Wednesday, 9 August, St. Petersburg and the Cossacks

Written 14 September 2017

We spent Tuesday afternoon and most of that night following the Svir River to Lake Ladoga, then across the lake and out the other side on the Neva River, our final body of water. At some point during the wee hours, we docked in St. Petersburg. Here, at the left, is the view across the river from the dining room when I came to breakfast.

We spent Tuesday afternoon and most of that night following the Svir River to Lake Ladoga, then across the lake and out the other side on the Neva River, our final body of water. At some point during the wee hours, we docked in St. Petersburg. Here, at the left, is the view across the river from the dining room when I came to breakfast.

Traffic on the river was brisk. Turning to my left after taking that photo, I got this shot of a cruise ship called the Alexander Suvapov in front of a newly opened bridge— St. Petersburg's first suspension bridge.

While I ate breakfast, I got a few more shots. Here, at the left, is the Saint Petersburg in front of the same bridge.

While I ate breakfast, I got a few more shots. Here, at the left, is the Saint Petersburg in front of the same bridge.

coming the other way was our old friend the Lev Tolstoy. All the cruise ships on the rivers seem to be red and white, regardless of cruise line.

Not all the river traffic was cruise ships—here's a load of logs on its way somewhere—but a lot of it was. When it was time to catch the buses for our 8:00 a.m. tour of the Catherine Palace, we found that the Akun was moored outboard of four other ships! We had quite a trek just to reach the pier.

Not all the river traffic was cruise ships—here's a load of logs on its way somewhere—but a lot of it was. When it was time to catch the buses for our 8:00 a.m. tour of the Catherine Palace, we found that the Akun was moored outboard of four other ships! We had quite a trek just to reach the pier.

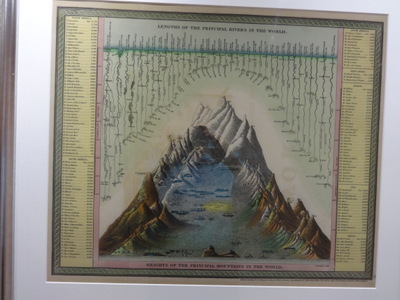

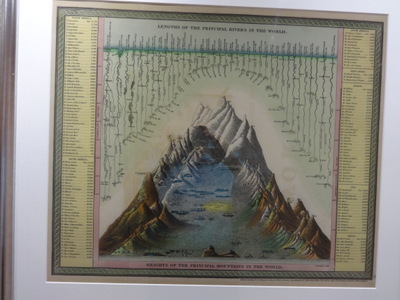

On the way, though, I stopped to snap a photo of this wonderful diagram. I don't remember which ship it was on. Across the top, it displays the relative lengths of the principal rivers of the world, from the Mississippi/Missouri and the Amazon on the left to the Yangtze and the Nile on the right, with the tiny Thames in the center. At the bottom, it displays the relative heights of the principal mountains of the world. The highest (labeled "127") is listed in the column on the right as Dwahalagiri; the diagram was prepared in 1850, six years before the mountain was named "Everest," for the first British surveyor-general of India.

Across the bottom, tiny drawings of the pyramids and of three cathedrals (St. Peter's in Rome, St. Paul's in London, and St. Patrick's in Dublin) provide scale.

As usual, on our way to Catherine Palace, which is some way out of town, we were lectured on history and culture. Part of our route was on St. Petersburg's 100-km ring road.

From 1712 to 1918, St. Petersburg was the capital city of Russia. Ivan the Terrible had lost Russia's foothold on this coast to Sweden, and Peter the Great (the boat builder, remember) wanted it back so that Russia could have a Baltic seaport. He accordingly declared war (the so-called "Northern War") on Sweden in 1700 and retook the mouth of the Neva. He built (using captured Swedish labor) a fortress there, the St. Peter and St. Paul fortress, to protect the port. He founded the city of St. Petersburg (named not for himself but for his patron saint) in 1703 and moved the capital there from Moscow in 1712 (it was only moved back after the revolution).

Within 50 years it was the largest and most important city of Russia, with a population of half a million, largely because Peter declared that it would be and forced every noble of any conseuence to have a residence there.

So that's why the region is positively littered with royal residences, about 20 of them, of which the most important are the Peterhof (the oldest), the Catherine Palace (started by and named for Peter's wife, Catherine I, and finished by his daughter Elizabeth), and the Winter Palace (downtown, now part of the Hermitage). Bartolomeo Restrelli was Elizabeth's Italian. He added vast wings to the original 20-room 1715 palace.

On our way we passed several small monuments marking perimeter of the World War II siege of St. Petersburg (then Leningrad). In other words, the palace was outside the perimeter, in enemy-held territory. It was occupied by the Germans and suffered considerable damage as a consequence. The decor of the amber room—a room entirely paneled in amber, a gift to Peter I from Frederic of Prussia and the only room where we were not allowed to take photos—was dismantled and stolen is missing to this day. It's been gradually restored, since 1970, even under the Soviets. The damage was so extensive that the palace Was only ready for visitors again in the 1960s.

The Catherine Palace (and neighboring Alexander Palace) are in the village of Pushkin. Up until the 20th century, it was called Royal Village (Tsarskoye Selo), but after the revolution that seemed incongruous, so in 1937 (the hundredth anniversary of Pushkin's birth), they changed the name.

Our "local guide" for this excursion was tour escort Alexei; Pushkin is his home town.

Our bus dropped us off near one end of the long axis of the palace, about where the red lettering is in the map at the right. We walked around to the left toward the palace and encountered this yellow-and-white building, which was the royal lycée. Pushkin was one of its first students. It was (and still is) actually connected to the palace by an enclosed elevated walkway, which you can just see to the left of the building.

Our bus dropped us off near one end of the long axis of the palace, about where the red lettering is in the map at the right. We walked around to the left toward the palace and encountered this yellow-and-white building, which was the royal lycée. Pushkin was one of its first students. It was (and still is) actually connected to the palace by an enclosed elevated walkway, which you can just see to the left of the building.

The map at the right shows the Catherine Park—the palace gardens. The palace itself and its semicircular courtyard form the half-moon-shaped gray area at the top center.

Continuing around the lycée, we first saw the palace end-on, but as we continued, more and more of it came into view, until we could see Restrelli's entire facade, which is 400 m wide.

Continuing around the lycée, we first saw the palace end-on, but as we continued, more and more of it came into view, until we could see Restrelli's entire facade, which is 400 m wide.

At the far end, jutting out at right angles to the facade, is this lacy gallery. You can see it at the left-hand end of the palace in the map. Where it meets the palace, it's on the same level, but the ground falls away to the left, so it's distal end is several meters above the ground.

We walked along the facade until we reached the midpoint, then turned away from the palace to start down the central axis of the gardens, toward the "hermitage" at what initially looks like its far end. In fact, the gardens continue as far again beyond it—Alexei said that walking the entire long axis of the gardens (from upper left to lower right on the map) takes about 45 minutes.

We walked along the facade until we reached the midpoint, then turned away from the palace to start down the central axis of the gardens, toward the "hermitage" at what initially looks like its far end. In fact, the gardens continue as far again beyond it—Alexei said that walking the entire long axis of the gardens (from upper left to lower right on the map) takes about 45 minutes.

In France, many of these walkways would be lined with plane trees (what we call sycamores), and many of the "elevated hedges" made by trimming trees into hedge-like shapes would made of the same species, but apparently plane trees don't do that well so far north, so all the hedges you see are trimmed from lime trees (what we call lindens).

During our stroll in the gardens, Rachel and I asked Alexei about his family's experience during World War II. His father was a veterinarian with the army, so he went off to war early on and wasn't heard from again for years. Alexei's mother and grandmother were evacuated from the city in a truck driven over the frozen Lake Ladoga, the only road out during the seige. The made their way to one of Russia's interior regions and spent the rest of the war there. After the war ended, his father was finally able to make his way back to join them, but he died shortly thereafter from the aftereffects of wounds he had received.

