Saturday, 22 August 2015: Lisbon tours

Written 2 September 2015

The Tivoli's 7 a.m. breakfast buffet in the Brassierie Flo was gorgeous (and, even better, was included, together with the room, in our cruise price). At the left here is the cheese service—cubes of Brie in the foreground, and slices of various others behind. Dishes of fromage blanc, "cottage cheese" (not much like American cottage cheese), and honey to the side. At the back left, a platter of smoked salmon and a dish of lemon wedges (the capers and horseradish are hidden in this view).

The Tivoli's 7 a.m. breakfast buffet in the Brassierie Flo was gorgeous (and, even better, was included, together with the room, in our cruise price). At the left here is the cheese service—cubes of Brie in the foreground, and slices of various others behind. Dishes of fromage blanc, "cottage cheese" (not much like American cottage cheese), and honey to the side. At the back left, a platter of smoked salmon and a dish of lemon wedges (the capers and horseradish are hidden in this view).

In the right-hand photo, papaya (back left), peaches (front left), and white-fleshed melon. This kind of melon was absolutely ubiquitous. We saw them ripe in the fields and in the markets, and they were served at every breakfast and most lunches. They whole melons were whitish or yellow, oval, and at least a foot long, often more. When we asked what kind they were, we were told "mel&atilda;o" ("melon," as opposed to smaller, Charentais-type melons, which were called "meloa" and which we never tasted). Our cruise director, who was French, said they were "spanish melons." Kathy and I poked around on line and hypothesize that they are "canary melons." Really good, anyway, and they gave me no digestive trouble at all.

Here, we have raw ham, cooked ham, poultry ham, paio (a Portuguese smoked sausage for slicing), and mortadella (the label was untranslated on this occasion, but on a restaurant menu in Aveiro, I saw mortadella translated as "spam").

Here, we have raw ham, cooked ham, poultry ham, paio (a Portuguese smoked sausage for slicing), and mortadella (the label was untranslated on this occasion, but on a restaurant menu in Aveiro, I saw mortadella translated as "spam").

At the right is part of the bread assortment: miniature chocolate croissants, regular croissants, apple turnovers, and raisin buns; many kinds of bread roll; fruit bread, tiny muffins. to the right of this display was another whole assortment of sliced and sliceable breads, plus toasters. Honey, strawberry jam, orange marmelade, and peach jam in tiny jars on the tables.

On another counter was an assortment of yogurts and cereals, dried fruit, stewed prunes, fruit salad, and whole fruit. Then you came to the chafing dishes filled with pancakes (with maple syrup), scrambled eggs (not very good), giant omelet (even worse), excellent bacon, mushrooms, baked beans, little chicken sausages, and roasted tomatoes.

Here's my first plate of breakfast: bacon, a small chicken sausage, a chocolate croissant, a raisin bun, an apple turnover, some smoked salmon, a little scrambled egg, and a slice of mortadella. I went back later for some smoked salmon. There was no cream cheese, so I spread fromage blanc on a slice of country bread, salted and peppered it, and put the salmon on top. Wow—a revelation! My new favorite way to eat smoked salmon.

Here's my first plate of breakfast: bacon, a small chicken sausage, a chocolate croissant, a raisin bun, an apple turnover, some smoked salmon, a little scrambled egg, and a slice of mortadella. I went back later for some smoked salmon. There was no cream cheese, so I spread fromage blanc on a slice of country bread, salted and peppered it, and put the salmon on top. Wow—a revelation! My new favorite way to eat smoked salmon.

I ordered decaf coffee, which filled about half the cup, so I had the waiter fill the rest with hot milk, from the pitcher in his other hand. The mixture was still too fierce to drink, so I pulled over another cup, had him fill that one with just hot milk, and poured the two back and forth to mix. With some sugar, that was a good café au lait.

Outside the hotel, in the median of the large avenue, a "brocante" market was being set up. I guess you'd call it antiques, but there was nothing as large as furniture. Just tables and tables of curios, knick knacks, etc., so we browsed that while waiting for the buses to load. I only saw one tempting item, a little brass balance scale, but I resisted.

Then we piled aboard the buses for our morning tour. Here, at the left, Tour Director Miguel explains that he'll be moving from bus to bus during the morning but is starting out with us in Bus C.

Then we piled aboard the buses for our morning tour. Here, at the left, Tour Director Miguel explains that he'll be moving from bus to bus during the morning but is starting out with us in Bus C.

At the right is our "tour escort" Maria, who would be with us throughout the tour, introducing us to local guides and making sure everything went smoothly. Each of us was issued a "Quietvox" device, a little receiver we wore around our necks, together with a sterile earpiece in a little plastic bag, which you plug into the Quietvox and stuck in your left ear (the little clips that hold them in place are asymmetrical and thus ear-specific). Our guide could then speak in a conversational, or even quiet, tone, and her words were delivered right into our ears, without the need to shout, interfere with other tours nearby, or otherwise make ourselves more obnoxious than necessary. But, yes, our tour escort (or local guide, or whoever had the Quietvox transmitter at the time) carried aloft a red Viking "lollipop" with our bus number on it. At the end of each day (while we were in Lisbon), the Quietvoxes were collected for recharging.

After a short drive inland to circle the statue of Pombal while we listened to information about him, the bus headed for Belém, the oldest section of Lisbon, down on the waterfront. Our first stop was at this triangular memorial to those killed in the "overseas wars," the collective Portuguese name for the wars they fought in the 1960s, trying to retain all their former colonies. All the colonies became independent in 1974–75 (after the "carnation revolution") except Macao, which became independent in 1994). The little hut in front of it is one of a pair of sentry boxes (you can just see the edge of the second one at the left-hand edge of the photo). Two soldiers are always on guard there. The ones we saw were in camouflage fatigues, standing at parade rest. Every so often, they move—in our later photos they were standing under the monument itself rather than at the sentry boxes. The long white marble wall that surrounds the memorial on three sides is engraved with the names of all of those who died in the overseas wars (thousands and thousands).

After a short drive inland to circle the statue of Pombal while we listened to information about him, the bus headed for Belém, the oldest section of Lisbon, down on the waterfront. Our first stop was at this triangular memorial to those killed in the "overseas wars," the collective Portuguese name for the wars they fought in the 1960s, trying to retain all their former colonies. All the colonies became independent in 1974–75 (after the "carnation revolution") except Macao, which became independent in 1994). The little hut in front of it is one of a pair of sentry boxes (you can just see the edge of the second one at the left-hand edge of the photo). Two soldiers are always on guard there. The ones we saw were in camouflage fatigues, standing at parade rest. Every so often, they move—in our later photos they were standing under the monument itself rather than at the sentry boxes. The long white marble wall that surrounds the memorial on three sides is engraved with the names of all of those who died in the overseas wars (thousands and thousands).

