Wednesday, 2 August, Moscow: museums (but not all the same ones) and the city by night

Written 25 August 2017

From the start, we regarded Wednesday, 2 August (or "Day 3" as the Viking website billed it) as our busy day, and we were right, despite my voluminous description of Tuesday's activities. Wednesday certainly offered the greatest proliferation of mutually exclusive choices, all of which I would have liked to see!

In the end, for the morning excursion, Rachel, David, and I all chose the Tretyakov Gallery over the visit to Sergiev Posad (Russia's greatest monastery). Ev decided to sleep in and stayed on the ship. The afternoon presented an even harder choice. David and I chose the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Rachel the Moscow Jewish Museum, and Ev the Cosmonaut Museum, so when we picked up our landing cards, we received three different group assignments and dispersed across the city in separate buses.

We all also opted for the "Moscow by Night" excursion, scheduled to end at 12:30 a.m., even knowing we were booked for an 8:30 excursion Thursday morning! We could, of course, have instead stayed on the ship for the evening entertainment with the ship's musicians (Sigmund on keyboards and Elena on vocals, neither of whom I liked as well as the sole musician on the 2015 cruise).

But to begin at the beginning. I paused before going out to breakfast to photograph this handy little reading light above my bed, with my hand in the shot for scale. Flush with the headboard, it was turned off, but if you used a finger to push on the little round recess below the light, it rotated out of its socket, lit up, and could be swiveled to the desired angle. It was equipped with very bright LED elements. To turn it off, you just pushed it back into position, flush with the headboard.

But to begin at the beginning. I paused before going out to breakfast to photograph this handy little reading light above my bed, with my hand in the shot for scale. Flush with the headboard, it was turned off, but if you used a finger to push on the little round recess below the light, it rotated out of its socket, lit up, and could be swiveled to the desired angle. It was equipped with very bright LED elements. To turn it off, you just pushed it back into position, flush with the headboard.

The breakfast buffet was substantially the same each morning, but details changed from day to day. We were always offered about four cold cuts, but different ones on different days. On this day, a couple of them looked like cold roast beef and cold roast pork. The day's sausage choice was much better; it resembled kielbasa with chunks of cheese embedded in it. Still not what I would think of as a breakfast sausage, but tasty. The canary melon had been replaced with canteloupe, but it reappeared later in the week. The chef had added tiny strawberry-yogurt milkshakes, and the chafing dish that usually contained some sort of cooked grain was filled instead with a yummy, soupy corn-beef-hash-like substance in a broth so rich it congealed on the plate as it cooled. Alas, it never reappeared in the course of the cruise. The cheese assortment had also changed.

Then it was off to the buses for the trek back into central Moscow. At the left here, David and Rachel pose by the bow of our ship. The Cyrillic lettering over their heads transliterates as "Viking Akun."

Then it was off to the buses for the trek back into central Moscow. At the left here, David and Rachel pose by the bow of our ship. The Cyrillic lettering over their heads transliterates as "Viking Akun."

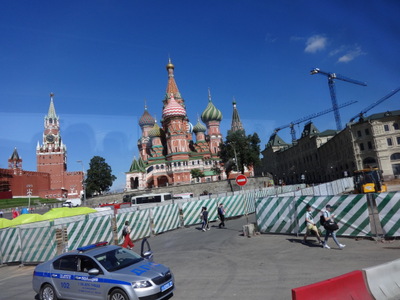

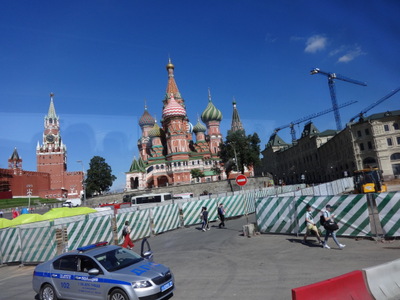

Our route led us around the Kremlin and over the Moscow river. At the left is a view of St. Basil's from the other side. That is, from this side, Red Square is behind it. The barricades between it and the camera are a propos of the annual National Festival of Paratroopers, which is celebrated on 2 August. Red Square is closed so that (according to our local guide, whose father was a paratrooper) the paratroopers can drink champagne and swim in the fountains. You can spot them by their blue berets and drunken behavior, she told us.

As I mentioned when I described Red Square, the first wall of the Kremlin, which borders the square, continues past St. Basil's; you can see it to the left of the cathedral. In the shot to the right, you see it reach the southeast corner. The tallest onion dome behind it is the Delphian tower, where the Tsar bell was to have hung (the bell now rests near its foot).

As I mentioned when I described Red Square, the first wall of the Kremlin, which borders the square, continues past St. Basil's; you can see it to the left of the cathedral. In the shot to the right, you see it reach the southeast corner. The tallest onion dome behind it is the Delphian tower, where the Tsar bell was to have hung (the bell now rests near its foot).

At this corner, the wall takes a sharp turn to the right and runs along the Moscow River, as you can see in the right-hand photo.

Here, at the right, Rachel poses in front of the gates of the Tretyakov Gallery. The gallery actually occupies two buildings some distance apart, but we visited only the old one—just as well, as the new one displays newer art, less to our taste.

