Wednesday, 20 June, Sidecar, Metallurgy, and the Violon d'Ingres

Written 11 July 2018

As I mentioned in "Planning Ahead," we signed up for a 90-minute motorcycle tour of the Butte aux Cailles ("Quail Butte" or "Quail Hill") in the 13th arrondissement, as well as a look at "les Frigos" ("The Fridges"), once the refrigerated warehouse space associated the the Bercy warehouse district, now an arts incubator.

Wednesday was the day, but during breakfast, the Retro Tours office called to say they had a technical problem with one of the cycles, and could we possibly do our tour at noon rather than 11 a.m. I said sure and told David he could sleep in an extra hour. Then an hour later, they called to say the problem had been solved, and could we possibly do the tour at 11 a.m. as planned. I said sure, and David had to get up after all.

David still had serious misgivings about the whole process, but he gamely buckled on a helmet and came along. He was glad, though, that we weren't visiting the center of town; apparently at least 90% of those who sign up want to ride down the Champs Elysés, but we've been there and done that (though not on a motorcycle).

Here, at the curb, are our motorcycle and sidecar and in the photo at the right, our driver, Charlie. I sat in the sidecar, and David said behind Charlie, holding on to the little ring you can see right in front of the pillion seat. The rubberized fabric you can see draped over the windshield of the sidecar could be zipped over the rider's legs in inclement weather, but in our case, we just pulled it out so I could get my feet in (plenty of room for my purse down by my feet) and then stuffed it under the dashboard.

Here, at the curb, are our motorcycle and sidecar and in the photo at the right, our driver, Charlie. I sat in the sidecar, and David said behind Charlie, holding on to the little ring you can see right in front of the pillion seat. The rubberized fabric you can see draped over the windshield of the sidecar could be zipped over the rider's legs in inclement weather, but in our case, we just pulled it out so I could get my feet in (plenty of room for my purse down by my feet) and then stuffed it under the dashboard.

Charlie also professed himself glad that this wouldn't just be another trip down the Champs Elysés. He was proud to be showing us instead the neighborhood where he lives, which is, in his opinion (and his words), the coolest in Paris. He strapped us into helmets (no bluetooth; he just yelled his commentary), and off we went.

I'm afraid my photos from the motorcycle are pretty random, and I don't even know what some of them are. I just blasted away whenever I saw something interesting.

I'm afraid my photos from the motorcycle are pretty random, and I don't even know what some of them are. I just blasted away whenever I saw something interesting.

Here, still on our way to our target neighborhood, is a very shiny building (offices, I think, and some apartments on top) and, at the right, the the Institut du Monde Arabe. That's one item that's still on our to-do list; we've never visited it.

Once we were down in the 13th arrondissement, Charlie took us along the rue Tolbiac, once the epicenter of Chinatown (pronounced "CHEE-nah-toon" in French). I vividly remember a trip Françoise and I took down there to look at Tang Frères, a huge Chinese supermarket. We spent most of the afternoon studying their holdings and reading labels (Françoise's then husband Richard joked that they had to close for two days after we left, to put everything back in place.) Charlie told us it's still called Chinatown, but the population is now mostly vietnamese and Thai.

In left-bank area just across the river from Bercy, the architecture has gotten very modern (and "cool" according to Charlie). The building at the left here, the one with the network of metal "twigs" covering its windows (apartments, I think), was unmistakable and served as a useful landmark as we crisscrossed the neighborhood.

In left-bank area just across the river from Bercy, the architecture has gotten very modern (and "cool" according to Charlie). The building at the left here, the one with the network of metal "twigs" covering its windows (apartments, I think), was unmistakable and served as a useful landmark as we crisscrossed the neighborhood.

The "frigos" consists of more than one building, but here are two views of the largest. It still looks derelict, its status as arts incubator betrayed only by some wonderfully clever graffiti on the outside walls and the gaily decorated space in the right-hand photo—way back there in the angle of the building, behind the iron fence in the foreground—once a loading dock, now a patio with colorfully painted walls, tables, chairs, and café umbrellas. The banner hung on the wall above it reads "Office of the Mayor of Paris, 19 rue des Frigos, site of creation and production" and features, in the upper right-hand corner, a drawing of a guy carrying a block of ice on his shoulder, gripped in a pair of ice tongs.

