Monday, 7 August, Kizhi and the museum of architecture

Written 7 September 2017

It was windy in the morning; the wind was snatching spray off the whitecaps, and the ship was actually rolling noticeably at breakfast time. We were cruising at a rapid clip northward across Lake Onega toward Kizhi Island.

A large peninsula juts southward from the north coast of the lake and ends in a dense archipelago of islands. Kizhi is one of those. We stayed fairly near the edge of the lake for a while, and on the banks we could see evidence of a still-active timber industry. The logs shown here at the left look large enough to be saw timber (and I saw a few piles of planks), but we also saw many stacks of smaller stems, probably destined for paper, particle board, or some such. They all looked like pine.

A large peninsula juts southward from the north coast of the lake and ends in a dense archipelago of islands. Kizhi is one of those. We stayed fairly near the edge of the lake for a while, and on the banks we could see evidence of a still-active timber industry. The logs shown here at the left look large enough to be saw timber (and I saw a few piles of planks), but we also saw many stacks of smaller stems, probably destined for paper, particle board, or some such. They all looked like pine.

The cranes probably serve to load and unload barges.

At 9 and 10 a.m., tour escort Alexei spoke on "Trading Places: Putin and Medvedev" in the Sky Bar, but I skipped it (transcribing notes for this diary for all I was worth). At 11 a.m., though, I was on the spot for the wheelhouse tour (I missed the one in Portugal and was anxious not to lose out again!).

The left-hand photo here shows our captain standing in front of the ship's "dashboard." Tour escort Sasha stood by to translate.

The little wheel in the right-hand photo is the actual helm. It's so small!

All the controls were duplicated at the extreme right and left ends of the dashboard, for the convenience of the officer, e.g., sidling the ship up to a dock, so that he can keep visual contact with the target.

As we had already heard, the ship was built in East Germany. It entered service as the Marshall Koshovoy, but was rechristened by Viking in 2014. The ship is 129 m long by 16 m wide and draws 3 m of depth. It's 25 m tall and displaces 3.5 thousand tons (or tonnes?). The top speed is 25 km/hr (23 knots) and default cruising speed is 18.8 knots. We were currently doing 23 km/hr. Here in the middle of the lake, the ship was on autopilot; during tricky spots and locks, someone would be manning the helm. Two officers are on duty on the bridge at all times (during our tour, the second one was mostly hiding out in the little map locker behind the wheelhouse.

Here, at the left, are the levers that control the speeds of the three 1000-horse power diesel engines. They are GM-70's, which the crew insist never break down.

Here, at the left, are the levers that control the speeds of the three 1000-horse power diesel engines. They are GM-70's, which the crew insist never break down.

The ship also has a maneuverable bow thruster and is controlled by five rudders. Each engine directly drives a propeller. More recent ships built in the Czech republic have a clutch and gear box, so they can reverse without stopping the engines.

The captain commands 27 officers and crew; the ship's total staff is 99.

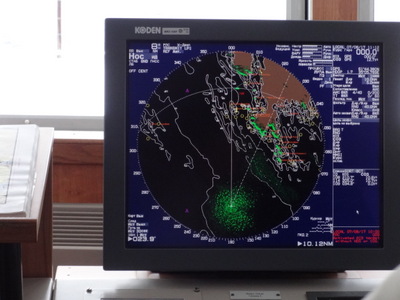

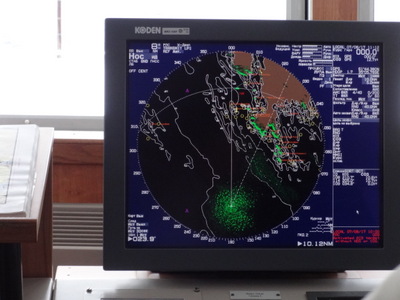

The navigational aids were myriad. The screen shown here at the right no doubt made more sense to the captain than to me.

Here's another electronic screen, this one more obviously chartlike. In addition, I could see a huge book of real paper charts, of both the lake and the rivers.

Here's another electronic screen, this one more obviously chartlike. In addition, I could see a huge book of real paper charts, of both the lake and the rivers.

I think this gauge on the ceiling is wind speed and direction (driven by instruments on the wheelhouse roof). In the center of the dashboard was a traditional binacle with an old-fashioned compass in it. on a nearby counter was a small instrument that detected ID signals and whose screen displayed the names and locations of all other nearby vessels.

One passenger asked about fuel. The ship carries 200 tons, although 120 are usually enough for the round trip. They fill up at Viking's home base in St. Petersburg, then on the way back, they top up in Yaroslavl, so they always have plenty on board.

Finally, in an upper corner of the wheelhouse, just below the ceiling, hung this icon depicting Mary and a variety of saints.

Next up was lunch, and while we were eating it, this hydrofoil overtook us. The tour guides told us the service is called the "Comet." It serves Kizhi and other islands in the cluster with several hydrofoils. The boats run at about 25 knots and are based in Petrosovotsk (spelling?) across the lake.

The lunch-time buffet included "classic meatballs" in smoked tomato sauce (pretty good) and "Russian egg," essentially a stuffed egg garnished with salmon carviar.

The lunch-time buffet included "classic meatballs" in smoked tomato sauce (pretty good) and "Russian egg," essentially a stuffed egg garnished with salmon carviar.

For his main course, David ordered the "Beef Burgundy" (i.e., boeuf bourgignon), which came with red cabbage, mixed vegetables, a bread dumpling, and a wedge of stewed apple. I don't even remember what I ordered. Neither cream of celery soup, nor chicken cheddar quesadilla, nor cavatappi Gorgonzola appealed to me. Maybe I just went back for more salad and meatballs. Ev and Rachel apparently also ordered something not photoworthy.

