Wednesday, 4 June 2014: Castres to Albi, Goya and Jean Jaurès

Written 16 June

We chose Castres for its good restaurant and for its Goya museum, but it turned out to have more to offer. For starters, right across the Agout River from our hotel was this row of historic houses. Historically, Castres was a center for leather working, and these buildings were designed for the trade. Each one had a river-front loading dock entered through a stone archway on the water. The "wetter" processes, like tanning, were carried out on the lower floors, where the river supplied the necessary water, and successively drier processes, like preparation of parchement were carried out on successsively higher floors. Unfortunately, we had no time to explore, beyond reading the guidebook and the occasional posted information panel. I'm not sure we ever did get to the Office de Tourisme, because the stuff we already knew about and the stuff we discovered in the course of the day filled all our time there.

We chose Castres for its good restaurant and for its Goya museum, but it turned out to have more to offer. For starters, right across the Agout River from our hotel was this row of historic houses. Historically, Castres was a center for leather working, and these buildings were designed for the trade. Each one had a river-front loading dock entered through a stone archway on the water. The "wetter" processes, like tanning, were carried out on the lower floors, where the river supplied the necessary water, and successively drier processes, like preparation of parchement were carried out on successsively higher floors. Unfortunately, we had no time to explore, beyond reading the guidebook and the occasional posted information panel. I'm not sure we ever did get to the Office de Tourisme, because the stuff we already knew about and the stuff we discovered in the course of the day filled all our time there.

Another fun discovery was that the local rugby team, Castres Olympique, or "C.O." as it was referred to all over town, was the defending national champion of France and had important matches coming up, so the town was festooned with blue and white banners. Every shop window (including our restaurant of the night before) sported at least a "Go C.O." sticker, and some went all out—like this pharmacy window with a team photo, "Pierre Fabre" jersey autographed by the whole team, championship banners, blue and white balloons, a miniature team rugby ball, and that most un-French item, a blue and white C.O. bill cap. Until his death a little less than a year ago, Fabre was the (very popular) owner of the team and founder of a multinational pharmaceutical group. Apparently rugby has been big around here for quite a while—the team celebrated its hundredth season in 2006.

The Goya Museum is in an annex of the mayor's office and was excellent. It actually contains very little Goya but quite a lot else of interest. I loved this cute little bronze (perhaps a foot long) of a faun chasing a squirrel.

The Goya Museum is in an annex of the mayor's office and was excellent. It actually contains very little Goya but quite a lot else of interest. I loved this cute little bronze (perhaps a foot long) of a faun chasing a squirrel.

I also really liked this large-format oil by Carlos Vázquez y Úbeda of Don Quixote meeting a troup of traveling players. I don't remember the indicent, but it's been a long time since I read the book, and I was pretty young at the time (maybe it's time for a reread?). The painting is undated, but the artist died in 1944.

The two most striking works by Goya himself were this wonderful self-portrait and a huge (more than 3 x 4 meters) 1815 painting of the assembly of the royal company of the Philippines. A detail of the latter was being copied by an artist whose rolling easel was placed directly in front of it. Every time anyone else entered the room, he immediately trundled his work off the side, so as not to obscure the view. I asked whether he intended to copy the whole thing, but he said he wouldn't have time. He was only in town for a few days and was copying only chosen details from paintings in the museum. I was very interested to compare his work with the original, but he insisted I should really spend all my time on the original.

The two most striking works by Goya himself were this wonderful self-portrait and a huge (more than 3 x 4 meters) 1815 painting of the assembly of the royal company of the Philippines. A detail of the latter was being copied by an artist whose rolling easel was placed directly in front of it. Every time anyone else entered the room, he immediately trundled his work off the side, so as not to obscure the view. I asked whether he intended to copy the whole thing, but he said he wouldn't have time. He was only in town for a few days and was copying only chosen details from paintings in the museum. I was very interested to compare his work with the original, but he insisted I should really spend all my time on the original.

We also found a few works by other artists we recognized. They had one by Fantin-Latour, but not one of his floral still lives, which I love. In fact, they had only a few still lives, and they tended to portray not fruit and flowers but cabbage and mutton chops. Perhaps the most famous was this "bust of a man writing" by Picasso.

