Thursday, 16 October: The brewery and Laoshan

Okay, Thursday, I remembered to take photos! I took so many I had to change our my camera battery partway along. Glad I brought along a spare.

As planned, we had breakfast in the revolving restaurant again, then walked up to the Huang Hai, cash in hand, to meet the bus for our day-long tour of the Tsingtao brewery and "Mount Laoshan," which should, I'm told, just be called "Laoshan," since "shan" means mountain.

Our guide was a cheerful young man who, as promised, spoke quite good English, although he occasionally had to refer to his cell phone for a word he couldn't remember. As we usually do in these cases, we sat immediately behind him, so during parts of the drive when he wasn't lecturing, I could ask things like what kind of cooking oil we saw being used so liberally. In Qingdao and its region, he replied without hesitation, it would be peanut oil. Elsewhere, it might be colza (i.e., canola) or (and he had to look up the word) corn. He was quite well traveled for one so young, so we also asked whether he'd been to the U.S. No, he said. He'd applied for a visa, but when they saw from the stamps on his passport that he had recently visited North Korea (less than 500 miles away, as the crow flies), he was refused a visa and told to try again once five years had elapsed since that visit.

The brewery was our first stop. Tsingtao is now a major international brand, with dozens of breweries in China, but this one is the first and original. It was founded by the Germans during the years of the concession, so much of the original equipment was imported from Germany. After World War II, it was briefly privately Chinese-owned, but in 1949 it was nationalized. It was privatized again in 1990, and since then parts of it have been bought and sold by other beer companies, including Asahi and Anheuser-Busch.

The brewery was our first stop. Tsingtao is now a major international brand, with dozens of breweries in China, but this one is the first and original. It was founded by the Germans during the years of the concession, so much of the original equipment was imported from Germany. After World War II, it was briefly privately Chinese-owned, but in 1949 it was nationalized. It was privatized again in 1990, and since then parts of it have been bought and sold by other beer companies, including Asahi and Anheuser-Busch.

As you can see in the left-hand photo, the water tanks on the roof are painted to resemble cans of beer (the Qingdao brewery is the only one that can still boast of using only Laoshan water). On the right is a photo of a fountain in the main courtyard, in the shape of an overflowing bottle of beer surrounded by overflowing goblets.

This was our first opportunity ever actually to use the transmitter-and-earbud system of guided tour. Tours were going on all around us, mostly in Chinese, but we couldn't hear them and had only our own guide's voice directly in our ears (our Tsingtao Brewery guide, that is, not the one for the bus trip).

This was our first opportunity ever actually to use the transmitter-and-earbud system of guided tour. Tours were going on all around us, mostly in Chinese, but we couldn't hear them and had only our own guide's voice directly in our ears (our Tsingtao Brewery guide, that is, not the one for the bus trip).

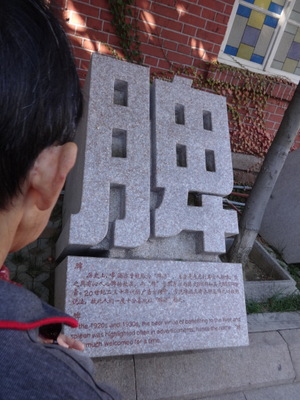

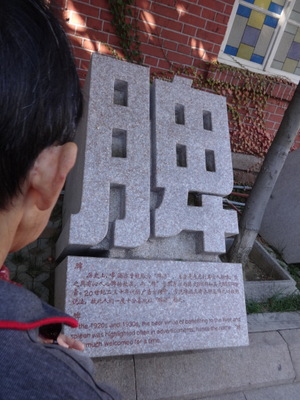

Just inside the main gates were half a dozen carved granite things (posts? signs? sculptures?), of which I show two here. On the left, "BIER." The inscription below it (in Chinese and English, but not German) says "Bier is the German substitute for beer. The word BIER has been widely adopted in Qingdao since November 14th, 1897, when Jiaoao (old name for Tsingtao) was occupied by the German."

On the right, a couple of Chinese characters. The inscription reads "In the 1920s and 1930s, the beer virtue of benefiting to the liver and spleen was highlighted often in advertisements, hence the name "[Chinese characters]" was much welcomed for a time."

Elsewhere in the courtyard was this arbor with a rather sparse hop vine growing on it and this suspended spigot, continuously spewing (something that looked like) beer into a barrel.

Elsewhere in the courtyard was this arbor with a rather sparse hop vine growing on it and this suspended spigot, continuously spewing (something that looked like) beer into a barrel.

When I was a kid, the North Carolina State Fair always had a similar display in one of the pavilions—a regular lead-pipe-style spigot, suspended by a wire but otherwise unconnected to anything and continuously spewing water into a barrel beneath. My father challenged me to deduce how it was done, and it took me a couple of years to figure out that a clear glass tube projected up from the barrel and into the mouth of the spigot, spewing water upward that then poured back down the outside of the tube, making it look like a solid column of water.