Beyond the monument, across the harbor, we could see the cranes of the modern commercial port, here shown emptying a large freighter. Between the memorial and our next stop, just a few blocks away along the waterfront, was the army museum, which we had no time to visit.

At our second stop (near a replica of the airplane used by two Portuguese to make the first aerial crossing of the south Atlantic—Portugal to Brazil— in 1922), we visited the emblematic Tower of Belém, also called the Tower of St.Vincent.

At our second stop (near a replica of the airplane used by two Portuguese to make the first aerial crossing of the south Atlantic—Portugal to Brazil— in 1922), we visited the emblematic Tower of Belém, also called the Tower of St.Vincent.

It was was built in the early 1500s, originally as one element of a tripartite defense system that included another tower and a gun battery (I think), and was located out in the middle of the river. Since then, the river has shifted in its course and the tower is now close to the bank.

It opened in 1650 and later, after its defensive role ended, was used as a lighthouse and a prison. It represents the "Manueline" style of architectural decoration, as do most structures built in the same period, during the reign of King Manual.

By the side of the monument's parking lot was this cute little itinerant frozen-yogurt trailer, disguised as a Volkswagon minibus.

Next, again only a short distance away, the momument erected in the 1960s to Portugal's ocean-going explorers, who opened up most of the world to navigation. In distant view (left-hand photo) it is shaped like a stylized "caravelle," the kind of ship the explorers used, which was based on the Portuguese fishing vessel of the day.

Next, again only a short distance away, the momument erected in the 1960s to Portugal's ocean-going explorers, who opened up most of the world to navigation. In distant view (left-hand photo) it is shaped like a stylized "caravelle," the kind of ship the explorers used, which was based on the Portuguese fishing vessel of the day.

On each side of the monument, a line of 16 famous Portuguese explorers marches up the deck of the caravelle toward the prow, where Henry the Navigator (the Portuguese king credited with launching the age of exploration) stands holding a model of a caravelle. The other side is different, so 33 explorers are represented in all.

Each monumental figure portrays an actual historical personage (Portuguese school children can probably tell who's who from the flags they carry or their costume). Vasco da Gama (around the horn to India) and Magellan (first global circumnavitation) are in there somewhere. The monument was finished in time for the 500th anniversary of Henry's death.

Set into the paving of the plaza in front of the monument is this huge map of the world with all of Portugal's colonies, territories, and possessions marked on it, together with their dates of discovery or annexation.

Set into the paving of the plaza in front of the monument is this huge map of the world with all of Portugal's colonies, territories, and possessions marked on it, together with their dates of discovery or annexation.

Decorative compass roses, depictions of ships, blowing wind gods, etc., are scattered through the map. Around the sides are stylized mozaics representing plants and animals from the overseas locations.

Also nearby was this structure made of heavy wire mesh and spelling out "LOVE." As is the vogue in so many places these days, lovers had padlocked engraved hearts and ribbons to it. The photo at the right shows a closer view.

Also nearby was this structure made of heavy wire mesh and spelling out "LOVE." As is the vogue in so many places these days, lovers had padlocked engraved hearts and ribbons to it. The photo at the right shows a closer view.

We also saw miniature models of the structure for sale in shop windows as far away as Aveiro. I don't know whether it was created specifically to serve as padlocking space or whether the artist had something else in mind. I'm hoping the former—it's a great solution, allowing the padlockers to indulge their wishes without cluttering up or damaging some important permanent structure like a bridge.

Written 4 September 2015

Our final stop in Belém, the monastary of St. Jerome (São Jeronimo), in the left-hand photo, was clearly visible, just across the highway from where we stood, but the railroad runs down the median of the highway, complicating things. The bus had to take a surprisingly circuitous route to get there.

Our final stop in Belém, the monastary of St. Jerome (São Jeronimo), in the left-hand photo, was clearly visible, just across the highway from where we stood, but the railroad runs down the median of the highway, complicating things. The bus had to take a surprisingly circuitous route to get there.

As we finally drove up its driveway, we passed a long line of trees with these large, beautiful, orchid-colored flowers and large, entire leaves, which none of the guides was able to identify for me. From a distance, I thought Bauhinia, but they are clearly not. Anybody have a clue? Let me know if you'd like a larger version of the photo.

The old monastary now houses two museums, one of which is the National Museum of Archaeology, but we mainly visited the church and the cloister. I think the photo at the left is an arm of the transept and that the one on the right is the main apse, but I confess I may have mixed them up—so many of the side chapels are as spectacular as the main altar!

The old monastary now houses two museums, one of which is the National Museum of Archaeology, but we mainly visited the church and the cloister. I think the photo at the left is an arm of the transept and that the one on the right is the main apse, but I confess I may have mixed them up—so many of the side chapels are as spectacular as the main altar!

Construction of St. Jerome started in 1501 or 1502 and continued for 150 years. It was built mainly with profits from pepper imported from the east (thank you, Vasco da Gama). It's also in Manualine (baroque) style. The building was relatively little damaged by the earthquake, and collapsed areas have been restored.

The crossing of the nave and transcepts forms the largest vault in Portugal without a central support. The building also serves as a kind of pantheon. Many kings of Portugal are buried here. In fact, Manual's granddaughter knocked down the whole apse and replaced it with a larger one in a later and even more ornate architectural style that she felt was more appropiate for the royal tombs.

This is the place where the pastel de nata, often called the pastel de Belém, originated in 1837. The nuns used egg whites to starch their habits, so they had a whole heck of a lot of egg yolks left over. Two of the most successful uses they found for those are the pastel de nata and "ovos moles" (lesson: pronounced "o'-vosh," with two long o's, "mo'-lesh"), meaning "soft eggs," about which more later.

After an 1834 civil war between Princes Miguel (religious and absolutist) and Peter (secular and liberal), many religious orders were abolished because they sided with Miguel, and Peter won. Monks had to leave their monasteries immediately, but convents could persist until the last nun died of old age. The nuns at St. Jerome opened a bakery down the street from the church, which is still there and still producing the pastries—some of our group walked down there to buy some, though the guide assured us that the ones in the nearby snack bar came from the same place.

The panteon also includes the tombs of Portugal's greatest writers, thinkers, and heros. The one on the left here is of Portugal's greatest writer, Luís Vaz de Camões (pronounced "loo-eesh' vazh duh cah-mo-esh'"). He's not actually buried there, because the small church containing his grave was demolished before he became famous enough to be worth moving, so this tomb is empty and for commemorative purposes only. Maria the guide explained that all Portuguese school children must wade through a huge tome of his most important work at the age of 13 and 14, and the process is universally regarded as an ordeal.

The panteon also includes the tombs of Portugal's greatest writers, thinkers, and heros. The one on the left here is of Portugal's greatest writer, Luís Vaz de Camões (pronounced "loo-eesh' vazh duh cah-mo-esh'"). He's not actually buried there, because the small church containing his grave was demolished before he became famous enough to be worth moving, so this tomb is empty and for commemorative purposes only. Maria the guide explained that all Portuguese school children must wade through a huge tome of his most important work at the age of 13 and 14, and the process is universally regarded as an ordeal.