The "frigos" consists of more than one building, but here are two views of the largest. It still looks derelict, its status as arts incubator betrayed only by some wonderfully clever graffiti on the outside walls and the gaily decorated space in the right-hand photo—way back there in the angle of the building, behind the iron fence in the foreground—once a loading dock, now a patio with colorfully painted walls, tables, chairs, and café umbrellas. The banner hung on the wall above it reads "Office of the Mayor of Paris, 19 rue des Frigos, site of creation and production" and features, in the upper right-hand corner, a drawing of a guy carrying a block of ice on his shoulder, gripped in a pair of ice tongs.

The wall in the left-hand photo is the one you'd see if you went around the building to the right. I wish the dragon whose mouth is formed by one of the windows showed up better. The mouth is the window on a line between Charlie's elbow and the blue light flare just below the eves.

In the older parts of the neighborhood, we saw charming nooks and crannies and architectural oddities, like this extremely narrow house.

In the older parts of the neighborhood, we saw charming nooks and crannies and architectural oddities, like this extremely narrow house.

It's also a particularly rich area for street art. I especially liked this beast of some sort, clutching a food item, made entirely of scrap materials rivetted together and nailed to a wall. If you can't at first see the animal, start with its curly blue tail, then look for the whiskers. Above those, you can see a nose, two eyes, and two ears. The upper part of the light-green portion of the diagonal food item is flanked by two sets of black clutching fingers. Wish we'd had more chance to study it.

We caught glimpses of many, many wonderful murals that I couldn't get photos of. For an article featuring photos of many of them, go to http://www.secretsofparis.com/heathers-secret-blog/more-murals-in-the-best-street-art-district-in-paris.html

The neighborhood church of La Butte Aux Cailles is Ste. Anne's on rue Tolbiac.

The neighborhood church of La Butte Aux Cailles is Ste. Anne's on rue Tolbiac.

At the right here is one of the wonderful little miniature city buses they use in the few parts of Paris where the streets are too narrow and winding for regular ones. One of the routes is here on the Butte aux Cailles; another is "Montmatrobus," which we've ridden up and over the Butte de Montmartre (on a tiny bus just like this one. I know of at least two other little short circular routes like these (the Batignolles-Bichet route and the Charonne route), but I don't know whether they also use the miniature buses

A place Charlie was particularly proud of was "Station F," which claims to be the world's largest business incubator and start-up campus. Like the Musée d'Orsay, it started life as a vast railway station (the one serving Les Frigos, in fact) and has now been extensively remodeled and is now ultramodern inside (compare the dilapidated state of Les Frigos—who makes more money, business incubators or arts incubators?). What you see here (on the left) is just one end of the long, long line of arched bays.

A place Charlie was particularly proud of was "Station F," which claims to be the world's largest business incubator and start-up campus. Like the Musée d'Orsay, it started life as a vast railway station (the one serving Les Frigos, in fact) and has now been extensively remodeled and is now ultramodern inside (compare the dilapidated state of Les Frigos—who makes more money, business incubators or arts incubators?). What you see here (on the left) is just one end of the long, long line of arched bays.

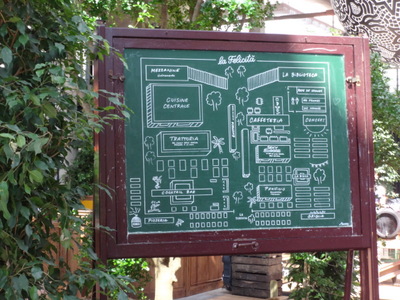

The last few bays at this end house what Charlie assured us was the largest restaurant in the world. It seats 1000. We weren't able to go in, as they were closed for the interval between lunch and dinner and hadn't yet reopened, but we peered in the door in time to see the staff do their preopening huddle and ritual moral-building shout. At the right is what we could see from our position. The blackboard sandwich sign behind the two staffers in the foreground lists the risotto of the day (Mangia Milanese) and the sweet flavor of the day (chocolate).

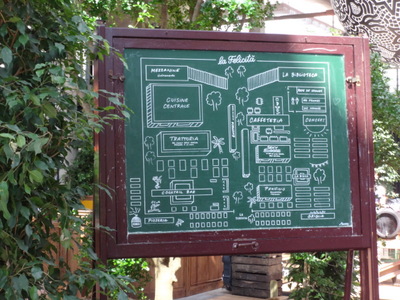

At the left here is a (fake) chalkboard showing a map of the place, so that diners know which way to go to get to the pizza line, the pasta area, the bakery, the beer pavilion, the the entertainment amphitheatre, "Sexy Burger," the "Cafeteria," the "Trattoria," the wine bar, etc. Yes, it's Italian food, but the menu didn't look very long for any of the areas.