<>p>

In the center of the courtyard, facing the gate was this contemporary sculpture of the number 100, created to mark the brewery's 100th anniversary.

In the center of the courtyard, facing the gate was this contemporary sculpture of the number 100, created to mark the brewery's 100th anniversary.

Once inside the building, we were shown a large collection of old cast-iron equipment, including many pumps, now disused but still in working order, as well as this antique wooden malt shovel, a reminder of now-mechanized tasks that used to be done by hand.

I would have liked to spend more time looking at the exhibits, which were extensive and well labeled—more complete and informative than those of any other brewery we've ever toured—but unfortunately, we were on a schedule, and the guide moved us along pretty quickly.

Other antiques included several of these wonderful old brewing kettles, and the museum included (as has every brewery and beer museum we've ever toured) a large collection of beer bottles and cans from the world over. Only a fraction is shown here.

Other antiques included several of these wonderful old brewing kettles, and the museum included (as has every brewery and beer museum we've ever toured) a large collection of beer bottles and cans from the world over. Only a fraction is shown here.

We strode through room after room of exhibits about the brewery's history, the beer's advertising campaigns over the years, changes in its composition (it's no longer governed by Germany's 16th century purity laws, so rice has been added, in addition to the regulation barley, water, yeast, and hops), and changes in brewing chemistry and technology, plus models of the brewery itself at different stages of its history. I took pictures of as many panels as I could (maybe two per room, out of a couple of dozen), but we had to keep moving on. You could easily spend a day or two if you wanted to read it all. It's clearly set up for both Chinese-speaking and English-speaking visitors, but we saw no other westerners.

At one point, we did get to pause to taste malt roasted to different degrees.

A highlight of the tour was our passage through the bottling area, where thousands of bottles and cans were zooming around on conveyer belts, being cleaned, filled, sealed, labeled, packed for shipping, etc. Only a few actual people were working there, including one guy whose entire job was to add a sheet of cardboard to each cardboard box on its way to the machine that filled it with 24 bottles of beer. The piece he added was the plain rectangle that fitted into the bottom of the box to form a smooth surface on top of the flaps folded in to form the bottom of the box. He had just the right move to make that sheet of cardboard float right to the bottom of the box, without turning sideways and hanging up against the sides.

At the end of the tour was a tasting, first of "raw beer," then of regular filtered and pasturized beer. The "raw beer" is unfiltered, and we were told it lasts only a day. In season, they "bottle" it in plastic bags with handles and a straw, and a very touristy thing to do in Qingdao is to go out at night to wander the streets, drinking raw beer through a straw and eating the most popular local street snack, squid on a stick. (The squid's hood is about the size of my hand, fingers included, and it's impaled pointed-end-down, so the tentacles stick up in the air and draggle downward on all sides.)

I tasted both beers from David's glass and found the raw beer better (i.e., less distasteful) than the other, but I wouldn't drink either one for choice.

Then, to wait for our bus, we were ushered into a sort of Sino-Germanic Biergarten, where we could order more beer, and its attached gift shop which featured, among many, many other things, these beer-flavored teas and hop-flavored coffees. Also barley tea; beer-, barley, and hop-flavored soaps, candies, crackers, etc., etc. And Tsingtao-logo coasters and bottle openers of at least 20 designs each.

Then, to wait for our bus, we were ushered into a sort of Sino-Germanic Biergarten, where we could order more beer, and its attached gift shop which featured, among many, many other things, these beer-flavored teas and hop-flavored coffees. Also barley tea; beer-, barley, and hop-flavored soaps, candies, crackers, etc., etc. And Tsingtao-logo coasters and bottle openers of at least 20 designs each.

Back in the bus, we were then driven to our lunch restaurant, which I never really got the name of (unless that's it in the medallion above the huge red jade fish I showed a photo of somewhere above). It was billed, though, as We specializing in the cuisine of Qingdao and Shandong (its surrounding region). We were seated at several large round tables, each with abbig glass lazy-susan in the center, and they just started bringing food. No labels or explanations, so the vegetarians in the crowd just had to take their chances.

Here's one of the tables, before we sat down. We each got a plate, a bowl with porcelain spoon, a tall octagonal cup, and a pair of chopsticks. For those who wanted them, knives and forks were supplied on a dish on the lazy susan.

Here's one of the tables, before we sat down. We each got a plate, a bowl with porcelain spoon, a tall octagonal cup, and a pair of chopsticks. For those who wanted them, knives and forks were supplied on a dish on the lazy susan.

At the right is the my portion of the first food item, a floured and deep-fried half chicken wing. Well seasoned and delicious. We were brought a plate of them and spun it around the lazy-susan until everyone had gotten one (except the Russian sitting to my left, who seemed to eat seafood but not meat and chose to pass it up).