Others buried (or at least represented by tombs) there include Vasco da Gama, dos Passos, Fernando Passoa, and Alexandre Herculano.

The photo on the right just illustrates the elaborateness and detail of the Manualine and post-Manualine styles.

The guides particularly pointed out the tomb of King Sebastian I The Disastrous (they don't really call him that, but it's clearly the general opinion). He was highly inbred, rather unstable, and absolutely obsessed with converting the world to Christianity by military force. He overextended himself and got killed in North Africa in 1578, leaving Portugal without a royal heir. The Spanish kings stepped in, claiming they were next in line, Portugal lost its independence for 60 years, through Kings Filipe I, II, and III, and the Portuguese resent it profoundly to this day. Apparently Filipe I wasn't bad, but II and III were awful, and I was amazed how often "the Spanish interruption" (spoken with grinding of teeth) came up in subsequent tours and explanations.

The photo at the left shows how the columns and vault ribs in the church mimic the palm trees brought back by Portugal's explorers. Note also the "twisted" columns at the right-hand edge of the photo, betraying Moorish imfluence. We saw similar patterns on some of the columns in the cloister.

The photo at the left shows how the columns and vault ribs in the church mimic the palm trees brought back by Portugal's explorers. Note also the "twisted" columns at the right-hand edge of the photo, betraying Moorish imfluence. We saw similar patterns on some of the columns in the cloister.

The photo at the right shows the vault ribs in the cloister—not quite so palm-like but beautifully graceful.

The cloister was double. At the left is the view down into it from the upper level. Originally the center was occupied by a fountain and lush tropical vegetation, but all that was removed when the museums took over the buildings, because the humidity it generated was damaging the stone work of the columns.

The cloister was double. At the left is the view down into it from the upper level. Originally the center was occupied by a fountain and lush tropical vegetation, but all that was removed when the museums took over the buildings, because the humidity it generated was damaging the stone work of the columns.

From the upper level of the cloister, you can enter a loft above the nave of the church that allows a view down into the transept and houses the "upper choir," where the monks of the order sat in carved wooden stalls to chant, high above the altar and nave.

In the detail at the right, you can see a lovely little caravelle decorating one of the arches. I say little; it was probably the size of a dinner plate.

Our next stop was the very old waterfront neighborhood called Alfama (from the Arabic for place of abundant water, because it's on a hillside laced with springs). Both coming and going from Belém, we passed the 25 April bridge (left), which is a twin of the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, built by the same company immediately after they finished the Golden Gate. It opened in 1966. Before 1975 it was called the Salazar Bridge, for António de Oliveira Salazar, the economics professor who served as prime minister (read "dictator") of Portugal 1932 to 1968. After the Carnation Revolution, on 25 April 1974, it was renamed.

Our next stop was the very old waterfront neighborhood called Alfama (from the Arabic for place of abundant water, because it's on a hillside laced with springs). Both coming and going from Belém, we passed the 25 April bridge (left), which is a twin of the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, built by the same company immediately after they finished the Golden Gate. It opened in 1966. Before 1975 it was called the Salazar Bridge, for António de Oliveira Salazar, the economics professor who served as prime minister (read "dictator") of Portugal 1932 to 1968. After the Carnation Revolution, on 25 April 1974, it was renamed.

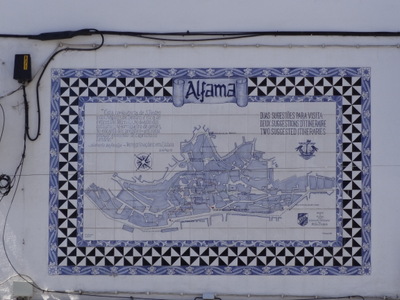

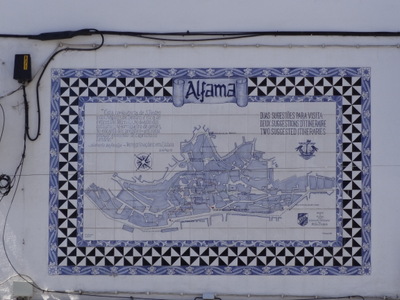

At the right is a panel of painted and glazed tile showing a street map of Alfama. We'd seen glazed tiles, on houses and elsewhere, but this was our real introduction to them. Portugal is famous for its glazed tiles, and many railroad stations and other public buildings are decorated with these multitile pictures.

Alfama is narrow and twisty throughout. At the left and right here, you can see typical streets. The ones parallel to the waterfront are more or less level; those that run at right angles to them tend to be so steep they must consist of steps. Our bus dropped us off at the bottom of the hill, and Maria handed the Quietvox transmitter off to a local city guide, who narrated our visit.

Alfama is narrow and twisty throughout. At the left and right here, you can see typical streets. The ones parallel to the waterfront are more or less level; those that run at right angles to them tend to be so steep they must consist of steps. Our bus dropped us off at the bottom of the hill, and Maria handed the Quietvox transmitter off to a local city guide, who narrated our visit.

Before the great earthquake of 1755, a series of smaller earthquakes began to make the local residents nervous, so those who could afford it moved to other areas and built larger houses, leaving those who couldn't to live in the tiny houses and apartments jammed together on the hillside. When the big one hit, all those new larger houses were demolished while Alfama rattled a little but remained pretty well intact—it's the only remnant of "old" Lisbon left. It's now a pretty fashionable place, but the apartments are to tiny many people are discouraged from living there, and some of the dwellings have been handed down from generation to generation, so it now houses quite a mix of ages and socioeconomic classes.

The photo at the left shows the interior of a public washhouse. In France, "laveries," outdoor public clothes-washing facilities, are considered antiques, are proudly decorated and displayed by small villages, and are no longer used. Here in Alfama, no one has room for a washer or dryer, so people still bring their laundry down to use these big tubs with built-in stone washboards.

The photo at the left shows the interior of a public washhouse. In France, "laveries," outdoor public clothes-washing facilities, are considered antiques, are proudly decorated and displayed by small villages, and are no longer used. Here in Alfama, no one has room for a washer or dryer, so people still bring their laundry down to use these big tubs with built-in stone washboards.

While we were there, lunchtime was approaching, and we saw several residents sitting on their stoops, firing up tiny charcoal grills in the middle of narrow pedestrian streets, preparing to grill their lunchtime sardines.

The rare open space shown at the right is the dooryard of St. Michael's church. I love the big planter for the palm. In sunny corners nearby, individual orange trees flourished. Around the corner from this square was the old Jewish section (one of three in the city), now undergoing renovation.

We were also shown a section of city wall from Moorish days, an "extension wall" built when the city outgrew its original walls.

