Saturday, 31 May 2014: Perpignan to Carcassonne, through the defile

Written 13 June

We got up promptly, intending to head for Carcassonne first thing, but while we were downstairs having breakfast, the elevator quit. While David finished his eating, I left my computer and Kindle with him and walked up five flights to put on my shoes and fetch my purse and the card for Françoise, then walked down again and went out to the post office, where I mailed the card (the only odd-sized one that wouldn't fit in the prepaid international envelopes I usually use) and acquired 20 more international envelopes. On the way back, I found a magnificent (well, gaudy, but very informative) illustrated menu outside a tapas restaurant. Its six seven-foot-high panels listed every kind of tapas I'd ever heard of, and many I hadn't, together with a full-color photo of each and its name in Spanish and in French. I paused to photograph the whole thing, for use as a sort of dictionary of tapas dishes. Now I know what "patatas bravas," "escalivada," "carrillada de cerdo" are! Wonderful!

Shortly after I got back to the hotel, as we were preparing to climb the stairs again, the elevator came back to life, so we packed up the car and headed for Carcassonne, setting the GPS in turn for Estagel, Quillan, and Carcassonne to avoid being taken by the freeway. I had the opportunity along the way to get my obligatory annual photo of a piece of farm equipment holding up traffic. I never spotted anything in this line striking as the vine-straddling tractors of Bugundy; this one would clearly have to fit between the vines. Note the radar-readout to the right of it, showing that we are rolling at 15 km/h and wishing us a good trip. In some of the town, the display alternates between your speed and either a smiley or a frowny face, depending on whether you're staying under the limit.

The roads were good and and extremely scenic, but as you can see from the photo at the right, we were approaching some pretty rocky country, the fringes of the Pyrenees.

As you can also see, considerable dynamite was involved in the road's construction—just another example of the sort of trouble and expense the French so often go to for infrastructure.

As you can also see, considerable dynamite was involved in the road's construction—just another example of the sort of trouble and expense the French so often go to for infrastructure.

We climbed steadily, paralleling the Aude River (for which the département is named) through its gorge, and often along roadways cut into the side of the mountain or even through it. I'm not sure whether you'd call that arch at the right an exaggerated overhang or a short tunnel!

This particularly narrow and heavily engineered route leads through the "Défilé de Pierre-Lys" (the Pierre-Lys defile), and I was astonished to learn that the work that pushed the original road through was undertaken by an abbott of the region, and that it was in the 18th century! The work was interrupted by the French revolution but was resumed and completed afterward.

This particularly narrow and heavily engineered route leads through the "Défilé de Pierre-Lys" (the Pierre-Lys defile), and I was astonished to learn that the work that pushed the original road through was undertaken by an abbott of the region, and that it was in the 18th century! The work was interrupted by the French revolution but was resumed and completed afterward.

The railroad passes through it as well and was inaugurated in May of 1904.

On the other side, the town of Limoux was conveniently located for a lunch stop, so we pulled in there. As usual, parking in the middle of town was hopeless, but the business district was fringed with parking lots along the main highway, which circles around the town. We left the car there and walked into the middle, looking for a likely restaurant.

We found La Carabène, which it seems has considerably pretensions as a serious restaurant in the evening, but we just took advantage of its lunchtime salad offerings. A "carabène" is a sort of decorative staff used in the festivities of the Mardi Gras carnival. They start out as reeds, which carnival krews collect, clean and straighten carefully, and decorate with ribbons and plumes. That's a cluster of some smallish ones in the vase behind David, who's studying the menu.

David chose the salade Haute Vallé, which included toasts with goat cheese drizzled with honey, duck ham, and a mandarine-passionfruit vinaigrette.

David chose the salade Haute Vallé, which included toasts with goat cheese drizzled with honey, duck ham, and a mandarine-passionfruit vinaigrette.