The museum had other sections, besides painting, including some magnificent desks, of the sort with 57 drawers, not counting the concealed ones, and of all things a large collection of antique fire arms. The latter was all in one room, about 1/3 of which is shown at the left, but many of the details were fascinating, like the tiny "vertical" revolver with a side crank at the right. Many of the tinier ones weren't even "gun shaped."

The museum had other sections, besides painting, including some magnificent desks, of the sort with 57 drawers, not counting the concealed ones, and of all things a large collection of antique fire arms. The latter was all in one room, about 1/3 of which is shown at the left, but many of the details were fascinating, like the tiny "vertical" revolver with a side crank at the right. Many of the tinier ones weren't even "gun shaped."

I had to look on the internet later to learn what made a gun a "poivrière" (which ought to mean a feminine pepperer)—it's a revolver in which each bullet has its own barrel, so rather than just the chambers rotating (as in the classic Western six-shooter) while the barrel and handles remained in place, everything forward of the lock rotates, chambers, barrels, and all, like a small hand-held Gattling gun.

Something I very nearly overlooked was this wonderful blue-and-white frieze, high overhead, around the top of one of the rooms in the museum. It protrayed local individuals (mostly 17th century, and including several women) and groups and listed their civic contributions—e.g., Pierre Borel, local botany; LaBauve d'Arifat, plant nursery of Béziers; Bayard de Ferrières, sheep flock improvement; Henri de Rohan, abalones in the public promenade (I don't understand that one; "ormeaux" must mean something else besides abalones); the Benedictines, agricultural science; Adelaide de Burlats, protection of farmers; Cardaillac Bieule de Caix, water use.

Something I very nearly overlooked was this wonderful blue-and-white frieze, high overhead, around the top of one of the rooms in the museum. It protrayed local individuals (mostly 17th century, and including several women) and groups and listed their civic contributions—e.g., Pierre Borel, local botany; LaBauve d'Arifat, plant nursery of Béziers; Bayard de Ferrières, sheep flock improvement; Henri de Rohan, abalones in the public promenade (I don't understand that one; "ormeaux" must mean something else besides abalones); the Benedictines, agricultural science; Adelaide de Burlats, protection of farmers; Cardaillac Bieule de Caix, water use.

Behind the building was the Mayor's Garden, notable enough to be mentioned in the Michelin Guide. As usual when we visit gardens, it had just been replanted for the summer season, so the flower beds were still pretty young; they'll be resplendent in July and August.

Strolling back toward the middle of things in search of lunch, we passed this weir in the river, just downstream of the leather-working houses I talked about above. Because it was not accompanied by a lock, I conclude that all that incipient leather to be delivered to the riverfront loading docs arrived from upstream (although I suppose a disused lock might have been destroyed during installation of a more modern weir. David spent a little time explaining to me, in terms of fluid dynamics, why the weir was V-shaped. Meanwhile, ducks were moving downstream. They would swim up to the edge, slide down the smooth water, then fly to the bottom when they came to the white part.

Strolling back toward the middle of things in search of lunch, we passed this weir in the river, just downstream of the leather-working houses I talked about above. Because it was not accompanied by a lock, I conclude that all that incipient leather to be delivered to the riverfront loading docs arrived from upstream (although I suppose a disused lock might have been destroyed during installation of a more modern weir. David spent a little time explaining to me, in terms of fluid dynamics, why the weir was V-shaped. Meanwhile, ducks were moving downstream. They would swim up to the edge, slide down the smooth water, then fly to the bottom when they came to the white part.

On the way to lunch, we passed this monumental statue of Jean Jaurès (1859–1914), who was born and raised here. He's one of those French politicians/statesmen who has a street and/or square named for him in every French town large enough to merit the name. Castres turned out to have a museum dedicated just to him, so we planned to spend the afternoon getting straight just who he was and what he did.

We had lunch at the "Tendance Thé ou Café Créperie, which overlooks the Place Jean Jaurès, where the statue is. Like all French créperies, it made its savory crêpes, called "galettes," with buckwheat, which David can't digest, so he ordered the "Comtoise" salad: grilled bacon, raw ham, Comté cheese, and apples.

