipped with an antique carousel horse; a huge, glowing, neon-encrusted antique Wurlitzer juke box; an enormous calliope (maybe 30 feet wide by 10 high, shown at left); and, in a corner to the right of the calliope, the life-size mechanical duo in the right-hand photo that, as the drum promises, played accordion jazz.

David had thought in advance about the comparisons he wanted to make, so he asked the bartender for tastes of a Moulin-à-vent, a Juliénas, and a Saint-Amour, which he later said told him just what he wanted to know. With them, we were served a little plate of baguette slices, each topped with a slice of "rosette de Lyon" sausage.

We would have liked to visit the other parts of the "oenopark," but by then, it was really time for us to head back south toward our hotel for the night, so after a brief look at the gift shop, we bid a fond farewell to Romanèche-Thorins. If we ever get back there, I'd really like to see the "Musée de Compagnonage," a museum of "masterpieces"—the objects made by graduating apprentices to demonstrate their mastery. The photos on the website are beautiful. For such a little town, that place has a lot to offer!

Collonges au Mont d'Or is actually a northern suburb of Lyon (one of several that are called "au Mont d'Or" because they are all on a large mountain north of the city that is literally golden, from the color of its soil and stone), on the west bank of the Saône, and our hotel was easy to find—just get on the main road that hugs the west bank of the Saône (i.e., take a right out of the museum's parking lot), then follow it south until you come to the hotel. About a kilometer beyond that, you come to the Auberge du Pont de Collonges, the legendary restaurant of Paul Bocuse, at which we had dinner reservations. We were entirely cracked up to see, as we approached the area, a straight-faced white road sign reading "Paul Bocuse, 3 km." Bocuse was recently declared, by the Culinary Institute of America and the Gault-Millau people, the chef of the century—his place is, and has been for decades, a national and international destination.

I was doubly amused when the name of the street dawned on me. Both the hotel and Bocuse's restaurant are on the Quai Illhaeusern, which struck me as an odd name for the region, but it sounded familiar. Then I saw the little sign announcing that Collonges was twinned with the town of Illhaeusern, near Strasbourg, location of the Auberge de l'Ill, the three-star restaurant of the late Paul Haeberlin, probably the second most legendary chef in France. I looked it up, and sure enough, Haeberlin's place is on rue Collonges au Mont d'Or!

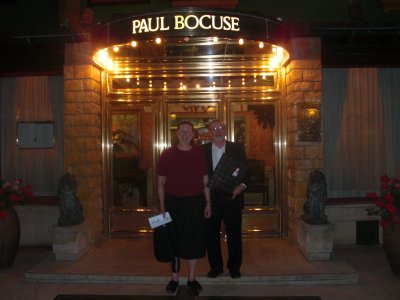

If George Duboeuf has turned himself into a theme park, Bocuse has built himself a temple. Here's what it looks like, as we approached it—we just walked along the highway from the hotel; no sidewalk, but the grass and gravel shoulder was wide enough. Its grandiose canopied glass entrance, with "Paul Bocuse" in three-foot illuminated letters, is on the far end. Note the portrait of the man himself, framed in a faux window on the side. Those arriving from Lyon can apparently see it for a long while before they get there, and they drive directly toward it over the bridge that ends at its doorstep.

If George Duboeuf has turned himself into a theme park, Bocuse has built himself a temple. Here's what it looks like, as we approached it—we just walked along the highway from the hotel; no sidewalk, but the grass and gravel shoulder was wide enough. Its grandiose canopied glass entrance, with "Paul Bocuse" in three-foot illuminated letters, is on the far end. Note the portrait of the man himself, framed in a faux window on the side. Those arriving from Lyon can apparently see it for a long while before they get there, and they drive directly toward it over the bridge that ends at its doorstep.

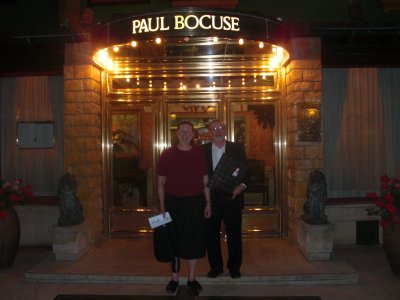

We were met at the entrance by the door man, an old guy in a bright-red and gold bell-hop's uniform. As each party leaves, he routinely hands them a souvenir menu and asks for their camera so that he can take souvenir pictures of them in front of the entrance, holding the menu. He takes one framing just the doorway (with the one-foot illuminated letters) and another from further back, framing the facade with the three-foot letters, higher up. He's had lots of practice.