David had chocolate brownie with strawberry confit for dessert.

I did not come all the way to Russia to eat brownies, so I had the peach melba ice cream coupe—vanilla ice cream topped with sliced peaches and raspberry sauce.

I did not come all the way to Russia to eat brownies, so I had the peach melba ice cream coupe—vanilla ice cream topped with sliced peaches and raspberry sauce.

About the end of lunch, we pulled into Kizhi Island and got our first sight of the Church of the Transfiguration, dating from 1718 and designed by Peter the Great himself. It has 22 domes! Part of it was under repair, but even the scaffolding looked like period construction.

No buses (in fact, no motor vehicles at all) on Kizhi (or so we were told, though I saw one quite modern-looking tour bus go by in the distance). The whole island is an open-air museum of architecture and rural life. I think the Church of the Transfiguration was actually built here, the settlement it served had gone extinct. Most (perhaps all) of the other buildings have been moved here from other locations, to serve of examples of their type, and more are still being added.

At the previous evenings briefing on Kizhi, Margo made a point of saying, "If you keep to the gravel paths, you should be fine, but I have been told that I should warn you that there are snakes on the island." Snakes? I love snakes! What kind, I asked. She had no idea. Are they venomous? She didn't know. Are there no snakes elsewhere in the region, that you should mention them particularly here? No, they have snakes throughout Russia, they just told me to mention it here. Puzzling. So that evening, I Googled "kizhi island snakes," and sure enough, the place is notorious. The snakes there are the common viper, and yes, they are venomous, but they're small and not agressive. They eat frogs. The average incidence of common vipers in other areas of Russia where they occur is 1.6 per hectare. On Kizhi, it's 20 per hectare! It seems the habitat there is absolutely ideal for them; food, in the form of small frogs, abounds; and most important, they have no ready way of dispersing off the island.

"Okay," I announced, as we set off on our morning's walking tour, "I'm looking for snakes." "Just stick with me," Rachel said, with a shudder. "Wherever I am, they'll find me . . ."

We were now in Karelia region; where the language is similar to Finnish (i.e., of the Finno-Ugric family).

The church of the transfiguration is the summer church. The smaller winter church (used from October to May), Church of the Intercession, and the octagonal bell tower were built later. A stone and log wall enclose the church grounds; the wood for the wall and for the construction came from the mainland; it was dragged over the ice during the months of February and March.

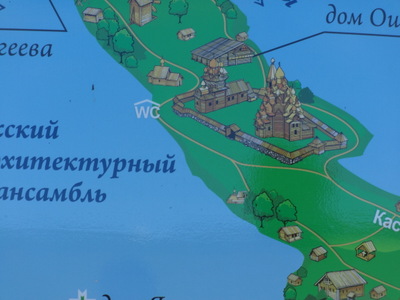

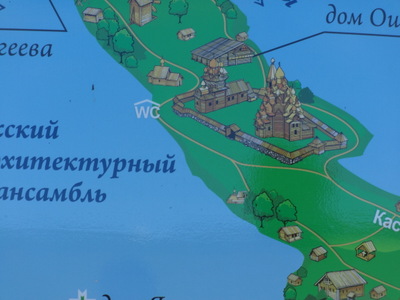

Here are a map of the island and a closer view of the section with the main church. I think the red, green, and yellow crosses indicate the region from which each building was moved.

Here are a map of the island and a closer view of the section with the main church. I think the red, green, and yellow crosses indicate the region from which each building was moved.

The ship and the hydrofoils docked on the southern side of the northwest end. We walked most of the length of the island and back on our tour.

Unlike the reservoirs we have cruised over, this lake is natural and not manmade.

The people here grew winter rye, oats, and barley; the island is too far north for wheat. Besides a demonstration field of grain, the museum maintains this demonstration garden, where I can see cabbage, onions, leeks, turnips (I think), beets, and carrots.

The people here grew winter rye, oats, and barley; the island is too far north for wheat. Besides a demonstration field of grain, the museum maintains this demonstration garden, where I can see cabbage, onions, leeks, turnips (I think), beets, and carrots.

We didn't go into the house shown at the right because it was already full of tour groups, but this shot illustrates several features of typical houses of the period (19th or early 20th century). The livestock lived in the bottom part, so the main entrance for people was up the ramp into the second floor, and the sort of gallery or balcony that ran around each floor facilitated the many repairs to the outside of the house that the harsh climate necessitated. These windows were always glass; mica windows were seldom that big, and more primitive windows would have been smaller, with wooden shutters. Glass use started here in the 15th century. The windows were even double glazed, in the sense that outer glass storm windows were added in the wintertime. Twenty people are known to have lived in this house, together with their livestock.

This is a banya (a bath house/sauna), located, as was typical, at the water's edge for convenience of jumping off the little dock into the ice-cold lake. It's the same one you can see in the background in the photo of the garden. It's early 20th century, was moved from the village of Mizhostrov, Medvezhegorsk district, Karelia, and is made of pine. This museum differed from most we visited in labeling everything in German and French, as well as Russian and English. The place has a great website; they're clearly trying to attract tourism from way beyond Russia.

This is a banya (a bath house/sauna), located, as was typical, at the water's edge for convenience of jumping off the little dock into the ice-cold lake. It's the same one you can see in the background in the photo of the garden. It's early 20th century, was moved from the village of Mizhostrov, Medvezhegorsk district, Karelia, and is made of pine. This museum differed from most we visited in labeling everything in German and French, as well as Russian and English. The place has a great website; they're clearly trying to attract tourism from way beyond Russia.

