Saturday, 7 June 2014: Albi to Millau, via Roquefort

Written 17 June

From my point of view, the main differences between an Ibis Budget and a full Ibis are (a) The Ibis Budget gives you little bars of soap, whereas the Ibis makes you make do with shower gel (why do they think this is better?), and (b) the Ibis provides a fuller breakfast buffet, including, e.g., pain au chocolate and Spanish potato tortilla, which I'm fond of. It also includes a bowl of fresh fruit; this one threw in a pineapple, some bananas, grapes, and strawberries, but still no cherries or apricots. It provided more kinds of bread, some pound cake, and non-shrink-wrapped cheese, but nothing very interesting.

Then it was off to Roquefort, which you have to visit on a day-trip because it has no hotel; the village is actually very small. A few miles outside Albi, we encountered our first field of colza (oil-seed rape). We passed a couple of wineries, but no vines, mostly just grain and pasture/hay.

Then it was off to Roquefort, which you have to visit on a day-trip because it has no hotel; the village is actually very small. A few miles outside Albi, we encountered our first field of colza (oil-seed rape). We passed a couple of wineries, but no vines, mostly just grain and pasture/hay.

The photo at the left shows what the terrain was like as we approached Roquefort. Note that the roof of the house beside the road is actually below road level—steep. I had bet David that we would arrive and pass through Roquefort, without seeing one of the sheep that produce the gazillions of gallons of sheeps' milk used by the Roquefort producers. It's my theory that, in France, by law, only the most appealing and charismatic of livestock can be reared within sight of a highway—basically horses and cows, with goats and sheep on the borderline of acceptability; you never, ever see pigs or poultry of any kind from the car. But I lost the bet; we actually saw two flocks of sheep in the course of the day. Untold thousands more must be hidden from view.

We just set the GPS to find the town, reasoning that large signs there would direct us to cheese-tour opportunities. We were right, and having no basis for preferring one over another, we stopped at the first one we came to, the Société company.

We arrived about 11:30 a.m. and signed up for the noon guided tour. The waiting room was well furnished with exhibits and reading material on the subject of cheese, and a television in the corner played a continuous loop of old Roquefort TV commercials.

We arrived about 11:30 a.m. and signed up for the noon guided tour. The waiting room was well furnished with exhibits and reading material on the subject of cheese, and a television in the corner played a continuous loop of old Roquefort TV commercials.

One item on display was this "piqueuse" (pricker). A whole wheel of freshly made sheeps' milk cheese is placed on its little anvil (just behind the label), flat side up, a heap of salt is put on top of the cheese, and the piqueuse then drives a set of spikes straight down through the it, injecting some of the salt but mostly providing for air circulation through the center of the the cheese.

Eventually, our turn came up, and we and a small group of French folks were conducted into the caves to the famous animated earthquake model. The green guide had said to dress warmly, so we'd brought our coats. Just as well, because the caves are kept at 9°C (ca. 48°F) and 95% humidity.

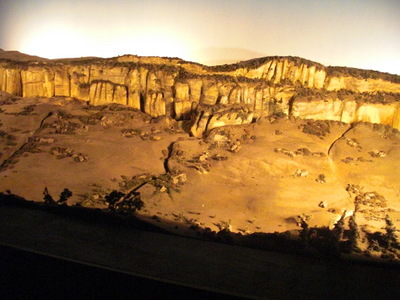

The intial state of the animated model is shown at the right. It's supposed to portray the state of the Roquefort landscape a million years ago, just before a giant earthquake remodeled things.

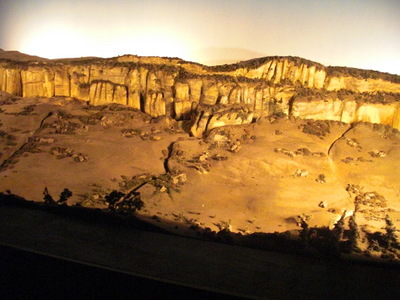

While we watched, lightning flashed, thunder rolled, the earth groaned, and the land began to shift and slide, and that in the foreground sank. At the left is the landscape right after the huge earthquake that created the Roquefort caves.

While we watched, lightning flashed, thunder rolled, the earth groaned, and the land began to shift and slide, and that in the foreground sank. At the left is the landscape right after the huge earthquake that created the Roquefort caves.