We had lunch at the "Tendance Thé ou Café Créperie, which overlooks the Place Jean Jaurès, where the statue is. Like all French créperies, it made its savory crêpes, called "galettes," with buckwheat, which David can't digest, so he ordered the "Comtoise" salad: grilled bacon, raw ham, Comté cheese, and apples.

I had a "complete" galette: raw ham, stewed onions, Emmenthal cheese, and an egg, which they topped with grilled bacon for good measure.

Waiting for the museum to open after lunch, David had a decaf and I had ice cream: coffee and violet.

Waiting for the museum to open after lunch, David had a decaf and I had ice cream: coffee and violet.

The museum, just a block or so off the square, was again mostly text, detailing Jaurès's life and politics, initially "opportunist republican," then antimilitarist and socialist. He was a fiery and renowned orator, as shown in the sketches at the right, done by a political cartoonist of his day. You can always recognize him in images and statues because of his beefy build and his beard, which we work forked into two rounded lobes.

A couple of quotes are (in my translations) "A little internationalism leads away from patriotism, but a lot of leads back to it; a little patriotism leads away from internationalism, but a lot leads back to it" and "All progress comes from thought, and we must first give the workers the time and strength to think."

He tried hard to avert WWI through diplomatic means but was assassinated in July of 1914 (a plaque marks the spot in Paris) and is sometimes called the first casualty of the war. The assassin walked up and fired two shots in through a café window in front of multiple witnesses but was, for some reason, later acquitted. He had to leave France for his own safety and was later killed by Spanish revolutionaries.

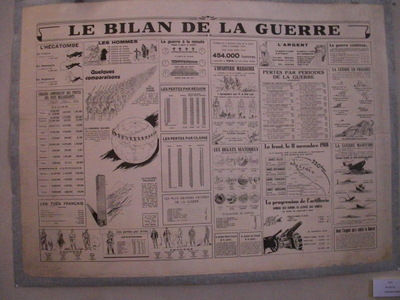

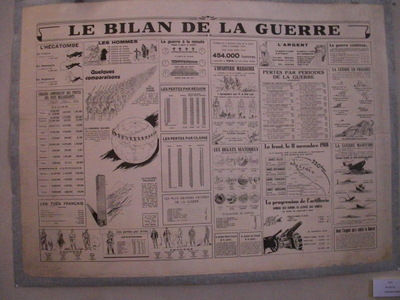

Interesting as the Jaurès museum was, the temporary exhibition was even more so. It was entitled "Posters in Wartime" and consisted of a very large collection of posters from WWI and WWII. The shown one at the left is called "The Balance Sheet of War," and it presents an amazing summary of statistics: the money spent, the length of the front, the progression of the artillery, the ships lost, the material damages, amnd finally the people killed and injured, broken down by period of the war, region, nationality, social class, arm of the military, and numbers killed by the minute, the hour, and the day. Pretty stunning.

Interesting as the Jaurès museum was, the temporary exhibition was even more so. It was entitled "Posters in Wartime" and consisted of a very large collection of posters from WWI and WWII. The shown one at the left is called "The Balance Sheet of War," and it presents an amazing summary of statistics: the money spent, the length of the front, the progression of the artillery, the ships lost, the material damages, amnd finally the people killed and injured, broken down by period of the war, region, nationality, social class, arm of the military, and numbers killed by the minute, the hour, and the day. Pretty stunning.

The one at the right shows a swastica being torn apart by hands sporting the colors of the USA, France, Britain, and Russia. Others, now shown here, advertised everything from a fund to help veterans with tuberculosis, to recruitment of French youth to a sort of counterpart of the Hitler youth, to organizations to make sure enlisted men got their due after the war, to the proper behavior in response to air-raid sirens (and what to do if the exit from the air-raid shelter was blocked by debris), to the German-imposed curfew rules for French cities, to fund-raising (in English of course) to help the war horses, to a campaign to get mothers, sisters, and wives to encourage their men to enlist.

Not all the posters were from the allied side. Some were promulgated by the Germans, like the curfew regulations. Others were from occupied France and the Vichy government.

Not all the posters were from the allied side. Some were promulgated by the Germans, like the curfew regulations. Others were from occupied France and the Vichy government.