At the left here is a (fake) chalkboard showing a map of the place, so that diners know which way to go to get to the pizza line, the pasta area, the bakery, the beer pavilion, the the entertainment amphitheatre, "Sexy Burger," the "Cafeteria," the "Trattoria," the wine bar, etc. Yes, it's Italian food, but the menu didn't look very long for any of the areas.

At the right is what we could see of the (very, very well-stocked) bar.

Here's some street art I did manage to photograph, because we stopped nearby. At the left is a scene from Tintin, and at the right a puzzling mural by an artist whose work I saw all over town.

Here's some street art I did manage to photograph, because we stopped nearby. At the left is a scene from Tintin, and at the right a puzzling mural by an artist whose work I saw all over town.

It always features mug shots of the same guy (the artist, presumably) made up in different ways as well as all sorts of variations on wanted posters, some featuring the mug shots and others painted, like these. Not sure what he's driving at, but he's very persistent and peripatetic.

At a couple of points along the way, Charlie stopped to take the obligatory photos of us on the bike . . .

At a couple of points along the way, Charlie stopped to take the obligatory photos of us on the bike . . .

Finally, by prearrangement, when our time was up, Charlie drove us up the Avenue Auguste Blanqui (recognizable by the elevated subway line running down its center) almost to the Place d'Italie, made sure we knew where we were, and dropped us off at a little restaurant he recommended, La Butte aux Piafs (Sparrow Butte or Sparrow Hill).

Finally, by prearrangement, when our time was up, Charlie drove us up the Avenue Auguste Blanqui (recognizable by the elevated subway line running down its center) almost to the Place d'Italie, made sure we knew where we were, and dropped us off at a little restaurant he recommended, La Butte aux Piafs (Sparrow Butte or Sparrow Hill).

Coincidentally, we were within a block of a Mercure Hotel where we once stayed for a few days. (I was very impressed with their soundproofing; I didn't realize an early morning market, complete with Dixieland band, was going on just below our windows until I opened one to see what the temperature was like.) The restaurant also rang a vague bell—we may have eaten lunch there before (and before my blogging days; I'll have to look it up in my handwritten diaries, as time permits).

Here are our lunches, and I'm embarrassed to say that neither of us can (a) remember what David ordered, (b) identify it from the photo, or (c) figure it out from the online menu. It must have been a special of the day; to me it looks like salmon tartare with fromage blanc on top, but who knows?

Here are our lunches, and I'm embarrassed to say that neither of us can (a) remember what David ordered, (b) identify it from the photo, or (c) figure it out from the online menu. It must have been a special of the day; to me it looks like salmon tartare with fromage blanc on top, but who knows?

Mine, on the other hand, is a "Dehli Burger," described on the menu as (in my translation) "sesame-seed bun, 200 g of degreased and seasoned chopped leg of lamb, curry sauce, tomato, red onion, toasted eggplant, and a little cup of mango chutney." The mango chutney was nowhere in evidence, but the burger was quite good. Gooey and dripping, though. After a couple of bites, I gave up and ate it with knife and fork. Both our lunches came with "potatoes," listed just like that on the menu, in English. Apparently that's what chunks (as opposed to fingers) of fried potatoes are called there.

A fun feature of the place was that each menu cover was handcrafted from an old 45-rpm record cover; they were all different.

Written 24 July 2018

Having finished our lunch, we found ourselves with the afternoon before us, so I talked David into visiting something I'd always wanted to see—the Paris Mint. In the nearby Place d'Italie, We caught the #7 metro line, which whisked us to Pont Neuf, just across the river from our destination. At the left here is the famous Samaritaine department store. While it's façade is being cleaned or renovated or some such, it is covered by this handsome drawing of itself with a cheerful shopper in a pink polka-dot skirt frolicking across it the front and a handsome couple lunching in its tearoom on the side.

Having finished our lunch, we found ourselves with the afternoon before us, so I talked David into visiting something I'd always wanted to see—the Paris Mint. In the nearby Place d'Italie, We caught the #7 metro line, which whisked us to Pont Neuf, just across the river from our destination. At the left here is the famous Samaritaine department store. While it's façade is being cleaned or renovated or some such, it is covered by this handsome drawing of itself with a cheerful shopper in a pink polka-dot skirt frolicking across it the front and a handsome couple lunching in its tearoom on the side.