The photo at the left is of a very famous portrait of Paul I, only son of Catherine the Great (and not one of the most successful tsars). It was pointed out to us as the first example of a royal portrait without an opulent background to reinforce the importance of the subject. Paul's haughty expression clearly says that he thought his importance spoke for itself.

The museum is the family home of Pavel Tretyakov (born 1832) and his brother Sergei, who were born to a wealthy family. The two inherited the family linen business and continued to prosper.

Pavel painted himself but only as an amateur. As a collector he confined himself to Russian artists and had very good taste. Sergei collected European artists as well. They acquired the first three pictures in 1856.

Pavel was both a very good employer and a major patron of the arts. He supported artists in financial need and looked after their families if they were incapacitated or died. He was so popular in the artistic community that he was generally given first refusal on new works. At his linen mills, he was the first in Russia to inhtroduce the 8-hour work day. He built schools and hospitals for his workers and gave pensions to their widows.

He married late but happily and had six kids, four girls and two boys. He lost his youngest son (age 9) and his brother Sergei in quick succession. As Sergei had requested, Pavel gave Sergei's collection to Moscow. Then in 1892, he gave the city his own collection and the house, where he continued to live and serve as curator and docent until he died in 1898. A condition of both gifts was that the collection be kept and exhibited together.

The collection was hidden during World War II, but it reopened promptly in 1945. The collection now consists of 150,000 pieces.

As the guide explained, before Peter the Great, Russian painting was confined entirely to the production of icons (which we were informed were not painted but "written" and not looked at but "read"). Peter visited western Europe and brought back both paintings and artists, as did the merchants and nobles he encouraged to travel abroad. He also sent Russian artists to western Europe to study.

Icons protrayed only religious subjects whose appearance could only be imagined. Between iconography and real protraiture was a stage called "persona paintings"—images that portrayed real people, historical or contemporary, without necessarily actually resembling them. Only after that did artists start painting portraits intended to show what the subject looked like. For example, of two protraits we were shown, that of the Empress Anna Ivanovna does not resemble her, whereas Empress Elizabeth's does.

Eventually artists starting painting portraits with actual action and personality rather than stiff, motionless protrayals. An early example we were shown was of a wealthy merchant (P. A. Demidov) whom D. G. Levitsy protrayed with a watering can, proudly exhibiting some of his exotic plants.

The Mongol occupation held Russia back for a good while, so the Renaissance ran late there, but once Peter the Great started encouraging the process, Russia caught up in about 50 years with what western Europe had been developing for about 300. The guide said that Russian artists didn't introduce much new to the art world, except for the avant-garde, which we were not seeing that day.

Once portraiture got going, it flourished. At the left here is a very famous portrait of Alexander Pushkin painted by O. A. Kiprensky. We were repeatedly assured that Pushkin is to Russian poetry and literature what Shakespeare is to English poetry and literature.

Once portraiture got going, it flourished. At the left here is a very famous portrait of Alexander Pushkin painted by O. A. Kiprensky. We were repeatedly assured that Pushkin is to Russian poetry and literature what Shakespeare is to English poetry and literature.

At the right, is a portrait of M. I. Lopukhina in which V.L. Borovikovsky might have carried the trend a little too far. I'm surprised the lady's father or brother didn't call him out!

As always seems to happen in literature and art, a group of artists decided to start painting ordinary people and situations rather than the aristocracy. And as usual, they were soundly rejected by the establishment. In Russia, the called themselves the "itinerants" and traveled around as a group, exhibiting their work where they could. We were shown an early example, Ploughing in Spring, in which A. G. Venetsianov clearly had his heart in the right place but didn't know much about his subject. He portrayed a peasant woman strolling across a field, leading a pair of horses dragging a plough (it looks like a harrow to me), barefoot, and wearing her Sunday best.

After a school of "realists" emerged, yet another group, called "critical realists" showed up. Their paintings, besides being realistic, were intended as social criticism. In the example at the left, by V. G. Perov, three children struggle to haul a barrel of water. The boy who modeled for the central figure died shortly thereafter, and his mother came to the artist to try to buy the painting, the only image of her son, but it had already been sold to a private collector (presumably Tretyakov).

After a school of "realists" emerged, yet another group, called "critical realists" showed up. Their paintings, besides being realistic, were intended as social criticism. In the example at the left, by V. G. Perov, three children struggle to haul a barrel of water. The boy who modeled for the central figure died shortly thereafter, and his mother came to the artist to try to buy the painting, the only image of her son, but it had already been sold to a private collector (presumably Tretyakov).

In the one at the right, one hunter regales two others with tales of his exploits. The older listener is clearly skeptical, but the younger one is enthralled.

Another, not shown here, protrayed a bride clearly not very happy at being married off to an elderly man.

I took many, many photos to remind myself of what I saw, but unfortunately, the glass over the paintings created constant glare, so most of them are not suitable for presentation here. And some, such as a famous painting of a nude Bathsheba with a black servant, are unsuitable for upload for family viewing.

Written 29 August 2017

On our way through the museum, we passed through innumerable schools of art, including a room full of the "orientalism" we've seen elsewhere, when Europe became fascinated by Egypt and the world beyond Suez.