The amuse-bouche was a cold cream of green pea soup drizzled with herb oil, and it was one of those "oooh!" experiences. You could hear the people at each table go "oooh!" at the first taste of it, as did we. It was really, really good.

We ordered the "Classique" menu, because David, who had done considerable research on Bocuse's cooking and heard all about him on "Champs Élysées, especially wanted to have the lobster à l'armoricaine and the whole "loupe de mer" (literally "sea wolf," another name for "bar," sea bass) cooked in puff pastry with sauce choron.

We ordered the "Classique" menu, because David, who had done considerable research on Bocuse's cooking and heard all about him on "Champs Élysées, especially wanted to have the lobster à l'armoricaine and the whole "loupe de mer" (literally "sea wolf," another name for "bar," sea bass) cooked in puff pastry with sauce choron.

Here are David's lobster, on the left, and my quenelle de brochet on the right. The quenelle turned out to be the "Lyonnais" style I had seen in so many places in Lyon rather than what I now think of as the "country style" I had in Bourg-en-Bresse. As you can see, though, it was not the perfect cylinder most places were serving but a more free-form shape, although clearly molded in a skin of some sort, as the surface was perfectly smooth. Inside, it was light, but it was much more like a seafood sausage or boudin than like a dumpling. Good, but I think I still prefer the other style. It was napped with a Nantua sauce (tomato-cream sauce with crayfish tails) full of small mushroom bits.

And here's our legendary "Loup en croûte feuilletée, sauce choron," for two. The decorations around the edge are half lemon slices. The lemon peel was grooved, end to end, into sixths, and alternating grooves were dyed with red and green food coloring before the lemon was sliced. I wish it were possible to get the waiters to just leave the fish on the table so that we could take it apart ourselves, but the place was really busy, and they clearly have their routine. The minute I had gotten my photo, the waiter set it on a small service table (the place was knee deep in little rectangular service tables, more than one per dining table) and, at top speed, sliced through the pastry all the way around the edge; lifted off the top crust, set it aside and chopped it into segments; cut off and removed segments of the top layer of the fish underneath to place on each of our plates; topped each portion with a section of pastry; swozzled choron sauce all around it; gave us extra portions of the pastry on side plates; and whisked the remains (more than half the fish) off to the kitchen—we never saw it again. Two is the minimum number of people who can order the dish. When four order it, I hope they use the same size fish, as there was plenty for more people. Sauce choron is béarnaise sauce spiked with a little tomato concentrate; béarnaise, in turn, is hollandaise in which the lemon juice is replaced with a mixture of white wine and white wine vinegar cooked down with shallots, salt, pepper, and tarragon. The dish was very, very good, but I still wish I could have served it myself.

And here's our legendary "Loup en croûte feuilletée, sauce choron," for two. The decorations around the edge are half lemon slices. The lemon peel was grooved, end to end, into sixths, and alternating grooves were dyed with red and green food coloring before the lemon was sliced. I wish it were possible to get the waiters to just leave the fish on the table so that we could take it apart ourselves, but the place was really busy, and they clearly have their routine. The minute I had gotten my photo, the waiter set it on a small service table (the place was knee deep in little rectangular service tables, more than one per dining table) and, at top speed, sliced through the pastry all the way around the edge; lifted off the top crust, set it aside and chopped it into segments; cut off and removed segments of the top layer of the fish underneath to place on each of our plates; topped each portion with a section of pastry; swozzled choron sauce all around it; gave us extra portions of the pastry on side plates; and whisked the remains (more than half the fish) off to the kitchen—we never saw it again. Two is the minimum number of people who can order the dish. When four order it, I hope they use the same size fish, as there was plenty for more people. Sauce choron is béarnaise sauce spiked with a little tomato concentrate; béarnaise, in turn, is hollandaise in which the lemon juice is replaced with a mixture of white wine and white wine vinegar cooked down with shallots, salt, pepper, and tarragon. The dish was very, very good, but I still wish I could have served it myself.