At the right is a nearer view of the "hermitage" (i.e., little royal retreat), the four-winged building about halfway between the palace and the lower right end of the gardens. On some days, you can get a guided tour that demonstrates the operation of the moving dining table. Peter the Great originated this idea (or at least first used it in a Russian palace) at the Peterhof—to avoid having servants standing around listening to the dinner conversation, you put the kitchen and service area downstairs and the dining room above it. At dinner time, a section of the dining-room floor slides aside and the fully set dining table, complete with food, rises up from below, and the guests pull up their chairs. A couple of smaller "dumbwaiter" spots on the table can be used to order more of something—the host or a guest writes the request on a slip of paper and puts it in the dumbwaiter, which sinks down into the kitchen and returns with the requested item. Slick. Alas, we weren't there on the right day or time and didn't get to see the inside of this hermitage.

From the hermitage, we walked back up the axis toward the palace and then to our left to walk along the edge of the large lake. I think the building at the left here is the one marked "grotto" on the map, right on the edge of the lake.

From the hermitage, we walked back up the axis toward the palace and then to our left to walk along the edge of the large lake. I think the building at the left here is the one marked "grotto" on the map, right on the edge of the lake.

At the right is a telephoto of a little building on the far bank, the "Turkish bath." As you can see from the map, the grounds are littered with small buildings of all sizes and shapes. All are highly decorative, and several of them (including the two nearest the right-hand end of the facade) are bathhouses.

On the lake, I spotted a great crested grebe. A little farther along, a blue tit wasv bathing in a tiny stream in a cluster of trees.

Here's an end-on view of the long lacy gallery, from the down-hill side. The gallery, designed by Scotsman Charles Cameron, we added during the reign of Cathering the Great. She lived here permanently during the late part of her life. It seems to me that they could at least have painted the souvenir shop the right shade of blue to match the palace!

Here's an end-on view of the long lacy gallery, from the down-hill side. The gallery, designed by Scotsman Charles Cameron, we added during the reign of Cathering the Great. She lived here permanently during the late part of her life. It seems to me that they could at least have painted the souvenir shop the right shade of blue to match the palace!

We then proceeded to the left around the gallery, where I was able to capture this detail confirming what Alexei had told us about the construction. Unlike the great palaces of France, which are built of stone, the ones around here are built of brick, which is then stuccoed over and painted—beautiful but really expensive to maintain, as the stucco lasts only about 15 years and must be repeatedly replaced and repainted.

In this area, we also encounted group of cats lounging on ledges and cornices of the building. We had been told that the Hermitage museum keeps a group of cats to keep rodents out of its buildings. Perhaps the Catherine Palace does as well.

We followed the side of the gallery, then the end wall of the palace, until we emerged into the parking lot that surrounds the curved side of the palace. This map shows the layout of the Alexander Palace and its grounds, adjacent to the Catherine Palace. It was commissioned by Catherine the Great for her favorite grandson, later Alexander I, and was later the favorite residence of Nicholas II, the ill-fated last Romanov tsar, and his family. Rasputin was initially buried on the grounds, but a mob soon dug him up, burned the remains, and scattered the ashes in the Neva. I think the palace is still under restoration—we didn't get to go in.

We followed the side of the gallery, then the end wall of the palace, until we emerged into the parking lot that surrounds the curved side of the palace. This map shows the layout of the Alexander Palace and its grounds, adjacent to the Catherine Palace. It was commissioned by Catherine the Great for her favorite grandson, later Alexander I, and was later the favorite residence of Nicholas II, the ill-fated last Romanov tsar, and his family. Rasputin was initially buried on the grounds, but a mob soon dug him up, burned the remains, and scattered the ashes in the Neva. I think the palace is still under restoration—we didn't get to go in.

The red "you are here" dot on the map marks both the location of the map itself and the spot where I turned around, putting my back to the Alexander Palace grounds, and got this photo of the main gate to the Catherine Palace courtyard.

This would have been the carriage entrance and thus the "public" side of the palace. The long flat facade facing the gardens would have been the "private" side, visible and accessible only to people already admitted to the palace itself.

Here are two views of the facade facing the courtyard, the first taken through the fence, to the left of the gate shown above. We continued on past the main gate and into the courtyard by a smaller gate—the tourist entrance.

Here are two views of the facade facing the courtyard, the first taken through the fence, to the left of the gate shown above. We continued on past the main gate and into the courtyard by a smaller gate—the tourist entrance.

The photo at the right is a nearer view of part of the facade, next to the door through which we entered the palace. Alexei explained that the figures holding up the columns that in turn support the roof are "Atlases." I had not realized that "caryatids" are exclusively female, whereas these figures are male.

Inside, our first task was to slip these disposable paper (tyvek?) slippers over our shoes, where they were held in place by elastic around the ankles. They were one-size-fits-all, i.e., large, so we had to be careful throughout the tour not to step on each others floppy heels and toes.

Inside, our first task was to slip these disposable paper (tyvek?) slippers over our shoes, where they were held in place by elastic around the ankles. They were one-size-fits-all, i.e., large, so we had to be careful throughout the tour not to step on each others floppy heels and toes.

The photo at the right shows the reason for the slippers—every room in the palace is graced by a parquet floor of a different design. We were there on a nice dry day, so all we brought with us was dust and maybe a little sand, but if it had rained or if it were a snowy, slushy winter day, we would collectively have tracked pounds of mud, gravel, and snow-melt through the place. They don't bother at the Hermitage, but we encountered these slippers in several other palaces.

We were shown room after room, each magnificently decorated and individually named and, yes, each with its unique parquet floor. Floods of information was available about each one, and I couldn't keep up. If you want more info, though, just Google. For example, Googling "green dining room catherine palace russia" brings up a Wikipedia page dedicated to that room alone and giving reams of detail about it, its history, its decor, and its furnishings, in addition to multiple images from different angles.

We were shown room after room, each magnificently decorated and individually named and, yes, each with its unique parquet floor. Floods of information was available about each one, and I couldn't keep up. If you want more info, though, just Google. For example, Googling "green dining room catherine palace russia" brings up a Wikipedia page dedicated to that room alone and giving reams of detail about it, its history, its decor, and its furnishings, in addition to multiple images from different angles.

The names were mainly based on function of decor—the blue room, the gold room, the white room, the large dining room, the grand staircase, etc. Without the names, life there would have been bewildering, I imagine. "Jeeves, today I'd like tea served in the fourth room after one with the billiard table, headed northeast."

At the right here is another of the parquet floors.

Here's what I call the gold room, as that's the dominent color of its decor. Note the parquet.

Here's what I call the gold room, as that's the dominent color of its decor. Note the parquet.

In addition to the beautiful floors, each room had an elaborately shaped ceiling with a fresco in the center. Elizabeth loved Rococo, and it shows.

—

This large dining room was set as though for a Christmas-season dinner, on a table in the shape of some important insignia, which I can't remember and can't make out in the photo. Perhaps the double-headed eagle? It also shows off one of the many sets of dishes that the various tsars and tsarinas commissioned.

This large dining room was set as though for a Christmas-season dinner, on a table in the shape of some important insignia, which I can't remember and can't make out in the photo. Perhaps the double-headed eagle? It also shows off one of the many sets of dishes that the various tsars and tsarinas commissioned.

On one wall of the dining room was this massive tiled stove, which heated the room. I know that in Austria, where such stoves were common in the historical palaces, they were serviced from behind—servants circulated through passages within the walls to fuel them and remove the ashes—but I can see a metal door on the front of this one, so perhaps that wasn't the case here. The guides spoke of the beautiful delft tiles with which the stoves were clad but did not mention how they functioned.