On our way through the museum, we passed through innumerable schools of art, including a room full of the "orientalism" we've seen elsewhere, when Europe became fascinated by Egypt and the world beyond Suez.

Only at the end of the tour did we do a pass through the rooms of Russian icons. These two depict two of the three ways the madonna is traditionally protrayed. Images in which she is shown cheek-to-check with Jesus, as in the left-hand image, are called "tenderness." Those in which Jesus is presented face-on to the viewer against her body (as in the right-hand image) are called "orans." Those in which she points or gestures toward Jesus (not shown here) are called "showing the way."

The right-hand photo also shows a style in which a central icon is surrounded by a series of smaller images that tell a story (in this case, the life of Christ from annunciation at the upper left to resurrection at the lower right), like the panes of a stained glass window.

At this point came a parting of the ways. Rachel wanted to see the Jewish Museum more than she wanted to see the Pushkin, but that didn't mean she didn't also really, really want to see the Pushkin. Meanwhile, another couple on the tour, also signed up for the Pushkin in the afternoon, were ancient-history buffs and really, really wanted to see the Gold of Troy, which is at the Pushkin, but they had checked with the guides and learned that that section wasn't included in our tour of the place. They therefore proposed skip the bus ride back to the ship for lunch and then back into town and instead to set off on foot, cross-country, to the Pushkin, to see the Gold of Troy over the lunch break, then rejoin us there for the afternoon tour. Rachel jumped at the chance to go with them. She would then catch a taxi from the Pushkin to the Jewish Museum in time to join the tour there. They explained all this to our tour guide, who consulted by phone with all the other tour guides so that everybody knew what was going on, handed me the sack of books she'd just bought in the gift shop, and disappeared over the horizon.

The rest of us got back on the bus and headed for lunch. On the way, we passed this bridge, which is the designated location in Moscow for the attachment of romantic padlocks. The big flowered heart (with the inevitable tourist posing in front of it in a bright green shirt) marks the entrance to the bridge. Just above her head and just below the point at the top of the heart, you can see a blurry, christmas-tree like object, which is a metal mesh tree covered with red-beribboned romantic padlocks. The bridge bears several of these metal trees.

The rest of us got back on the bus and headed for lunch. On the way, we passed this bridge, which is the designated location in Moscow for the attachment of romantic padlocks. The big flowered heart (with the inevitable tourist posing in front of it in a bright green shirt) marks the entrance to the bridge. Just above her head and just below the point at the top of the heart, you can see a blurry, christmas-tree like object, which is a metal mesh tree covered with red-beribboned romantic padlocks. The bridge bears several of these metal trees.

I also got this shot of the three-times-life-size status of Vladimir of Kiev arriving to baptize Russia in the 10th century.

Things we learned on the way:

- Peter I's daughter Elizabeth founded the Academy of Fine Art.

- One of the buildings we passed was the Lublyanka Prison, but I didn't get a good photo.

- The guide says that, throughout the city, the mayor is ignoring traffic problems and instead replacing tiles and curbs and widening sidewalks because his wife manufactures tiles. Everyone is annoyed about that.

- Anna Ivanovna's crown is the one with 2500 diamonds.

- It's now illegal to build a private house in Moscow. You have to live in an appartment.

- We passed a rack of metro rental bikes, much like the ones in Paris and other large cities.

On this ride, and on many others, we passed this underground shopping mall. It is lit by a whole collection of domed skylights, of which this is the largest. I tried several times to get a better photo of it, but the bus just wasn't quite high enough. What's special about this dome is that it functions as a clock, rotating slowly throughout the day. It's decorated with half of a map of the world, so that you can see what time it is in different cities, and the ocean areas are decorated with constellations of stars. That's the State Museum and a tower of the Kremlin wall behind it.

On this ride, and on many others, we passed this underground shopping mall. It is lit by a whole collection of domed skylights, of which this is the largest. I tried several times to get a better photo of it, but the bus just wasn't quite high enough. What's special about this dome is that it functions as a clock, rotating slowly throughout the day. It's decorated with half of a map of the world, so that you can see what time it is in different cities, and the ocean areas are decorated with constellations of stars. That's the State Museum and a tower of the Kremlin wall behind it.

When we got back to the ship, lunch was waiting. From the appetizer/salad bar, I got this smoked-salmon canape with an onion ring on top. Other choices were chili con carne and braised celery and chicory with balsamic drizzle.

David and I both chose the pork steak with BBQ sauce, country potatoes, and green beans wrapped in bacon.

David and I both chose the pork steak with BBQ sauce, country potatoes, and green beans wrapped in bacon.

Ev, still a little stunned that he'd sent his wife off with us and gotten back nothing but a sack of books, had the "croque monsieur" (a French grilled ham-and-cheese sandwich that the chef had probably read about but never seen an example of). Nobody opted for the vegetarian carrot soup.

The dessert choices were lemon cheesecake and "Belle Helène" (pear, vanilla ice cream, and chocolate sauce), but we didn't have time for either one. We hopped back on the buses and headed for our respective museums.

Surprisingly, only four other people were on the bus to the Pushkin. We met the two others there (the ones who had gone directly, with Rachel). Impressionists are usually a big draw, so I expected more. For the record, the museum has nothing whatever to do with Pushkin the poet; Russians just like naming things after him.