At this point, the timing broke down. The worst thing that can happen during one of these big, multicourse restaurant meals is a long wait between courses. We could feel our blood sugar rising, and our appetities concomitantly waning, as we looked wistfully down the long narrow room to the cheese tray, becalmed at the far end. The restaurant is always booked solid, d demand for tables is high. We're usually among the first to arrive at our restaurants, but some people, just to get in, had chosen dinner hours earlier than they would normally have, and rather earlier than ours. They reached their dessert course while we were still waiting for cheese. The way dessert seems to work there is that they offer you the entire panoply of sweets and let you choose as much or as many as you please. But they don't just bring a tray showing samples or use a trolley. Instead they bring out a full tray of every dessert they make (the menu lists baba au rhum, floating island, shortbread tart of seasonal fruit, fresh fruit salad, Beaujolais style bowl of red fruits, crême brulée, "Gâteau Président Maurice Bernachon," housemade ice creams and sorbets; and seasonal desserts. That last covers a lot of territory, as I saw many more items than were listed. The result is that all the service tables are called into play and paved with trays of desserts. The room is so crowded with dining tables, service tables, and hurried personnel that you can't even see all the desserts being offered, let alone make a rational decision. Every time a different table is ready to order cheese or dessert, all the trays are shifted—and it's like those puzzles where you have only one vacant square and have to move all the other around to form the pattern you want. All the waiters were continually engaged in shifting tables, trays, cheese, etc., and none has room to maneuver. We waited a looong time for this cheese tray to make its way down the room to us. David chose Brillat-Savarin, Saint Marcellin, and a blue (shown here), and I had Brillat-Savarin, Saint Marcellin, and Pouligny St. Pierre.

At this point, the timing broke down. The worst thing that can happen during one of these big, multicourse restaurant meals is a long wait between courses. We could feel our blood sugar rising, and our appetities concomitantly waning, as we looked wistfully down the long narrow room to the cheese tray, becalmed at the far end. The restaurant is always booked solid, d demand for tables is high. We're usually among the first to arrive at our restaurants, but some people, just to get in, had chosen dinner hours earlier than they would normally have, and rather earlier than ours. They reached their dessert course while we were still waiting for cheese. The way dessert seems to work there is that they offer you the entire panoply of sweets and let you choose as much or as many as you please. But they don't just bring a tray showing samples or use a trolley. Instead they bring out a full tray of every dessert they make (the menu lists baba au rhum, floating island, shortbread tart of seasonal fruit, fresh fruit salad, Beaujolais style bowl of red fruits, crême brulée, "Gâteau Président Maurice Bernachon," housemade ice creams and sorbets; and seasonal desserts. That last covers a lot of territory, as I saw many more items than were listed. The result is that all the service tables are called into play and paved with trays of desserts. The room is so crowded with dining tables, service tables, and hurried personnel that you can't even see all the desserts being offered, let alone make a rational decision. Every time a different table is ready to order cheese or dessert, all the trays are shifted—and it's like those puzzles where you have only one vacant square and have to move all the other around to form the pattern you want. All the waiters were continually engaged in shifting tables, trays, cheese, etc., and none has room to maneuver. We waited a looong time for this cheese tray to make its way down the room to us. David chose Brillat-Savarin, Saint Marcellin, and a blue (shown here), and I had Brillat-Savarin, Saint Marcellin, and Pouligny St. Pierre.

Next, during the looong wait for the desserts to migrate our way, while the heat continued to rise in the room, we were served a predessert of a little pot of chocolate cream so thick, rich, and intensely chocolate that I couldn't eat more than a couple of small spoonfuls, especially right after all that cheese.

Next, during the looong wait for the desserts to migrate our way, while the heat continued to rise in the room, we were served a predessert of a little pot of chocolate cream so thick, rich, and intensely chocolate that I couldn't eat more than a couple of small spoonfuls, especially right after all that cheese.

It was accompanied by this double tray of mignardises—chocolates, chocolate-covered candied citrus peel, fruit paste, macaroons, meringues, and the little green thing, which I wish I'd gotten a better picture of. It was a cluster of green hazelnut fruits, with their husks, molded out of marzipan and "toasted" a little (probably with a blowtorch) to simulate the color of the ripening fruit. Each one enclosed a whole hazelnut.