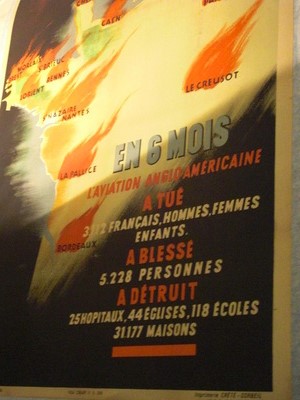

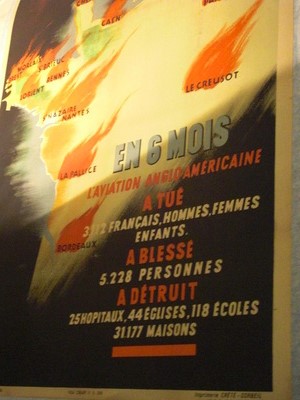

The one at the left here says, "In six months, Anglo-American aviation as killed 3112 French men, women, and children, wounded 5228 people, and destroyed 25 hospitals, 44 churches, 118 schools, and 31,177 houses."

The one at the right, from the Vichy government, which shows France being attacked by three wolves/dogs (Free-Masonry, the Jews, and De Gaulle) and a three-headed snake ("lies") says "Leave us alone!"

Another advertised for French workers to go fill jobs in Germany, emphasizing that they would have the chance to spread the word and demonstration of French excellence.

The posters occupied the whole temporary exhibition space on the main floor of the museum, then continued up several flights of stairs, occupying the tall walls in the stairwell, and finally took all of a conference room on the top floor. Most the posters were just presented to speak for themselves, but occasional explanatory panels pointed out techniques used to add emotional appeal, like all "new start" symbolism in the "Leave us alone" poster, with its sunrise and planting a new sprout. Very effective exhibition.

By the time we finished the museum, it was getting late, so we retrieved our luggage from thehotel and the car from its underground garage and drove the short distance on to Albi. The garage was actually only partly underground. It was below street level but open at the side. The river bank was steep on that side (opposite the leatherworking houses), so they built a parking garage into it and ran the river-side boulevard and a broad sidewalk across the top of it. If you stood on one of the balconies of a leatherworking house and looked across the river, you'd see three layers of cars, then, on top, the street and our hotel.

On the way, we saw, for the first time, a couple of fields of onions, one field of very young corn, and maybe a field of very young sunflowers. All the rest was grain or pasture/hay; no grapes.

Our restaurant for the evening was "L'Esprit du Vin," and it had no menu as such. You chose among three levels of surprise menu, from 75 euros to 105 euros without wines (100 to 138 with wine pairings; 55 euros for vegetarian), specified your allergies and dislikes, and hoped for the best. We chose the middle menu, at 85 euros.

Our restaurant for the evening was "L'Esprit du Vin," and it had no menu as such. You chose among three levels of surprise menu, from 75 euros to 105 euros without wines (100 to 138 with wine pairings; 55 euros for vegetarian), specified your allergies and dislikes, and hoped for the best. We chose the middle menu, at 85 euros.

First, amuse-bouche: Left to right, basil cookies topped with mousseline of salmon (and one salmon egg each), sesame waffle cones filled with eggplant caviare and one sprat each (in French usage, a sprat is a smoked anchovy; the cones are standing in a bowl filled with coarse bright-orange salt), black black olive macaroons topped with tapenade, and a little dish of green olives deep-fried in a Parmesan crust. All very good, though the fried olives were the best. By the way, the sprouts on top of the salmon mousseline—those are atsina cress.

In the background, you can see the trough in which they brought our bread assortment and a crock of bright-orange sobressada butter (butter puréwith a kind of Corsican sausage).

Second amuse-bouche: "Lacquered" lentils, carrots, a timball of foie gras and salmon tartare with diced apple and chives, a Petrossian rye crisp; dabs of cooked oyster cream (all but one hidden by the crisp), each topped with a tiny marigold flower dabs with tiny marigold flower (perhaps actually a Mexican tarragon flower; Mexican tarragon is a composite). The whole thing is garnished with a large "oyster leaf," a leaf that tastes, on first bite, just like a raw oyster. Unfortunately, I had a very bad experience with one a few years ago; the taste lingered and lingered in the mouth, slowly changing, growing more and more distasteful and spoiling the next three courses. I only got rid of it finally with a lot of Crest and energetic brushing. I shoved mine aside and warned David to do the same. The rest was delicious.