—

Here, at the left, is the interior of Catherine the Great's the long, lacy gallery, with sunlight streaming in on both sides. It must have been a wonderful place to go for a comfortable stroll on a bitterly cold winter's day. I know people who would take one look and immediately calculate mentally the size of it in African-violet units—you could put fully 70,000 African violets in there!

Here, at the left, is the interior of Catherine the Great's the long, lacy gallery, with sunlight streaming in on both sides. It must have been a wonderful place to go for a comfortable stroll on a bitterly cold winter's day. I know people who would take one look and immediately calculate mentally the size of it in African-violet units—you could put fully 70,000 African violets in there!

In the middle of the gallery, behind the golden ropes, two costumed figures were wandering. Here, they had stopped to chat with a tourist (not one of our group). I don't know wehther they're always there, as part of the furnishings, or whether some special event had brought them.

—

Here, at the left, is the grand staircase. At the right is part of the decor of its walls—large porcelain vases on little ledges built specially for them. Below them in another rondel, this one framing a wall clock.

Here, at the left, is the grand staircase. At the right is part of the decor of its walls—large porcelain vases on little ledges built specially for them. Below them in another rondel, this one framing a wall clock.

—

—

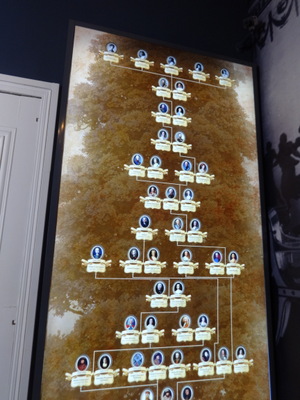

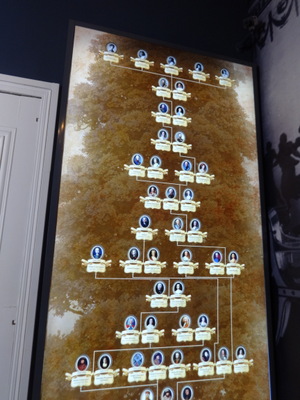

On the wall in a hallway, I found this Romanov family tree, on which each twig includes a miniature portrait of the person it represents. I couldn't get it all into one shot, so this is only the upper (later) portion, ending at the top with Nicholas II and Alexandra and, above them, their five children. Catherine the Great is the right-most image in the 7th row from the top.

On the wall in a hallway, I found this Romanov family tree, on which each twig includes a miniature portrait of the person it represents. I couldn't get it all into one shot, so this is only the upper (later) portion, ending at the top with Nicholas II and Alexandra and, above them, their five children. Catherine the Great is the right-most image in the 7th row from the top.

The photo at the right illustrates the way in which paintings were often hung in homes and palaces of the time. These are painted right onto the wall, but even collectors of individual framed paintings hung them edge-to-edge to cover the entire surface. I'm sure that's a carry-over from the arrangement of icons in the churches. Russians hadn't yet gotten used to the idea of paintings as individual objects that might be featured singly, surrounded by space.

The stove in this room had no door on the front, so it must have been serviced from behind the wall.

In this little rotunda, formed where doors branched off in several directions, the dome had been painted in "grisaille" with a variety of images—an interesting mix of musical instruments and weapons of war.

In this little rotunda, formed where doors branched off in several directions, the dome had been painted in "grisaille" with a variety of images—an interesting mix of musical instruments and weapons of war.

The green dining room, a much smaller one, intended for intimate parties of only a dozen or so, the ceiling was uncharacteristically plain.

The only room in which we could not take photos was the amber room.

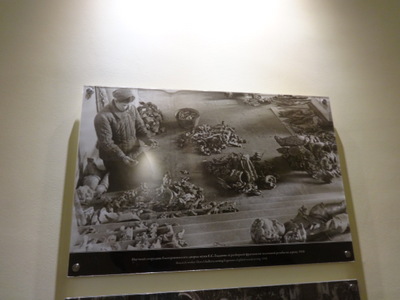

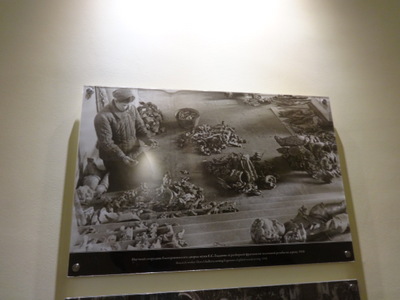

In another hallway, the walls had been set aside for display of photos of the palace after World War II. The four at the left are hard to make out, but they show damage to the exterior, the grand staircase, and several of the large room. All the windows are broken, so snow is drifted in some of the rooms. All the precious objects are gone or broken; decor has been stripped off the walls and railings and bannisters toppled.

In another hallway, the walls had been set aside for display of photos of the palace after World War II. The four at the left are hard to make out, but they show damage to the exterior, the grand staircase, and several of the large room. All the windows are broken, so snow is drifted in some of the rooms. All the precious objects are gone or broken; decor has been stripped off the walls and railings and bannisters toppled.

In the photo at the right, despite the annoying glare off the glass, you can see heaps of small objects—mostly broken cherubs and pieces of foliage-themed chandeliers—that have been brought together and sorted so that restoration can begin. Surprisingly, the Soviets invested a huge amount in restoring the palace after World War II.

At the left here is the "white room." I wish I'd gotten a wider shot of it. It's merely pretty here, but the effect of this immense room, all in stark white with dramatic red window shades, was stunning.

At the left here is the "white room." I wish I'd gotten a wider shot of it. It's merely pretty here, but the effect of this immense room, all in stark white with dramatic red window shades, was stunning.

Then it was back outside and back to the buses. On the way, we stopped briefly at this statue to Pushkin. I believe I mentioned somewhere earlier in the blog that his given name, patronymic, and family name are each followed by the suffice "oo" in the inscription—that's the case ending indicating "to," as in "[Dedicated] to Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin."

Pushkin spent about 10 years here, at the local college; the Pushkin family dacha is next door to the palace. When Peter the Great visited the French court in 1710, he encountered a black Ethiopian named Abram Petrovich Gannibal (i.e. "Hannibal"), who had been kidnapped from Africa and later presented as a gift to the French king. Peter asked and got permission to invite him to the Russian court. He came, married a Russian girl, and became the great grandfather of Pushkin.

Pushkin himself died at age 37, killed in a duel with a French officer who had an affair with Pushkin's wife. The officer was banished, but within the 48 hours he had to get out of dodge, married Pushkin's wife's sister and took her with him.

These are the anecdotes always brought up when Pushkin's name is mentioned.

Back on the buses and driving the 30 km back to St. Petersburg, we learned more.

- The Catherine Palace became public property in 1919, after the revolution. During the 1920's, it was protected as a museum and opened to the public.

- Slavery persisted in Russia until 1861, so some of the palace servants were serfs. In western Europe, the term serf is reserved for people bound to the land and therefore bought and sold with it. In Russia, apparently, that wasn't true of all serf. Up to some date in Russia's history, serfs could be bought and sold individually, with no land attached, and a land-owner might move serfs from one estate to another within his holdings. Even what we would call "household slaves" were considered serfs.

- The lapis lazuli used in the palace, for urns and decoration, came from from Afganistan and Turkey.

- The throne room is 80,000 suare feet; its ceiling is the largest canvas ever painted in Russia. All The gilding is real gold leaf, not ormoulu.

- From the founding in 1744 of the first Russian porcelain factory, the royal family monopolized its production, commissioning set after ever larger set of dishes.

- Pushkin is currently a town of about 40,000 people. It is home to a large agricultural academy—we saw groups of its students working in the palace gardens. Some of the towns population work at the palaces, some are at the Ag Academy, and some commute to St. Petersburg.

- According to Alexei, speaking with tongue in cheek, the people here can distinguish up to 256 shades of grey but only two of blue. Describing the climate, he told us that Russians live with nine month of anticipation followed by three months of disappointment.