Once we'd strolled across the Pont Neuf to the left bank, we were greeted in the courtyard of the mint by this magnificent stainless-steel tree, the leaves of which are milk pails, buckets, pots, pans, and cooking utensils. It's not part of the mint's usual displays but part of a temporary exhibition of art by Subodh Gupta.

David had been pretty skeptical, wondering what there could be to see at a mint, but he had to admit that it all turned out to be fascinating and informative. I show only a few representative items here. The path through the museum starts by explaining that the mint makes many items in addition to the everyday coins of commerce. Its principal other products are decorative metal castings, medals (both military and commemorative), and metal figurines.

David had been pretty skeptical, wondering what there could be to see at a mint, but he had to admit that it all turned out to be fascinating and informative. I show only a few representative items here. The path through the museum starts by explaining that the mint makes many items in addition to the everyday coins of commerce. Its principal other products are decorative metal castings, medals (both military and commemorative), and metal figurines.

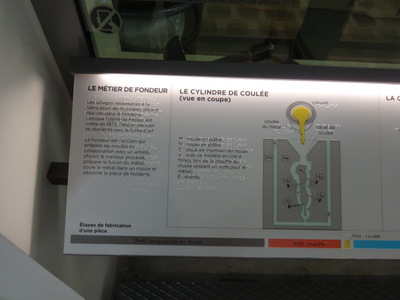

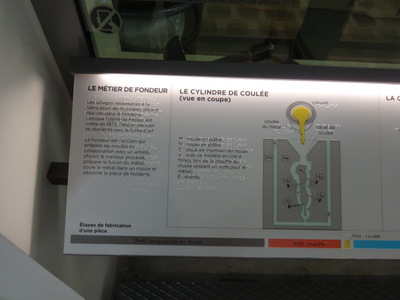

The panel at the left here explains what a "fondeur" (a worker in cast metal) does. In addition to the drawings on the panels, which diagram how the casting process works, we could look through large glass windows in the walls above the panels into the actual space where the work was done. The content of each panel was also cast in Braille, superimposed right on the printed words.

The next section was a collection of display cases, each dedicated to a different elemental metal or alloy. Only those metals useful in the sorts of things the mint does were included, but the displays were extremely information-rich. Each one gave the history of human use of the metal, as well as its characteristics, modern uses, and value as an ingredient in alloys. The one at the right here is for copper, the first metal mastered by humans. On the slim pedestals are various forms of copper ore as they appear in nature—information panels explain the order in which they were discovered and in which metallurgists figured out how to extract the metal. On the walls and floor are ancient and modern coins that incorporate copper, and the bright round objects covering part of the floor are copper ingots, which are roughly spherical and maybe the size of golf balls.

Similar cases and information panels covered lead, tin, zinc, nickel, aluminum, silver, chrome, iron, gold, titanium, and platinum as well as alloys like pewter, brass, bronze, and steel. I was reminded of two vocabulary items I never seem to remember: "laiton," which is brass (zinc and copper), and "bronze," which is bronze (tin and copper).

One long hallway was lined with panels illustrating the time line of the development of metallurgy and highlighting key dates and photos of important figures in the field.

One long hallway was lined with panels illustrating the time line of the development of metallurgy and highlighting key dates and photos of important figures in the field.

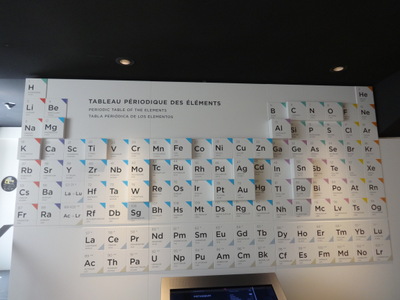

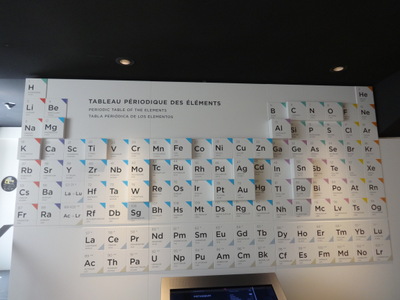

On the periodic table at the left (only one of several illustrating different features of elements), elements are elevated in proportion to their metallurgical importance/volume of use. Explanatory panels also explained the uses of nonmetallic elements important to metallurgical processes, like carbon and oxygen.