The photo at the right shows its entrance, small to help retain the heat and steam and again conveniently located by the dock.

On our way to the house that we did tour, we passed a spot where young men were restoring one of the smaller domes that had been removed from the church for the purpose. In the left-hand photo you can see the dome's inner structure and some of the aspen shingles they were hand carving to cover it with. The shingles must be replaced every 30–40 years. We were told you could buy a shingle as a souvenir, and I planned to do so before we reboarded the ship, but we walked back by a different way, and I never got another chance.

On our way to the house that we did tour, we passed a spot where young men were restoring one of the smaller domes that had been removed from the church for the purpose. In the left-hand photo you can see the dome's inner structure and some of the aspen shingles they were hand carving to cover it with. The shingles must be replaced every 30–40 years. We were told you could buy a shingle as a souvenir, and I planned to do so before we reboarded the ship, but we walked back by a different way, and I never got another chance.

Each shingle is carved flat, then soaked until it can be bent to fit the curvature of the dome. Apparently, once they're dried in the curved state, the stay that way permanently. At the right, one of our group takes a closer look at the dome.

The carvers were sitting under a tree that I had seen a couple of other places that I couldn't identify. When I next caught up with the guide, I asked her what kind of tree the shingle-makers were sitting under. She didn't know the English name but said that in Russian it was called an "iva." (Back on the ship, I asked tour escort Alexei whether he knew the English for "iva"; he didn't, but he said the French was "saule pleureur." Drat, another dead end. The tree was definitely not a weeping willow. I have a photo of the foliage, if anyone cares to have a look. It sort of says "persimmon" or even "apple" to me, but the habit was completely wrong for either of those.)

Still on the way, the guide pointed out this characteristic style of fence, constructed of trees too small to be useful for lumber or other building uses. Behind the fence in the left-hand photo, you can see the demonstration field of grain. We were there on 7 August, which, coincidentally, is the traditional day to begin the grain harvest. They hadn't started yet, but we were told that in this cimate, you don't leave the sheaves in the field to dry. You take them to a drying rack, then to the small threshing barn.

Still on the way, the guide pointed out this characteristic style of fence, constructed of trees too small to be useful for lumber or other building uses. Behind the fence in the left-hand photo, you can see the demonstration field of grain. We were there on 7 August, which, coincidentally, is the traditional day to begin the grain harvest. They hadn't started yet, but we were told that in this cimate, you don't leave the sheaves in the field to dry. You take them to a drying rack, then to the small threshing barn.

Like an American rail fence, it's held together without hardware—the verticals are lashed together with strips of bark, which the diagonals then rest on—and if a rail rots or gets otherwise damaged or broken, you can be slide it out and replace it without unfastening anything or disturbing to the rest of the structure, which you can't do with a rail fence. I think the verticals just rest on the ground, and the occasional side braces keep the whole thing from tipping over.

As we were walking around, the island's bell ringer climbed into the tower and gave a recital. The bells were (and still are today) played on a primitive "keyboard" of short sticks of wood. Each stick is hinged to a horizontal piece in front of the player, extending away from him, and the other end is attached by a cord to the clapper of a bell. The player rings the bells by beating on the sticks with his hands or fists.

Here, at last, is the interior of the house we did visit, which was slightly smaller than the one we by-passed. The front half was for the people, the back lower half for livestock. This is the main room. The orange thing hanging in the center is a cradle, suspended from the ceiling and tented with fabric. Behind it, in a white shirt and kerchief, sits a reenactor weaving ribbon—not decorative ribbon but the sort of thing that would be used for snow-shoe bindings, fish nets, etc. She also had a full-width loom for weaving fabric, presumably linen but perhaps wool. Behind her is a spinning wheel, but the guide said that most spinning was done with hand spindles—the locals distrusted that newfangled spinning-wheel technology. I can only think of one use for the four-legged stool with a round hole in the seat; I assume a chamberpot went under it.

Here, at last, is the interior of the house we did visit, which was slightly smaller than the one we by-passed. The front half was for the people, the back lower half for livestock. This is the main room. The orange thing hanging in the center is a cradle, suspended from the ceiling and tented with fabric. Behind it, in a white shirt and kerchief, sits a reenactor weaving ribbon—not decorative ribbon but the sort of thing that would be used for snow-shoe bindings, fish nets, etc. She also had a full-width loom for weaving fabric, presumably linen but perhaps wool. Behind her is a spinning wheel, but the guide said that most spinning was done with hand spindles—the locals distrusted that newfangled spinning-wheel technology. I can only think of one use for the four-legged stool with a round hole in the seat; I assume a chamberpot went under it.

Between her and the wheel, stacked on a bench and leaning against the wall, are three objects that we saw examples of in many of the buildings. They look like a single short ski with a vertical board on the front, so that you could stand on the ski with one foot, hold the vetical board, and push yourself along with the other foot. Wish I'd thought to ask about them at the time.

At the right is one of the house's two bedrooms. The bench around the side of the room might also have been used for sleeping. Just behind the basket at the lower left is a pair of sheep shears.

At the left here is the other bedroom. Houses often had just one bed, in the main room, for the master and mistress. Everyone else slept on benches or the floor, well padded with matresses and cushions.

At the left here is the other bedroom. Houses often had just one bed, in the main room, for the master and mistress. Everyone else slept on benches or the floor, well padded with matresses and cushions.

The object on the table is not a lamp but a samovar. Every Russian house was equipped with a samovar for making tea, but in fact coffee was imported here from Finland quite early, in the 19th century. The locals had never heard of Brazil and were sure the coffee was grown in Finland. It was mixed with chicory for economy.