Surprisingly, only four other people were on the bus to the Pushkin. We met the two others there (the ones who had gone directly, with Rachel). Impressionists are usually a big draw, so I expected more. For the record, the museum has nothing whatever to do with Pushkin the poet; Russians just like naming things after him.

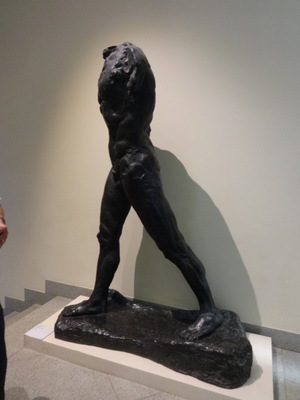

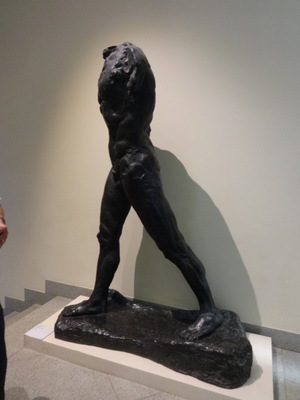

As soon as we entered the museum, I was greeted at the top of the first flight of stairs by an old friend—Rodin's Walking Man, one exemplar of which graces the Smith College campus and which I have since encountered in several other venues, including the Rodin museum in Paris. As soon as I got these two photos of it, my camera battery died, and like a dunce, I had left the spare in my purse on the bus! Drat.

That stair landing displayed several other Rodins (including a single Burger of Callais, a study for the larger group) and a quartet of Maillols.

The idea for the Pushkin Museum came from a professor at Moscow University. Ivan Tsvetaev. (He was also the father of a famous female Russian poet, Marina Tsvetaeva.)

He felt it was important because Russian students didn't have the chance to travel abroad to see great art works. He set about fund raising, and he had plaster casts made of famous sculptures as a start, so that students could visit and study them.

In 1912, the museum finally opened. In 1948, it acquired around 300 paintings and over 60 works of sculpture of the late 19th century and the first third of the 20th, the collections of Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin.

Also in 1948, social tendencies appeared around the campaign against formalism (something about museums of western art); everything was packed up indiscriminately in unlabeled crates and sent to the Hermitage. After Stalin's death efforts were made ot reinstate it. Only in the 1990's were the boxes opened; the art was divided in a very haphazard way, half was given to the Hermitage and the other half back to the Pushkin in Moscow, so what we saw was only half of the collection as it existed in 1948.

Apparently, Moscow is now organizing a "museum town" to bring everything together. I'm not sure what that means; perhaps it will just be a tight cluster of museums with a pedestrian area in and around it, like the one in Houston.

The museum was great, and I wish I'd been able to take photos. Here's some of the stuff we saw, roughly in the order we saw it:

- A plaster version of the famous screaming "Marseillaise" by Francois Rude.

- An Ingres Virgin with Chalice, with Alexander Nievski and St. Nicholas standing in the background.

- A Goya Portrait of a Lady (possibly Lola Jimenez)—the only Goya they have

- A collection of Daumiers, including the laundress on the stairs.

- Delacroix, After a Shipwreck.

- A whole room of the Barbizon school.

- Several rooms full of Corots,

- Some Manets, looking unfinished (in fact, some of them are unfinished). A Manet portrait of Antonin Proust (Marcel's uncle, a good friend of Manet).

- A small Rodin in just about every room: e.g., bust of Victor Hugo, Running Away, Eternal Spring; the Kiss.

- Several Degas: ballerinas, a group of horses; a group of ballerinas who might all be the same one "double exposed" as it were. Bust of Gustav Mahler.

- A couple of Pissaros, including a Boulevard des Capucines in the snow.

-

A room of Renoirs; his famous portrait of Jeanne Samary in a green dress, head and shoulders only (the full-length view is at the Hermitage). Very colorful and with a colorful background instead of dark. In the Garden under the Trees of the Moulin de la Galette (woman in a striped dress with a blue sash). David took a few photos, which I use two of here, but he didn't photograph the labels, so I can't confidently attribute the others.

A room of Renoirs; his famous portrait of Jeanne Samary in a green dress, head and shoulders only (the full-length view is at the Hermitage). Very colorful and with a colorful background instead of dark. In the Garden under the Trees of the Moulin de la Galette (woman in a striped dress with a blue sash). David took a few photos, which I use two of here, but he didn't photograph the labels, so I can't confidently attribute the others.

- Some art glass: lovely jar with a jackdaw on it, some fennecs, a jaguar.

- A room of Monet, including some especially good water lilies and a couple of Rouen cathedrals; haystack at Giverny.

- A couple of Sissleys.

A room of mostly Cezanne; Pierrot and Harlequin; a plate of apples and some pears on a dishcloth.

A room of mostly Cezanne; Pierrot and Harlequin; a plate of apples and some pears on a dishcloth.

- A case of six small table-top Maillols.

- Just two Toulouse-Lautrec pastel sketches on brown paper

- Van Goghs and Gaugins together in a room with the Toulouse-Lautrecs (including the one painting that was sold during Gaugin's lifetime (something at Arles); a van Gogh of a prison courtyard (including a self-portrait), expressing his feelings about being stuck in an psychiatric clinic

- A Gaugin still life of three colorful dead parrots, a tropical flower (musa?), and a canteen on a table; really interesting; a typical composition for a European still live but with tropical materials!