First course: A sort of two-fer. On the plate is a roasted langoustine tail on a bed of asparatus and morels, garished with a nasturtium flower and dots of asparagus mustard. In a separate footed glass (shown at right) was a smoked morel risotto. It arrived topped with a saucer (which was holding in the beech-wood smoke over the risotto) in turn topped with an egg cup holding another of those very fragile, barely cooked low-temperature eggs, in its shell with the top cut off.

First course: A sort of two-fer. On the plate is a roasted langoustine tail on a bed of asparatus and morels, garished with a nasturtium flower and dots of asparagus mustard. In a separate footed glass (shown at right) was a smoked morel risotto. It arrived topped with a saucer (which was holding in the beech-wood smoke over the risotto) in turn topped with an egg cup holding another of those very fragile, barely cooked low-temperature eggs, in its shell with the top cut off.

The idea was to remove the saucer, dump the egg from its shell into the risotto, and to stir it in thoroughly. Then you were supposed to eat the risotto during or after eating the langoustine. The view at the right shows the egg dumped in but not yet stirred in. All very delicious, except that around here they make their risottos a little more al dente than I prefer.

Second course: A thick slab of seared tuna. In front of it, the little brown football is a braised squash blossom stuffed with piperade. Behind it, you can just see the rim of a little abalone shell, which was filled with cockles, mussels, and razor clams baked under a basil crust. The orange ball to the side of it is a cromesqui filled with hot, liquid aioli; we were warned not to try to bit into it, as it was very hot and would splatter. Around the edge of the plate, some sprigs of wild asparagus. Finally, under the tuna was a heap of cooked greens that I couldn't identify. The waitress said it was what sounded like "asthère maritime," also called "corne de cerf" (stag's horn). It took considerable negoiation with Google to get images of anything other than staghorn ferns, but I finally found it. It's Plantago coronopus, the stag's horn plantain, a hardy (and tasty) beach plant; I still haven't figured out the "asthère" part, where the plants French Wikipedia entry does not mention.

Second course: A thick slab of seared tuna. In front of it, the little brown football is a braised squash blossom stuffed with piperade. Behind it, you can just see the rim of a little abalone shell, which was filled with cockles, mussels, and razor clams baked under a basil crust. The orange ball to the side of it is a cromesqui filled with hot, liquid aioli; we were warned not to try to bit into it, as it was very hot and would splatter. Around the edge of the plate, some sprigs of wild asparagus. Finally, under the tuna was a heap of cooked greens that I couldn't identify. The waitress said it was what sounded like "asthère maritime," also called "corne de cerf" (stag's horn). It took considerable negoiation with Google to get images of anything other than staghorn ferns, but I finally found it. It's Plantago coronopus, the stag's horn plantain, a hardy (and tasty) beach plant; I still haven't figured out the "asthère" part, where the plants French Wikipedia entry does not mention.

Third course: Pigeon (raised between Albi and Castres). Much easier to eat than it looks. The part in the center of the plate, on the bed of chanterelles and baby favas, is boneless (except for the tiny leg bone left at the top, for decorative purposes) and stuffed with foie gras. The section on the side of the plate, with the carrot, zucchini, baby leek, stalk of fennel, and purple pea blossom (which has fallen out of its calyx; they all did) is confit, so it came easily away from the bone. Altogether delicious and decorated with rosemary sprig, pea shoot, and little branch of thyme flowers. Best pigeon of the trip.

Predessert: Caramel-cigar ice cream, in a pool of "configure de lait" (dulce de leche), topped with a chocolate square and surrounded by cookie crumbs. Emotionally challenging. It was tasty, but I'm still not sure I approve. The chef actually simmered a cigar with his caramel before making the ice cream. It apparently didn't have enough nicotine in it to upset our stomachs, but I still wouldn't serve it to a child (or order it for myself).