I had the salad Limouxine (I had to ask how to pronounce it, as "x" can be pretty unpredictable in French names; in this case, it kept its "x" sound, "lee-mook-seen"), which was topped with strips of sautéed fresh duck breast, a slab of foie gras, and confit gizzards and dressed with a raspberry vinaigrette.

When we emerged from the restaurant, on the way back to our car, we came across this gorgeous vehicle parked in the square. It's a Delahaye (according to the inscription on the hood ornament) and was absolutely immaculate. As we looked it over, a passerby complimented us on it; we hastened to deny ownership, and the three of us proceeded to examine it at leisure.

When we emerged from the restaurant, on the way back to our car, we came across this gorgeous vehicle parked in the square. It's a Delahaye (according to the inscription on the hood ornament) and was absolutely immaculate. As we looked it over, a passerby complimented us on it; we hastened to deny ownership, and the three of us proceeded to examine it at leisure.

Attached to its front bumper with cable ties was a little plastic plaque that read "Folle échappée du Muguet en Pays Cathars, 29-30-31 mai et 1 juin 2014" (Mad Escape of the Lily of the Valley in Cathar Country, 29-30-21 May and 1 June 2014). We concluded that it was there for a classic-car rally. I'm not sure what the lily of the valley has to do with it, as it's on 1 May, not 1 June, that the French exchange sprigs of lily of the valley, but it did serve to explain the several little cortèges of classic Triumph sports cars we'd encountered on the roads in the previous few days.

Over lunch we'd studied the Michelin green guide to see what else we might do in Limoux and were pleased to find a listing for a museum and audiovisual presentation called "Catharama." The waitress had never heard of it, but she produced a map that showed that its street was quite near where we'd parked the car. So we hiked back up there, hoping to attend the 2 p.m. show, to find that the address was in fact right across the main road from our parking spot. Unfortunately, the building is now occupied by a martial-arts studio. We should learn not to try to travel with a six-year-old green guide.

Onward to Carcassonne, then. For once, our hotel there, an Ibis, was eminently accessible. It was located on the large, open Square Gambetta, located on a flat spot on the banks of the Aude between the tall butte that holds the "Cité (the Medieval walled citadel) and the "Bastide St. Louis," the slightly later walled town down in the valley. Bastides are characterized by their rectilinear streets and their generally rectangular shape, although this one is six-sided as a result of the constraints of the site. The Square Gambetta functions as a large, easily negotiated rotary, and the space under the square itself is a vast parking garage.

Of course, we headed straight for the Office de Tourisme (the one in the bastide; there's another in the cité) and signed up for the deluxe 2.5-hour walking tour of both the cité and the bastide for the following morning. That left us a little time before resting our feet for the walk to dinner, so we stopped into the local museum of fine arts, which is free. The permanent collection was pretty good. I was especially struck by this larger-than-life bust of Philippe François Nazaire Fabre d'Églantine (1750–1794), a French actor, dramatist, poet, and politician of the French Revolution who was born in Carcassonne (and died by the guillotine).

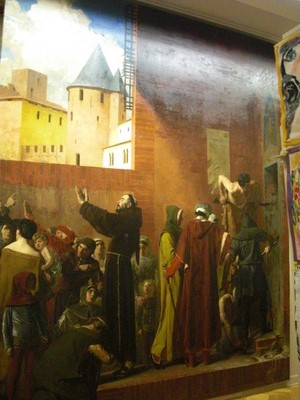

Also striking was this painting by Jean-Paul Laurens (1838–1921) of Bernard Délicieux (great name; it means "delicious"!), a Franciscan prior, haranguing the crowds in Carcassonne in opposition to the Inquisition, which he claimed was inventing false evidence for use against accused Cathars. The guys behind him are using crowbars to attack the wall of the prison in which the accused are confined. He got away with it on this occasion, but a few years later he was haled before the Inquisition himself and sentence to bread, water, and solitary confinement for life. Somebody eventually pleaded his age and frailty and got him out, but he died shortly thereafter.

The collection included several really nice still lives of the "fruit and flowers" kind we like so much, but the lighting was not terrific. I couldn't get good shots of them without big flares from the reflected overhead lights.