- Several Matisses from his more figureative period; a whole room of Matisse, some of them getting more abstract. Two of Matisse's palettes, displayed as art (his daughter apprently delivered them personally). Matisse table-top bronze of a jaguar that has caught a hare.

- A few Rousseaus; a room of picassos.

- Fernand Leger; some really abstract stuff; cubism and multicolored abstracts

- A small bronze object labeled "Man seen by a flower"; you can google an image of it. It's an attractive object, but I couldn't make head or tail of the title.

- Some Chagalls.

- Among the 20th-century things, I liked two by Ernst Nichel, Woman in a Slip and Unemployment Line

- A piece by Armand Fernandez: an exploded violin (actually parts of two) made of real wood and metal, sort of a three-dimensional cubist view (much better than painted cubist versions)

- Some Rockwell Kent, subjects in Greenland

A very worthwhile museum, even if that's only half of it!

Both Rachel and the couple she went off with made successful rendezvous with the groups they were supposed to join, and they all made it back to the ship for dinner. According to Google, the walk from the Tretyakov to the Pushkin should have been about half an hour, but of course they got lost and had to ask for directions several times, so it took them an hour, but they got there and saw what they'd come to see.

Both Rachel and the couple she went off with made successful rendezvous with the groups they were supposed to join, and they all made it back to the ship for dinner. According to Google, the walk from the Tretyakov to the Pushkin should have been about half an hour, but of course they got lost and had to ask for directions several times, so it took them an hour, but they got there and saw what they'd come to see.

At dinner, somebody (David?) had the avocado, fennel, and green apple salad with smoked salmon (they must buy their smoked salmon by the carload; we ate pounds of it for breakfast every morning).

Someone else (Rachel?) orderd the forest-mushroom risotto with shaved Parmesan.

Nobody chose the cream of spinach soup.

Ev, as usual, had the cheese plate—Tilsiter and Goat Cheese on this occasion; we had to ask which was which—with plum chili chutney.

Ev, as usual, had the cheese plate—Tilsiter and Goat Cheese on this occasion; we had to ask which was which—with plum chili chutney.

I, on the other hand, had to order the Russian specialty: Siliotka Pod Shuboj (layered salad with herring, beets, potatoes, carrots, and sour cream). And it was yummy. It had been assembled (and was served) in a small mason jar (probably designed for baking pâtés in). It came garnished with half a cherry tomato, a wedge of boiled egg, a tiny romaine leaf, a sprig of parsley, and what I think was a tiny, slender heart of palm.

For the main course, we all chose the Russian specialty, chicken Kiev. (The other choices were Norwegian style halibut and wok-fried chinese egg noodles with shiitakes and veggies.). And we were all pretty underwhelmed. The chicken breast was dry and overcooked (except in one spot in mine where it was raw), and the butter filling wasn't enough to make up for it. Mine had retained more filling than some, because some of the packets had leaked in the fryer and lost some melted butter.

For the main course, we all chose the Russian specialty, chicken Kiev. (The other choices were Norwegian style halibut and wok-fried chinese egg noodles with shiitakes and veggies.). And we were all pretty underwhelmed. The chicken breast was dry and overcooked (except in one spot in mine where it was raw), and the butter filling wasn't enough to make up for it. Mine had retained more filling than some, because some of the packets had leaked in the fryer and lost some melted butter.

Dessert was good though. Somebody had the chocolate cherry cake.

Then it was back to the buses yet again for our "Moscow by Night" tour. On the ride back into town, our guide told us:

- If you drive 40 minutes after drinking one beer and the police test you, you get a $1000 fine and lose your driver's license for 18 months.

- Casinos are illegal except in four resorts in the south (Black Sea region). Casinos used to be everywhere, but they were banned about te year 2000. The proposal to put just a few in Siberia didn't go over well, so the authorities settled on the Black Sea resorts instead.

- Betting on horse races and sports is legal.

- The luminous red stars on the tops of the Stalin highrises are 5000-w light bulbs inside ruby-colored glass.

- No earthquakes here, because Moscow sits on bedrock that consists of a very thick solid granite platform.

Our first stop was the top of the Sparrows Hills, which provides a wide view over Moscow. Here, David, Ev, and Rachel pose in front of the railing with Moscow illuminated behind them. Just out of the frame to the right is the top of a "junior ski jump" for use in the winter. Note that we're all wired for sound. On every tour, we brought along our "Quietvox" listening devices, which permitted our guides to speak directly into our ears in a conversational tone rather than shouting over the background noise and the shouts of other tour guides.

Our first stop was the top of the Sparrows Hills, which provides a wide view over Moscow. Here, David, Ev, and Rachel pose in front of the railing with Moscow illuminated behind them. Just out of the frame to the right is the top of a "junior ski jump" for use in the winter. Note that we're all wired for sound. On every tour, we brought along our "Quietvox" listening devices, which permitted our guides to speak directly into our ears in a conversational tone rather than shouting over the background noise and the shouts of other tour guides.