When the dessert waiter finally turned his attention to us, I couldn't face anything sticky sweet, starchy, or chocolate, and definitely nothing hot. He was really disappointed when I just asked for some strawberries and talked me into having at least some housemade vanilla ice cream with them, and of course, he made little decorative designs in the sauce.

When the dessert waiter finally turned his attention to us, I couldn't face anything sticky sweet, starchy, or chocolate, and definitely nothing hot. He was really disappointed when I just asked for some strawberries and talked me into having at least some housemade vanilla ice cream with them, and of course, he made little decorative designs in the sauce.

David had another baba au rhum, and he said the custard on top was excellent. Too bad the timing didn't work out better, so that we could have done justice to the last couple of courses. Maybe we should try for an earlier reservation next time, to get through the main meal before the cheese-and-dessert gridlock develops.

Here's the door man, late in the evening, when he came into the dining room to help with the ushering of parties that had finished eating (all the waiters were shifting desserts). At the right is the photo of us he took outside the door as we left (with the smaller of the lighted letters).

Here's the door man, late in the evening, when he came into the dining room to help with the ushering of parties that had finished eating (all the waiters were shifting desserts). At the right is the photo of us he took outside the door as we left (with the smaller of the lighted letters).

But the highlight of the evening came between the first and second courses. We joked on the way over, asking ourselves whether the restaurant employed a double for Bocuse to walk through the dining room shaking hands. We figured the real one must be not only at least 80 years old but constantly on the road promoting and supervising his various enterprises.

Imagine my surprise on looking up to see the man himself (and if it was a double, it was a darned good one) coming toward us down the dining room! He stopped at every table, shaking hands and asking with obviously sincerity whether everyone was having a good time. An experienced waiter was always at his elbow, in case of difficulties—he really is 85 but walked pretty darn steadily nonetheless. As he approached us, I was going to take his picture, but he said, "No, no, you should be in the photo." He had the waiter take my camera, moved David around to my side of the table, and below you see the result.

We asked the waiter afterward whether Bocuse is often in the restaraunt and whether he often comes into the dining room. He replied, with obvious affection, that Bocuse lives above the restaurant and travels very seldom. He doesn't usually work in the kitchen during meals, but every lunchtime and every dinnertime, he suits up in his crisp chef's whites, dons his tall toque, and comes downstairs to visit with the diners and pose for photos.

We asked the waiter afterward whether Bocuse is often in the restaraunt and whether he often comes into the dining room. He replied, with obvious affection, that Bocuse lives above the restaurant and travels very seldom. He doesn't usually work in the kitchen during meals, but every lunchtime and every dinnertime, he suits up in his crisp chef's whites, dons his tall toque, and comes downstairs to visit with the diners and pose for photos.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Tuesday morning, Pentacost behind us, we once again set off for the Anse tourist office, just to make sure we'd given the place a chance. This time, I had my camera with me, so I got the photos I should have gotten the day before. At the left is a photo of the local sidewalk paving, which I found less intuitive and more interesting than the hexagons more common around here. Each block is about the size of my hand. At the right is a work of art (Les Pyramides, by Marc da Costa) installed in the town square, between the church and the town hall. The three pyramids are metal and hollow, and each has many designs cut into it. The plaque in the foreground gives extensive explanations of what the designs are supposed to represent.

Tuesday morning, Pentacost behind us, we once again set off for the Anse tourist office, just to make sure we'd given the place a chance. This time, I had my camera with me, so I got the photos I should have gotten the day before. At the left is a photo of the local sidewalk paving, which I found less intuitive and more interesting than the hexagons more common around here. Each block is about the size of my hand. At the right is a work of art (Les Pyramides, by Marc da Costa) installed in the town square, between the church and the town hall. The three pyramids are metal and hollow, and each has many designs cut into it. The plaque in the foreground gives extensive explanations of what the designs are supposed to represent. Among the brochures, though, was one for the Hameau George DuBoeuf. David had noticed it earlier but considered it too corny for words, and we'd driven by it earlier in the week, David said, but I'd been looking the other way. But it advertised a museum of Beaujolais, a wine-bottling operation, and a tasting room, so what the heck—we took a last photo of Anse's two-towered château and then drove back north to Romanèche-Thorins, south of Mâcon, where we'd had lunch at the Moulin-à-Vent restaurant earlier, to visit the hameau.