Then the lights went out briefly, and when they came back up, the model looked as it's shown on the right (an overlay was lowered on wires from the ceiling, putting the modern village and roads in place).

After the earthquake model, we saw a short film that showed all the steps in the process of producing roquefort, framed as brief, almost wordless visual profiles of individual employees of the company, listing their names, length of time in their jobs, and what they do in the production chain, from shepherds to distribution drivers.

After the earthquake model, we saw a short film that showed all the steps in the process of producing roquefort, framed as brief, almost wordless visual profiles of individual employees of the company, listing their names, length of time in their jobs, and what they do in the production chain, from shepherds to distribution drivers.

Then came a short "son et lumière, projected on the stone walls of the caves; one scene from which is shown at the left. At the right is a glass bottle showing rather a young culture of the centrally important Penicillium roqueforti, just starting to cover its substrate of rye bread. That step is done in the next village over.

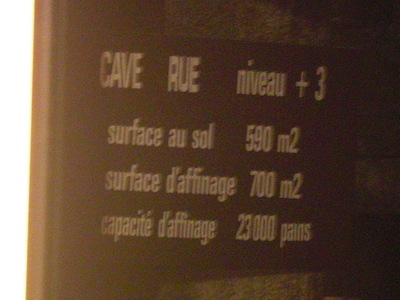

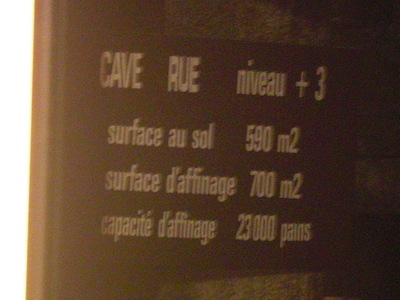

The aging cave we saw most of is called "Rue" (street), simply because, of Société's underground holdings, it's the one nearest the street. Here's its information panel, at the left: floor area, 590 m2; ripening surface (i.e., shelf space for cheeses), 700 m2; ripening capacity, 23,000 loaves (the whole wheels of cheese are called loaves). The cheeses ripened here are of Société's "medium" variety, the one commonly available on the market and the one they produce in by far the largest quantities. In other, smaller, caves, they produce a stronger-flavored and a milder-flavored variety, available only is more specialized shops.

The aging cave we saw most of is called "Rue" (street), simply because, of Société's underground holdings, it's the one nearest the street. Here's its information panel, at the left: floor area, 590 m2; ripening surface (i.e., shelf space for cheeses), 700 m2; ripening capacity, 23,000 loaves (the whole wheels of cheese are called loaves). The cheeses ripened here are of Société's "medium" variety, the one commonly available on the market and the one they produce in by far the largest quantities. In other, smaller, caves, they produce a stronger-flavored and a milder-flavored variety, available only is more specialized shops.

At the right is a rather dark photo of many, many wheels of cheese, each standing on edge and spaced a little away from its neighbors, quietly growing Penicillium. Cheeses spend at least 14 days here (the minimum required for the designation Roquefort) and up to 25 days, depending on the judgement of the cellar master about the development of the color, texture, and aroma. He doesn't actually taste the ripening cheese.

At the end of the tour, just before the tasting, we were led past a whole series of little dioramas portraying historical figures known or thought to enjoy Roquefort, from Pliny the Elder, through Charlemagne, Charles VI, Diderot and D'Alembert (not FSU's D'Alembert; I don't know his taste in cheese), and Casanova.

After that, we had the chance to taste all three varieties (and to purchase them and any of Société's other cheeses as well, of course). The French folks were whipping out their wallets left and right, but buying any would not really have been practical for us. If we'd been staying in an apartment or gîte, with a kitchen, I would have loved to acquire one of the three-packs at the left-hand side of the left-hand photo, containing 1/6 of a wheel of each of the varieties.

After that, we had the chance to taste all three varieties (and to purchase them and any of Société's other cheeses as well, of course). The French folks were whipping out their wallets left and right, but buying any would not really have been practical for us. If we'd been staying in an apartment or gîte, with a kitchen, I would have loved to acquire one of the three-packs at the left-hand side of the left-hand photo, containing 1/6 of a wheel of each of the varieties.

At the right is an assortment of the company's other cheeses. Right now, they're running a surplus of sheeps' milk, so they make some of it into other products, like feta (which they sell mostly as glass jars of herb-marinated cubes, called Salakis, although I understand the Greek feta people have sued them over calling it "feta"), tomme de brebis, etc. In other regions of France, and with other flocks of sheep of the reginally appropriate breeds, they produce Corsica and Petit Basque sheeps' cheeses.