St. Anthony of Padua was born in Alfama in 1185 (he only died in Padua). St. Vincent is Lisbon's patron saint and is celebrated annually, but only for a few days. In Alfama, St. Anthony is way more popular and gets a full month-long festival, centered on 12 June. The last vestiges of crepe paper still hung from overhead wires.

After Alfama, the buses took us back to the hotel and turned us loose for lunch. The photo at the left is a section of sidewalk opposite our hotel (between two tables in the antique market, which was still going on). Everywhere we went, the sidewalks were a mosaic of these light- and dark-colored little square paving stones (which are cubes rather than flat plates); the mosaics shown here were among the more elaborate.

After Alfama, the buses took us back to the hotel and turned us loose for lunch. The photo at the left is a section of sidewalk opposite our hotel (between two tables in the antique market, which was still going on). Everywhere we went, the sidewalks were a mosaic of these light- and dark-colored little square paving stones (which are cubes rather than flat plates); the mosaics shown here were among the more elaborate.

At the right is a view of a typical "basic" room at the Tivoli Lisboa. Lots of storage and very comfortable indeed.

Random things learned during the morning's tour

- The Moors brought sour oranges to Portugal, but the sweet orange came only in the 16th century from China, with the returning Portuguese explorers. The Christian reconquest of the Iberian peninsula took most of the 12th century.

- The Basilica de Estrella (pointed out to us from the bus) was the first ever "church of the sacred heart" and was built, starting in 1779, by a queen of Portugal who vowed to build it if God fulfilled her wish for a male heir. Alas, it took 11 years to build, and the poor little male heir didn't even live that long.

- Lisbon Tram 28 is recommended as good for sightseeing, though our tour escort recommended just taking a guided tour instead.

- Lisbon city center has a population of 600,000; greater Lisbon is 3 million; and all of Portugal about 10 million.

- Magellan was widely regarded in his day as a paragon of robust heath, because he never got scurvy, no matter how long the voyage. Once the cause and cure for scurvy became known (well after Magellan's time), the reason became clear—he loved marmalade and always packed along a sizeable stash of it for his personal use during the voyage.

- The lion is an attribute of St. Jerome.

But back to my account of the day.

We could have spent the afternoon exploring Lisbon on our own, but all four of us had signed up for the optional tile-museum tour, so we asked tour-director Miguel to recommend a quick restaurant nearby. He sent us to "Picasso," just up a side street beside the hotel, but we got there just as it was preparing to close—many businesses close at noon on Saturdays. So we got take-out sandwiches and pasteis de nata to eat in the hotel lobby. We all chose "carne asada" (roast meat), which in Mexican cuisine would be hot grilled strips of beef. What we got was tasty bread buns (some with seeds, some without) filled with cold roast white meat (either turkey or pork, probably the latter) and lettuce. They needed salt, which we added, and would have been better with some mayo, but they were very good just as is. Pasteis de nata for dessert, of course.

Written 10 September 2015

After our sandwiches and a leisurely coffee (for Buz and Kathy), which came with brightly colored macarooms, we reboarded bus C and set off to learn about tile and the Museu Nacional do Azulejo. "Azulejo" (pronounced ah-zoo-lay'-zhoo; note that "J" in Portuguese is pronounced "zh") is the Portuguese word for a flat square tile, and Portugal has been producing them in their millions and billions for five centuries. Starting in the 16th century, many houses were (and still are) entirely clad in them, and public buildings are, in addition, decorated with large multitile panels, each making up a single image, like the map of Alfama above, but way larger.

The cases shown in these two photos contain some of the oldest styles of tile, produced hundreds of years ago, before tile size was standardized (at about 7" square). The Moors favored geometrics, sometimes made up of mosaics of tiny tiles in a variety of shapes (some reminded me of quilting patterns), and sometimes (like those in the upper right corner in the left-hand photo) by a sort of batik technique, where lines were painted on the tiles in something hydrophobic, like linseed oil, and colored glaze was applied in the spaces between them. The hydrophobic lines kept the colors from spreading, and a chemical added to the oil (manganese oxide, I think they said) turned dark colored when the whole thing was fired, yielding a short of stained glass effect or colors outlined in black.

The cases shown in these two photos contain some of the oldest styles of tile, produced hundreds of years ago, before tile size was standardized (at about 7" square). The Moors favored geometrics, sometimes made up of mosaics of tiny tiles in a variety of shapes (some reminded me of quilting patterns), and sometimes (like those in the upper right corner in the left-hand photo) by a sort of batik technique, where lines were painted on the tiles in something hydrophobic, like linseed oil, and colored glaze was applied in the spaces between them. The hydrophobic lines kept the colors from spreading, and a chemical added to the oil (manganese oxide, I think they said) turned dark colored when the whole thing was fired, yielding a short of stained glass effect or colors outlined in black.

The right hand photo shows tiles formed when class was pressed into a mold that produced a raised pattern on the surface of the tile. Different-colored areas were outlined in slightly raised ridges that prevented the colors from spreading outside their alloted areas before firing.

The left-hand photo here shows the technique still used today for hand-painted tiles. Each tile is formed, dried, and dusted on the front with powdered glass mixed with tin oxide, then the desired pattern is painted on in aqueous suspensions of suitable pigments (the pigments don't necessarily look like the colors they will take on after firing). Once the painting is complete, the tile is fired at high temperature (really high, like 1000°C), and the powdered glass liquifies, floats to the top, and forms a smooth, clear glaze over the colored areas.

The left-hand photo here shows the technique still used today for hand-painted tiles. Each tile is formed, dried, and dusted on the front with powdered glass mixed with tin oxide, then the desired pattern is painted on in aqueous suspensions of suitable pigments (the pigments don't necessarily look like the colors they will take on after firing). Once the painting is complete, the tile is fired at high temperature (really high, like 1000°C), and the powdered glass liquifies, floats to the top, and forms a smooth, clear glaze over the colored areas.

As a guide, the artist can draw a pattern on heavy paper, pierce the paper along the pattern's outlines with a needle, lay the pierced pattern over the glass-dusted tile, and rub a bag of powdered charcoal over it, which produces little black dots outlining the pattern on the tile. The artist then paints between the lines, and the charcoal disappears in the firing process. The fuzzy object in the middle of the case is a rabbit's tail, used to brush off unwanted or mistaken charcoal dots. The whole technique is called "faience"; I've been looking at faience pieces in museums for years and never realized that it referred to the glazing technique (I associate it with French dishes made in the shape of food, like soup tureens in the shape of cabbages or pumpkins.) The tiles before dusting are a sort of pale beige, but once fired, the unpainted areas are bright white, presumably the color of fired tin oxide.

I think the large multicolored panel at the right above was produced by this technique.