Here and at many other locations, wherever Russian tourists gathered, we found street vendors selling food, and the most popular item was corn on the cob, on a stick. It seems Khruschev discovered corn on the cob when he visited the U.S. and popularized the idea in Russia, where it persists to this day.

The right-hand photo shows one of Stalin's high-rises. It's now the seat of the Moscow Universty; you face if you turn your back to the overlook.

The large parking lot at Sparrows Hills is the nocturnal gathering place of hundreds of motorcycles, whose riders exchange notes, admire each other's paint jobs and accessories, etc. It's also a popular venue for street drag racing, although that's not really legal. We even saw a convertible drive by in which, as promised, a bunch of drunken blue-bereted paratroopers were standing up and singing at 30 mph.

Next stop was Red Square (now reopened after the paratroopers' festivities). At the right, you can see the illuminated facade of GUM.

Next stop was Red Square (now reopened after the paratroopers' festivities). At the right, you can see the illuminated facade of GUM.

The statue at the right is of Minin and Pozharsky, who organized the successful defense of Russia against the Polish invasion in the 17th century. That invasion took the form of an attempt to install on the Russian throne a "False Dmitri"—i.e., a Polish buy claiming to be the unfortunate little son of Ivan the Terrible who was probably killed by Boris Gudonov. After they got rid of him, they organized the election of the first Romanov.

The statue used to stand in the middle of Red Square, but once Lenin's tomb was installed, it gave the impression of one guy handing a sword to another guy and pointing at the tomb, so they moved it to a position right in front of St. Basil's.

Also in Red Square, the guide pointed out a little bittie tower perched on the Kremlin wall near the Saviour tower. It's the "Tsar's tower"; Ivan the Terrible used to like to sit there (back when it was just a wooden structure), overlooking the square.

On the bus part of the tour we passed the Dr. Zhivago restaurant, considered the best in the city; the children's department store (Rachel was practically drooling); and the KGB building (four stories tall, but said to be the tallest in the country because, from its windows, you could see Siberia).

Half-way through the tour, we arrived back at the romantic-padlock bridge. The photo at the right is the flower-covered heart, illuminated for the evening. (The flowers and ivy are artificial.) There we left the buses and walked over the bridge to board a tour boat. The right-hand photo shows a couple of the mesh trees covered with padlocks. I'm sure city planners the world over would like to smack that first couple who had the bright idea to engrave a padlock and attach it to a bridge in Paris. The practice has spread like a plague the world over.

Half-way through the tour, we arrived back at the romantic-padlock bridge. The photo at the right is the flower-covered heart, illuminated for the evening. (The flowers and ivy are artificial.) There we left the buses and walked over the bridge to board a tour boat. The right-hand photo shows a couple of the mesh trees covered with padlocks. I'm sure city planners the world over would like to smack that first couple who had the bright idea to engrave a padlock and attach it to a bridge in Paris. The practice has spread like a plague the world over.

At the left is a photo of a monument we've driven by several times. It's a ship in full sail, with Peter the Great standing in the prow, balanced on top of a column out of which protrude the prows of other ships (those of defeated enemies, presumably). And it's big, 98 meters tall! Apparently Muscovites consider it horribly ugly and are lobbying to have it removed.

At the left is a photo of a monument we've driven by several times. It's a ship in full sail, with Peter the Great standing in the prow, balanced on top of a column out of which protrude the prows of other ships (those of defeated enemies, presumably). And it's big, 98 meters tall! Apparently Muscovites consider it horribly ugly and are lobbying to have it removed.

At the right is the cathedral of Christ the Savior, which we toured the following day.

Other sights included the original Red October chocolate factory (illuminated in red, of course), the illuminated Kremlin walls, illuminated bridges, a monastery, and Russia's first orphanage, built by one of the Catherines.

As we pulled back into the boat's berth, by the padlock bridge, a few raindrops started to fall. We piled off the boats and scurried back across the bridge (carefully, as the granite paving was very slippery) and reboarded the waiting buses. I'd have made it pretty much dry except that the guy ahead of me couldn't get his umbrella closed and jammed it in the bus door. Still we didn't get worse than damp, and that was the worst weather of the trip; it lasted about 5 minutes.

By the time we got back to the ship, the rain had subsided, so the racks of red Viking umbrellas waiting for us as we left the bus weren't needed. Each ship apparently carries a couple of hundred umbrellas, and whenever rain threatens, you can take one with you on tours. They set them out on specially designed wooden racks by the gangway.

Then it was off to bed and to recharge our Quietvoxes for the following day's 8:30 a.m. tour.

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

But to begin at the beginning. I paused before going out to breakfast to photograph this handy little reading light above my bed, with my hand in the shot for scale. Flush with the headboard, it was turned off, but if you used a finger to push on the little round recess below the light, it rotated out of its socket, lit up, and could be swiveled to the desired angle. It was equipped with very bright LED elements. To turn it off, you just pushed it back into position, flush with the headboard.

But to begin at the beginning. I paused before going out to breakfast to photograph this handy little reading light above my bed, with my hand in the shot for scale. Flush with the headboard, it was turned off, but if you used a finger to push on the little round recess below the light, it rotated out of its socket, lit up, and could be swiveled to the desired angle. It was equipped with very bright LED elements. To turn it off, you just pushed it back into position, flush with the headboard.