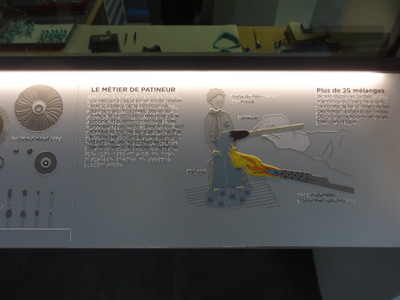

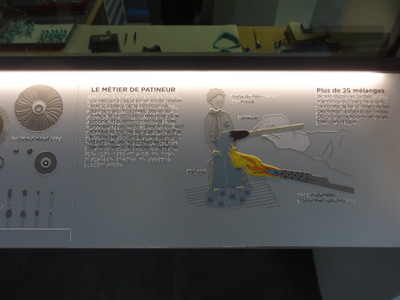

At the right is a panel explaining what a "patineur" does. (Here, you can reasily see the superimposed Braille. Each "metier" or "occupation" employed by the mint has its own panel, explaining what it entails, what tools it uses, and what its place is in the production of metal objects). The example shown is a figurine of le Petit Prince (from the book by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry). Once such a figurine has been cast (by the fondeur), it goes to the "ciseleur," who details it, filing off flash from the mold, inspecting for flaws, engraving any detail to fine to be cast, then finally to the patineur, who works with a brush in one hand and a small flame-thrower in the other. After polishing the surface with wire brushes, he brushes chemicals (the mint uses 25 different ones, mostly metal salts) onto the surface and melts them into place with the flame. No one was working in the shop behind the panel (and we were asked from the outset not to photograph mint employees anyway), but we watched a video of the process. What I couldn't understand is how the patineur avoids burning the bristles off his brush as he works—he seemed to be running the flame over it every few seconds!

On the counter in the empty shop was a tray of rows of little light-blue figurines of Astérix (a single ones stands on the sill just inside the window, to the left of the horse's head).

On the counter in the empty shop was a tray of rows of little light-blue figurines of Astérix (a single ones stands on the sill just inside the window, to the left of the horse's head).

At the right is another empty workshop, for a "ciseleur," I think.

Just as we finished our run through that section of the museum and reached a very large room displaying hundreds of commemorative medals and other objects, we were invited by a docent to

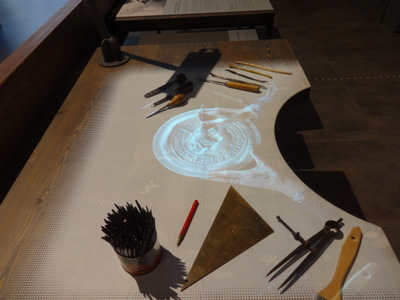

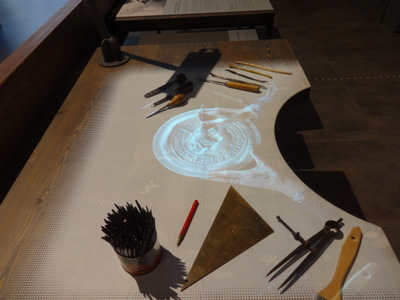

assemble for a live demonstration of engraving. The photo at the left shows a real engraver's desk, but while it is unoccupied, they project an image onto it of the engraver's hands as she works on the die for a medal.

Just as we finished our run through that section of the museum and reached a very large room displaying hundreds of commemorative medals and other objects, we were invited by a docent to

assemble for a live demonstration of engraving. The photo at the left shows a real engraver's desk, but while it is unoccupied, they project an image onto it of the engraver's hands as she works on the die for a medal.

Medals, medallions, and coins are not cast, of course; they are "struck." The engraver's job is to carve a "negative" of the desired image into a solid block of metal, which is then used to stamp that image onto the lump of metal that will bear the "positive" image and become the medal or coin. She uses a whole array of little chisles of different shapes, which she taps with a hammer as she guides them across the surface. To check the image as she goes, she uses a wooden pestle with a thick lump of beeswax on the end. She dusts the wax with a little cornstarch, so it won't stick, places it on the spot she wants to check, whacks the top of the handle smartly with her hammer. The image is transferred, in perfect detail, to the wax.

At the right is the negative image (a woman's head in profile, from a reddish drawing at the upper right) we saw the engraver work on (photographed before she sat down, since I wasn't supposed to photograph her). It is about the size of a salad plate, so she can work in great detail, especially on the hair.