Another painting I loved. by Paul Emile Boutigny (1854–1929) was of a scene from a short story by Guy de Maupassant called Boule de Suif (variously translated as Ball of Lard, Butterball, Suet Dumpling; the nickname of the main character). It shows a stage coach at a halt on the road in a snowy city. You can easily Google up a better image than mine by searching on "Boutigny Boule de Suif" (without the quotes).

In a separate, smaller wing across the landing from the permanent collection was a temporary exhibition of the collection of Cérès Franco that featured the sort of art that looks as though kindergarten children were taught how to make papier maché and invited to create brightly painted mythical creatures, except that the pieces were a good deal larger than the children would have made—two to four feet high. On the walls were paintings in the same vein. I don't mean to denigrate them as art—some of the images were very evocative—but they were not our kind of thing at all.

On the way back to the hotel, I managed to get this shot of one of the tall shapes that decorated the square. They were made of woven twigs and sticks and stood maybe 15–20 feet high and were much less dense and substantial than, e.g., the branch-and-twig structures built by Patrick Dougherty; I never found a label on any of them. Some of them had openings near the top that made them evocative of tall robed and hooded women.

Dinner was at Le Parc de Fanck Putelat, a GM four-toque. We chose the "Emotion" menu, so we ate all the same things. The first of three amuse-bouches (or perhaps the first of two bread services) was billed as an olive-oil tasting. We were served a dish that formed two shallow troughs. In one trough was a loaf of bread in the "épi" (wheat ear) shape, and in the other a little dish of coarse salt and a long, capped tube of olive oil. We were instructed to pour the oil (a special, particularly tasty one) into the trough and to dip the bread in it. Good, but the bread was tough as all get out. To go with it, we got four tiny green-olive-studded madeleines.

Dinner was at Le Parc de Fanck Putelat, a GM four-toque. We chose the "Emotion" menu, so we ate all the same things. The first of three amuse-bouches (or perhaps the first of two bread services) was billed as an olive-oil tasting. We were served a dish that formed two shallow troughs. In one trough was a loaf of bread in the "épi" (wheat ear) shape, and in the other a little dish of coarse salt and a long, capped tube of olive oil. We were instructed to pour the oil (a special, particularly tasty one) into the trough and to dip the bread in it. Good, but the bread was tough as all get out. To go with it, we got four tiny green-olive-studded madeleines.

We were also instructed that the round sheets of interlocked metal rings by our place settings (one is visible to the left of the dish of salt) were our bread plates. Odd concept, as the crumbs, oil, butter, or whatever fell right through onto the tablecloth, and the "plates" kept getting pushed out of shape—they were as flexible as fabric, and the links could be squinched together into a solid mass or spread into a coarse mesh. I guess a quintessentially Medieval city requires chain-mail dishes.

The second amuse-bouche was threefold: for each of us, a warm cromesqui (a sort of croquette) of boneless pig's foot topped with mustard, a cube of raw salmon on a little wooden paddle topped with cream and dill, and a shred of pistachio sponge cake topped with a dab of foie gras and chopped pistachios. All delicious.

Also appropriate to a stone-walled city was a stone flatware station. Each of us had one of these oval rocks. As the flatware for each course was brought to us, it was placed on the stone; the spoon is resting in a little crescent-shaped groove designed to receive it. Forks were placed face down with the ends of their tines in the row of four little dimples, and knives were stood on edge with their blades in the little central groove.

Also appropriate to a stone-walled city was a stone flatware station. Each of us had one of these oval rocks. As the flatware for each course was brought to us, it was placed on the stone; the spoon is resting in a little crescent-shaped groove designed to receive it. Forks were placed face down with the ends of their tines in the row of four little dimples, and knives were stood on edge with their blades in the little central groove.

The dining room was furnished with two of these glass fire boxes. The photo cuts off a little of the upper edges, but each was a tall glass rectangle in the bottom center of which flickered a gas flame and on top of which the containers of bread were placed, presumably to keep the bread warm.