Back on the Akun, it was lunch time. At the left here is my selection from the salad bar. The feature hors d'oeuvres of the day were Russian sausages and sauerkraut (at about 2 o'clock on the plate; the sausages were way better this way than as a breakfast food) and artichoke stuffed with cream cheese (just what it looks like—a marinated artichoke wedge with a puff of cream cheese piped on top). Unmentioned on the menu but among the best choices were these slices of dark bread with horseradish cream and slices of rare roast beef!

Back on the Akun, it was lunch time. At the left here is my selection from the salad bar. The feature hors d'oeuvres of the day were Russian sausages and sauerkraut (at about 2 o'clock on the plate; the sausages were way better this way than as a breakfast food) and artichoke stuffed with cream cheese (just what it looks like—a marinated artichoke wedge with a puff of cream cheese piped on top). Unmentioned on the menu but among the best choices were these slices of dark bread with horseradish cream and slices of rare roast beef!

At the right is the fish and chips with pea puré, tartar sauce, and "malt" vinegar (which looked a lot like red-wine vinegar to me), which I think three of us had. Rachel's allergic to fish and wasn't interested in the chicken Caesar wrap, so she had the cream of (i.e., puréed) vegetable soup with roasted sesame seeds. Nobody ordered the rigatoni with pesto.

At the left here is Ev's idea of a selection from the salad bar: three olives and a little heap of pumpkin seeds. I think he may already have eaten one of the open-faced roast-beef sandwiches.

At the left here is Ev's idea of a selection from the salad bar: three olives and a little heap of pumpkin seeds. I think he may already have eaten one of the open-faced roast-beef sandwiches.

At the right are Ev and Rachel, clearly enjoying themselves.

The dessert choices were carrot cake (left) and Ice cream coup Denmark (chocolate and vanilla ice cream with chocolate sauce; right).

The dessert choices were carrot cake (left) and Ice cream coup Denmark (chocolate and vanilla ice cream with chocolate sauce; right).

Figs must have been very expensive, as this is the only form in which we got them—in little wedges doled out as a garnish on other things. In Portugal they put big bowls of them out on the breakfast buffet.

At 2 p.m., we were back on the buses and headed downtown for our St. Petersburg city tour. We chose the moderately strenuous "ordinary" tour (by bus and on foot) as opposed to the more strenuous "up close" tour (by metro and on foot). On many occasions, we were also offered a "leisurely" option for folks who wanted less walking.

At 2 p.m., we were back on the buses and headed downtown for our St. Petersburg city tour. We chose the moderately strenuous "ordinary" tour (by bus and on foot) as opposed to the more strenuous "up close" tour (by metro and on foot). On many occasions, we were also offered a "leisurely" option for folks who wanted less walking.

As we approached the middle of town, we passed two ships on the far bank of the river. The one shown here at the left might be a real ship, though I was never sure. The navy is supposed to have a real sailing ship anchored somewhere near here, but I don't really think this is it.

The one at the right is definitely not a real ship; it's got "Restaurant" painted on it in big letters in several places, and our tour guide assured us it was built for that purpose and has never been afloat. Picturesque though.

The center of St. Petersburg is the point at which the Neva splits to flow to either side of Vasilevsky Island (and then into the Gulf of Finland. The Winter Palace/Hermitage is on the south bank, the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress on the north side, and in the middle the spit (i.e., pointed end) of the island. On the spit are two huge barn-red "rostral columns," out of which jut the prows (rostra) of ships. I don't think these are real ships' prows, but apparently the Romans actually used to saw the prows off captured enemy ships and mount them on columns in this fashion. They are not my idea of the height of elegance, but to each his own . . .

The center of St. Petersburg is the point at which the Neva splits to flow to either side of Vasilevsky Island (and then into the Gulf of Finland. The Winter Palace/Hermitage is on the south bank, the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress on the north side, and in the middle the spit (i.e., pointed end) of the island. On the spit are two huge barn-red "rostral columns," out of which jut the prows (rostra) of ships. I don't think these are real ships' prows, but apparently the Romans actually used to saw the prows off captured enemy ships and mount them on columns in this fashion. They are not my idea of the height of elegance, but to each his own . . .

At the top of each column is a light (now gas-fired) so that they can be used as lighthouses, but they are now only lit up for celebrations and other special occasions.

At the right is King Triton sitting at the bottom of one of the columns. A female figure sits on the other side.

The bus stopped for a while on the spit so that we could get out and look around. Here at the left is the view of the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress, which is not, we were reminded, a kremlin. St. Petersburg has never had a kremlin. It seems to me to have all the elements—a fortress with a cathedral inside, etc.—but I guess it's never been the seat of government. Maybe that's the difference. The tall yellow spire marks the cathedral. It's the tallest building in St. Petersburg, and the statue on top is the spirit of navigation.

The bus stopped for a while on the spit so that we could get out and look around. Here at the left is the view of the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress, which is not, we were reminded, a kremlin. St. Petersburg has never had a kremlin. It seems to me to have all the elements—a fortress with a cathedral inside, etc.—but I guess it's never been the seat of government. Maybe that's the difference. The tall yellow spire marks the cathedral. It's the tallest building in St. Petersburg, and the statue on top is the spirit of navigation.

The river is covered with "bateaux mouche"–style tour boats. The quai is covered with ice cream stands, each with a noisy gasoline-fired generator. A few more costumed figures appeared, strolling up the ramp that leads down to the river side. Again, I have no idea what they were there for.

Next, we reboarded the buses for the short trip over to the fortress, where we were once again free to stroll around. Flying ants are buzzing all over the inside of the fortress. At the left is a view of the cathedral from inside the walls.

Next, we reboarded the buses for the short trip over to the fortress, where we were once again free to stroll around. Flying ants are buzzing all over the inside of the fortress. At the left is a view of the cathedral from inside the walls.

The photo at the right is the boat house, a pavillion Peter the Great had built to house Grand Boat of Russia, a small sailing dinghy in which he learned the rudiments of sailing. We didn't get to go inside to see the replica that has replaced it. Peter considered it the grandfather of the Russian navy.

The fortress also houses the mint, a long, low building with "Mint" is large letters over the door.

As you can see from these shots of the interior, it differs a good deal from most Russian Orthodox churches in its layout and decor.

As you can see from these shots of the interior, it differs a good deal from most Russian Orthodox churches in its layout and decor.

Because of its military nature, the icon stand looks like a triumphal arch. It was undamaged during the war.

This cathedral houses the tombs of all Russian rulers from Peter the Great through the end of the Romanov dynasty, as well as many of their relatives, 53 graves in all.

Peter was the one who specified that all the tombs should be alike, and they are, with two exceptions: that of Alexander II, who abolished slavery, is larger and made of green jasper; that of his wife, also larger is made of red rhodonite. Peter's own grave is distinguised by a bust of him standing behind it.

Peter was the one who specified that all the tombs should be alike, and they are, with two exceptions: that of Alexander II, who abolished slavery, is larger and made of green jasper; that of his wife, also larger is made of red rhodonite. Peter's own grave is distinguised by a bust of him standing behind it.

The panel shown at the right is a photograph of a side chapel that was roped off. It houses the remains of Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, their five children, and five other people who died with them. Because the bones are all mingled, they lie in a common tomb inside the room. Plaques on the wall commemorate each individual, and only two blanks remain to be filled in. DNA testing began in the 1990s is still ongoing. It has so far succeeded in identifying remains of all members of the family except one of the daughters and the son, Alexei, so their burial dates remain to be added to their plaques. Note that the unidentified daughter is not Anastasia; she has been found, so all those pretenders really were pretenders.

Our next stop was to view the Cathedral on the Spilled Blood. In 1881, Alexander II was killed when a nihilist threw a bomb into his carriage, and Alexander III, his heartbroken son, had a cathedral built on the spot.

Our next stop was to view the Cathedral on the Spilled Blood. In 1881, Alexander II was killed when a nihilist threw a bomb into his carriage, and Alexander III, his heartbroken son, had a cathedral built on the spot.