Then it was off to the buses for the trek back into central Moscow. At the left here, David and Rachel pose by the bow of our ship. The Cyrillic lettering over their heads transliterates as "Viking Akun."

Then it was off to the buses for the trek back into central Moscow. At the left here, David and Rachel pose by the bow of our ship. The Cyrillic lettering over their heads transliterates as "Viking Akun."

As I mentioned when I described Red Square, the first wall of the Kremlin, which borders the square, continues past St. Basil's; you can see it to the left of the cathedral. In the shot to the right, you see it reach the southeast corner. The tallest onion dome behind it is the Delphian tower, where the Tsar bell was to have hung (the bell now rests near its foot).

As I mentioned when I described Red Square, the first wall of the Kremlin, which borders the square, continues past St. Basil's; you can see it to the left of the cathedral. In the shot to the right, you see it reach the southeast corner. The tallest onion dome behind it is the Delphian tower, where the Tsar bell was to have hung (the bell now rests near its foot).

Once portraiture got going, it flourished. At the left here is a very famous portrait of Alexander Pushkin painted by O. A. Kiprensky. We were repeatedly assured that Pushkin is to Russian poetry and literature what Shakespeare is to English poetry and literature.

Once portraiture got going, it flourished. At the left here is a very famous portrait of Alexander Pushkin painted by O. A. Kiprensky. We were repeatedly assured that Pushkin is to Russian poetry and literature what Shakespeare is to English poetry and literature.

After a school of "realists" emerged, yet another group, called "critical realists" showed up. Their paintings, besides being realistic, were intended as social criticism. In the example at the left, by V. G. Perov, three children struggle to haul a barrel of water. The boy who modeled for the central figure died shortly thereafter, and his mother came to the artist to try to buy the painting, the only image of her son, but it had already been sold to a private collector (presumably Tretyakov).

After a school of "realists" emerged, yet another group, called "critical realists" showed up. Their paintings, besides being realistic, were intended as social criticism. In the example at the left, by V. G. Perov, three children struggle to haul a barrel of water. The boy who modeled for the central figure died shortly thereafter, and his mother came to the artist to try to buy the painting, the only image of her son, but it had already been sold to a private collector (presumably Tretyakov).

On our way through the museum, we passed through innumerable schools of art, including a room full of the "orientalism" we've seen elsewhere, when Europe became fascinated by Egypt and the world beyond Suez.

On our way through the museum, we passed through innumerable schools of art, including a room full of the "orientalism" we've seen elsewhere, when Europe became fascinated by Egypt and the world beyond Suez.

The rest of us got back on the bus and headed for lunch. On the way, we passed this bridge, which is the designated location in Moscow for the attachment of romantic padlocks. The big flowered heart (with the inevitable tourist posing in front of it in a bright green shirt) marks the entrance to the bridge. Just above her head and just below the point at the top of the heart, you can see a blurry, christmas-tree like object, which is a metal mesh tree covered with red-beribboned romantic padlocks. The bridge bears several of these metal trees.

The rest of us got back on the bus and headed for lunch. On the way, we passed this bridge, which is the designated location in Moscow for the attachment of romantic padlocks. The big flowered heart (with the inevitable tourist posing in front of it in a bright green shirt) marks the entrance to the bridge. Just above her head and just below the point at the top of the heart, you can see a blurry, christmas-tree like object, which is a metal mesh tree covered with red-beribboned romantic padlocks. The bridge bears several of these metal trees.

On this ride, and on many others, we passed this underground shopping mall. It is lit by a whole collection of domed skylights, of which this is the largest. I tried several times to get a better photo of it, but the bus just wasn't quite high enough. What's special about this dome is that it functions as a clock, rotating slowly throughout the day. It's decorated with half of a map of the world, so that you can see what time it is in different cities, and the ocean areas are decorated with constellations of stars. That's the State Museum and a tower of the Kremlin wall behind it.

On this ride, and on many others, we passed this underground shopping mall. It is lit by a whole collection of domed skylights, of which this is the largest. I tried several times to get a better photo of it, but the bus just wasn't quite high enough. What's special about this dome is that it functions as a clock, rotating slowly throughout the day. It's decorated with half of a map of the world, so that you can see what time it is in different cities, and the ocean areas are decorated with constellations of stars. That's the State Museum and a tower of the Kremlin wall behind it.

David and I both chose the pork steak with BBQ sauce, country potatoes, and green beans wrapped in bacon.

David and I both chose the pork steak with BBQ sauce, country potatoes, and green beans wrapped in bacon.

Surprisingly, only four other people were on the bus to the Pushkin. We met the two others there (the ones who had gone directly, with Rachel). Impressionists are usually a big draw, so I expected more. For the record, the museum has nothing whatever to do with Pushkin the poet; Russians just like naming things after him.

Surprisingly, only four other people were on the bus to the Pushkin. We met the two others there (the ones who had gone directly, with Rachel). Impressionists are usually a big draw, so I expected more. For the record, the museum has nothing whatever to do with Pushkin the poet; Russians just like naming things after him. A room of Renoirs; his famous portrait of Jeanne Samary in a green dress, head and shoulders only (the full-length view is at the Hermitage). Very colorful and with a colorful background instead of dark. In the Garden under the Trees of the Moulin de la Galette (woman in a striped dress with a blue sash). David took a few photos, which I use two of here, but he didn't photograph the labels, so I can't confidently attribute the others.