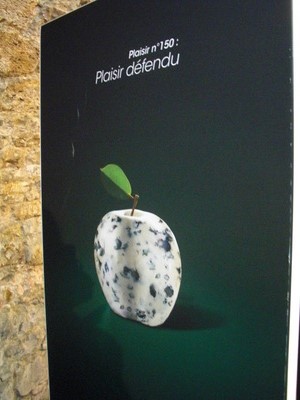

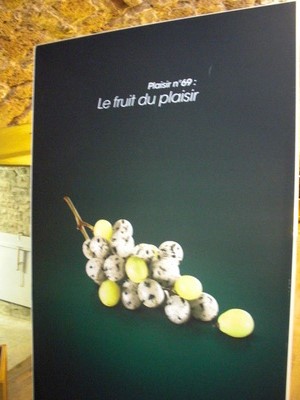

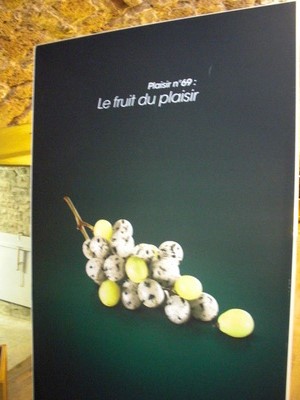

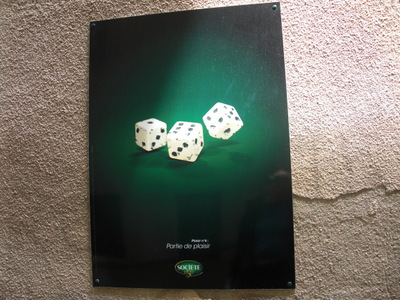

All over the place were posters from current and previous advertising campaigns, including this series of Roquefort carved (or CGI'd) into the shapes of foods it goes well with (and dice; does it go well with gambling games?).

All over the place were posters from current and previous advertising campaigns, including this series of Roquefort carved (or CGI'd) into the shapes of foods it goes well with (and dice; does it go well with gambling games?).

So here's how the cheese-making process works. In a village nearby, bakers produce a special rye bread, which is innoculated with the appropriate

Penicillium roqueforti isolate. The isolates are proprietary; Société uses three, one each for the strong, medium, and mild varieties of cheese; other companies have their own isolates and their own moldy-bread facilities. Once the bread is well and properly moldy, essentially a dry, hollow mass full of mold spores, it is crushed, processed into a powder, and bottled in measured doses (like the one in the red-topped vial in the photo of the partially moldy bread above).

Meanwhile, all over the region (but only within specific, legally defined boundaries), sheep of a specific breed are milked, and the milk is made into cheese, either at the farm or in cooperatives that serve several farms. As each batch of milk (enough for 240 wheels of cheese, I think she said) is poured into the vat for heating and curdling, a dose of

Penicillium is mixed in (one of the little vials mentioned above). The milk is then turned into cheese curds, which are ladeled into molds, drained, and pressed gently until they hold their shape as wheels but are still riddled with little nooks and crannies between the curds. Each wheel weighs 3 kg.

The wheels, still entirely white but laced with

Penicillium spores, are then conveyed to Roquefort (and not just any village of that name, of which France contains many, but specifically Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, the Roquefort; to earn the name, the cheeses must be matured in the caves within a very circumscribed area of the village), to the caves of the company with which the farm is associated, salted, run through the "piqueuse" (which does not inject the mold, as I've heard some say but only aerates the wheel), and then stood on edge, on salted shelves, spaced a little apart, in the appropriate cave. The caves were formed naturally during the giant earthquake, but many have been enlarged, had smooth cement floors poured, etc.

During the ensuing 14 to 25 days, the mold spores develop and produce the blue veining so prominent in Roquefort. The cheeses are not turned, basted, or otherwise fiddled with during that time, but after 14 days, the cellar master starts testing them. He selects one from each batch; uses a coring tool to pull out a sample; feels, smells, and examines the sample; they puts it back in its hole in the cheese.

During the ensuing 14 to 25 days, the mold spores develop and produce the blue veining so prominent in Roquefort. The cheeses are not turned, basted, or otherwise fiddled with during that time, but after 14 days, the cellar master starts testing them. He selects one from each batch; uses a coring tool to pull out a sample; feels, smells, and examines the sample; they puts it back in its hole in the cheese.