At the left here is a section of the ornate wrought iron fence around it, and at the right a view of the cathedral itself. It's the only church in St. Petersburg built in this Byzantine style so common in the rest of Russia. We didn't have time to go inside.

Before we even arrived in St. Petersburg, we had been warned to beware of pickpockets. Unfortunately, they were very active. While we were admiring the cathedral, Ev was double-teamed by thieves, one of whom got right in his face, gesticulating wildly and urging him to look at his souvenir stand, while another jostled him from behind and got his wallet, even though Ev had moved it to his front pocket. Talk about a hassle! During the whole rest of the trip, Ev had to spend hours on the phone and the internet cancelling credit cards, freezing credit, etc. Needless to say, we were very glad of our "hidden pockets," and for the rest of our time in the city, I carried my "healthy back" bag with the steel-reinforced strap across my body and in front, essentially cradled in my arms at all times.

Fortunately, we were able to cover their expenses for the rest of the trip (although at least three others among the passengers approached them privately to offer help), but what a nuisance!

Passing back through town, I got this hasty shot of the Kazan Cathedral (left) and at our next stop this photo of St. Isaac's Cathedral (right).

Passing back through town, I got this hasty shot of the Kazan Cathedral (left) and at our next stop this photo of St. Isaac's Cathedral (right).

Strangely, I had with me a photo of St. Isaac's clipped from the Tallahassee Democrat shortly before we left for Russia. The mayor has announced plans to return the cathedral, now a city museum, to the church in 2018. The resulting protests were big enough to make our local newspaper! Just out of the frame to the right is the hotel, the Angleterre, in which we stayed for two nights after the cruise.

Given a few minutes to walk around the palace gardens (now a park, behind me as I photographed St. Isaac's), I got these shots of decorative flower beds, two of a long series.

Given a few minutes to walk around the palace gardens (now a park, behind me as I photographed St. Isaac's), I got these shots of decorative flower beds, two of a long series.

The one at the left depicts a blue tit. To match the image in plants to the one on the explanatory panel, start with the diagonal line representing the branch and the bird's two brown feet.

The one at the right shows a tree with a rainbow. In this case, the image in flowers is easier to see than the one on the panel.

On the bus ride back to the ship, we learned more miscellaneous stuff:

- The population of St. Petersburg is about 5 million.

- A small apartment with a view runs about $1 million.

- The city draws 3 to 4 million tourists a year.

- It's built on 42 islands and has 80 waterways. I'm pretty sure he said it has more bridges than Amsterdam and Venice combined.

- Prince Alexander Nevsky is the largest monastary in town. Nevsky (which means "of the Neva") lived in the 13th century and was cannonized in 15th. He defended Russia from Crusaders who wanted to make it Roman catholic (who knew crusaders went north?!). (Other sources say he repelled German and Swedish invaders, but David tells me that that was the same thing; the crusaders were the "Teutonic Knights.") The main street in town is "Nevskii Prospect," named for him.

- During World War I, Dagmar (mother of Nicholas II) was evacuated back to her native Denmark through the Crimea aboard a British battleship. She stayed on there after the revolution and eventually died and was buried there, even though she wished to be buried in Russia. After the U.S.S.R. fell, her grave was moved back to the cathedral in the fortress, quite recently, in 2006 or so.

- No Romanovs remain in Russia. They're all in France or other European countries; some are even in south America. Grand Duke George Romanov, heir to the throne, lives in France.

- Russia is not open to refugees from Syria or anywhere else, but immigrants from former Soviet republics are welcome, and many come. Since the 1990s, emigration is also permitted, especially Jewish emigration. Afer the collapse of the Soviet regime, many people with German roots from the Volga and Kazakstan regins emigrated. The Germans would take them all back if they could show they were descended from those who migrated to Russia with Catherine the Great. Ca. 145 million people have left Russia (can that be right?); about 30 million Russians live abroad, but 150 million are still here.

- Russians can go to Israel or to south American without any visa; also to Mexico if you don't stay more than a month. Getting a tourism visa to Europe is easy. To Canada, US, New Zealand, Japan, Canada it's more complicated, but seems to work pretty well (Alexei says he interviewed for two minutes with the consul and got a letter of invitation).

- Visas to the U.S. are more difficult. At 16, Alexei's daughter had trouble getting a visa to go to Chicago for school. She was refused twice without explanation. The third application worked, but each application cost $300, nonrefundable. Later, with her company's support, she finally got a business visa.

- The large orange building, the Palace of Unhappiness, is the only fortified castle in the city. Paul I was paranoid about assissination and was in fact assassinated in his own bed, in the fortified castle, only 40 days after moving in (after ruling for 4 years, 4 months, and 4 days).

- Catherine the Great forbade tall buildings in downtown St. Petersburg, but it turns out that

the soil isn't well suited for the weight of tall buildings anyway.

- St. Isaac of Dalmatia was canonized in Byzantium in the 5th century (and was no relation to Abraham and Sarah). He got a cathedral here because Peter the Great was born on St. Isaac's day.

- Fabergé started his business here in 1842 and his descendents closed it down in 1917 and went to Switzerland.

- If you go to a movie at 10 or 11 a.m., it's maybe $2.00; the same movie at 11 p.m. would be $16 to $20.

- Gas here is more or less the same price as in the U.S.

- Twenty daily trains leave St. Petersburg for Moscow. During the daytime, they are mainly TGVs, but at night slower overnight trains (8-hour sleepers) make the trip.

- The Hermitage has 3 million items in its collection.

Every time we drove anywhere to or from the ship, we passed this intriguing structure, and I never got a chance to ask what the heck it was. I thought it must be some sort of weird nuclear power plant, being right behind the pair of smoke stacks as it was. When I got home to Tallahassee, I looked it up (by the simple expedient of Googling "flying saucer building st. petersburg russia) and learned that it is in fact the city's administrative center, "Nevskaya ratusha." It just happens to be lined up behind the smoke stacks so that it looks as though they're together.

Every time we drove anywhere to or from the ship, we passed this intriguing structure, and I never got a chance to ask what the heck it was. I thought it must be some sort of weird nuclear power plant, being right behind the pair of smoke stacks as it was. When I got home to Tallahassee, I looked it up (by the simple expedient of Googling "flying saucer building st. petersburg russia) and learned that it is in fact the city's administrative center, "Nevskaya ratusha." It just happens to be lined up behind the smoke stacks so that it looks as though they're together.

As we pulled up to the dock, we saw all four of Viking's Russian ships stacked up (Truvor, Ingvar, Helgi, and Akun); we were third or fourth out from the dock.

For dinner, back on the ship, I tried the Greek salad with feta cheese (the chef is Greek, right?). It was a good salad, but the olives were the plain watery kind out of a can, not what I would call Greek olives. And the feta was the consistency of soft, spreadable fresh goat cheese (though less flavorful).

David ordered the "pepper-seared salmon" with citrus vinaigrette, which he declared very good.

Ev's cheese plate was a Bavarian bleu and Gouda with apricot chutney.

I don't think anyone ordered the Tuna salad with string beans, poatoes, and boiled eggs or the cream of bell pepper soup with pesto croutons.

My main course was crispy sea bass fillet with lemongrass sauce (shown at right). Very good, but not at all crispy.

David had the pork tenderloin and dried plums wrapped in bacon with potato croquettes, sautéed broccoli and Marsala sauce. It looked delicious.

Nobody ordered the vegetable quiche with saffron sauce and microgreen salad.

The dessert choices were banana bread pudding and profiteroles. I ordered the former and found myself envying everyone else's profiteroles. It was one of those bread puddings where the chef threw the eggs, milk, seasonings, and bread into a blender and whizzed them smooth before baking them into a repellent, glutinous puck. Icky.

The profiteroles were actually filled with pastry cream rather than ice cream—an improvement in my opinion, though definitely not traditional, but Rachel was incensed. I should have just shoved the bread pudding aside and asked for profiteroles instead.