At the right is a small hand-operated grist mill, kept right in the house. It could be used to grind a handful of grain to meal, if not to flour.

The kitchen was equipped with this massive brick stove bearing cast-iron cookware. Note the spare samovar and the butter churn on the floor to the right of it. I didn't ask about the object to the right of the churn, but from my experience in touring old kitchens, I would take it to be a kneading trough, for the preparation of bread dough.

The kitchen was equipped with this massive brick stove bearing cast-iron cookware. Note the spare samovar and the butter churn on the floor to the right of it. I didn't ask about the object to the right of the churn, but from my experience in touring old kitchens, I would take it to be a kneading trough, for the preparation of bread dough.

To the right of that was this wall of kitchen gear—another samovar, various kettles, and some bowls and dishes. The white temperature and humidity monitor with the URB charging cord is almost certainly of later vintage.

Behind the living quarters, above the stable, was a vast loft storing a huge array of farming equipment, sleds and sleighs, small boats, fish traps, fish nets, and carpentry tools. The guide spent some time explaining one implement lying on the floor; it was carved from a single huge wooden beam and incorporated a system of slots and eyelets. She explained that it had only one use—making new runners for sleds and sleighs. Long straight strips of wood were hewn into the right length, width, and thickness and given the appropriate rounded point on one end. They were then soaked for days to make them pliable enough to bend, then set into the slot of the big beam. Ropes were run through the eyelets and cranked tight by means of levers to bend the pointed end into the shape of a runner, and the runner was then dried in place. Sleds and sleighs were the only means of transport for a large part of the year, so a good supply of smooth, efficient runners was essential.

Another implement we saw, but that I didn't get a good photo of, is what the guide called a flax masher. After flax stalks are harvested and retted (i.e., soaked for a long time in water to rot the soft parts), they are air dried and then mashed. The sturdy cellulose fibers that will become linen survive the process, but the rotted soft tissue is crushed and crumbled away. A flax masher is a long log with a deep V-shaped groove cut along its length. A corresponding long v-shaped piece of wood fits into the groove and is hinged to the log at one end. The whole thing is leaned on a saw-horse so that the hinged end is on the ground and the other end at comfortable working height. To mash the flax, you lift the v-shaped piece of wood out of the groove (it has a handle at the unhinged end for the purpose), slide a hand-held bundle dry flax stalks between it and the log, and press the v-shaped piece of wood back into the groove. You repeat the movement, shifting the bundle of flax each time, until all of it has been mashed into the v-shaped groove and the soft parts crumbled away, leaving just the linen fibers.

Beyond the house we visited and its bath house, we came to a windmill. The whole building was set on a pivot so that it could be rotated always to face the wind.

Beyond the house we visited and its bath house, we came to a windmill. The whole building was set on a pivot so that it could be rotated always to face the wind.

We also passed a small chapel. Chapels differ from churches in that they don't have altars, so they could be also be used as multiple-purpose rooms or community halls, but they couldn't be used for anything involving the sacraments, like marriages or baptisms, nor could worship services be held there.

Then, as we circled back toward the summer church, we came to the tiny, much older Church of the Lasarus Resurrection. Its explanatory panel said "XIV–XVI century?" It was moved here from the Murom Monastery located on Onega Lake (Pudozh district). Like the others, it's built of pine with an aspen dome. According to legend, it wa built by Russian monk Lazarus of Murom, founder of the monastery (1286–1391).

The close view of its entrance at the right shows how windows were constructed before glass was available. From inside the wodden shutter could be slide to one side. The great curved wooden door handle may be original. The metal padlock isn't. Nor is the conductor for the lightning rod on the dome, which you can barely see to the right of the dome in this photo. You can barely see the lightning rod itself in the long view of the church.

The wooden structure to the left of the church in the long view is a navigational aid intended for ships on the lake, part of which you can see behind the church.

Out in front of the house was a display of the sort of hand-whittled dolls and toys the locals made. Again, I suspect the jet airplane at the far left is a fairly recent addition to the repertory.

Out in front of the house was a display of the sort of hand-whittled dolls and toys the locals made. Again, I suspect the jet airplane at the far left is a fairly recent addition to the repertory.

At the right here is the icon stand in the summer church. The guide told us that the interiors of wooden churches weren't painted, so only the icon stand and some separate icons on easels are colorful.

Here, the population were "new believers. One crossed oneself with three fingers, and the bottom touch was as low as you could reach.

Early on, what little education was available came from the priest, who taught little reading and writing in the church to boys only. Around the turn of the 20th C, a few civil schools were organized, but not on the island. The school was about 20 km away on the mainland. Maybe 35 kids at a time learned basic math and basic geography. The island's population was about 150 people; maybe 1500 people occupied the whole group of islands.

Here, at the left is the church yard of the large church. The crosses mark graves, and most of them are protected by little wooden roofs, presumably intended to retard deterioration of the wooden crosses themselves.

Here, at the left is the church yard of the large church. The crosses mark graves, and most of them are protected by little wooden roofs, presumably intended to retard deterioration of the wooden crosses themselves.

The water you can see beyond the churchyard is on the far side of the island from where we approached and our ship moored; the place is not very big.

At the right here is a better view of the house we didn't visit (the one that housed 20 people, with its kitchen garden in the foreground and the church behind it.

On the island, and especially along the path from the boat landing to the buildings, many of the trees were labeled, in English, Latin, and Russian. Very helpful. I wish they had labeled the one the carvers were sitting under.