Next came this dish of what seemed to be beef cooked with onions and bell peppers in brown sauce. It came with curly salad greens, which we left strictly alone, as they were clearly raw, but the Russian decided to chance them.

Next came this dish of what seemed to be beef cooked with onions and bell peppers in brown sauce. It came with curly salad greens, which we left strictly alone, as they were clearly raw, but the Russian decided to chance them.

Next was pork and mushrooms in a brown sauce, very similar to a dish we'd already had a couple of times, but including a new element we hadn't seen before—a handful of small, yellow, semitransparent, teardrop-shaped fruits. I have no idea what they were; they had a strange, waxy texture and not much flavor. At the enter of each was a small lacuna but no visible seed. Any of you readers have a clue?

We got to use our bowls and spoons when they brought this soup, which I had already seen on the Huang Hai's lunch buffet. It's a thin tomato-based broth full of shreds of cooked eggs (egg-drop style). Tasty enough but not a standout.

We got to use our bowls and spoons when they brought this soup, which I had already seen on the Huang Hai's lunch buffet. It's a thin tomato-based broth full of shreds of cooked eggs (egg-drop style). Tasty enough but not a standout.

That was followed by lightly stirfried broccoli with garlic. At this point, the vegetarian was finally getting something to eat! They didn't wait for us to finish one dish before bringing the next, so we were all developing a variety of items on our plates.

This plate of scallops grilled on the half shell was up next. Again, the scallops were just opened and grilled, complete with muscle, roe, mantle, and viscera. Again the mantle was tasty but pretty tough. The vegetarian was willing to eat the scallops.

This plate of scallops grilled on the half shell was up next. Again, the scallops were just opened and grilled, complete with muscle, roe, mantle, and viscera. Again the mantle was tasty but pretty tough. The vegetarian was willing to eat the scallops.

At the right is a photo of the back of one of the scallop shells, in case any of you readers is able to identify the species from that.

At the left here are steamed dumplings filled with a meat and vegetables. They were excellent: juicy, flavorful, and well seasoned.

At the left here are steamed dumplings filled with a meat and vegetables. They were excellent: juicy, flavorful, and well seasoned.

At the right is the only dish about which anyone expressed squeamishness. It arrived as a large platter with a heap of shredded raw carrot at one end, a heap of shredded raw cucumber at the other, and in the middle a larger heap of pale lavender transparent noodles, but what noodles! They were huge, perhaps an inch wide, half an inch thick, and about 12 inches long! They were dressed with a sort of clear mustard vinaigrette, and they were slippery as all get out, really hard to handle with chopsticks. The platter happened to be set down in front of me, so I immediately dug in and managed to transfer an entire noodle to my plate before rotating it toward the next person. Meanwhile, the waitress, who had turned aside to pick up implements, hurried to catch up with the platter and toss the whole thing together, mixing the raw veggies, which we weren't supposed to eat, in with the noodles. Even before that, though others at the table were peering at the dish suspiciously, saying, "Is that jellyfish? I don't think I want jellyfish. I'll bet that's jellyfish." Meanwhile, I'm responding, "No, it's not jellyfish. I've had jellyfish, and it doesn't look anything like this. Honest, I've just tasted one; they're just big slippery noodles." And these were supposed to be marine biologists! Couldn't they see that it wasn't jellyfish?! I looked the dish up later on the internet, and yes, it was rice noodles, a specialty of the region. A lot got left on the platter, though.

Much more popular were these pot stickers, also stuffed with meat, but much larger than the usual little half-moon dumplings (like the steamed ones above. Each one was about eight inches long, and they were really good. better than the already-good steamed ones. I couldn't believe that no one else wanted the one the vegetarian left on the platter—I bagged it myself.

Much more popular were these pot stickers, also stuffed with meat, but much larger than the usual little half-moon dumplings (like the steamed ones above. Each one was about eight inches long, and they were really good. better than the already-good steamed ones. I couldn't believe that no one else wanted the one the vegetarian left on the platter—I bagged it myself.

Then the final dish, shown here at the right, of eggplant with garlic and green chilis. Excellent. Clearly in the same family as the garlic eggplant at Bamboo House in Tallahassee, but drier and less sweet.

Finally, here's the dish of fried rice that appeared on the table toward the end and, on the right a view of the table when we finished eating.

Finally, here's the dish of fried rice that appeared on the table toward the end and, on the right a view of the table when we finished eating.

As you can see, the only dishes with much left in them were the rice, which really arrived a little late to get eaten, and the rice noodles, just below 3 o'clock, which half the table remained convinced were jellyfish.