The museum's exhibits include thousands of tiles and extensive explanations of the decorative influences on their colors, patterns, and uses. In addition to the large images made of of many tiles, each different, repeating patterns started to be used, because they could be produced much more economically. Typically, the pattern repeated over a block of four tiles, like the one in the left-hand photo here, which also shows the use of a border around the panel of tiles, a borrowing from the style of tapestries of the period.

The museum's exhibits include thousands of tiles and extensive explanations of the decorative influences on their colors, patterns, and uses. In addition to the large images made of of many tiles, each different, repeating patterns started to be used, because they could be produced much more economically. Typically, the pattern repeated over a block of four tiles, like the one in the left-hand photo here, which also shows the use of a border around the panel of tiles, a borrowing from the style of tapestries of the period.

China dishes brought back from Asia by the Portuguese explorers had a huge influence; a great many tiles, and especially the large images that decorate public buildings, are done entirely in blue and white, like the one shown here at the right.

Here are two takes on tile roses, displayed side by side. On the left, the roses are raised in relief—presumably the tiles were formed when clay was pressed into molds.

Here are two takes on tile roses, displayed side by side. On the left, the roses are raised in relief—presumably the tiles were formed when clay was pressed into molds.

At the right, the tiles are flat, and the pattern is entirely painted on rather than raised and painted over.

Note that both of these patterns repeat over a single tile, which is rotated to form a more elaborate arrangement.

At the left here is a particularly elaborate decorative piece—actually a single molded tile—presumably a portrait of someone, although I didn't get a photo of the label.

At the left here is a particularly elaborate decorative piece—actually a single molded tile—presumably a portrait of someone, although I didn't get a photo of the label.

At the right is a rather blurry photo of the largest single-image grouping of tiles known, which wrapped around three sides of a large room—sort of a faience Bayeux tapestry.

Like a surprising number of museums in Portugal, this one is located in an old convent (of which the country has a large supply). The photo at the left is of one of the convent's rooms, showing the beautiful inlaid wood floor, the blue-and-white tile panels on the walls, and (in the center) a four-sided reading stand. A book could be kept open on each side of it and the whole thing rotated for the reader's convenience.

Like a surprising number of museums in Portugal, this one is located in an old convent (of which the country has a large supply). The photo at the left is of one of the convent's rooms, showing the beautiful inlaid wood floor, the blue-and-white tile panels on the walls, and (in the center) a four-sided reading stand. A book could be kept open on each side of it and the whole thing rotated for the reader's convenience.

We also saw the beautifully decorated chapel and cloister. In the cloister, the recently restored capital of one of the small columns included a railway train! Restorers like to add little touches of their own to reflect the current era.

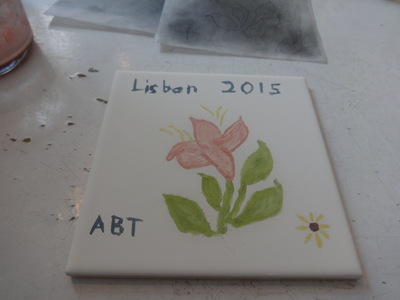

And at the right is, ta-da!, the pièce de résistance, our chance to paint our very own faience tiles!

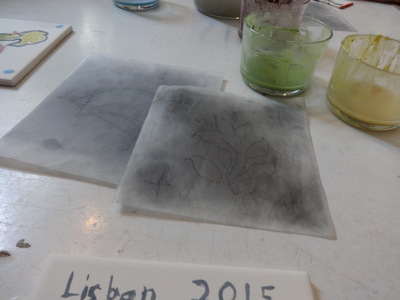

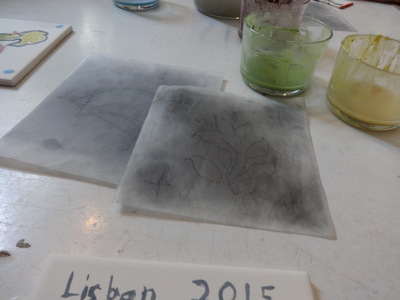

Tables were laid out with a place for each of us, already provided with a dried and glass-dusted tile and a paintbrush. Every few places was a group of glass dishes of pigment suspensions and a dish of water for rinsing brushes.

Tables were laid out with a place for each of us, already provided with a dried and glass-dusted tile and a paintbrush. Every few places was a group of glass dishes of pigment suspensions and a dish of water for rinsing brushes.

Step one was to lift the tile, by its edges, so as not to smudge the glass, and paint our names on the back so that we could keep everybody's straight.

At the right is a closer view of a couple of the patterns we were offered. I used the flower; David chose the sailboat. In the longer shot above, showing all three tables, you can see the little mesh bags of charcoal used to transfer the pattern to the tile. Dabbing didn't work; you had to hold the pattern in place and scrub the bag over it.

Here you can see David painting in the color between the faint gray lines of the pattern. We had to keep swirling and stirring the pigment dishes to get good coverage, because the pigment kept falling out of suspension, yielding washed-out colors.

Here you can see David painting in the color between the faint gray lines of the pattern. We had to keep swirling and stirring the pigment dishes to get good coverage, because the pigment kept falling out of suspension, yielding washed-out colors.

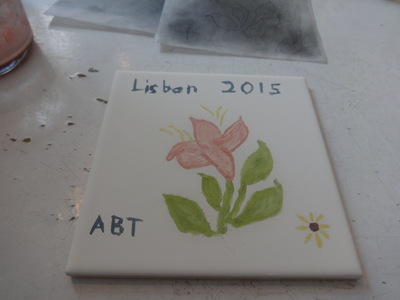

At the right is my tile, all painted and ready for firing. I had to go over parts of the flower several times to get the color as dark as I did. As you can see, it took a little practice to get the lines in the lettering straight; my initials and the date came out okay, but "Lisbon," where I started, is a little wonky.

We were told to leave our tiles where they were, on the table, and assured that they would be fired and delivered to us aboard the ship on the last day of our cruise.

Kathy speaks fluent Spanish, and a while back, while Buz worked with a colleague in Rio for a month, Kathy spent three weeks of the time taking an intensive Portuguese course, so her Portuguese is also quite good, but it's Brazilian Portuguese, pronounced very differently (and often with different vocabulary, like the word that means "teacup" in Portugal but "toilet bowl" in Brazil, or maybe the other way around). On our way out through the courtyard, I spotted a loquat tree, "neflier" in French, and wondered aloud what it was called in Portuguese. Kathy, right off the top of her head, said, "Oh, that's a loquat; "nispero" in Portuguese." It seems her one-on-one instructor in Rio was a plant enthusiast, and they spent a good portion of their daily afternoon conversational-practice session in the local botanical garden!

The bus got us back to the hotel by 5 p.m., and we agreed to meet Buz and Kathy at 7 p.m. to explore "restaurant street" in search of dinner.

As it happens, we never even got that far. At Ribadouro, a restaurant just a few doors down the street, Kathy spotted a dish on the posted menu that she loved and that I wanted to try, so we just ducked in there. Good choice.