Predessert: Caramel-cigar ice cream, in a pool of "configure de lait" (dulce de leche), topped with a chocolate square and surrounded by cookie crumbs. Emotionally challenging. It was tasty, but I'm still not sure I approve. The chef actually simmered a cigar with his caramel before making the ice cream. It apparently didn't have enough nicotine in it to upset our stomachs, but I still wouldn't serve it to a child (or order it for myself).

Dessert: Pistachio cake with vanilla buttercream, a chewy spiral caramel cookie strip, strawberry-lemon-verbena sorbet, fruit, poached rhubarb batons, atsina cress sprouts, and those sprouts that might be tomato, all bestrewn with elder-berry flowers. Very pretty and appropriately light after all the other courses.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

We chose Castres for its good restaurant and for its Goya museum, but it turned out to have more to offer. For starters, right across the Agout River from our hotel was this row of historic houses. Historically, Castres was a center for leather working, and these buildings were designed for the trade. Each one had a river-front loading dock entered through a stone archway on the water. The "wetter" processes, like tanning, were carried out on the lower floors, where the river supplied the necessary water, and successively drier processes, like preparation of parchement were carried out on successsively higher floors. Unfortunately, we had no time to explore, beyond reading the guidebook and the occasional posted information panel. I'm not sure we ever did get to the Office de Tourisme, because the stuff we already knew about and the stuff we discovered in the course of the day filled all our time there.

We chose Castres for its good restaurant and for its Goya museum, but it turned out to have more to offer. For starters, right across the Agout River from our hotel was this row of historic houses. Historically, Castres was a center for leather working, and these buildings were designed for the trade. Each one had a river-front loading dock entered through a stone archway on the water. The "wetter" processes, like tanning, were carried out on the lower floors, where the river supplied the necessary water, and successively drier processes, like preparation of parchement were carried out on successsively higher floors. Unfortunately, we had no time to explore, beyond reading the guidebook and the occasional posted information panel. I'm not sure we ever did get to the Office de Tourisme, because the stuff we already knew about and the stuff we discovered in the course of the day filled all our time there.

The Goya Museum is in an annex of the mayor's office and was excellent. It actually contains very little Goya but quite a lot else of interest. I loved this cute little bronze (perhaps a foot long) of a faun chasing a squirrel.

The Goya Museum is in an annex of the mayor's office and was excellent. It actually contains very little Goya but quite a lot else of interest. I loved this cute little bronze (perhaps a foot long) of a faun chasing a squirrel.

The two most striking works by Goya himself were this wonderful self-portrait and a huge (more than 3 x 4 meters) 1815 painting of the assembly of the royal company of the Philippines. A detail of the latter was being copied by an artist whose rolling easel was placed directly in front of it. Every time anyone else entered the room, he immediately trundled his work off the side, so as not to obscure the view. I asked whether he intended to copy the whole thing, but he said he wouldn't have time. He was only in town for a few days and was copying only chosen details from paintings in the museum. I was very interested to compare his work with the original, but he insisted I should really spend all my time on the original.

The two most striking works by Goya himself were this wonderful self-portrait and a huge (more than 3 x 4 meters) 1815 painting of the assembly of the royal company of the Philippines. A detail of the latter was being copied by an artist whose rolling easel was placed directly in front of it. Every time anyone else entered the room, he immediately trundled his work off the side, so as not to obscure the view. I asked whether he intended to copy the whole thing, but he said he wouldn't have time. He was only in town for a few days and was copying only chosen details from paintings in the museum. I was very interested to compare his work with the original, but he insisted I should really spend all my time on the original.

The museum had other sections, besides painting, including some magnificent desks, of the sort with 57 drawers, not counting the concealed ones, and of all things a large collection of antique fire arms. The latter was all in one room, about 1/3 of which is shown at the left, but many of the details were fascinating, like the tiny "vertical" revolver with a side crank at the right. Many of the tinier ones weren't even "gun shaped."

The museum had other sections, besides painting, including some magnificent desks, of the sort with 57 drawers, not counting the concealed ones, and of all things a large collection of antique fire arms. The latter was all in one room, about 1/3 of which is shown at the left, but many of the details were fascinating, like the tiny "vertical" revolver with a side crank at the right. Many of the tinier ones weren't even "gun shaped."