Written 8 September 2017

Among the labeled trees were a willow (Salix caprea), an elm (Ulmus laevis), an oak (Quercus robur), two birches (Betula pendula var. carelica and B. pubescens), two alders (Alnus incana and A. glutinosa), and at long last, the pine we've been seeing everywhere (Pinus sylvestris), the Scots pine.

I couldn't identify the grasses, of course, but among the little flowering herbs, I saw campanulas; small purplish thistle-like things; fireweed (rose-bay willow herb); strawberries; pink clover; Dutch white clover, cow parsley, a yarrow-like thing, ox-eye daisies, moth mullein, sorrel, horsetails, butter and eggs (a small yellow scoph), and Rubus (blackberry/dewberry/raspberry, who knows?). and of course the ubiquitous "d—n little yellow composites." Also, in the shallows at the water's edge, Lemna (duckweed). Most of these, of course, are widespread weeds; I had no way of knowing which ones might actually be native here.

Disappointingly, although I spotted a few frogs, I never saw a snake. Somebody from another group mentioned later that they had spotted one, so I guess they do exist.

Finally, here we are, lined up for display, draped with our QuietVoxes, binoculars, cameras, umbrellas, and other badges of tourism. Those are the garden and bath house far behind us at the left. We're back on "our" side of the island now. From here, we walked back to the ship, as we were due back there at 4:45 p.m. The ship was to cast off as soon as everyone was back aboard, and we were invited to a 5:00 p.m. "sail away" party on the sundeck, with champagne, snacks, and views of the island.

Finally, here we are, lined up for display, draped with our QuietVoxes, binoculars, cameras, umbrellas, and other badges of tourism. Those are the garden and bath house far behind us at the left. We're back on "our" side of the island now. From here, we walked back to the ship, as we were due back there at 4:45 p.m. The ship was to cast off as soon as everyone was back aboard, and we were invited to a 5:00 p.m. "sail away" party on the sundeck, with champagne, snacks, and views of the island.

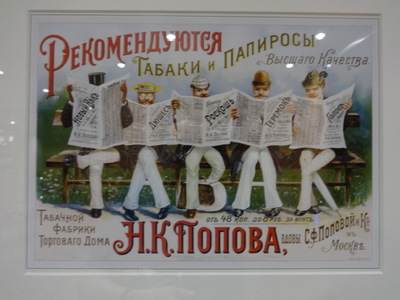

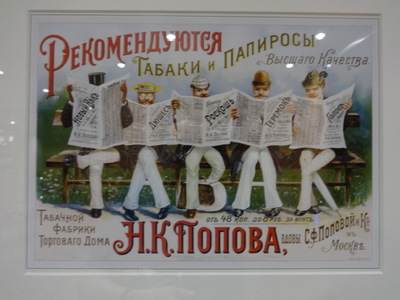

On my way to the party, I paused to photograph this wonderful old tobacco ad in its frame by the elevator. I especially like the way the artist has managed to use the mens' legs, briefcase, and umbrella to spell out "tabak." I think the wording at the top says "recommended tobacco and papers."

Another framed display we walked past daily is this directory of the ship's senior staff. Top row: Capain Vladimir Ilyin, Head of Hotel Services Karoline Landa. Second row: Program Directory Margo Goncharova, Executive Chef Leonidas Kritharas, Maitre d'Hotel Dominik Schwemmer. Bottom row: Guest Services Manager Elena Litovchenko, Housekeper Natalia Volodchenko, Chief Mechanic Stanislav Romanchuk. Gems every one.

Another framed display we walked past daily is this directory of the ship's senior staff. Top row: Capain Vladimir Ilyin, Head of Hotel Services Karoline Landa. Second row: Program Directory Margo Goncharova, Executive Chef Leonidas Kritharas, Maitre d'Hotel Dominik Schwemmer. Bottom row: Guest Services Manager Elena Litovchenko, Housekeper Natalia Volodchenko, Chief Mechanic Stanislav Romanchuk. Gems every one.

At the right is one of the items passed at the "sail-away party—grape cream tartlets. Other waiters passed savory items.

After the party, tour escort Alexei offered the second language lesson, but I skipped it, not even having mastered the material from the first. Then Margo took over to tell us about the following day's excursion before dinner.

David's starter was called "tomato-mozzarella jalousie" and came with iced cucumber-yogurt soup and basil pesto. It took the form of a stack of alternating slices of tomato and mozzarella drizzled with balsamic syrup and pesto and garnished with basil leaves and pine nuts. The soup is in the square green glass.

David's starter was called "tomato-mozzarella jalousie" and came with iced cucumber-yogurt soup and basil pesto. It took the form of a stack of alternating slices of tomato and mozzarella drizzled with balsamic syrup and pesto and garnished with basil leaves and pine nuts. The soup is in the square green glass.

I ordered the smoked butterfish (marked as a Russian specialty) with Waldorf salad and orange dressing. The Waldorf salad was mostly finely apple and mayo, with half an olive on top. At the right-hand side, you can see David's cucumber soup which he wouldn't touch, so I ate it.

In the U.S., a butterfish is a little thing the size of your hand, usually cooked whole, so I was surprised to get these large cross sections of filet from something that must be three feet long! It took me a while on the internet, but I finally tracked it down. It's what we call "escolar," Lepidocybium flavobrunneum, often called "white tuna" on sushi menus. Whenever you look it up on line now, it comes with hysterical health warnings. But it was good. Maybe the smoking was the Russian part, since it's a semitropical fish.

Rachel may have had the "cream of buttersquash soup" with whipped cream and toasted almonds. The other choice was arugula salad with cherry tomatoes and pine nuts, prosciutto, grissini bread sticks, and basil vinaigrette. Ev's cheese plate was Camembert and Emmenthal.