To go with the bread (in addition to the épi, we were offered four kinds at intervals throughout the meal), we were brought another rock, this one topped with two cakes of butter, one salted and the other flavored with piments d'Espelette, each with its own wooden spreader.

To go with the bread (in addition to the épi, we were offered four kinds at intervals throughout the meal), we were brought another rock, this one topped with two cakes of butter, one salted and the other flavored with piments d'Espelette, each with its own wooden spreader.

Third amuse-bouche: a bowl of cold piperade; its smooth liquid surface conceals coarsely chopped roasted peppers, tomatoes, and bits of ham. The surface was drizzled with olive oil, and the little black cubes are croutons made of squid-ink bread. Excellent.

First course: white asparagus. The stalks of white asparagus spears had been cut crosswise into circles and laid on edge in a circle filled with delicate asparagus custard (and one whole spear laid alongside). That was topped with a ring of thin, crisply squid-ink bread, an egg yolk poached in olive oil, and bits of smoked haddock alternating with bits of lemon flesh decorated with bits of chervil leaf. At the table, the waiter poured cold cream of asparagus soup around it. Definitely the best treatment of white asparagus of the whole trip (and we had many).

First course: white asparagus. The stalks of white asparagus spears had been cut crosswise into circles and laid on edge in a circle filled with delicate asparagus custard (and one whole spear laid alongside). That was topped with a ring of thin, crisply squid-ink bread, an egg yolk poached in olive oil, and bits of smoked haddock alternating with bits of lemon flesh decorated with bits of chervil leaf. At the table, the waiter poured cold cream of asparagus soup around it. Definitely the best treatment of white asparagus of the whole trip (and we had many).

Second course: soup. Cockles, razor clams, and cubes of foie gras with fresh herbs and lemon "albedo" (which turned out to be a band of lemon sauce around the edge of the dish). Something that looked like a whitish foam was in the center of the dish when it was brought to the table; that melted into the soup when the hot citrus-flavored broth was poured on by the waiter. I assume that was what the menu described as "ephemeral foie gras." The whole thing was terrific!

Third course: lamb. The boned rack was roasted and flavored with Japanese black garlic (garlic cured in some fashion in seawater, which turns it black). On the side, little squiggles of mashed "mitraille" potatoes, baby favas stewed with chorizo, and cubes of braised lamb belly. Very yummy.

Third course: lamb. The boned rack was roasted and flavored with Japanese black garlic (garlic cured in some fashion in seawater, which turns it black). On the side, little squiggles of mashed "mitraille" potatoes, baby favas stewed with chorizo, and cubes of braised lamb belly. Very yummy.

The mignardises were served before dessert, but first, of course, the bread service must be cleared, and I was very interested to see how the chain mail would be handled. Easily, as it happened. The waiter came out with his handy crumb scraper, swept crumbs, bread, and bread plates alike right off the edge of the table into his crumb plate, and carried them away.

The mignardises were served before dessert, but first, of course, the bread service must be cleared, and I was very interested to see how the chain mail would be handled. Easily, as it happened. The waiter came out with his handy crumb scraper, swept crumbs, bread, and bread plates alike right off the edge of the table into his crumb plate, and carried them away.

Dessert: rhubarb. A hazelnut cookie was topped with rhubarb poached in vanilla-anise syrup, cubes of the gelled syrup, a quenelle of (outstanding) blood-orange sorbet, and batons of meringue with anise seeds embedded in them. Excellent.

Dessert: rhubarb. A hazelnut cookie was topped with rhubarb poached in vanilla-anise syrup, cubes of the gelled syrup, a quenelle of (outstanding) blood-orange sorbet, and batons of meringue with anise seeds embedded in them. Excellent.

On the walk back, we paused on the Vieux Pont (the old bridge), now reserved for pedestrians, and I got this not-half-bad photo of the cité, lit up for the night. The French may struggle with shower design, but they really, really know how to light buildings.