The air in the caves is continually renewed through a system of large and small natural cracks and faults called "fleurines." The company has installed doors or shutters on some of them, so that the air flow can be controlled to some extent. For example, on very hot days, the temperature in the caves can rise a few degrees, so the cellar master can use the shutters to shift the air flow a little to keep it from rising too high.

When the judges that the batch has reached the proper stage of development, he sends it on to the wrappers, a battalion of ladies (always ladies) who wrap each wheel in tinfoil—not aluminum foil, but actual tin foil, which is much stronger and which slows development of the mold to a crawl. The company used to employ hundreds of wrappers, but some of the cheeses are machine-wrapped now, so the battalion is down to eight. They were supposed to retire in April, but they're still there, wrapping two cheeses a minute. Our guide demonstrated the technique by wrapping a cheese-shaped cylinder of wood before our eyes. Apparently, the reason the ladies are still wrapping is that some of the cheeses, while standing on their edges, become a little flattened on one side, and the machine can't cope with that. They're working on solutions to the problem.

Once wrapped, the cheeses are further matured for 3–12 months, to allow the flavor to develop, before they are cut and packaged for distribution. The guide emphasized that wheels of Roquefort are never sold whole. They are cut at least in half, to display the characteristic blue veining. The Lake Ella Publix has two brands, Société and Île de France, both in 3.5-oz wedges. We'll have to do a comparative tasting to see which we prefer.

It was after 1 before we finished the tour, and restaurants are few in the tiny town, so for lunch we simply repaired to the company's affiliated restaurant, just above the parking lot. As you might expect, every item on the menu contained roquefort.

It was after 1 before we finished the tour, and restaurants are few in the tiny town, so for lunch we simply repaired to the company's affiliated restaurant, just above the parking lot. As you might expect, every item on the menu contained roquefort.

David chose a salad topped with walnuts, roquefort, and walnuts. I had one that showcased three of Société's cheeses: creamy ripened sheeps' cheese (without mold), roquefort, and cubes of Salakis. Both excellent.

I'm sometimes leery of Roquefort, because it's sometimes way too pungent for me, but this visit proved that, when it's served on the spot, recently certified by the cellar master to be in peak condition, I really like it.

I had hoped also to tour the Papillon caves as well, but if we were to have a chance of reaching MillaU in time to go to the viaduct's visitor center, we wouldn't have time, so we hit the road again.

We found Millau and our hotel easily enough, and spotted the entrance to the visitor's center, under the viaduct, on the way into town. There the simplicity stopped. David double-parked while I ran in to ask the hotel about parking. Sorry, the garage was full. We could try the lot behind the church across the street, but if that was full, we'd just have to find something on the street. Drat. The church lot was full, so we cruised up and down Avenue Jean Jaurès until we finally found a spot several blocks away, then wrestled our luggage over the uneven sidewalks back to the hotel.

While I waited my turn to check in, I got to listen to the conversation, in English, between the desk clerk and the German organizer of a tour group also checking in. Did his group have a system for staggering arrival for breakfast, some earlier and some later? No, they all planned to come down to breakfast at the same time. (Aargh, I thought; the buffet will be stripped.) After some confusion that arose because the organizer didn't know the English word "leave" (when the clerk finally substituted "check out," things went more smoothly), it was our turn. How many in that German group?, I asked. About 100. (Double aargh!) But, as it turned out, the group had entirely overflowed the Ibis Budget, so we had been bumped up into the Mercure that shared the same building, at the original Ibis Budget price. Good deal. Strangely, we were asked to fill out forms at check-in, with our names, addresses, and passport numbers! When I remarked that this was the first time on the trip that we hadn't just been handed room keys, without formalities, the clerk insisted that all French hotels always ask you to fill out the forms. Odd.

There was an elevator, but once we reached our floor, we had to wrestle our luggage through no fewer than six heavy fire doors to reach our rooms! By then, it was 4 p.m., and we were hot, tired, and exasperated, so we decided just to put off the visitors' center until the next day, before we left for Montpellier. Because we had kept Montpellier flexible to accommodate our friends, we didn't have a lot planned for our two days there aside from the Musée Fabre.

The rooms did have spectacular views, though, of both the countryside and the viaduct.