David's main course was roasted duck breast and duck leg confit with red thai curry sauce, wok vegetables, and basmati rice. He said it was good but not really what he expects when he orders duck.

David's main course was roasted duck breast and duck leg confit with red thai curry sauce, wok vegetables, and basmati rice. He said it was good but not really what he expects when he orders duck.

I had the "Sudak," described as seared fillet of perch with sautéed vegetable, barley, and parsley beurre blanc. I'm fond of seared fish, barley, and beurre blanc, so it was a no-brainer. I never get to eat barley at home because David hates it; he says it's like eating pussy willows. I assumed "Sudak" was either a location (it was billed as a Russian specialty) or a cooking style, but it turns out to be the species of fish—our old friend Sander lucioperca, the European pike-perch ("sandre" in French, "zander" in English).

Nobody ordered the vegetarian spring roll with sweet and sour sauce.

For dessert, the chocolate orange cake was roundly ignored. David and Ev both had the dark chocolate mousse with hazelnut crumble and fresh cherries. Rachel (who's allergic to hazelnuts) had the fresh grape sorbet, and I (who find dark chocolate mousse cloying) chose the ginger ice cream with chocolate sauce. Again, caramel sauce would be weird with ginger ice cream.

For dessert, the chocolate orange cake was roundly ignored. David and Ev both had the dark chocolate mousse with hazelnut crumble and fresh cherries. Rachel (who's allergic to hazelnuts) had the fresh grape sorbet, and I (who find dark chocolate mousse cloying) chose the ginger ice cream with chocolate sauce. Again, caramel sauce would be weird with ginger ice cream.

To entertain us in the evening, Margo had organized a movie trivia contest, and this time we talked David into joining us. The quiz consisted of four rounds. In the first, Margo briefly showed a movie poster with the title blacked out while she simultaneously played a brief clip of the theme from a different movie. We had to name both movies. On three of the five items, we got both, but on the other two we got only one. In one case, we completely blanked on the poster, and on the other, the theme clip was so short that we entirely missed it. In all five cases, the moment the theme clip ended, Sigmund started playing the endlessly annoying "thinking music" from Jeopardy, and that didn't help. For one of the themes, a military march, Ev wrote Bridge over the River Kwai, but I said, "No, that's not it! What was the name of that movie . . . ? It had John Belushi in it . . . 1941!" But then the lyrics came to me, and I was singing under my breath (". . . Fickle, oh, yes I'm fickle, but it's a dollar to a nickle, that . . .") and "No, no, it's not! It's The Great Escape!" just under the wire.

The second category showed a film clip that ended in the middle of an actor's speech, and we had to complete the line (e.g., ". . . I"ll get you my pretty, and your little dog too!" and ". . . yes, I'm serious, and don't call me shirley" and ". . . You can't handle the truth!" We nailed four out of five of those.

The third category was to take a series of song titles and to extract the right words from them to form a movie title. That was my category; we nailed all five. David and the sinnetts knew the song titles, and I was able to pull out the right words.

Fourth, we were shown a longish clip of the famous scene of Gene Kelly singing and dancing in the rain and then had to answer trivia questions about it. (How many other people appear in the clip? Three. What color were his shoes? Brown. Was he wearing a tie, a bow tie, or a scarf? A tie.) We got four out of five on that—we were fooled by the sign in the shop window advertising haircuts and said the clip ended with him in front of a barbershop, rather than a pharmacy. We figured that last goof had sunk us, but surprisingly our table took second place! The prize was a bottle of Rosée d'Anjou that David, Ev, and Rachel shared a few days later over our last dinner aboard.

Finally, still on the island before we came back to the ship, in the gift-shop area near the dock, I admired souvenir hats and muffs made of rabbit, mink, and fox fur, but the only souvenir I bought was a small, maybe one-inch square, pyramid cut from shungite, which they called "our local mineral" and is apparently 98% pure carbon.

Finally, still on the island before we came back to the ship, in the gift-shop area near the dock, I admired souvenir hats and muffs made of rabbit, mink, and fox fur, but the only souvenir I bought was a small, maybe one-inch square, pyramid cut from shungite, which they called "our local mineral" and is apparently 98% pure carbon.

I did get this photo, though, of a shop window. It's full of glare and reflections, but it shows little models of buildings on the island, including the windmill. Most importantly, though, it shows what the church looks like with all its domes in place!

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

A large peninsula juts southward from the north coast of the lake and ends in a dense archipelago of islands. Kizhi is one of those. We stayed fairly near the edge of the lake for a while, and on the banks we could see evidence of a still-active timber industry. The logs shown here at the left look large enough to be saw timber (and I saw a few piles of planks), but we also saw many stacks of smaller stems, probably destined for paper, particle board, or some such. They all looked like pine.

A large peninsula juts southward from the north coast of the lake and ends in a dense archipelago of islands. Kizhi is one of those. We stayed fairly near the edge of the lake for a while, and on the banks we could see evidence of a still-active timber industry. The logs shown here at the left look large enough to be saw timber (and I saw a few piles of planks), but we also saw many stacks of smaller stems, probably destined for paper, particle board, or some such. They all looked like pine.

Here, at the left, are the levers that control the speeds of the three 1000-horse power diesel engines. They are GM-70's, which the crew insist never break down.

Here, at the left, are the levers that control the speeds of the three 1000-horse power diesel engines. They are GM-70's, which the crew insist never break down.

Here's another electronic screen, this one more obviously chartlike. In addition, I could see a huge book of real paper charts, of both the lake and the rivers.