Among the brochures, though, was one for the Hameau George DuBoeuf. David had noticed it earlier but considered it too corny for words, and we'd driven by it earlier in the week, David said, but I'd been looking the other way. But it advertised a museum of Beaujolais, a wine-bottling operation, and a tasting room, so what the heck—we took a last photo of Anse's two-towered château and then drove back north to Romanèche-Thorins, south of Mâcon, where we'd had lunch at the Moulin-à-Vent restaurant earlier, to visit the hameau.

Since we were back in Romanèche-Thorins, though, we first went to lunch at La Maison Blanche, which had been closed when we passed through before. The amuse-bouche was glasses of cold green-pea soup topped with a layer of sweet tomato gazpacho. Very good.

Since we were back in Romanèche-Thorins, though, we first went to lunch at La Maison Blanche, which had been closed when we passed through before. The amuse-bouche was glasses of cold green-pea soup topped with a layer of sweet tomato gazpacho. Very good.

I had this excellent seafood salad, with grilled shrimp and scallops; the salad consisted mainly of "mâche," lamb's lettuce, garnished with whole Belgian endive leaves, sliced radishes, and dill sprigs.

I had this excellent seafood salad, with grilled shrimp and scallops; the salad consisted mainly of "mâche," lamb's lettuce, garnished with whole Belgian endive leaves, sliced radishes, and dill sprigs.

The museum started with an extensive display on the history of, not wine making, but—as befits Georges DuBoeuf—the wine trade. At the left is an illustration of an early mobile crane powered by guys walking inside a treadwheel.

The museum started with an extensive display on the history of, not wine making, but—as befits Georges DuBoeuf—the wine trade. At the left is an illustration of an early mobile crane powered by guys walking inside a treadwheel.

Then more museum, increasingly centering on George DuBoeuf wines and including a fictional scene set in a wine bistro featuring wax figures of some of the most influential people in the history of Beaujolais wine, and terminating in the tasting room, which was huge. You could easily have held a wedding reception for 300 in there. Besides a vast tasting bar, tended by a knowledgeable young man who had nothing better to do than serve us, as we were once again the only people there, it was equipped with an antique carousel horse; a huge, glowing, neon-encrusted antique Wurlitzer juke box; an enormous calliope (maybe 30 feet wide by 10 high, shown at left); and, in a corner to the right of the calliope, the life-size mechanical duo in the right-hand photo that, as the drum promises, played accordion jazz.

Then more museum, increasingly centering on George DuBoeuf wines and including a fictional scene set in a wine bistro featuring wax figures of some of the most influential people in the history of Beaujolais wine, and terminating in the tasting room, which was huge. You could easily have held a wedding reception for 300 in there. Besides a vast tasting bar, tended by a knowledgeable young man who had nothing better to do than serve us, as we were once again the only people there, it was equipped with an antique carousel horse; a huge, glowing, neon-encrusted antique Wurlitzer juke box; an enormous calliope (maybe 30 feet wide by 10 high, shown at left); and, in a corner to the right of the calliope, the life-size mechanical duo in the right-hand photo that, as the drum promises, played accordion jazz.

If George Duboeuf has turned himself into a theme park, Bocuse has built himself a temple. Here's what it looks like, as we approached it—we just walked along the highway from the hotel; no sidewalk, but the grass and gravel shoulder was wide enough. Its grandiose canopied glass entrance, with "Paul Bocuse" in three-foot illuminated letters, is on the far end. Note the portrait of the man himself, framed in a faux window on the side. Those arriving from Lyon can apparently see it for a long while before they get there, and they drive directly toward it over the bridge that ends at its doorstep.

If George Duboeuf has turned himself into a theme park, Bocuse has built himself a temple. Here's what it looks like, as we approached it—we just walked along the highway from the hotel; no sidewalk, but the grass and gravel shoulder was wide enough. Its grandiose canopied glass entrance, with "Paul Bocuse" in three-foot illuminated letters, is on the far end. Note the portrait of the man himself, framed in a faux window on the side. Those arriving from Lyon can apparently see it for a long while before they get there, and they drive directly toward it over the bridge that ends at its doorstep.

We ordered the "Classique" menu, because David, who had done considerable research on Bocuse's cooking and heard all about him on "Champs Élysées, especially wanted to have the lobster à l'armoricaine and the whole "loupe de mer" (literally "sea wolf," another name for "bar," sea bass) cooked in puff pastry with sauce choron.