A room of Renoirs; his famous portrait of Jeanne Samary in a green dress, head and shoulders only (the full-length view is at the Hermitage). Very colorful and with a colorful background instead of dark. In the Garden under the Trees of the Moulin de la Galette (woman in a striped dress with a blue sash). David took a few photos, which I use two of here, but he didn't photograph the labels, so I can't confidently attribute the others.

A room of mostly Cezanne; Pierrot and Harlequin; a plate of apples and some pears on a dishcloth.

A room of mostly Cezanne; Pierrot and Harlequin; a plate of apples and some pears on a dishcloth.

Both Rachel and the couple she went off with made successful rendezvous with the groups they were supposed to join, and they all made it back to the ship for dinner. According to Google, the walk from the Tretyakov to the Pushkin should have been about half an hour, but of course they got lost and had to ask for directions several times, so it took them an hour, but they got there and saw what they'd come to see.

Both Rachel and the couple she went off with made successful rendezvous with the groups they were supposed to join, and they all made it back to the ship for dinner. According to Google, the walk from the Tretyakov to the Pushkin should have been about half an hour, but of course they got lost and had to ask for directions several times, so it took them an hour, but they got there and saw what they'd come to see.

Ev, as usual, had the cheese plate—Tilsiter and Goat Cheese on this occasion; we had to ask which was which—with plum chili chutney.

Ev, as usual, had the cheese plate—Tilsiter and Goat Cheese on this occasion; we had to ask which was which—with plum chili chutney.

For the main course, we all chose the Russian specialty, chicken Kiev. (The other choices were Norwegian style halibut and wok-fried chinese egg noodles with shiitakes and veggies.). And we were all pretty underwhelmed. The chicken breast was dry and overcooked (except in one spot in mine where it was raw), and the butter filling wasn't enough to make up for it. Mine had retained more filling than some, because some of the packets had leaked in the fryer and lost some melted butter.

For the main course, we all chose the Russian specialty, chicken Kiev. (The other choices were Norwegian style halibut and wok-fried chinese egg noodles with shiitakes and veggies.). And we were all pretty underwhelmed. The chicken breast was dry and overcooked (except in one spot in mine where it was raw), and the butter filling wasn't enough to make up for it. Mine had retained more filling than some, because some of the packets had leaked in the fryer and lost some melted butter.

Our first stop was the top of the Sparrows Hills, which provides a wide view over Moscow. Here, David, Ev, and Rachel pose in front of the railing with Moscow illuminated behind them. Just out of the frame to the right is the top of a "junior ski jump" for use in the winter. Note that we're all wired for sound. On every tour, we brought along our "Quietvox" listening devices, which permitted our guides to speak directly into our ears in a conversational tone rather than shouting over the background noise and the shouts of other tour guides.

Our first stop was the top of the Sparrows Hills, which provides a wide view over Moscow. Here, David, Ev, and Rachel pose in front of the railing with Moscow illuminated behind them. Just out of the frame to the right is the top of a "junior ski jump" for use in the winter. Note that we're all wired for sound. On every tour, we brought along our "Quietvox" listening devices, which permitted our guides to speak directly into our ears in a conversational tone rather than shouting over the background noise and the shouts of other tour guides.

Next stop was Red Square (now reopened after the paratroopers' festivities). At the right, you can see the illuminated facade of GUM.

Next stop was Red Square (now reopened after the paratroopers' festivities). At the right, you can see the illuminated facade of GUM.

Half-way through the tour, we arrived back at the romantic-padlock bridge. The photo at the right is the flower-covered heart, illuminated for the evening. (The flowers and ivy are artificial.) There we left the buses and walked over the bridge to board a tour boat. The right-hand photo shows a couple of the mesh trees covered with padlocks. I'm sure city planners the world over would like to smack that first couple who had the bright idea to engrave a padlock and attach it to a bridge in Paris. The practice has spread like a plague the world over.

Half-way through the tour, we arrived back at the romantic-padlock bridge. The photo at the right is the flower-covered heart, illuminated for the evening. (The flowers and ivy are artificial.) There we left the buses and walked over the bridge to board a tour boat. The right-hand photo shows a couple of the mesh trees covered with padlocks. I'm sure city planners the world over would like to smack that first couple who had the bright idea to engrave a padlock and attach it to a bridge in Paris. The practice has spread like a plague the world over.

At the left is a photo of a monument we've driven by several times. It's a ship in full sail, with Peter the Great standing in the prow, balanced on top of a column out of which protrude the prows of other ships (those of defeated enemies, presumably). And it's big, 98 meters tall! Apparently Muscovites consider it horribly ugly and are lobbying to have it removed.

At the left is a photo of a monument we've driven by several times. It's a ship in full sail, with Peter the Great standing in the prow, balanced on top of a column out of which protrude the prows of other ships (those of defeated enemies, presumably). And it's big, 98 meters tall! Apparently Muscovites consider it horribly ugly and are lobbying to have it removed.