And the day wasn't over yet! On the river bank, just a few yards (as promised) from the ship, was a large square white tent, like the ones they set up for big weddings. In it was a stage, and we were signed up for the evenings performance of Cossack music and dance.

And the day wasn't over yet! On the river bank, just a few yards (as promised) from the ship, was a large square white tent, like the ones they set up for big weddings. In it was a stage, and we were signed up for the evenings performance of Cossack music and dance.

And who, I wanted to know, where the Cossacks anyway. I'd heard of them all my life but had no idea beyond that. They are, it turns out, a people, excellent warriors, who settled on the steppes and formed a sort of buffer between the organized towns of Russia to the north and the nomadic tribes to the south,

The Tsar liked having them there, defending Russia from incursions by raiding parties and whatnot, so he accorded them special privileges and freedoms. In return, they were fiercely loyal to the Tsar and fought valiently on his side during the revolution and ensuing civil war.

At the left here is Margo, mike in hand, introducing the troupe of singers and dancers who would entertain us. The photos in the brochures show a cast of thousands with smoke effects and spears. We didn't exactly get that, but it was a great show anyway.

At the right are two of the three who did most of the singing in the performance, though they joined in with the dancing as well.

Strung on rails below the edge of the stage, you can make out large, richly colored fringed shawls, which turned out to be for sale during intermission.

The troupe seemed to consist of about a dozen dancers and singers, plus four instrumental musicians. They went throught several costume changes, alternating dancing numbers with singing and instrumental numbers, waving swords, etc.

The troupe seemed to consist of about a dozen dancers and singers, plus four instrumental musicians. They went throught several costume changes, alternating dancing numbers with singing and instrumental numbers, waving swords, etc.

And yes, they did the famous dance where guys in deep-knee-bend position kick their legs alternately out in front of them, and they did it pretty darned well, too!

At intermission, Rachel bought one of the shawls, consulting me, David, Ev, and several innocent bystanders over the choice of color. In my opinion, she settled on exactly the right one, both for intrinsic beauty and for complementing her own coloration.

Midway through the performance, the singers were startled and chased off the stage by the arrival of a pair of bulkily fur-clad dwarves locked in a desperate wrestling match. They rolled and tumbled around the stage, pushing and shoving each other. At one they fell off the stage and wrestled back and forth in front of it and then up and down the center aisle, bashing into tourists sitting there and jostling their chairs.n They somehow managed to wrestle each other back up the steps to the stage where, in the end, they were of course revealed to be a single dancer bent double, with boots on his hands and feet and heads mounted on his back.

Midway through the performance, the singers were startled and chased off the stage by the arrival of a pair of bulkily fur-clad dwarves locked in a desperate wrestling match. They rolled and tumbled around the stage, pushing and shoving each other. At one they fell off the stage and wrestled back and forth in front of it and then up and down the center aisle, bashing into tourists sitting there and jostling their chairs.n They somehow managed to wrestle each other back up the steps to the stage where, in the end, they were of course revealed to be a single dancer bent double, with boots on his hands and feet and heads mounted on his back.

It was a truly impressive performance, and I assume it must be some sort of Cossack tradition. The dancer was the one down on one knee to the left of the woman who's skirt is flaring wide in the second pair of photos of the troupe.

Once the wrestling-dwarf number was over, I leaned forward to the lady sitting in front of me, in the first row, who had been pretty soundly buffeted (laughing all the while), and reminded her of my answer when she had earlier asked me why we sat in the second row when the first was empty, and several seats in rather than on the center aisle—we are always guarding against audience participation!

Once the wrestling-dwarf number was over, I leaned forward to the lady sitting in front of me, in the first row, who had been pretty soundly buffeted (laughing all the while), and reminded her of my answer when she had earlier asked me why we sat in the second row when the first was empty, and several seats in rather than on the center aisle—we are always guarding against audience participation!

At the left is the band. I've forgotten what the guy on the left played, and I didn't get a photo, but the rest are, left to right, drums, accordion, and bass balaika. If you Google "viking cossack performance St. petersburg russia," you'll get better photos than I was able to, with the speakers and edge of the stage in the way. You can recognize some of the same dancers.

After the performance, strolling back to the ship, I got this shot of the Bolshoi Obukhovsky Suspension Bridge, the newest bridge in St. Petersburg and the only one that isn't a drawbridge. That's the Viking Truvor at the right; it was that ship's turn to be against the quai that day.

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

We spent Tuesday afternoon and most of that night following the Svir River to Lake Ladoga, then across the lake and out the other side on the Neva River, our final body of water. At some point during the wee hours, we docked in St. Petersburg. Here, at the left, is the view across the river from the dining room when I came to breakfast.

We spent Tuesday afternoon and most of that night following the Svir River to Lake Ladoga, then across the lake and out the other side on the Neva River, our final body of water. At some point during the wee hours, we docked in St. Petersburg. Here, at the left, is the view across the river from the dining room when I came to breakfast.

While I ate breakfast, I got a few more shots. Here, at the left, is the Saint Petersburg in front of the same bridge.

While I ate breakfast, I got a few more shots. Here, at the left, is the Saint Petersburg in front of the same bridge.

Not all the river traffic was cruise ships—here's a load of logs on its way somewhere—but a lot of it was. When it was time to catch the buses for our 8:00 a.m. tour of the Catherine Palace, we found that the Akun was moored outboard of four other ships! We had quite a trek just to reach the pier.

Not all the river traffic was cruise ships—here's a load of logs on its way somewhere—but a lot of it was. When it was time to catch the buses for our 8:00 a.m. tour of the Catherine Palace, we found that the Akun was moored outboard of four other ships! We had quite a trek just to reach the pier.

Our bus dropped us off near one end of the long axis of the palace, about where the red lettering is in the map at the right. We walked around to the left toward the palace and encountered this yellow-and-white building, which was the royal lycée. Pushkin was one of its first students. It was (and still is) actually connected to the palace by an enclosed elevated walkway, which you can just see to the left of the building.

Our bus dropped us off near one end of the long axis of the palace, about where the red lettering is in the map at the right. We walked around to the left toward the palace and encountered this yellow-and-white building, which was the royal lycée. Pushkin was one of its first students. It was (and still is) actually connected to the palace by an enclosed elevated walkway, which you can just see to the left of the building.

Continuing around the lycée, we first saw the palace end-on, but as we continued, more and more of it came into view, until we could see Restrelli's entire facade, which is 400 m wide.

Continuing around the lycée, we first saw the palace end-on, but as we continued, more and more of it came into view, until we could see Restrelli's entire facade, which is 400 m wide.

We walked along the facade until we reached the midpoint, then turned away from the palace to start down the central axis of the gardens, toward the "hermitage" at what initially looks like its far end. In fact, the gardens continue as far again beyond it—Alexei said that walking the entire long axis of the gardens (from upper left to lower right on the map) takes about 45 minutes.

We walked along the facade until we reached the midpoint, then turned away from the palace to start down the central axis of the gardens, toward the "hermitage" at what initially looks like its far end. In fact, the gardens continue as far again beyond it—Alexei said that walking the entire long axis of the gardens (from upper left to lower right on the map) takes about 45 minutes.

From the hermitage, we walked back up the axis toward the palace and then to our left to walk along the edge of the large lake. I think the building at the left here is the one marked "grotto" on the map, right on the edge of the lake.

From the hermitage, we walked back up the axis toward the palace and then to our left to walk along the edge of the large lake. I think the building at the left here is the one marked "grotto" on the map, right on the edge of the lake.

Here's an end-on view of the long lacy gallery, from the down-hill side. The gallery, designed by Scotsman Charles Cameron, we added during the reign of Cathering the Great. She lived here permanently during the late part of her life. It seems to me that they could at least have painted the souvenir shop the right shade of blue to match the palace!