Dinner that night was at Le Diapason, in nearby Creissei\ls, which we had actually passed on our way to Millau—one of the very few restaurants we had to drive to on this trip.

Dinner that night was at Le Diapason, in nearby Creissei\ls, which we had actually passed on our way to Millau—one of the very few restaurants we had to drive to on this trip.

I checked out their website, so see if the menu was posted (it was and was quite short), and discovered that the owner had introduced the innovation, for the region, of combining dinner with music; tonight was samba night, with a guest band from South America. Okay, we can live with that; we like samba. It could have been disco or heavy metal. We chose the menu at 29.50 euros, which offered a couple of choices for each course.

First course, David: Duck foie gras with toasted pain d'épice and three compotes (fig, apricot, and something, I think). The plate was dedorated with a little pinwheel made of dried apricots and figs.

First course, me: Fricasée of lamb sweetbreads "entre terre et mer," that is, between land and sea, because the sauce had seafood in it. The sweetbreads themselves were a little hard (overcooked, I think), but the sauce was delicious, and was topped with fried spinach and frizzled leek shreds.

Main course, both: Declension of lamb—a rib chop, a little t-bone steak, a slice from the saddle, and a little piece of tender braised lamb. The chop was, frankly, tough, but it was very flavorful. The round dish is full of sautéed eggplant, and at the back is a pile of tasty stewed green beans. Each plate was garnished with four large, tasty, roasted cloves of garlic. Finally, at the lower left, a cake of sautéed "aligot," a mixture of mashed potato, garlic, and young tomme de Savoie cheese. Yummy!

Main course, both: Declension of lamb—a rib chop, a little t-bone steak, a slice from the saddle, and a little piece of tender braised lamb. The chop was, frankly, tough, but it was very flavorful. The round dish is full of sautéed eggplant, and at the back is a pile of tasty stewed green beans. Each plate was garnished with four large, tasty, roasted cloves of garlic. Finally, at the lower left, a cake of sautéed "aligot," a mixture of mashed potato, garlic, and young tomme de Savoie cheese. Yummy!

Dessert, both: Flaune, a sort of local cheesecake made with "brousse de brebis," fresh sheeps' milk cheese curds. Moist and granular, not very sweet. It's something I'd wanted to try, and it was pretty good, but I probably wouldn't order it again. The strange red, green, and blue object on top of it is a decorative sheet of crispy strands of colored sugar.

We could have done without the flies in the dining room, which was open to the patio where the musicians were playing, but the samba music was entirely agreeable, soft and gentle.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Then it was off to Roquefort, which you have to visit on a day-trip because it has no hotel; the village is actually very small. A few miles outside Albi, we encountered our first field of colza (oil-seed rape). We passed a couple of wineries, but no vines, mostly just grain and pasture/hay.

Then it was off to Roquefort, which you have to visit on a day-trip because it has no hotel; the village is actually very small. A few miles outside Albi, we encountered our first field of colza (oil-seed rape). We passed a couple of wineries, but no vines, mostly just grain and pasture/hay.

We arrived about 11:30 a.m. and signed up for the noon guided tour. The waiting room was well furnished with exhibits and reading material on the subject of cheese, and a television in the corner played a continuous loop of old Roquefort TV commercials.

We arrived about 11:30 a.m. and signed up for the noon guided tour. The waiting room was well furnished with exhibits and reading material on the subject of cheese, and a television in the corner played a continuous loop of old Roquefort TV commercials.

While we watched, lightning flashed, thunder rolled, the earth groaned, and the land began to shift and slide, and that in the foreground sank. At the left is the landscape right after the huge earthquake that created the Roquefort caves.

While we watched, lightning flashed, thunder rolled, the earth groaned, and the land began to shift and slide, and that in the foreground sank. At the left is the landscape right after the huge earthquake that created the Roquefort caves.

After the earthquake model, we saw a short film that showed all the steps in the process of producing roquefort, framed as brief, almost wordless visual profiles of individual employees of the company, listing their names, length of time in their jobs, and what they do in the production chain, from shepherds to distribution drivers.

After the earthquake model, we saw a short film that showed all the steps in the process of producing roquefort, framed as brief, almost wordless visual profiles of individual employees of the company, listing their names, length of time in their jobs, and what they do in the production chain, from shepherds to distribution drivers.