Once the negative image is complete, it is placed on a crank-operated mechanical device (the size of a Volkswagen) called a "reducing wheel" (actually a 3D pantograph) that carves an exact replica of it, in a harder metal, but at a smaller size (say, a couple of inches across). That replica in a harder metal is actually the die used, after addition of some little codes around the rim (to indicate the date, which mint made it, etc.) to stamp the coin or medal. Stamping metal into shape as though it were wax is hard work, so the die doesn't last long—certainly not long enough to make, e.g., a year's worth of pennies. Fortunately, the reducing wheel can easily produce a replacement from the original hand-carved engraving, which remains unchanged.

These two slides illustrate the steps involved in making the medal worn by members of the Légion d'Honneur, including increasingly elaborate engraving, cutting, attachment of hanging ring, enamelling of the frame and inserts, and final assembly.

These two slides illustrate the steps involved in making the medal worn by members of the Légion d'Honneur, including increasingly elaborate engraving, cutting, attachment of hanging ring, enamelling of the frame and inserts, and final assembly.

The rest of the barn-sized room was full of display cases setting out the many coins and medals produced at the mint, as well as displays of the processes involved in producing, e.g., coins whose two faces are made of different metals, "sandwich" coins (like the American quarter), and coins whose rims and centers are made of different metals (like the one- and two-Euro coins).

By the time we finished with the permanent exhibitions, David's feet had had it, but I still wanted to look at the Gupta stuff. On our way to the indoor portion of his exhibition, we passed this life size cast-aluminum replica of an ambassador's car in an inner courtyard (not the same courtyard as the tree). It's entitled "Doot," which means "ambassador" in "Indian" (they didn't specify which Indian language).

By the time we finished with the permanent exhibitions, David's feet had had it, but I still wanted to look at the Gupta stuff. On our way to the indoor portion of his exhibition, we passed this life size cast-aluminum replica of an ambassador's car in an inner courtyard (not the same courtyard as the tree). It's entitled "Doot," which means "ambassador" in "Indian" (they didn't specify which Indian language).

Back inside, David settled on a bench while I did a quick run through the exhibition. He seems to make two kinds of things—all-metal replicas of nonmetal objects and assemblages of cooking gear. The column in the right-hand photo is both: a replica of a column made of cylindrical stainless steel cannisters. It was one of several columns made of different assemblages. The group of columns was entitled "Adda," which appearently means "forum" or "place of cultural assembly and discussion."

At the left here is my favorite after the tree, entitled "Insatiable God." As you can tell by the size of the woman standing near it, it was very large. At the right is a close-up of one section of it, showing the assortment of cannisters, buckets, ladels, metal dishes, etc. that make it up. I even saw a food mill in there.

At the left here is my favorite after the tree, entitled "Insatiable God." As you can tell by the size of the woman standing near it, it was very large. At the right is a close-up of one section of it, showing the assortment of cannisters, buckets, ladels, metal dishes, etc. that make it up. I even saw a food mill in there.

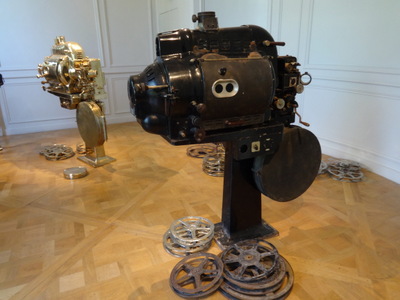

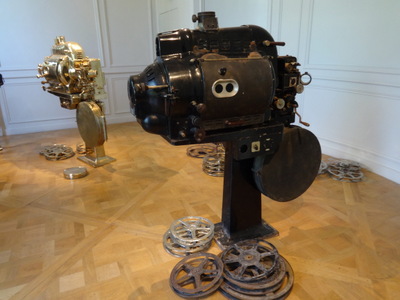

At the left here is one of his replicas. In the foreground is a real, antique movie projector. At the rear is his brass replica of it. Another example (not pictured here) was an old-fashioned toilet with the overhead tank and pull chain, faithfully replicated in brass, pipes and all. A third was two complete brass bicycles hung with milk pails, labeled "Two Cows."

At the left here is one of his replicas. In the foreground is a real, antique movie projector. At the rear is his brass replica of it. Another example (not pictured here) was an old-fashioned toilet with the overhead tank and pull chain, faithfully replicated in brass, pipes and all. A third was two complete brass bicycles hung with milk pails, labeled "Two Cows."