Here's an end-on view of the long lacy gallery, from the down-hill side. The gallery, designed by Scotsman Charles Cameron, we added during the reign of Cathering the Great. She lived here permanently during the late part of her life. It seems to me that they could at least have painted the souvenir shop the right shade of blue to match the palace!

We followed the side of the gallery, then the end wall of the palace, until we emerged into the parking lot that surrounds the curved side of the palace. This map shows the layout of the Alexander Palace and its grounds, adjacent to the Catherine Palace. It was commissioned by Catherine the Great for her favorite grandson, later Alexander I, and was later the favorite residence of Nicholas II, the ill-fated last Romanov tsar, and his family. Rasputin was initially buried on the grounds, but a mob soon dug him up, burned the remains, and scattered the ashes in the Neva. I think the palace is still under restoration—we didn't get to go in.

We followed the side of the gallery, then the end wall of the palace, until we emerged into the parking lot that surrounds the curved side of the palace. This map shows the layout of the Alexander Palace and its grounds, adjacent to the Catherine Palace. It was commissioned by Catherine the Great for her favorite grandson, later Alexander I, and was later the favorite residence of Nicholas II, the ill-fated last Romanov tsar, and his family. Rasputin was initially buried on the grounds, but a mob soon dug him up, burned the remains, and scattered the ashes in the Neva. I think the palace is still under restoration—we didn't get to go in.

Here are two views of the facade facing the courtyard, the first taken through the fence, to the left of the gate shown above. We continued on past the main gate and into the courtyard by a smaller gate—the tourist entrance.

Here are two views of the facade facing the courtyard, the first taken through the fence, to the left of the gate shown above. We continued on past the main gate and into the courtyard by a smaller gate—the tourist entrance.

Inside, our first task was to slip these disposable paper (tyvek?) slippers over our shoes, where they were held in place by elastic around the ankles. They were one-size-fits-all, i.e., large, so we had to be careful throughout the tour not to step on each others floppy heels and toes.

Inside, our first task was to slip these disposable paper (tyvek?) slippers over our shoes, where they were held in place by elastic around the ankles. They were one-size-fits-all, i.e., large, so we had to be careful throughout the tour not to step on each others floppy heels and toes.

We were shown room after room, each magnificently decorated and individually named and, yes, each with its unique parquet floor. Floods of information was available about each one, and I couldn't keep up. If you want more info, though, just Google. For example, Googling "green dining room catherine palace russia" brings up a Wikipedia page dedicated to that room alone and giving reams of detail about it, its history, its decor, and its furnishings, in addition to multiple images from different angles.

We were shown room after room, each magnificently decorated and individually named and, yes, each with its unique parquet floor. Floods of information was available about each one, and I couldn't keep up. If you want more info, though, just Google. For example, Googling "green dining room catherine palace russia" brings up a Wikipedia page dedicated to that room alone and giving reams of detail about it, its history, its decor, and its furnishings, in addition to multiple images from different angles.

Here's what I call the gold room, as that's the dominent color of its decor. Note the parquet.

Here's what I call the gold room, as that's the dominent color of its decor. Note the parquet.

This large dining room was set as though for a Christmas-season dinner, on a table in the shape of some important insignia, which I can't remember and can't make out in the photo. Perhaps the double-headed eagle? It also shows off one of the many sets of dishes that the various tsars and tsarinas commissioned.

This large dining room was set as though for a Christmas-season dinner, on a table in the shape of some important insignia, which I can't remember and can't make out in the photo. Perhaps the double-headed eagle? It also shows off one of the many sets of dishes that the various tsars and tsarinas commissioned.

Here, at the left, is the interior of Catherine the Great's the long, lacy gallery, with sunlight streaming in on both sides. It must have been a wonderful place to go for a comfortable stroll on a bitterly cold winter's day. I know people who would take one look and immediately calculate mentally the size of it in African-violet units—you could put fully 70,000 African violets in there!

Here, at the left, is the interior of Catherine the Great's the long, lacy gallery, with sunlight streaming in on both sides. It must have been a wonderful place to go for a comfortable stroll on a bitterly cold winter's day. I know people who would take one look and immediately calculate mentally the size of it in African-violet units—you could put fully 70,000 African violets in there!

Here, at the left, is the grand staircase. At the right is part of the decor of its walls—large porcelain vases on little ledges built specially for them. Below them in another rondel, this one framing a wall clock.

Here, at the left, is the grand staircase. At the right is part of the decor of its walls—large porcelain vases on little ledges built specially for them. Below them in another rondel, this one framing a wall clock.

On the wall in a hallway, I found this Romanov family tree, on which each twig includes a miniature portrait of the person it represents. I couldn't get it all into one shot, so this is only the upper (later) portion, ending at the top with Nicholas II and Alexandra and, above them, their five children. Catherine the Great is the right-most image in the 7th row from the top.

On the wall in a hallway, I found this Romanov family tree, on which each twig includes a miniature portrait of the person it represents. I couldn't get it all into one shot, so this is only the upper (later) portion, ending at the top with Nicholas II and Alexandra and, above them, their five children. Catherine the Great is the right-most image in the 7th row from the top.

In this little rotunda, formed where doors branched off in several directions, the dome had been painted in "grisaille" with a variety of images—an interesting mix of musical instruments and weapons of war.

In this little rotunda, formed where doors branched off in several directions, the dome had been painted in "grisaille" with a variety of images—an interesting mix of musical instruments and weapons of war.

In another hallway, the walls had been set aside for display of photos of the palace after World War II. The four at the left are hard to make out, but they show damage to the exterior, the grand staircase, and several of the large room. All the windows are broken, so snow is drifted in some of the rooms. All the precious objects are gone or broken; decor has been stripped off the walls and railings and bannisters toppled.

In another hallway, the walls had been set aside for display of photos of the palace after World War II. The four at the left are hard to make out, but they show damage to the exterior, the grand staircase, and several of the large room. All the windows are broken, so snow is drifted in some of the rooms. All the precious objects are gone or broken; decor has been stripped off the walls and railings and bannisters toppled.

At the left here is the "white room." I wish I'd gotten a wider shot of it. It's merely pretty here, but the effect of this immense room, all in stark white with dramatic red window shades, was stunning.

At the left here is the "white room." I wish I'd gotten a wider shot of it. It's merely pretty here, but the effect of this immense room, all in stark white with dramatic red window shades, was stunning.

Back on the Akun, it was lunch time. At the left here is my selection from the salad bar. The feature hors d'oeuvres of the day were Russian sausages and sauerkraut (at about 2 o'clock on the plate; the sausages were way better this way than as a breakfast food) and artichoke stuffed with cream cheese (just what it looks like—a marinated artichoke wedge with a puff of cream cheese piped on top). Unmentioned on the menu but among the best choices were these slices of dark bread with horseradish cream and slices of rare roast beef!

Back on the Akun, it was lunch time. At the left here is my selection from the salad bar. The feature hors d'oeuvres of the day were Russian sausages and sauerkraut (at about 2 o'clock on the plate; the sausages were way better this way than as a breakfast food) and artichoke stuffed with cream cheese (just what it looks like—a marinated artichoke wedge with a puff of cream cheese piped on top). Unmentioned on the menu but among the best choices were these slices of dark bread with horseradish cream and slices of rare roast beef!

At the left here is Ev's idea of a selection from the salad bar: three olives and a little heap of pumpkin seeds. I think he may already have eaten one of the open-faced roast-beef sandwiches.

At the left here is Ev's idea of a selection from the salad bar: three olives and a little heap of pumpkin seeds. I think he may already have eaten one of the open-faced roast-beef sandwiches.

The dessert choices were carrot cake (left) and Ice cream coup Denmark (chocolate and vanilla ice cream with chocolate sauce; right).

The dessert choices were carrot cake (left) and Ice cream coup Denmark (chocolate and vanilla ice cream with chocolate sauce; right).