After taking the photo, I polished off the last dumpling, the last potsticker, and that last dab of eggplant

Our next stop was Laoshan, about an hour north of the city. The mountain sits in a vast park, aproached through a huge modern visitors' center that looks like an airport lobby. Our tour bus wasn't allowed into the park. It had to drop us off at the visitors' center, where our guide went off in search of our prearranged admission tickets. Finally, equipped with our individual tickets, we were ushered through the visitors' center and out the other side, where park-specific shuttle buses were waiting to take us to the park proper, about 15 minutes away via a twisting road that followed the rocky seashore, as shown at the left.

Our next stop was Laoshan, about an hour north of the city. The mountain sits in a vast park, aproached through a huge modern visitors' center that looks like an airport lobby. Our tour bus wasn't allowed into the park. It had to drop us off at the visitors' center, where our guide went off in search of our prearranged admission tickets. Finally, equipped with our individual tickets, we were ushered through the visitors' center and out the other side, where park-specific shuttle buses were waiting to take us to the park proper, about 15 minutes away via a twisting road that followed the rocky seashore, as shown at the left.

Once we arrived at the little village of cafes and shops that forms the center of the park, our guide pointed out the trailhead of the route we were to follow. He explained that we should go only as far as the bridge and waterfall before turning back; if we went on to the temple beyond, we wouldn't be back in time to get shuttled back to our tour bus in time to stay on schedule (we learned later that much of the urgency arose because, if he didn't get the tour bus back to base by 5 p.m., he and the tour company he works for would have to pay extra for the bus and its driver). He showed us the fire station, whose bright red roof made it unmistakable, and told us please, without fail, to be back there by the appointed hour of 3:30 p.m.

At the right above is a map of the available roads and walking paths in the park. The one we took is the right-most of the thin lines on the map. The first little icon on it is the bridge and waterfall, the second is a faint green icon marking restrooms, and the third is the temple.

We had been told by friends who had visited the park that only about the first kilometer of the path had been paved, but as it turned out, that was plenty to get us to the bridge and waterfall. As we approached the trailhead, however, we found that it consisted of a set of cement stairs that climbed about four stories just to reach the turnstyle that marked the beginning of the trail. We set off, but I'm not a terrific climber, so I and an older Russian lady colleague were moving slowly. Meanwhile most of the rest of the group, consisting of strapping young field scientists set off at a great pace and disappeared through the turnstyle long before we got there. I took the photo at the left after I was most of the way to the top. At the turnstyle, we presented our tickets and passed through, only to find that the stairs kept going up! And they never stopped going up! Well, here and there, the trail was flat for 20 feet or so, and occasionally you even went down five or ten steps, but then you had to reclaim that altitude on the other side and climb back up again.

We had been told by friends who had visited the park that only about the first kilometer of the path had been paved, but as it turned out, that was plenty to get us to the bridge and waterfall. As we approached the trailhead, however, we found that it consisted of a set of cement stairs that climbed about four stories just to reach the turnstyle that marked the beginning of the trail. We set off, but I'm not a terrific climber, so I and an older Russian lady colleague were moving slowly. Meanwhile most of the rest of the group, consisting of strapping young field scientists set off at a great pace and disappeared through the turnstyle long before we got there. I took the photo at the left after I was most of the way to the top. At the turnstyle, we presented our tickets and passed through, only to find that the stairs kept going up! And they never stopped going up! Well, here and there, the trail was flat for 20 feet or so, and occasionally you even went down five or ten steps, but then you had to reclaim that altitude on the other side and climb back up again.

The Russian lady and I carried on valiantly, though slowly, and David stayed with us for a good ways, but we finally told him to go on ahead, which he did. The photo at the left shows the view I got when I stopped to rest and looked back down the way we had come.

All along the way, wherever a flat spot was available, and many places where it wasn't, were vendors of food (left) and souvenirs (right). All the souvenir stands seemed to have the same stuff—many, many figurines made of china, plaster, plastic, or jade dragons, dogs, Bhuddas, cabbages, crabs, fish, frogs, turtles, mice, warriors, horses, doll furniture); six-inch-long plastic peanuts that, when opened, played bird songs; key chains; bracelets; miniature shopping carts; jewelry; bamboo snakes and crocodiles. The food stands, on the other hand, seemed to specialize in dried seafood (although a few offered squash and huge green-and-white daikon radishes) but their assortments were widely varied. I don't know whether the seafood was to be eaten on the spot out of hand or whether it was to be taken home and cooked. Most stands also offered colds soft drinks.

All along the way, wherever a flat spot was available, and many places where it wasn't, were vendors of food (left) and souvenirs (right). All the souvenir stands seemed to have the same stuff—many, many figurines made of china, plaster, plastic, or jade dragons, dogs, Bhuddas, cabbages, crabs, fish, frogs, turtles, mice, warriors, horses, doll furniture); six-inch-long plastic peanuts that, when opened, played bird songs; key chains; bracelets; miniature shopping carts; jewelry; bamboo snakes and crocodiles. The food stands, on the other hand, seemed to specialize in dried seafood (although a few offered squash and huge green-and-white daikon radishes) but their assortments were widely varied. I don't know whether the seafood was to be eaten on the spot out of hand or whether it was to be taken home and cooked. Most stands also offered colds soft drinks.