The aging cave we saw most of is called "Rue" (street), simply because, of Société's underground holdings, it's the one nearest the street. Here's its information panel, at the left: floor area, 590 m2; ripening surface (i.e., shelf space for cheeses), 700 m2; ripening capacity, 23,000 loaves (the whole wheels of cheese are called loaves). The cheeses ripened here are of Société's "medium" variety, the one commonly available on the market and the one they produce in by far the largest quantities. In other, smaller, caves, they produce a stronger-flavored and a milder-flavored variety, available only is more specialized shops.

The aging cave we saw most of is called "Rue" (street), simply because, of Société's underground holdings, it's the one nearest the street. Here's its information panel, at the left: floor area, 590 m2; ripening surface (i.e., shelf space for cheeses), 700 m2; ripening capacity, 23,000 loaves (the whole wheels of cheese are called loaves). The cheeses ripened here are of Société's "medium" variety, the one commonly available on the market and the one they produce in by far the largest quantities. In other, smaller, caves, they produce a stronger-flavored and a milder-flavored variety, available only is more specialized shops.

After that, we had the chance to taste all three varieties (and to purchase them and any of Société's other cheeses as well, of course). The French folks were whipping out their wallets left and right, but buying any would not really have been practical for us. If we'd been staying in an apartment or gîte, with a kitchen, I would have loved to acquire one of the three-packs at the left-hand side of the left-hand photo, containing 1/6 of a wheel of each of the varieties.

After that, we had the chance to taste all three varieties (and to purchase them and any of Société's other cheeses as well, of course). The French folks were whipping out their wallets left and right, but buying any would not really have been practical for us. If we'd been staying in an apartment or gîte, with a kitchen, I would have loved to acquire one of the three-packs at the left-hand side of the left-hand photo, containing 1/6 of a wheel of each of the varieties.

All over the place were posters from current and previous advertising campaigns, including this series of Roquefort carved (or CGI'd) into the shapes of foods it goes well with (and dice; does it go well with gambling games?).

All over the place were posters from current and previous advertising campaigns, including this series of Roquefort carved (or CGI'd) into the shapes of foods it goes well with (and dice; does it go well with gambling games?).

During the ensuing 14 to 25 days, the mold spores develop and produce the blue veining so prominent in Roquefort. The cheeses are not turned, basted, or otherwise fiddled with during that time, but after 14 days, the cellar master starts testing them. He selects one from each batch; uses a coring tool to pull out a sample; feels, smells, and examines the sample; they puts it back in its hole in the cheese.

During the ensuing 14 to 25 days, the mold spores develop and produce the blue veining so prominent in Roquefort. The cheeses are not turned, basted, or otherwise fiddled with during that time, but after 14 days, the cellar master starts testing them. He selects one from each batch; uses a coring tool to pull out a sample; feels, smells, and examines the sample; they puts it back in its hole in the cheese.

It was after 1 before we finished the tour, and restaurants are few in the tiny town, so for lunch we simply repaired to the company's affiliated restaurant, just above the parking lot. As you might expect, every item on the menu contained roquefort.

It was after 1 before we finished the tour, and restaurants are few in the tiny town, so for lunch we simply repaired to the company's affiliated restaurant, just above the parking lot. As you might expect, every item on the menu contained roquefort.

Dinner that night was at Le Diapason, in nearby Creissei\ls, which we had actually passed on our way to Millau—one of the very few restaurants we had to drive to on this trip.

Dinner that night was at Le Diapason, in nearby Creissei\ls, which we had actually passed on our way to Millau—one of the very few restaurants we had to drive to on this trip.

Main course, both: Declension of lamb—a rib chop, a little t-bone steak, a slice from the saddle, and a little piece of tender braised lamb. The chop was, frankly, tough, but it was very flavorful. The round dish is full of sautéed eggplant, and at the back is a pile of tasty stewed green beans. Each plate was garnished with four large, tasty, roasted cloves of garlic. Finally, at the lower left, a cake of sautéed "aligot," a mixture of mashed potato, garlic, and young tomme de Savoie cheese. Yummy!

Main course, both: Declension of lamb—a rib chop, a little t-bone steak, a slice from the saddle, and a little piece of tender braised lamb. The chop was, frankly, tough, but it was very flavorful. The round dish is full of sautéed eggplant, and at the back is a pile of tasty stewed green beans. Each plate was garnished with four large, tasty, roasted cloves of garlic. Finally, at the lower left, a cake of sautéed "aligot," a mixture of mashed potato, garlic, and young tomme de Savoie cheese. Yummy!