Here's another electronic screen, this one more obviously chartlike. In addition, I could see a huge book of real paper charts, of both the lake and the rivers.

The lunch-time buffet included "classic meatballs" in smoked tomato sauce (pretty good) and "Russian egg," essentially a stuffed egg garnished with salmon carviar.

The lunch-time buffet included "classic meatballs" in smoked tomato sauce (pretty good) and "Russian egg," essentially a stuffed egg garnished with salmon carviar.

I did not come all the way to Russia to eat brownies, so I had the peach melba ice cream coupe—vanilla ice cream topped with sliced peaches and raspberry sauce.

I did not come all the way to Russia to eat brownies, so I had the peach melba ice cream coupe—vanilla ice cream topped with sliced peaches and raspberry sauce.

Here are a map of the island and a closer view of the section with the main church. I think the red, green, and yellow crosses indicate the region from which each building was moved.

Here are a map of the island and a closer view of the section with the main church. I think the red, green, and yellow crosses indicate the region from which each building was moved.

The people here grew winter rye, oats, and barley; the island is too far north for wheat. Besides a demonstration field of grain, the museum maintains this demonstration garden, where I can see cabbage, onions, leeks, turnips (I think), beets, and carrots.

The people here grew winter rye, oats, and barley; the island is too far north for wheat. Besides a demonstration field of grain, the museum maintains this demonstration garden, where I can see cabbage, onions, leeks, turnips (I think), beets, and carrots.

This is a banya (a bath house/sauna), located, as was typical, at the water's edge for convenience of jumping off the little dock into the ice-cold lake. It's the same one you can see in the background in the photo of the garden. It's early 20th century, was moved from the village of Mizhostrov, Medvezhegorsk district, Karelia, and is made of pine. This museum differed from most we visited in labeling everything in German and French, as well as Russian and English. The place has a great website; they're clearly trying to attract tourism from way beyond Russia.

This is a banya (a bath house/sauna), located, as was typical, at the water's edge for convenience of jumping off the little dock into the ice-cold lake. It's the same one you can see in the background in the photo of the garden. It's early 20th century, was moved from the village of Mizhostrov, Medvezhegorsk district, Karelia, and is made of pine. This museum differed from most we visited in labeling everything in German and French, as well as Russian and English. The place has a great website; they're clearly trying to attract tourism from way beyond Russia.

On our way to the house that we did tour, we passed a spot where young men were restoring one of the smaller domes that had been removed from the church for the purpose. In the left-hand photo you can see the dome's inner structure and some of the aspen shingles they were hand carving to cover it with. The shingles must be replaced every 30–40 years. We were told you could buy a shingle as a souvenir, and I planned to do so before we reboarded the ship, but we walked back by a different way, and I never got another chance.

On our way to the house that we did tour, we passed a spot where young men were restoring one of the smaller domes that had been removed from the church for the purpose. In the left-hand photo you can see the dome's inner structure and some of the aspen shingles they were hand carving to cover it with. The shingles must be replaced every 30–40 years. We were told you could buy a shingle as a souvenir, and I planned to do so before we reboarded the ship, but we walked back by a different way, and I never got another chance.

Still on the way, the guide pointed out this characteristic style of fence, constructed of trees too small to be useful for lumber or other building uses. Behind the fence in the left-hand photo, you can see the demonstration field of grain. We were there on 7 August, which, coincidentally, is the traditional day to begin the grain harvest. They hadn't started yet, but we were told that in this cimate, you don't leave the sheaves in the field to dry. You take them to a drying rack, then to the small threshing barn.

Still on the way, the guide pointed out this characteristic style of fence, constructed of trees too small to be useful for lumber or other building uses. Behind the fence in the left-hand photo, you can see the demonstration field of grain. We were there on 7 August, which, coincidentally, is the traditional day to begin the grain harvest. They hadn't started yet, but we were told that in this cimate, you don't leave the sheaves in the field to dry. You take them to a drying rack, then to the small threshing barn.

Here, at last, is the interior of the house we did visit, which was slightly smaller than the one we by-passed. The front half was for the people, the back lower half for livestock. This is the main room. The orange thing hanging in the center is a cradle, suspended from the ceiling and tented with fabric. Behind it, in a white shirt and kerchief, sits a reenactor weaving ribbon—not decorative ribbon but the sort of thing that would be used for snow-shoe bindings, fish nets, etc. She also had a full-width loom for weaving fabric, presumably linen but perhaps wool. Behind her is a spinning wheel, but the guide said that most spinning was done with hand spindles—the locals distrusted that newfangled spinning-wheel technology. I can only think of one use for the four-legged stool with a round hole in the seat; I assume a chamberpot went under it.

Here, at last, is the interior of the house we did visit, which was slightly smaller than the one we by-passed. The front half was for the people, the back lower half for livestock. This is the main room. The orange thing hanging in the center is a cradle, suspended from the ceiling and tented with fabric. Behind it, in a white shirt and kerchief, sits a reenactor weaving ribbon—not decorative ribbon but the sort of thing that would be used for snow-shoe bindings, fish nets, etc. She also had a full-width loom for weaving fabric, presumably linen but perhaps wool. Behind her is a spinning wheel, but the guide said that most spinning was done with hand spindles—the locals distrusted that newfangled spinning-wheel technology. I can only think of one use for the four-legged stool with a round hole in the seat; I assume a chamberpot went under it.

At the left here is the other bedroom. Houses often had just one bed, in the main room, for the master and mistress. Everyone else slept on benches or the floor, well padded with matresses and cushions.