Presumably all those vendors had to carry their daily restock (and ice for the drink coolers!) up the mountain every morning. In fact, another item offered for sale here and there along the way was rides in sedan chairs of varying degrees of opulence. I saw lots of young men waiting around to carry them but spotted no customers and passed no such conveyances either coming or going.

Along the way, we passed this lovely little artificial lake, Dragon Pond, formed by a tall dam across the tiny Bashui River, which we were following up the hill.

Along the way, we passed this lovely little artificial lake, Dragon Pond, formed by a tall dam across the tiny Bashui River, which we were following up the hill.

A short distance beyond that was the scenic bridge that was our destination. We caught up with David, who was waiting for us, reading his Kindle on a bench within sight of the bridge. He'd stopped there when he saw that he'd have to descend about 30 steps, then climb up again, to get to the bridge. My Russian companion decided to join him on the bench, but I went on, now that I could actually see how much farther I had to go—only a couple of hundred yards.

The photo at the right shows some of the hundreds of romantic little brass padlocks, each beribboned in red, that lovers have attached to the metal railings of the bridge. A couple of specialized vendors near the bridge sell nothing but those little padlocks, ribbon already attached, and will even engrave them while you wait.

Visible from the bridge is the famous Yulong waterfall, 30 m high (the highest in eastern China, I think they said), designated one of the "12 landscapes of Laoshan."

Visible from the bridge is the famous Yulong waterfall, 30 m high (the highest in eastern China, I think they said), designated one of the "12 landscapes of Laoshan."

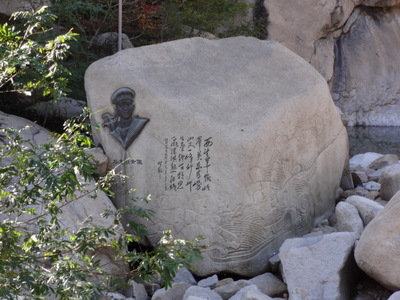

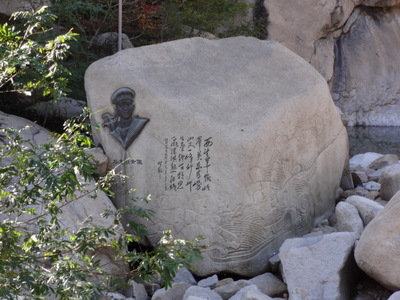

Around it are many engravings, including this one (just to the left of the foot of the waterfall and somewhat closer to the bridge) with a bronze image of a sailor and an inscription no one offered a translation of.

I admired the view for a while before heading back to rejoin David and our Russian colleague. Reclimbing that 30-step descent near the bridge was by far the longest climb I had to make on the way back. We still had plenty of time to get back down all those stairs by the appointed rendezvous time, so we started back—I wanted to take the descent as slowly as the climb, as my knees suffer far more from going down stairs than up, and the others were in agreement. At no point did we encounter any other member of our party. I expected to find at least some of them at the bridge, but they were nowhere in sight.

When we got back to the bottom, we were hailed by our tour guide, who was waiting for us on a deserted café terrace. When he asked where the others were, and I said we hadn't seen them since they outdistanced us in the first 10 minutes and that I handn't found them at the bridge, he was ready to panic! Oh, no! They've gone on to the temple! They'll never be back in time! But they were— the last of them showed up with minutes to spare, assuring us cheerfully that the stroll to the temple and back had been a piece of cake, that the trail was much less steep beyond the bridge, etc.

Our guide's worries were not over, though. Back at the pick-up point, where we were supposed to catch the shuttle bus back to the visitors' center, bus after bus went by because none of them had enough vacant seats to accommodate our party. We passed the time admiring this enormous replica of a whelk, surmounted by an inscription we couldn't read. It must be famous, as it was very popular with all the Chinese tourists, all of whom took turns photographing each other in front of it. When they were photographing the whelk, they were photographing us! Car-load after carload of Chinese folks rolled up, lowered their windows, took a shot or two of the whelk, turned their cameras to take a shot of us, then closed the windows and drove on. The guide got more and more worried, as he saw the slack in his schedule evaporate.

Our guide's worries were not over, though. Back at the pick-up point, where we were supposed to catch the shuttle bus back to the visitors' center, bus after bus went by because none of them had enough vacant seats to accommodate our party. We passed the time admiring this enormous replica of a whelk, surmounted by an inscription we couldn't read. It must be famous, as it was very popular with all the Chinese tourists, all of whom took turns photographing each other in front of it. When they were photographing the whelk, they were photographing us! Car-load after carload of Chinese folks rolled up, lowered their windows, took a shot or two of the whelk, turned their cameras to take a shot of us, then closed the windows and drove on. The guide got more and more worried, as he saw the slack in his schedule evaporate.

