After lunch we just went back to the hotel, where David practiced his talk. Then it was off to the train station to go to Porto for the conference dinner. On the way, we passed the interesting piece of street art shown in the left-hand photo.

After lunch we just went back to the hotel, where David practiced his talk. Then it was off to the train station to go to Porto for the conference dinner. On the way, we passed the interesting piece of street art shown in the left-hand photo. Wednesday, 2 September 2015: Excursion to Porto

Written 14 June 2016

The meiofauna meetings ran only a half day on Wednesday, to allow time for sightseeing and the meeting excursion—a cellar tour and dinner at the Taylor's port lodge in Porto (well, actually in Gaia, on the bank opposite Porto).

We sightseers got a late start and decided just to take it easy until until lunch time. I worked on the, which at the time was on still on the Lisbon segment of the trip.

David and Buz came back with box lunches from the meeting, but we thought we could do better. Kathy and Buz sent to some place she had in mind, and David and David and I went back to the fish market restaurant, where he got the grilled robalo that I had had last time, and I had the monkfish-and-prawn skewer that Kathy had the last time.

After lunch we just went back to the hotel, where David practiced his talk. Then it was off to the train station to go to Porto for the conference dinner. On the way, we passed the interesting piece of street art shown in the left-hand photo.

After lunch we just went back to the hotel, where David practiced his talk. Then it was off to the train station to go to Porto for the conference dinner. On the way, we passed the interesting piece of street art shown in the left-hand photo.

We missed the train we intended to take but took the next and managed to get there just in time (passing through Estarreja, Avanca, Ovar, and Esmoriz, among others, on the way). The walk from the train station to Taylor's was a little complicated (not to mention steep!), but students were posted on strategic street corners to keep us on the route.

In the right-hand photo David poses with a colleague on the sidewalk.

Inside the gate, this stairway led down into the garden courtyard of the port lodge. The vegetation overhead is grapevines.

Inside the gate, this stairway led down into the garden courtyard of the port lodge. The vegetation overhead is grapevines.

The courtyard was planted with fruit trees as well as ornamentals. These pears were ripening overhead.

Boxwood hedges and rose beds took up most of the space, but they were punctuated with the bright double-flowered azalea, as well as wistaria and a weeping willow.

Boxwood hedges and rose beds took up most of the space, but they were punctuated with the bright double-flowered azalea, as well as wistaria and a weeping willow.

A pair of peacocks wandered around, hoping someone would drop a potato chip.

Tables were already set inside for our dinner, and the view from the terrace was magnificent.

Tables were already set inside for our dinner, and the view from the terrace was magnificent.

We were definitely there at the right time for fruit. Grapes were ripening on all the arbors surrounding the courtyard garden.

We were definitely there at the right time for fruit. Grapes were ripening on all the arbors surrounding the courtyard garden.

When our group's turn came, we got to follow our guide (shown here at the right) into the cellars for a tour and explanation of the port-making process.

If I read my notes correctly, Taylor's was founded in 1692. Like many port houses, it has an English name because the English, searching for a replacement for claret because they were at war with France, came to Portugal and founded port houses.

I think they said that Taylor's produces 40 million liters of wine a year, but perhaps that the whole port region? Anyway, they aim for a finished produce that contains 120 g of sugar per liter—that is, a wine that's 20% sugar and 20% alcohol.

Taditionally, port vines are planted wider apart than most and are only a meter tall. During the harvest, women cut the grapes, and men carry 40-kg baskets of them down the mountains. White and red grapes are both used but never mixed, even to make rosé. As we had learned elsewhere, the wine was made upriver, at the vinyards, then shipped downriver to the port lodges for blending, aging, etc. Originally, the barrels were only partly filled and were roped together fro shipping. That way, if the boat came to grief in the rapids (this was before the locks, of course), the barrels would float and would stay together so that they could be snagged and hauled back aboard when the boat was righted.

Although Porto gave its name to the wine, everyone built their port lodges in Gaia because Porto was under church control. Gaia wasn't and therefore presented a much better tax and regulatory climate.

The master blender at Taylor's is David Guimareis.

The master blender at Taylor's is David Guimareis.