We ordered the "Classique" menu, because David, who had done considerable research on Bocuse's cooking and heard all about him on "Champs Élysées, especially wanted to have the lobster à l'armoricaine and the whole "loupe de mer" (literally "sea wolf," another name for "bar," sea bass) cooked in puff pastry with sauce choron.

And here's our legendary "Loup en croûte feuilletée, sauce choron," for two. The decorations around the edge are half lemon slices. The lemon peel was grooved, end to end, into sixths, and alternating grooves were dyed with red and green food coloring before the lemon was sliced. I wish it were possible to get the waiters to just leave the fish on the table so that we could take it apart ourselves, but the place was really busy, and they clearly have their routine. The minute I had gotten my photo, the waiter set it on a small service table (the place was knee deep in little rectangular service tables, more than one per dining table) and, at top speed, sliced through the pastry all the way around the edge; lifted off the top crust, set it aside and chopped it into segments; cut off and removed segments of the top layer of the fish underneath to place on each of our plates; topped each portion with a section of pastry; swozzled choron sauce all around it; gave us extra portions of the pastry on side plates; and whisked the remains (more than half the fish) off to the kitchen—we never saw it again. Two is the minimum number of people who can order the dish. When four order it, I hope they use the same size fish, as there was plenty for more people. Sauce choron is béarnaise sauce spiked with a little tomato concentrate; béarnaise, in turn, is hollandaise in which the lemon juice is replaced with a mixture of white wine and white wine vinegar cooked down with shallots, salt, pepper, and tarragon. The dish was very, very good, but I still wish I could have served it myself.

And here's our legendary "Loup en croûte feuilletée, sauce choron," for two. The decorations around the edge are half lemon slices. The lemon peel was grooved, end to end, into sixths, and alternating grooves were dyed with red and green food coloring before the lemon was sliced. I wish it were possible to get the waiters to just leave the fish on the table so that we could take it apart ourselves, but the place was really busy, and they clearly have their routine. The minute I had gotten my photo, the waiter set it on a small service table (the place was knee deep in little rectangular service tables, more than one per dining table) and, at top speed, sliced through the pastry all the way around the edge; lifted off the top crust, set it aside and chopped it into segments; cut off and removed segments of the top layer of the fish underneath to place on each of our plates; topped each portion with a section of pastry; swozzled choron sauce all around it; gave us extra portions of the pastry on side plates; and whisked the remains (more than half the fish) off to the kitchen—we never saw it again. Two is the minimum number of people who can order the dish. When four order it, I hope they use the same size fish, as there was plenty for more people. Sauce choron is béarnaise sauce spiked with a little tomato concentrate; béarnaise, in turn, is hollandaise in which the lemon juice is replaced with a mixture of white wine and white wine vinegar cooked down with shallots, salt, pepper, and tarragon. The dish was very, very good, but I still wish I could have served it myself.

At this point, the timing broke down. The worst thing that can happen during one of these big, multicourse restaurant meals is a long wait between courses. We could feel our blood sugar rising, and our appetities concomitantly waning, as we looked wistfully down the long narrow room to the cheese tray, becalmed at the far end. The restaurant is always booked solid, d demand for tables is high. We're usually among the first to arrive at our restaurants, but some people, just to get in, had chosen dinner hours earlier than they would normally have, and rather earlier than ours. They reached their dessert course while we were still waiting for cheese. The way dessert seems to work there is that they offer you the entire panoply of sweets and let you choose as much or as many as you please. But they don't just bring a tray showing samples or use a trolley. Instead they bring out a full tray of every dessert they make (the menu lists baba au rhum, floating island, shortbread tart of seasonal fruit, fresh fruit salad, Beaujolais style bowl of red fruits, crême brulée, "Gâteau Président Maurice Bernachon," housemade ice creams and sorbets; and seasonal desserts. That last covers a lot of territory, as I saw many more items than were listed. The result is that all the service tables are called into play and paved with trays of desserts. The room is so crowded with dining tables, service tables, and hurried personnel that you can't even see all the desserts being offered, let alone make a rational decision. Every time a different table is ready to order cheese or dessert, all the trays are shifted—and it's like those puzzles where you have only one vacant square and have to move all the other around to form the pattern you want. All the waiters were continually engaged in shifting tables, trays, cheese, etc., and none has room to maneuver. We waited a looong time for this cheese tray to make its way down the room to us. David chose Brillat-Savarin, Saint Marcellin, and a blue (shown here), and I had Brillat-Savarin, Saint Marcellin, and Pouligny St. Pierre.