Eventually, the guide took half the party on one shuttle bus and left careful instructions with the guys directing bus traffic to make sure the rest of us stayed together and got on the next bus. In the end, we didn't even pass back through the visitors' center—we met up with our tour bus by the side of some country road, piled aboard, and headed for town at speed. In the end, we made it by the deadline. David though he overheard something about the electonic turnstiles' being down at the visitors' center anyway.

I had been impressed at how anxious they seemed to ensure that every single person was back down off the mountain by closing time—they even fingerprinted us electronically as we passed through to board the shuttle bus—but I guess that system was all for naught, since they never checked us back out again. In the end, we did make it back to town by the deadline.

After heading back to our hotel to wash up, we walked back up to the Huang Hai to take another shot at eating in the restaurant with the wall of food. Here are a couple more shots of their "menu wall." We examined it with a little more knowledgeable eye this time, but in the end we ordered again from the "set dishes" section.

After heading back to our hotel to wash up, we walked back up to the Huang Hai to take another shot at eating in the restaurant with the wall of food. Here are a couple more shots of their "menu wall." We examined it with a little more knowledgeable eye this time, but in the end we ordered again from the "set dishes" section.

Here are our choices, both as they appeared in the raw state. On the left pork stirfried with mushrooms and celery again.

Here are our choices, both as they appeared in the raw state. On the left pork stirfried with mushrooms and celery again.

On the right, "colorful chrystal shrimp," which included a bunch more of those odd little tear-drop-shaped yellow fruits. These were a little more cooked than the ones at lunch, and they had a texture like a cold cooked new potato.

Both were very good. We'd spotted the water cooler by this time, so we ordered cold water to drink.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

The brewery was our first stop. Tsingtao is now a major international brand, with dozens of breweries in China, but this one is the first and original. It was founded by the Germans during the years of the concession, so much of the original equipment was imported from Germany. After World War II, it was briefly privately Chinese-owned, but in 1949 it was nationalized. It was privatized again in 1990, and since then parts of it have been bought and sold by other beer companies, including Asahi and Anheuser-Busch.

The brewery was our first stop. Tsingtao is now a major international brand, with dozens of breweries in China, but this one is the first and original. It was founded by the Germans during the years of the concession, so much of the original equipment was imported from Germany. After World War II, it was briefly privately Chinese-owned, but in 1949 it was nationalized. It was privatized again in 1990, and since then parts of it have been bought and sold by other beer companies, including Asahi and Anheuser-Busch.

This was our first opportunity ever actually to use the transmitter-and-earbud system of guided tour. Tours were going on all around us, mostly in Chinese, but we couldn't hear them and had only our own guide's voice directly in our ears (our Tsingtao Brewery guide, that is, not the one for the bus trip).

This was our first opportunity ever actually to use the transmitter-and-earbud system of guided tour. Tours were going on all around us, mostly in Chinese, but we couldn't hear them and had only our own guide's voice directly in our ears (our Tsingtao Brewery guide, that is, not the one for the bus trip).

Elsewhere in the courtyard was this arbor with a rather sparse hop vine growing on it and this suspended spigot, continuously spewing (something that looked like) beer into a barrel.

Elsewhere in the courtyard was this arbor with a rather sparse hop vine growing on it and this suspended spigot, continuously spewing (something that looked like) beer into a barrel.

In the center of the courtyard, facing the gate was this contemporary sculpture of the number 100, created to mark the brewery's 100th anniversary.

In the center of the courtyard, facing the gate was this contemporary sculpture of the number 100, created to mark the brewery's 100th anniversary.

Other antiques included several of these wonderful old brewing kettles, and the museum included (as has every brewery and beer museum we've ever toured) a large collection of beer bottles and cans from the world over. Only a fraction is shown here.

Other antiques included several of these wonderful old brewing kettles, and the museum included (as has every brewery and beer museum we've ever toured) a large collection of beer bottles and cans from the world over. Only a fraction is shown here.

Then, to wait for our bus, we were ushered into a sort of Sino-Germanic Biergarten, where we could order more beer, and its attached gift shop which featured, among many, many other things, these beer-flavored teas and hop-flavored coffees. Also barley tea; beer-, barley, and hop-flavored soaps, candies, crackers, etc., etc. And Tsingtao-logo coasters and bottle openers of at least 20 designs each.

Then, to wait for our bus, we were ushered into a sort of Sino-Germanic Biergarten, where we could order more beer, and its attached gift shop which featured, among many, many other things, these beer-flavored teas and hop-flavored coffees. Also barley tea; beer-, barley, and hop-flavored soaps, candies, crackers, etc., etc. And Tsingtao-logo coasters and bottle openers of at least 20 designs each.