As it happens, we never even got that far. At Ribadouro, a restaurant just a few doors down the street, Kathy spotted a dish on the posted menu that she loved and that I wanted to try, so we just ducked in there. Good choice.

I started with a shellfish soup, which consisted of a brown, (slightly too) cornstarch-thickened broth with bits of shrimp, lobster, and cockles in it and croutons on top.

Buz started with this terrific dish of clams steamed in olive oil with garlic and cilantro. Excellent! The soup was good, but I envied him those clams!

Buz started with this terrific dish of clams steamed in olive oil with garlic and cilantro. Excellent! The soup was good, but I envied him those clams!

David started with fried shrimp, which were excellent. They gave him so many that he was quite generous with samples. The pile of shrimp was flanked on both sides by heaps of fried leeksand deep-fried bread. The little dish of red stuff was just ketchup.

For our main course, Kathy and I both had pork Alentejo style (Alentejo is a large region that runs along the Spanish border inland from Lisbon)—cubes of fried pork tossed together with steamed clams and cubes of fried potato. I found the fried pork chunks pretty chewy and dry (though Kathy has yet to meet a pork dish she didn't like), but the clams (I would say Manila clams, maybe?) were excellent, and the separate fried potato cubes were very good. I ate most of the clams, and she ate most of the pork.

For our main course, Kathy and I both had pork Alentejo style (Alentejo is a large region that runs along the Spanish border inland from Lisbon)—cubes of fried pork tossed together with steamed clams and cubes of fried potato. I found the fried pork chunks pretty chewy and dry (though Kathy has yet to meet a pork dish she didn't like), but the clams (I would say Manila clams, maybe?) were excellent, and the separate fried potato cubes were very good. I ate most of the clams, and she ate most of the pork.

David and Buz both ordered a sort of hash of shredded potato, chunks of reconstituted dried salt cod, and scrambled egg. I thought it was great—David wasn't so sure. I was initially misled because at Brasserie Flo, we were served fresh cod, so I thought the Portuguese were using the same word—"bacalhau" (pronounced "bah-kahl-yow"; "h" after a consonant is pronounced like "y")—for both salt and fresh cod. In France, salt cod is "bacala" and fresh is "cabillaud," but Brasserie Flo used the word "bacalhau" because Portugal apparently doesn't even bother to have a word for fresh cod; nobody ever serves it. Bacalhau always means dried salt cod.

We couldn't finish all the food they brought, and we skipped dessert. Then straight home to the hotel. Breakfast opens at 6:30 a.m. (only for Viking folks; everybody else has to wait for the regular opening at 7), have your luggage ready for pickup just inside your room door by 7, bus leaves for Porto at 8:30 a.m.

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

The Tivoli's 7 a.m. breakfast buffet in the Brassierie Flo was gorgeous (and, even better, was included, together with the room, in our cruise price). At the left here is the cheese service—cubes of Brie in the foreground, and slices of various others behind. Dishes of fromage blanc, "cottage cheese" (not much like American cottage cheese), and honey to the side. At the back left, a platter of smoked salmon and a dish of lemon wedges (the capers and horseradish are hidden in this view).

The Tivoli's 7 a.m. breakfast buffet in the Brassierie Flo was gorgeous (and, even better, was included, together with the room, in our cruise price). At the left here is the cheese service—cubes of Brie in the foreground, and slices of various others behind. Dishes of fromage blanc, "cottage cheese" (not much like American cottage cheese), and honey to the side. At the back left, a platter of smoked salmon and a dish of lemon wedges (the capers and horseradish are hidden in this view).

Here, we have raw ham, cooked ham, poultry ham, paio (a Portuguese smoked sausage for slicing), and mortadella (the label was untranslated on this occasion, but on a restaurant menu in Aveiro, I saw mortadella translated as "spam").

Here, we have raw ham, cooked ham, poultry ham, paio (a Portuguese smoked sausage for slicing), and mortadella (the label was untranslated on this occasion, but on a restaurant menu in Aveiro, I saw mortadella translated as "spam"). Here's my first plate of breakfast: bacon, a small chicken sausage, a chocolate croissant, a raisin bun, an apple turnover, some smoked salmon, a little scrambled egg, and a slice of mortadella. I went back later for some smoked salmon. There was no cream cheese, so I spread fromage blanc on a slice of country bread, salted and peppered it, and put the salmon on top. Wow—a revelation! My new favorite way to eat smoked salmon.

Here's my first plate of breakfast: bacon, a small chicken sausage, a chocolate croissant, a raisin bun, an apple turnover, some smoked salmon, a little scrambled egg, and a slice of mortadella. I went back later for some smoked salmon. There was no cream cheese, so I spread fromage blanc on a slice of country bread, salted and peppered it, and put the salmon on top. Wow—a revelation! My new favorite way to eat smoked salmon.

After a short drive inland to circle the statue of Pombal while we listened to information about him, the bus headed for Belém, the oldest section of Lisbon, down on the waterfront. Our first stop was at this triangular memorial to those killed in the "overseas wars," the collective Portuguese name for the wars they fought in the 1960s, trying to retain all their former colonies. All the colonies became independent in 1974–75 (after the "carnation revolution") except Macao, which became independent in 1994). The little hut in front of it is one of a pair of sentry boxes (you can just see the edge of the second one at the left-hand edge of the photo). Two soldiers are always on guard there. The ones we saw were in camouflage fatigues, standing at parade rest. Every so often, they move—in our later photos they were standing under the monument itself rather than at the sentry boxes. The long white marble wall that surrounds the memorial on three sides is engraved with the names of all of those who died in the overseas wars (thousands and thousands).

After a short drive inland to circle the statue of Pombal while we listened to information about him, the bus headed for Belém, the oldest section of Lisbon, down on the waterfront. Our first stop was at this triangular memorial to those killed in the "overseas wars," the collective Portuguese name for the wars they fought in the 1960s, trying to retain all their former colonies. All the colonies became independent in 1974–75 (after the "carnation revolution") except Macao, which became independent in 1994). The little hut in front of it is one of a pair of sentry boxes (you can just see the edge of the second one at the left-hand edge of the photo). Two soldiers are always on guard there. The ones we saw were in camouflage fatigues, standing at parade rest. Every so often, they move—in our later photos they were standing under the monument itself rather than at the sentry boxes. The long white marble wall that surrounds the memorial on three sides is engraved with the names of all of those who died in the overseas wars (thousands and thousands). At our second stop (near a replica of the airplane used by two Portuguese to make the first aerial crossing of the south Atlantic—Portugal to Brazil— in 1922), we visited the emblematic Tower of Belém, also called the Tower of St.Vincent.

At our second stop (near a replica of the airplane used by two Portuguese to make the first aerial crossing of the south Atlantic—Portugal to Brazil— in 1922), we visited the emblematic Tower of Belém, also called the Tower of St.Vincent.