All of Taylor's wines are still actually crushed by foot treading. The stems are left on for that first crush. The guide explained that tourists who arrive during the harvest are always eager to help with the treading but they never last long. The job is strenuous and goes on for hours (it has to be done all in one go). It also requires that the treaders form a line with their arms on each others' shoulders and work in a steady rhythm, without tripping each other or stopping.

In particularly good years, a "vintage" port is produced. Only red ports are ever vintage. In years that are not quite up to vintage quality, LBV (late-bottled vintage) wine is produced. It stays in the barrel for four years, then is filtered and bottled and is ready to drink. Vintage is better than LBV; extra aging in the bottle, not the barrel, makes a big difference.

Small casks are called "pipes" (we had always wondered about references in British literature to the "pipes" of port laid down by new fathers for their sons). Large ones are called "vats." Taylor's uses only French oak for their casks and barrels. Young wines are kept in large vats, because they get less wood contact. They spend five years in the large barrels, then are bottled and sold. They are made in ruby, whites, and rosť (reds from which the skins have been taken off early).

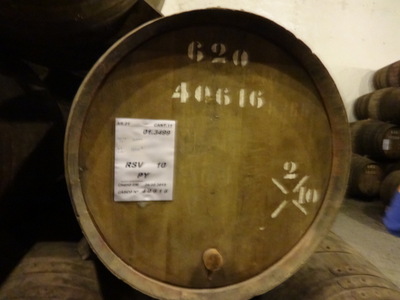

The guide also explained the notations on the barrels, but I didn't get all of it. She said that 2 liters is considered one man-day worth of port (did she say it was called a "canada"?). The English pipe is only 550 liters, but I think the one shown here is 620 liters. The 5-digit number is a secret code for the grape(s) used that only the master blender can read.

After the tour, we were shown back to the courtyard to wait for dinner while others took the tour. The right-hand above shows some of the hors d'oeuvres that were being passed. Clockwise from the bottom they are ordinary potato chips, a small square dish of green-brown olives, little squares of a quichy kind of thing with vegetable bits embedded in it, a row of cod-stuffed peppers alternating with more quichy squares, a glass dish of fritters coated with black and white sesame seeds, and porcelain spoons filled with couscous tabouleh. The empty dish in the center with the smaller upturned dish on top held napkins. The upturned dish rested on top of them to keep them from blowing away. A saxophonist provided quiet background music.

Here's the centerpiece on our dinner table; every table had a different one.

Here's the centerpiece on our dinner table; every table had a different one.

Each of us was served a crusty bread roll; butter packets were already on the table.

The first course was broccoli soup with a large mushroom ravioli in the bottom of the bowl and little cheese-biscuit croutons floating on top. Very good.

The first course was broccoli soup with a large mushroom ravioli in the bottom of the bowl and little cheese-biscuit croutons floating on top. Very good.

The main course, shown at left, was listed on the menu as "the chef's codfish." It was squares of a sort of casserole consisting of a layer of greens on the top, a middle layer of shredded salt cod with onions and some potato, and a top layer of crumbs and olive chunks. Not bad, but not really an improvement on other code preparations we've had.

After the main course, we were treated to another fado concert featuring the usual instruments and this young singer.

After the main course, we were treated to another fado concert featuring the usual instruments and this young singer.

Dessert was crème brulée topped with a sweet cinnamon crisp. With dinner, we were offered a "vino verde" (a light greenish white wine made locally) and red and white wines from the region (the red was from Romariz, one of the places we passed through on the train ride), but with dessert they served (of course) one of their own white ports, Fonseca Bin 27.

After dinner, I got these shots of the city of Porto by night, from the terrace just outside the dining room. At the right is the Bishop's Palace, and at the left the round church (the one reached by cable car.

After dinner, I got these shots of the city of Porto by night, from the terrace just outside the dining room. At the right is the Bishop's Palace, and at the left the round church (the one reached by cable car.

And here is a wider shot incorporating both, together with the illuminated bridge over the Douro.

And here is a wider shot incorporating both, together with the illuminated bridge over the Douro.

Chocolate almond cookies were served with after dinner coffee while we waited for the bus that the conference organizers provided to take us back to Aveiro. David and I caught the first bus and arrived back at the hotel about midnight.