Something I very nearly overlooked was this wonderful blue-and-white frieze, high overhead, around the top of one of the rooms in the museum. It protrayed local individuals (mostly 17th century, and including several women) and groups and listed their civic contributions—e.g., Pierre Borel, local botany; LaBauve d'Arifat, plant nursery of Béziers; Bayard de Ferrières, sheep flock improvement; Henri de Rohan, abalones in the public promenade (I don't understand that one; "ormeaux" must mean something else besides abalones); the Benedictines, agricultural science; Adelaide de Burlats, protection of farmers; Cardaillac Bieule de Caix, water use.

Something I very nearly overlooked was this wonderful blue-and-white frieze, high overhead, around the top of one of the rooms in the museum. It protrayed local individuals (mostly 17th century, and including several women) and groups and listed their civic contributions—e.g., Pierre Borel, local botany; LaBauve d'Arifat, plant nursery of Béziers; Bayard de Ferrières, sheep flock improvement; Henri de Rohan, abalones in the public promenade (I don't understand that one; "ormeaux" must mean something else besides abalones); the Benedictines, agricultural science; Adelaide de Burlats, protection of farmers; Cardaillac Bieule de Caix, water use.

Strolling back toward the middle of things in search of lunch, we passed this weir in the river, just downstream of the leather-working houses I talked about above. Because it was not accompanied by a lock, I conclude that all that incipient leather to be delivered to the riverfront loading docs arrived from upstream (although I suppose a disused lock might have been destroyed during installation of a more modern weir. David spent a little time explaining to me, in terms of fluid dynamics, why the weir was V-shaped. Meanwhile, ducks were moving downstream. They would swim up to the edge, slide down the smooth water, then fly to the bottom when they came to the white part.

Strolling back toward the middle of things in search of lunch, we passed this weir in the river, just downstream of the leather-working houses I talked about above. Because it was not accompanied by a lock, I conclude that all that incipient leather to be delivered to the riverfront loading docs arrived from upstream (although I suppose a disused lock might have been destroyed during installation of a more modern weir. David spent a little time explaining to me, in terms of fluid dynamics, why the weir was V-shaped. Meanwhile, ducks were moving downstream. They would swim up to the edge, slide down the smooth water, then fly to the bottom when they came to the white part.

We had lunch at the "Tendance Thé ou Café Créperie, which overlooks the Place Jean Jaurès, where the statue is. Like all French créperies, it made its savory crêpes, called "galettes," with buckwheat, which David can't digest, so he ordered the "Comtoise" salad: grilled bacon, raw ham, Comté cheese, and apples.

We had lunch at the "Tendance Thé ou Café Créperie, which overlooks the Place Jean Jaurès, where the statue is. Like all French créperies, it made its savory crêpes, called "galettes," with buckwheat, which David can't digest, so he ordered the "Comtoise" salad: grilled bacon, raw ham, Comté cheese, and apples.

Waiting for the museum to open after lunch, David had a decaf and I had ice cream: coffee and violet.

Waiting for the museum to open after lunch, David had a decaf and I had ice cream: coffee and violet.

Interesting as the Jaurès museum was, the temporary exhibition was even more so. It was entitled "Posters in Wartime" and consisted of a very large collection of posters from WWI and WWII. The shown one at the left is called "The Balance Sheet of War," and it presents an amazing summary of statistics: the money spent, the length of the front, the progression of the artillery, the ships lost, the material damages, amnd finally the people killed and injured, broken down by period of the war, region, nationality, social class, arm of the military, and numbers killed by the minute, the hour, and the day. Pretty stunning.

Interesting as the Jaurès museum was, the temporary exhibition was even more so. It was entitled "Posters in Wartime" and consisted of a very large collection of posters from WWI and WWII. The shown one at the left is called "The Balance Sheet of War," and it presents an amazing summary of statistics: the money spent, the length of the front, the progression of the artillery, the ships lost, the material damages, amnd finally the people killed and injured, broken down by period of the war, region, nationality, social class, arm of the military, and numbers killed by the minute, the hour, and the day. Pretty stunning.

Not all the posters were from the allied side. Some were promulgated by the Germans, like the curfew regulations. Others were from occupied France and the Vichy government.