Next, again only a short distance away, the momument erected in the 1960s to Portugal's ocean-going explorers, who opened up most of the world to navigation. In distant view (left-hand photo) it is shaped like a stylized "caravelle," the kind of ship the explorers used, which was based on the Portuguese fishing vessel of the day.

Next, again only a short distance away, the momument erected in the 1960s to Portugal's ocean-going explorers, who opened up most of the world to navigation. In distant view (left-hand photo) it is shaped like a stylized "caravelle," the kind of ship the explorers used, which was based on the Portuguese fishing vessel of the day.

Set into the paving of the plaza in front of the monument is this huge map of the world with all of Portugal's colonies, territories, and possessions marked on it, together with their dates of discovery or annexation.

Set into the paving of the plaza in front of the monument is this huge map of the world with all of Portugal's colonies, territories, and possessions marked on it, together with their dates of discovery or annexation.

Also nearby was this structure made of heavy wire mesh and spelling out "LOVE." As is the vogue in so many places these days, lovers had padlocked engraved hearts and ribbons to it. The photo at the right shows a closer view.

Also nearby was this structure made of heavy wire mesh and spelling out "LOVE." As is the vogue in so many places these days, lovers had padlocked engraved hearts and ribbons to it. The photo at the right shows a closer view.

Our final stop in Belém, the monastary of St. Jerome (São Jeronimo), in the left-hand photo, was clearly visible, just across the highway from where we stood, but the railroad runs down the median of the highway, complicating things. The bus had to take a surprisingly circuitous route to get there.

Our final stop in Belém, the monastary of St. Jerome (São Jeronimo), in the left-hand photo, was clearly visible, just across the highway from where we stood, but the railroad runs down the median of the highway, complicating things. The bus had to take a surprisingly circuitous route to get there.

The old monastary now houses two museums, one of which is the National Museum of Archaeology, but we mainly visited the church and the cloister. I think the photo at the left is an arm of the transept and that the one on the right is the main apse, but I confess I may have mixed them up—so many of the side chapels are as spectacular as the main altar!

The old monastary now houses two museums, one of which is the National Museum of Archaeology, but we mainly visited the church and the cloister. I think the photo at the left is an arm of the transept and that the one on the right is the main apse, but I confess I may have mixed them up—so many of the side chapels are as spectacular as the main altar!

The panteon also includes the tombs of Portugal's greatest writers, thinkers, and heros. The one on the left here is of Portugal's greatest writer, Luís Vaz de Camões (pronounced "loo-eesh' vazh duh cah-mo-esh'"). He's not actually buried there, because the small church containing his grave was demolished before he became famous enough to be worth moving, so this tomb is empty and for commemorative purposes only. Maria the guide explained that all Portuguese school children must wade through a huge tome of his most important work at the age of 13 and 14, and the process is universally regarded as an ordeal.

The panteon also includes the tombs of Portugal's greatest writers, thinkers, and heros. The one on the left here is of Portugal's greatest writer, Luís Vaz de Camões (pronounced "loo-eesh' vazh duh cah-mo-esh'"). He's not actually buried there, because the small church containing his grave was demolished before he became famous enough to be worth moving, so this tomb is empty and for commemorative purposes only. Maria the guide explained that all Portuguese school children must wade through a huge tome of his most important work at the age of 13 and 14, and the process is universally regarded as an ordeal.

The photo at the left shows how the columns and vault ribs in the church mimic the palm trees brought back by Portugal's explorers. Note also the "twisted" columns at the right-hand edge of the photo, betraying Moorish imfluence. We saw similar patterns on some of the columns in the cloister.

The photo at the left shows how the columns and vault ribs in the church mimic the palm trees brought back by Portugal's explorers. Note also the "twisted" columns at the right-hand edge of the photo, betraying Moorish imfluence. We saw similar patterns on some of the columns in the cloister.

The cloister was double. At the left is the view down into it from the upper level. Originally the center was occupied by a fountain and lush tropical vegetation, but all that was removed when the museums took over the buildings, because the humidity it generated was damaging the stone work of the columns.

The cloister was double. At the left is the view down into it from the upper level. Originally the center was occupied by a fountain and lush tropical vegetation, but all that was removed when the museums took over the buildings, because the humidity it generated was damaging the stone work of the columns. Our next stop was the very old waterfront neighborhood called Alfama (from the Arabic for place of abundant water, because it's on a hillside laced with springs). Both coming and going from Belém, we passed the 25 April bridge (left), which is a twin of the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, built by the same company immediately after they finished the Golden Gate. It opened in 1966. Before 1975 it was called the Salazar Bridge, for António de Oliveira Salazar, the economics professor who served as prime minister (read "dictator") of Portugal 1932 to 1968. After the Carnation Revolution, on 25 April 1974, it was renamed.

Our next stop was the very old waterfront neighborhood called Alfama (from the Arabic for place of abundant water, because it's on a hillside laced with springs). Both coming and going from Belém, we passed the 25 April bridge (left), which is a twin of the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco, built by the same company immediately after they finished the Golden Gate. It opened in 1966. Before 1975 it was called the Salazar Bridge, for António de Oliveira Salazar, the economics professor who served as prime minister (read "dictator") of Portugal 1932 to 1968. After the Carnation Revolution, on 25 April 1974, it was renamed.

Alfama is narrow and twisty throughout. At the left and right here, you can see typical streets. The ones parallel to the waterfront are more or less level; those that run at right angles to them tend to be so steep they must consist of steps. Our bus dropped us off at the bottom of the hill, and Maria handed the Quietvox transmitter off to a local city guide, who narrated our visit.

Alfama is narrow and twisty throughout. At the left and right here, you can see typical streets. The ones parallel to the waterfront are more or less level; those that run at right angles to them tend to be so steep they must consist of steps. Our bus dropped us off at the bottom of the hill, and Maria handed the Quietvox transmitter off to a local city guide, who narrated our visit.

The photo at the left shows the interior of a public washhouse. In France, "laveries," outdoor public clothes-washing facilities, are considered antiques, are proudly decorated and displayed by small villages, and are no longer used. Here in Alfama, no one has room for a washer or dryer, so people still bring their laundry down to use these big tubs with built-in stone washboards.

The photo at the left shows the interior of a public washhouse. In France, "laveries," outdoor public clothes-washing facilities, are considered antiques, are proudly decorated and displayed by small villages, and are no longer used. Here in Alfama, no one has room for a washer or dryer, so people still bring their laundry down to use these big tubs with built-in stone washboards.

After Alfama, the buses took us back to the hotel and turned us loose for lunch. The photo at the left is a section of sidewalk opposite our hotel (between two tables in the antique market, which was still going on). Everywhere we went, the sidewalks were a mosaic of these light- and dark-colored little square paving stones (which are cubes rather than flat plates); the mosaics shown here were among the more elaborate.