At the left here is the other bedroom. Houses often had just one bed, in the main room, for the master and mistress. Everyone else slept on benches or the floor, well padded with matresses and cushions.

The kitchen was equipped with this massive brick stove bearing cast-iron cookware. Note the spare samovar and the butter churn on the floor to the right of it. I didn't ask about the object to the right of the churn, but from my experience in touring old kitchens, I would take it to be a kneading trough, for the preparation of bread dough.

The kitchen was equipped with this massive brick stove bearing cast-iron cookware. Note the spare samovar and the butter churn on the floor to the right of it. I didn't ask about the object to the right of the churn, but from my experience in touring old kitchens, I would take it to be a kneading trough, for the preparation of bread dough.

Beyond the house we visited and its bath house, we came to a windmill. The whole building was set on a pivot so that it could be rotated always to face the wind.

Beyond the house we visited and its bath house, we came to a windmill. The whole building was set on a pivot so that it could be rotated always to face the wind.

Out in front of the house was a display of the sort of hand-whittled dolls and toys the locals made. Again, I suspect the jet airplane at the far left is a fairly recent addition to the repertory.

Out in front of the house was a display of the sort of hand-whittled dolls and toys the locals made. Again, I suspect the jet airplane at the far left is a fairly recent addition to the repertory.

Here, at the left is the church yard of the large church. The crosses mark graves, and most of them are protected by little wooden roofs, presumably intended to retard deterioration of the wooden crosses themselves.

Here, at the left is the church yard of the large church. The crosses mark graves, and most of them are protected by little wooden roofs, presumably intended to retard deterioration of the wooden crosses themselves.

Finally, here we are, lined up for display, draped with our QuietVoxes, binoculars, cameras, umbrellas, and other badges of tourism. Those are the garden and bath house far behind us at the left. We're back on "our" side of the island now. From here, we walked back to the ship, as we were due back there at 4:45 p.m. The ship was to cast off as soon as everyone was back aboard, and we were invited to a 5:00 p.m. "sail away" party on the sundeck, with champagne, snacks, and views of the island.

Finally, here we are, lined up for display, draped with our QuietVoxes, binoculars, cameras, umbrellas, and other badges of tourism. Those are the garden and bath house far behind us at the left. We're back on "our" side of the island now. From here, we walked back to the ship, as we were due back there at 4:45 p.m. The ship was to cast off as soon as everyone was back aboard, and we were invited to a 5:00 p.m. "sail away" party on the sundeck, with champagne, snacks, and views of the island.

Another framed display we walked past daily is this directory of the ship's senior staff. Top row: Capain Vladimir Ilyin, Head of Hotel Services Karoline Landa. Second row: Program Directory Margo Goncharova, Executive Chef Leonidas Kritharas, Maitre d'Hotel Dominik Schwemmer. Bottom row: Guest Services Manager Elena Litovchenko, Housekeper Natalia Volodchenko, Chief Mechanic Stanislav Romanchuk. Gems every one.

Another framed display we walked past daily is this directory of the ship's senior staff. Top row: Capain Vladimir Ilyin, Head of Hotel Services Karoline Landa. Second row: Program Directory Margo Goncharova, Executive Chef Leonidas Kritharas, Maitre d'Hotel Dominik Schwemmer. Bottom row: Guest Services Manager Elena Litovchenko, Housekeper Natalia Volodchenko, Chief Mechanic Stanislav Romanchuk. Gems every one.

David's starter was called "tomato-mozzarella jalousie" and came with iced cucumber-yogurt soup and basil pesto. It took the form of a stack of alternating slices of tomato and mozzarella drizzled with balsamic syrup and pesto and garnished with basil leaves and pine nuts. The soup is in the square green glass.

David's starter was called "tomato-mozzarella jalousie" and came with iced cucumber-yogurt soup and basil pesto. It took the form of a stack of alternating slices of tomato and mozzarella drizzled with balsamic syrup and pesto and garnished with basil leaves and pine nuts. The soup is in the square green glass.

David's main course was roasted duck breast and duck leg confit with red thai curry sauce, wok vegetables, and basmati rice. He said it was good but not really what he expects when he orders duck.

David's main course was roasted duck breast and duck leg confit with red thai curry sauce, wok vegetables, and basmati rice. He said it was good but not really what he expects when he orders duck.

For dessert, the chocolate orange cake was roundly ignored. David and Ev both had the dark chocolate mousse with hazelnut crumble and fresh cherries. Rachel (who's allergic to hazelnuts) had the fresh grape sorbet, and I (who find dark chocolate mousse cloying) chose the ginger ice cream with chocolate sauce. Again, caramel sauce would be weird with ginger ice cream.

For dessert, the chocolate orange cake was roundly ignored. David and Ev both had the dark chocolate mousse with hazelnut crumble and fresh cherries. Rachel (who's allergic to hazelnuts) had the fresh grape sorbet, and I (who find dark chocolate mousse cloying) chose the ginger ice cream with chocolate sauce. Again, caramel sauce would be weird with ginger ice cream. Finally, still on the island before we came back to the ship, in the gift-shop area near the dock, I admired souvenir hats and muffs made of rabbit, mink, and fox fur, but the only souvenir I bought was a small, maybe one-inch square, pyramid cut from shungite, which they called "our local mineral" and is apparently 98% pure carbon.

Finally, still on the island before we came back to the ship, in the gift-shop area near the dock, I admired souvenir hats and muffs made of rabbit, mink, and fox fur, but the only souvenir I bought was a small, maybe one-inch square, pyramid cut from shungite, which they called "our local mineral" and is apparently 98% pure carbon.