Here's one of the tables, before we sat down. We each got a plate, a bowl with porcelain spoon, a tall octagonal cup, and a pair of chopsticks. For those who wanted them, knives and forks were supplied on a dish on the lazy susan.

Here's one of the tables, before we sat down. We each got a plate, a bowl with porcelain spoon, a tall octagonal cup, and a pair of chopsticks. For those who wanted them, knives and forks were supplied on a dish on the lazy susan.

Next came this dish of what seemed to be beef cooked with onions and bell peppers in brown sauce. It came with curly salad greens, which we left strictly alone, as they were clearly raw, but the Russian decided to chance them.

Next came this dish of what seemed to be beef cooked with onions and bell peppers in brown sauce. It came with curly salad greens, which we left strictly alone, as they were clearly raw, but the Russian decided to chance them.

We got to use our bowls and spoons when they brought this soup, which I had already seen on the Huang Hai's lunch buffet. It's a thin tomato-based broth full of shreds of cooked eggs (egg-drop style). Tasty enough but not a standout.

We got to use our bowls and spoons when they brought this soup, which I had already seen on the Huang Hai's lunch buffet. It's a thin tomato-based broth full of shreds of cooked eggs (egg-drop style). Tasty enough but not a standout.

This plate of scallops grilled on the half shell was up next. Again, the scallops were just opened and grilled, complete with muscle, roe, mantle, and viscera. Again the mantle was tasty but pretty tough. The vegetarian was willing to eat the scallops.

This plate of scallops grilled on the half shell was up next. Again, the scallops were just opened and grilled, complete with muscle, roe, mantle, and viscera. Again the mantle was tasty but pretty tough. The vegetarian was willing to eat the scallops.

At the left here are steamed dumplings filled with a meat and vegetables. They were excellent: juicy, flavorful, and well seasoned.

At the left here are steamed dumplings filled with a meat and vegetables. They were excellent: juicy, flavorful, and well seasoned.

Much more popular were these pot stickers, also stuffed with meat, but much larger than the usual little half-moon dumplings (like the steamed ones above. Each one was about eight inches long, and they were really good. better than the already-good steamed ones. I couldn't believe that no one else wanted the one the vegetarian left on the platter—I bagged it myself.

Much more popular were these pot stickers, also stuffed with meat, but much larger than the usual little half-moon dumplings (like the steamed ones above. Each one was about eight inches long, and they were really good. better than the already-good steamed ones. I couldn't believe that no one else wanted the one the vegetarian left on the platter—I bagged it myself.

Finally, here's the dish of fried rice that appeared on the table toward the end and, on the right a view of the table when we finished eating.

Finally, here's the dish of fried rice that appeared on the table toward the end and, on the right a view of the table when we finished eating.

Our next stop was Laoshan, about an hour north of the city. The mountain sits in a vast park, aproached through a huge modern visitors' center that looks like an airport lobby. Our tour bus wasn't allowed into the park. It had to drop us off at the visitors' center, where our guide went off in search of our prearranged admission tickets. Finally, equipped with our individual tickets, we were ushered through the visitors' center and out the other side, where park-specific shuttle buses were waiting to take us to the park proper, about 15 minutes away via a twisting road that followed the rocky seashore, as shown at the left.

Our next stop was Laoshan, about an hour north of the city. The mountain sits in a vast park, aproached through a huge modern visitors' center that looks like an airport lobby. Our tour bus wasn't allowed into the park. It had to drop us off at the visitors' center, where our guide went off in search of our prearranged admission tickets. Finally, equipped with our individual tickets, we were ushered through the visitors' center and out the other side, where park-specific shuttle buses were waiting to take us to the park proper, about 15 minutes away via a twisting road that followed the rocky seashore, as shown at the left.

We had been told by friends who had visited the park that only about the first kilometer of the path had been paved, but as it turned out, that was plenty to get us to the bridge and waterfall. As we approached the trailhead, however, we found that it consisted of a set of cement stairs that climbed about four stories just to reach the turnstyle that marked the beginning of the trail. We set off, but I'm not a terrific climber, so I and an older Russian lady colleague were moving slowly. Meanwhile most of the rest of the group, consisting of strapping young field scientists set off at a great pace and disappeared through the turnstyle long before we got there. I took the photo at the left after I was most of the way to the top. At the turnstyle, we presented our tickets and passed through, only to find that the stairs kept going up! And they never stopped going up! Well, here and there, the trail was flat for 20 feet or so, and occasionally you even went down five or ten steps, but then you had to reclaim that altitude on the other side and climb back up again.