After Alfama, the buses took us back to the hotel and turned us loose for lunch. The photo at the left is a section of sidewalk opposite our hotel (between two tables in the antique market, which was still going on). Everywhere we went, the sidewalks were a mosaic of these light- and dark-colored little square paving stones (which are cubes rather than flat plates); the mosaics shown here were among the more elaborate.

The cases shown in these two photos contain some of the oldest styles of tile, produced hundreds of years ago, before tile size was standardized (at about 7" square). The Moors favored geometrics, sometimes made up of mosaics of tiny tiles in a variety of shapes (some reminded me of quilting patterns), and sometimes (like those in the upper right corner in the left-hand photo) by a sort of batik technique, where lines were painted on the tiles in something hydrophobic, like linseed oil, and colored glaze was applied in the spaces between them. The hydrophobic lines kept the colors from spreading, and a chemical added to the oil (manganese oxide, I think they said) turned dark colored when the whole thing was fired, yielding a short of stained glass effect or colors outlined in black.

The cases shown in these two photos contain some of the oldest styles of tile, produced hundreds of years ago, before tile size was standardized (at about 7" square). The Moors favored geometrics, sometimes made up of mosaics of tiny tiles in a variety of shapes (some reminded me of quilting patterns), and sometimes (like those in the upper right corner in the left-hand photo) by a sort of batik technique, where lines were painted on the tiles in something hydrophobic, like linseed oil, and colored glaze was applied in the spaces between them. The hydrophobic lines kept the colors from spreading, and a chemical added to the oil (manganese oxide, I think they said) turned dark colored when the whole thing was fired, yielding a short of stained glass effect or colors outlined in black.

The left-hand photo here shows the technique still used today for hand-painted tiles. Each tile is formed, dried, and dusted on the front with powdered glass mixed with tin oxide, then the desired pattern is painted on in aqueous suspensions of suitable pigments (the pigments don't necessarily look like the colors they will take on after firing). Once the painting is complete, the tile is fired at high temperature (really high, like 1000°C), and the powdered glass liquifies, floats to the top, and forms a smooth, clear glaze over the colored areas.

The left-hand photo here shows the technique still used today for hand-painted tiles. Each tile is formed, dried, and dusted on the front with powdered glass mixed with tin oxide, then the desired pattern is painted on in aqueous suspensions of suitable pigments (the pigments don't necessarily look like the colors they will take on after firing). Once the painting is complete, the tile is fired at high temperature (really high, like 1000°C), and the powdered glass liquifies, floats to the top, and forms a smooth, clear glaze over the colored areas.

The museum's exhibits include thousands of tiles and extensive explanations of the decorative influences on their colors, patterns, and uses. In addition to the large images made of of many tiles, each different, repeating patterns started to be used, because they could be produced much more economically. Typically, the pattern repeated over a block of four tiles, like the one in the left-hand photo here, which also shows the use of a border around the panel of tiles, a borrowing from the style of tapestries of the period.

The museum's exhibits include thousands of tiles and extensive explanations of the decorative influences on their colors, patterns, and uses. In addition to the large images made of of many tiles, each different, repeating patterns started to be used, because they could be produced much more economically. Typically, the pattern repeated over a block of four tiles, like the one in the left-hand photo here, which also shows the use of a border around the panel of tiles, a borrowing from the style of tapestries of the period.

Here are two takes on tile roses, displayed side by side. On the left, the roses are raised in relief—presumably the tiles were formed when clay was pressed into molds.

Here are two takes on tile roses, displayed side by side. On the left, the roses are raised in relief—presumably the tiles were formed when clay was pressed into molds.

At the left here is a particularly elaborate decorative piece—actually a single molded tile—presumably a portrait of someone, although I didn't get a photo of the label.

At the left here is a particularly elaborate decorative piece—actually a single molded tile—presumably a portrait of someone, although I didn't get a photo of the label.

Like a surprising number of museums in Portugal, this one is located in an old convent (of which the country has a large supply). The photo at the left is of one of the convent's rooms, showing the beautiful inlaid wood floor, the blue-and-white tile panels on the walls, and (in the center) a four-sided reading stand. A book could be kept open on each side of it and the whole thing rotated for the reader's convenience.

Like a surprising number of museums in Portugal, this one is located in an old convent (of which the country has a large supply). The photo at the left is of one of the convent's rooms, showing the beautiful inlaid wood floor, the blue-and-white tile panels on the walls, and (in the center) a four-sided reading stand. A book could be kept open on each side of it and the whole thing rotated for the reader's convenience.

Tables were laid out with a place for each of us, already provided with a dried and glass-dusted tile and a paintbrush. Every few places was a group of glass dishes of pigment suspensions and a dish of water for rinsing brushes.

Tables were laid out with a place for each of us, already provided with a dried and glass-dusted tile and a paintbrush. Every few places was a group of glass dishes of pigment suspensions and a dish of water for rinsing brushes.

Here you can see David painting in the color between the faint gray lines of the pattern. We had to keep swirling and stirring the pigment dishes to get good coverage, because the pigment kept falling out of suspension, yielding washed-out colors.

Here you can see David painting in the color between the faint gray lines of the pattern. We had to keep swirling and stirring the pigment dishes to get good coverage, because the pigment kept falling out of suspension, yielding washed-out colors.

As it happens, we never even got that far. At Ribadouro, a restaurant just a few doors down the street, Kathy spotted a dish on the posted menu that she loved and that I wanted to try, so we just ducked in there. Good choice.

As it happens, we never even got that far. At Ribadouro, a restaurant just a few doors down the street, Kathy spotted a dish on the posted menu that she loved and that I wanted to try, so we just ducked in there. Good choice.

Buz started with this terrific dish of clams steamed in olive oil with garlic and cilantro. Excellent! The soup was good, but I envied him those clams!

Buz started with this terrific dish of clams steamed in olive oil with garlic and cilantro. Excellent! The soup was good, but I envied him those clams!

For our main course, Kathy and I both had pork Alentejo style (Alentejo is a large region that runs along the Spanish border inland from Lisbon)—cubes of fried pork tossed together with steamed clams and cubes of fried potato. I found the fried pork chunks pretty chewy and dry (though Kathy has yet to meet a pork dish she didn't like), but the clams (I would say Manila clams, maybe?) were excellent, and the separate fried potato cubes were very good. I ate most of the clams, and she ate most of the pork.

For our main course, Kathy and I both had pork Alentejo style (Alentejo is a large region that runs along the Spanish border inland from Lisbon)—cubes of fried pork tossed together with steamed clams and cubes of fried potato. I found the fried pork chunks pretty chewy and dry (though Kathy has yet to meet a pork dish she didn't like), but the clams (I would say Manila clams, maybe?) were excellent, and the separate fried potato cubes were very good. I ate most of the clams, and she ate most of the pork.