At 2 p.m., we were back on the buses and headed downtown for our St. Petersburg city tour. We chose the moderately strenuous "ordinary" tour (by bus and on foot) as opposed to the more strenuous "up close" tour (by metro and on foot). On many occasions, we were also offered a "leisurely" option for folks who wanted less walking.

At 2 p.m., we were back on the buses and headed downtown for our St. Petersburg city tour. We chose the moderately strenuous "ordinary" tour (by bus and on foot) as opposed to the more strenuous "up close" tour (by metro and on foot). On many occasions, we were also offered a "leisurely" option for folks who wanted less walking.

The center of St. Petersburg is the point at which the Neva splits to flow to either side of Vasilevsky Island (and then into the Gulf of Finland. The Winter Palace/Hermitage is on the south bank, the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress on the north side, and in the middle the spit (i.e., pointed end) of the island. On the spit are two huge barn-red "rostral columns," out of which jut the prows (rostra) of ships. I don't think these are real ships' prows, but apparently the Romans actually used to saw the prows off captured enemy ships and mount them on columns in this fashion. They are not my idea of the height of elegance, but to each his own . . .

The center of St. Petersburg is the point at which the Neva splits to flow to either side of Vasilevsky Island (and then into the Gulf of Finland. The Winter Palace/Hermitage is on the south bank, the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress on the north side, and in the middle the spit (i.e., pointed end) of the island. On the spit are two huge barn-red "rostral columns," out of which jut the prows (rostra) of ships. I don't think these are real ships' prows, but apparently the Romans actually used to saw the prows off captured enemy ships and mount them on columns in this fashion. They are not my idea of the height of elegance, but to each his own . . .

The bus stopped for a while on the spit so that we could get out and look around. Here at the left is the view of the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress, which is not, we were reminded, a kremlin. St. Petersburg has never had a kremlin. It seems to me to have all the elements—a fortress with a cathedral inside, etc.—but I guess it's never been the seat of government. Maybe that's the difference. The tall yellow spire marks the cathedral. It's the tallest building in St. Petersburg, and the statue on top is the spirit of navigation.

The bus stopped for a while on the spit so that we could get out and look around. Here at the left is the view of the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress, which is not, we were reminded, a kremlin. St. Petersburg has never had a kremlin. It seems to me to have all the elements—a fortress with a cathedral inside, etc.—but I guess it's never been the seat of government. Maybe that's the difference. The tall yellow spire marks the cathedral. It's the tallest building in St. Petersburg, and the statue on top is the spirit of navigation.

Next, we reboarded the buses for the short trip over to the fortress, where we were once again free to stroll around. Flying ants are buzzing all over the inside of the fortress. At the left is a view of the cathedral from inside the walls.

Next, we reboarded the buses for the short trip over to the fortress, where we were once again free to stroll around. Flying ants are buzzing all over the inside of the fortress. At the left is a view of the cathedral from inside the walls.

As you can see from these shots of the interior, it differs a good deal from most Russian Orthodox churches in its layout and decor.

As you can see from these shots of the interior, it differs a good deal from most Russian Orthodox churches in its layout and decor.

Peter was the one who specified that all the tombs should be alike, and they are, with two exceptions: that of Alexander II, who abolished slavery, is larger and made of green jasper; that of his wife, also larger is made of red rhodonite. Peter's own grave is distinguised by a bust of him standing behind it.

Peter was the one who specified that all the tombs should be alike, and they are, with two exceptions: that of Alexander II, who abolished slavery, is larger and made of green jasper; that of his wife, also larger is made of red rhodonite. Peter's own grave is distinguised by a bust of him standing behind it.

Our next stop was to view the Cathedral on the Spilled Blood. In 1881, Alexander II was killed when a nihilist threw a bomb into his carriage, and Alexander III, his heartbroken son, had a cathedral built on the spot.

Our next stop was to view the Cathedral on the Spilled Blood. In 1881, Alexander II was killed when a nihilist threw a bomb into his carriage, and Alexander III, his heartbroken son, had a cathedral built on the spot.

Passing back through town, I got this hasty shot of the Kazan Cathedral (left) and at our next stop this photo of St. Isaac's Cathedral (right).

Passing back through town, I got this hasty shot of the Kazan Cathedral (left) and at our next stop this photo of St. Isaac's Cathedral (right).

Given a few minutes to walk around the palace gardens (now a park, behind me as I photographed St. Isaac's), I got these shots of decorative flower beds, two of a long series.

Given a few minutes to walk around the palace gardens (now a park, behind me as I photographed St. Isaac's), I got these shots of decorative flower beds, two of a long series.

Every time we drove anywhere to or from the ship, we passed this intriguing structure, and I never got a chance to ask what the heck it was. I thought it must be some sort of weird nuclear power plant, being right behind the pair of smoke stacks as it was. When I got home to Tallahassee, I looked it up (by the simple expedient of Googling "flying saucer building st. petersburg russia) and learned that it is in fact the city's administrative center, "Nevskaya ratusha." It just happens to be lined up behind the smoke stacks so that it looks as though they're together.

Every time we drove anywhere to or from the ship, we passed this intriguing structure, and I never got a chance to ask what the heck it was. I thought it must be some sort of weird nuclear power plant, being right behind the pair of smoke stacks as it was. When I got home to Tallahassee, I looked it up (by the simple expedient of Googling "flying saucer building st. petersburg russia) and learned that it is in fact the city's administrative center, "Nevskaya ratusha." It just happens to be lined up behind the smoke stacks so that it looks as though they're together.

And the day wasn't over yet! On the river bank, just a few yards (as promised) from the ship, was a large square white tent, like the ones they set up for big weddings. In it was a stage, and we were signed up for the evenings performance of Cossack music and dance.

And the day wasn't over yet! On the river bank, just a few yards (as promised) from the ship, was a large square white tent, like the ones they set up for big weddings. In it was a stage, and we were signed up for the evenings performance of Cossack music and dance.

The troupe seemed to consist of about a dozen dancers and singers, plus four instrumental musicians. They went throught several costume changes, alternating dancing numbers with singing and instrumental numbers, waving swords, etc.

The troupe seemed to consist of about a dozen dancers and singers, plus four instrumental musicians. They went throught several costume changes, alternating dancing numbers with singing and instrumental numbers, waving swords, etc.

Midway through the performance, the singers were startled and chased off the stage by the arrival of a pair of bulkily fur-clad dwarves locked in a desperate wrestling match. They rolled and tumbled around the stage, pushing and shoving each other. At one they fell off the stage and wrestled back and forth in front of it and then up and down the center aisle, bashing into tourists sitting there and jostling their chairs.n They somehow managed to wrestle each other back up the steps to the stage where, in the end, they were of course revealed to be a single dancer bent double, with boots on his hands and feet and heads mounted on his back.

Midway through the performance, the singers were startled and chased off the stage by the arrival of a pair of bulkily fur-clad dwarves locked in a desperate wrestling match. They rolled and tumbled around the stage, pushing and shoving each other. At one they fell off the stage and wrestled back and forth in front of it and then up and down the center aisle, bashing into tourists sitting there and jostling their chairs.n They somehow managed to wrestle each other back up the steps to the stage where, in the end, they were of course revealed to be a single dancer bent double, with boots on his hands and feet and heads mounted on his back.

Once the wrestling-dwarf number was over, I leaned forward to the lady sitting in front of me, in the first row, who had been pretty soundly buffeted (laughing all the while), and reminded her of my answer when she had earlier asked me why we sat in the second row when the first was empty, and several seats in rather than on the center aisle—we are always guarding against audience participation!

Once the wrestling-dwarf number was over, I leaned forward to the lady sitting in front of me, in the first row, who had been pretty soundly buffeted (laughing all the while), and reminded her of my answer when she had earlier asked me why we sat in the second row when the first was empty, and several seats in rather than on the center aisle—we are always guarding against audience participation!