At this point, the timing broke down. The worst thing that can happen during one of these big, multicourse restaurant meals is a long wait between courses. We could feel our blood sugar rising, and our appetities concomitantly waning, as we looked wistfully down the long narrow room to the cheese tray, becalmed at the far end. The restaurant is always booked solid, d demand for tables is high. We're usually among the first to arrive at our restaurants, but some people, just to get in, had chosen dinner hours earlier than they would normally have, and rather earlier than ours. They reached their dessert course while we were still waiting for cheese. The way dessert seems to work there is that they offer you the entire panoply of sweets and let you choose as much or as many as you please. But they don't just bring a tray showing samples or use a trolley. Instead they bring out a full tray of every dessert they make (the menu lists baba au rhum, floating island, shortbread tart of seasonal fruit, fresh fruit salad, Beaujolais style bowl of red fruits, crême brulée, "Gâteau Président Maurice Bernachon," housemade ice creams and sorbets; and seasonal desserts. That last covers a lot of territory, as I saw many more items than were listed. The result is that all the service tables are called into play and paved with trays of desserts. The room is so crowded with dining tables, service tables, and hurried personnel that you can't even see all the desserts being offered, let alone make a rational decision. Every time a different table is ready to order cheese or dessert, all the trays are shifted—and it's like those puzzles where you have only one vacant square and have to move all the other around to form the pattern you want. All the waiters were continually engaged in shifting tables, trays, cheese, etc., and none has room to maneuver. We waited a looong time for this cheese tray to make its way down the room to us. David chose Brillat-Savarin, Saint Marcellin, and a blue (shown here), and I had Brillat-Savarin, Saint Marcellin, and Pouligny St. Pierre.

Next, during the looong wait for the desserts to migrate our way, while the heat continued to rise in the room, we were served a predessert of a little pot of chocolate cream so thick, rich, and intensely chocolate that I couldn't eat more than a couple of small spoonfuls, especially right after all that cheese.

Next, during the looong wait for the desserts to migrate our way, while the heat continued to rise in the room, we were served a predessert of a little pot of chocolate cream so thick, rich, and intensely chocolate that I couldn't eat more than a couple of small spoonfuls, especially right after all that cheese.

When the dessert waiter finally turned his attention to us, I couldn't face anything sticky sweet, starchy, or chocolate, and definitely nothing hot. He was really disappointed when I just asked for some strawberries and talked me into having at least some housemade vanilla ice cream with them, and of course, he made little decorative designs in the sauce.

When the dessert waiter finally turned his attention to us, I couldn't face anything sticky sweet, starchy, or chocolate, and definitely nothing hot. He was really disappointed when I just asked for some strawberries and talked me into having at least some housemade vanilla ice cream with them, and of course, he made little decorative designs in the sauce.

Here's the door man, late in the evening, when he came into the dining room to help with the ushering of parties that had finished eating (all the waiters were shifting desserts). At the right is the photo of us he took outside the door as we left (with the smaller of the lighted letters).

Here's the door man, late in the evening, when he came into the dining room to help with the ushering of parties that had finished eating (all the waiters were shifting desserts). At the right is the photo of us he took outside the door as we left (with the smaller of the lighted letters). We asked the waiter afterward whether Bocuse is often in the restaraunt and whether he often comes into the dining room. He replied, with obvious affection, that Bocuse lives above the restaurant and travels very seldom. He doesn't usually work in the kitchen during meals, but every lunchtime and every dinnertime, he suits up in his crisp chef's whites, dons his tall toque, and comes downstairs to visit with the diners and pose for photos.

We asked the waiter afterward whether Bocuse is often in the restaraunt and whether he often comes into the dining room. He replied, with obvious affection, that Bocuse lives above the restaurant and travels very seldom. He doesn't usually work in the kitchen during meals, but every lunchtime and every dinnertime, he suits up in his crisp chef's whites, dons his tall toque, and comes downstairs to visit with the diners and pose for photos.