Not all the posters were from the allied side. Some were promulgated by the Germans, like the curfew regulations. Others were from occupied France and the Vichy government. Our restaurant for the evening was "L'Esprit du Vin," and it had no menu as such. You chose among three levels of surprise menu, from 75 euros to 105 euros without wines (100 to 138 with wine pairings; 55 euros for vegetarian), specified your allergies and dislikes, and hoped for the best. We chose the middle menu, at 85 euros.

Our restaurant for the evening was "L'Esprit du Vin," and it had no menu as such. You chose among three levels of surprise menu, from 75 euros to 105 euros without wines (100 to 138 with wine pairings; 55 euros for vegetarian), specified your allergies and dislikes, and hoped for the best. We chose the middle menu, at 85 euros.

First course: A sort of two-fer. On the plate is a roasted langoustine tail on a bed of asparatus and morels, garished with a nasturtium flower and dots of asparagus mustard. In a separate footed glass (shown at right) was a smoked morel risotto. It arrived topped with a saucer (which was holding in the beech-wood smoke over the risotto) in turn topped with an egg cup holding another of those very fragile, barely cooked low-temperature eggs, in its shell with the top cut off.

First course: A sort of two-fer. On the plate is a roasted langoustine tail on a bed of asparatus and morels, garished with a nasturtium flower and dots of asparagus mustard. In a separate footed glass (shown at right) was a smoked morel risotto. It arrived topped with a saucer (which was holding in the beech-wood smoke over the risotto) in turn topped with an egg cup holding another of those very fragile, barely cooked low-temperature eggs, in its shell with the top cut off.

Second course: A thick slab of seared tuna. In front of it, the little brown football is a braised squash blossom stuffed with piperade. Behind it, you can just see the rim of a little abalone shell, which was filled with cockles, mussels, and razor clams baked under a basil crust. The orange ball to the side of it is a cromesqui filled with hot, liquid aioli; we were warned not to try to bit into it, as it was very hot and would splatter. Around the edge of the plate, some sprigs of wild asparagus. Finally, under the tuna was a heap of cooked greens that I couldn't identify. The waitress said it was what sounded like "asthère maritime," also called "corne de cerf" (stag's horn). It took considerable negoiation with Google to get images of anything other than staghorn ferns, but I finally found it. It's Plantago coronopus, the stag's horn plantain, a hardy (and tasty) beach plant; I still haven't figured out the "asthère" part, where the plants French Wikipedia entry does not mention.

Second course: A thick slab of seared tuna. In front of it, the little brown football is a braised squash blossom stuffed with piperade. Behind it, you can just see the rim of a little abalone shell, which was filled with cockles, mussels, and razor clams baked under a basil crust. The orange ball to the side of it is a cromesqui filled with hot, liquid aioli; we were warned not to try to bit into it, as it was very hot and would splatter. Around the edge of the plate, some sprigs of wild asparagus. Finally, under the tuna was a heap of cooked greens that I couldn't identify. The waitress said it was what sounded like "asthère maritime," also called "corne de cerf" (stag's horn). It took considerable negoiation with Google to get images of anything other than staghorn ferns, but I finally found it. It's Plantago coronopus, the stag's horn plantain, a hardy (and tasty) beach plant; I still haven't figured out the "asthère" part, where the plants French Wikipedia entry does not mention.

Predessert: Caramel-cigar ice cream, in a pool of "configure de lait" (dulce de leche), topped with a chocolate square and surrounded by cookie crumbs. Emotionally challenging. It was tasty, but I'm still not sure I approve. The chef actually simmered a cigar with his caramel before making the ice cream. It apparently didn't have enough nicotine in it to upset our stomachs, but I still wouldn't serve it to a child (or order it for myself).

Predessert: Caramel-cigar ice cream, in a pool of "configure de lait" (dulce de leche), topped with a chocolate square and surrounded by cookie crumbs. Emotionally challenging. It was tasty, but I'm still not sure I approve. The chef actually simmered a cigar with his caramel before making the ice cream. It apparently didn't have enough nicotine in it to upset our stomachs, but I still wouldn't serve it to a child (or order it for myself).