We had been told by friends who had visited the park that only about the first kilometer of the path had been paved, but as it turned out, that was plenty to get us to the bridge and waterfall. As we approached the trailhead, however, we found that it consisted of a set of cement stairs that climbed about four stories just to reach the turnstyle that marked the beginning of the trail. We set off, but I'm not a terrific climber, so I and an older Russian lady colleague were moving slowly. Meanwhile most of the rest of the group, consisting of strapping young field scientists set off at a great pace and disappeared through the turnstyle long before we got there. I took the photo at the left after I was most of the way to the top. At the turnstyle, we presented our tickets and passed through, only to find that the stairs kept going up! And they never stopped going up! Well, here and there, the trail was flat for 20 feet or so, and occasionally you even went down five or ten steps, but then you had to reclaim that altitude on the other side and climb back up again.

All along the way, wherever a flat spot was available, and many places where it wasn't, were vendors of food (left) and souvenirs (right). All the souvenir stands seemed to have the same stuff—many, many figurines made of china, plaster, plastic, or jade dragons, dogs, Bhuddas, cabbages, crabs, fish, frogs, turtles, mice, warriors, horses, doll furniture); six-inch-long plastic peanuts that, when opened, played bird songs; key chains; bracelets; miniature shopping carts; jewelry; bamboo snakes and crocodiles. The food stands, on the other hand, seemed to specialize in dried seafood (although a few offered squash and huge green-and-white daikon radishes) but their assortments were widely varied. I don't know whether the seafood was to be eaten on the spot out of hand or whether it was to be taken home and cooked. Most stands also offered colds soft drinks.

All along the way, wherever a flat spot was available, and many places where it wasn't, were vendors of food (left) and souvenirs (right). All the souvenir stands seemed to have the same stuff—many, many figurines made of china, plaster, plastic, or jade dragons, dogs, Bhuddas, cabbages, crabs, fish, frogs, turtles, mice, warriors, horses, doll furniture); six-inch-long plastic peanuts that, when opened, played bird songs; key chains; bracelets; miniature shopping carts; jewelry; bamboo snakes and crocodiles. The food stands, on the other hand, seemed to specialize in dried seafood (although a few offered squash and huge green-and-white daikon radishes) but their assortments were widely varied. I don't know whether the seafood was to be eaten on the spot out of hand or whether it was to be taken home and cooked. Most stands also offered colds soft drinks.

Along the way, we passed this lovely little artificial lake, Dragon Pond, formed by a tall dam across the tiny Bashui River, which we were following up the hill.

Along the way, we passed this lovely little artificial lake, Dragon Pond, formed by a tall dam across the tiny Bashui River, which we were following up the hill.

Visible from the bridge is the famous Yulong waterfall, 30 m high (the highest in eastern China, I think they said), designated one of the "12 landscapes of Laoshan."

Visible from the bridge is the famous Yulong waterfall, 30 m high (the highest in eastern China, I think they said), designated one of the "12 landscapes of Laoshan." Our guide's worries were not over, though. Back at the pick-up point, where we were supposed to catch the shuttle bus back to the visitors' center, bus after bus went by because none of them had enough vacant seats to accommodate our party. We passed the time admiring this enormous replica of a whelk, surmounted by an inscription we couldn't read. It must be famous, as it was very popular with all the Chinese tourists, all of whom took turns photographing each other in front of it. When they were photographing the whelk, they were photographing us! Car-load after carload of Chinese folks rolled up, lowered their windows, took a shot or two of the whelk, turned their cameras to take a shot of us, then closed the windows and drove on. The guide got more and more worried, as he saw the slack in his schedule evaporate.

Our guide's worries were not over, though. Back at the pick-up point, where we were supposed to catch the shuttle bus back to the visitors' center, bus after bus went by because none of them had enough vacant seats to accommodate our party. We passed the time admiring this enormous replica of a whelk, surmounted by an inscription we couldn't read. It must be famous, as it was very popular with all the Chinese tourists, all of whom took turns photographing each other in front of it. When they were photographing the whelk, they were photographing us! Car-load after carload of Chinese folks rolled up, lowered their windows, took a shot or two of the whelk, turned their cameras to take a shot of us, then closed the windows and drove on. The guide got more and more worried, as he saw the slack in his schedule evaporate.

After heading back to our hotel to wash up, we walked back up to the Huang Hai to take another shot at eating in the restaurant with the wall of food. Here are a couple more shots of their "menu wall." We examined it with a little more knowledgeable eye this time, but in the end we ordered again from the "set dishes" section.

After heading back to our hotel to wash up, we walked back up to the Huang Hai to take another shot at eating in the restaurant with the wall of food. Here are a couple more shots of their "menu wall." We examined it with a little more knowledgeable eye this time, but in the end we ordered again from the "set dishes" section.

Here are our choices, both as they appeared in the raw state. On the left pork stirfried with mushrooms and celery again.

Here are our choices, both as they appeared in the raw state. On the left pork stirfried with mushrooms and celery again.