The installation at the right consists of many, many Indian-style stackable lunch pails (in brass, aluminum, and stainless steel), set on a rectangular, concentric set of the metal conveyor belts used in some sushi restaurants. All the belts were in motion, some clockwise, some counterclockwise.

A few objects were out of his two main genres: A dugout canoe standing up at a 45-degree angle and filled to overflowing with terracotta water bottles. A wooden table scattered with flour and bearing a lump of bread dough (supposedly consisting of a wooden table, flour, and painted bronze, so I guess the dough was actually made of bronze). A room lined with large, not very flat metal mirrors, as in a fun-house, except that periodically, the sheets of metal vibrated and shook, producing the sound of thunder.

After our usual afternoon rest back at the apartment, dinner was at old friend Le Violon d'Ingres on rue Saint Dominique, so our faithful metro line #8 was once more the obvious choice.

After our usual afternoon rest back at the apartment, dinner was at old friend Le Violon d'Ingres on rue Saint Dominique, so our faithful metro line #8 was once more the obvious choice.

Gone are the radishes and butter of yesteryear; the first amuse-bouche was sticks of crisp puff pastry and roasted almonds. The second was tiny glasses of jelled tomato soup.

The first course of our seven-course tasting menu, shown here at the left, was cold cream of pea soup with a dollop of sheep's-milk curd, decorated with pea sprouts and radish slices.

Second course: a chilled, jellied terrine of cooked turbot, smoked eel, and foie gras, accompanied by eggplant caviare and horseradish. The green parts were cooked leek. Note the bronze Oxalis leaf; everyone was garnishing with Oxalis this year.

Third course, duck foie gras sautéed in a crust of dry pain d'épice crumbs, accompanied by a new carrot caramelized with acacia honey. (Actually, all the foie gras we were served this trip was explicitly listed as duck foie gras. Goose foie gras has always been costlier, but now I hear rumors that the rules governing the fattening of geese may have changed again, further limiting the suppy. Duck foie gras may be the direction of the future.)

Third course, duck foie gras sautéed in a crust of dry pain d'épice crumbs, accompanied by a new carrot caramelized with acacia honey. (Actually, all the foie gras we were served this trip was explicitly listed as duck foie gras. Goose foie gras has always been costlier, but now I hear rumors that the rules governing the fattening of geese may have changed again, further limiting the suppy. Duck foie gras may be the direction of the future.)

Fourth course: Filet of bar (Dicentrarchus labrax, European sea bass) sautéed in an almond crust, with tangy lemon-caper sauce. It rested on a bed of baby spinach and was surrounded by, in addition to the capers, cracked roasted hazelnuts.

Fifth course, roasted farmer pigeon from the Landes (the marshy plains south of Bordeaux), roasted with gray shallots. It rested on a bed of baby fava beans cooked with bacon and was garnished with both nasturtium leaves and Oxalis. Yummy.

Fifth course, roasted farmer pigeon from the Landes (the marshy plains south of Bordeaux), roasted with gray shallots. It rested on a bed of baby fava beans cooked with bacon and was garnished with both nasturtium leaves and Oxalis. Yummy.

Sixth course: Mixed red berries "à l'orange," garnished with strawberry sorbet and crushed Jordan almonds.

Seventh course: "The notorious chocolate tart of Christian Constant." Constant is the owner of the restaurant and of several others in the neighborhood. It was excellent, but I couldn't eat the caramelized hazelnut balanced on top because it was covered with bits of gold foil glued on too securely to be removed.

Seventh course: "The notorious chocolate tart of Christian Constant." Constant is the owner of the restaurant and of several others in the neighborhood. It was excellent, but I couldn't eat the caramelized hazelnut balanced on top because it was covered with bits of gold foil glued on too securely to be removed.

Finally, the mignardises: miniature cannelé, which were uncharacteristically gummy in the center and chocolate truffles and tiny lemon-strawberry tarts, which I didn't try.

A fine dinner, and unmarred by priceless menus, napkins that the waiter wants to put in your lap for you, waiters who insist you tell them whether you liked every course (even when you've clearly eaten every bit and licked the plate), and other stupidities of overly formal dining.

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

Here, at the curb, are our motorcycle and sidecar and in the photo at the right, our driver, Charlie. I sat in the sidecar, and David said behind Charlie, holding on to the little ring you can see right in front of the pillion seat. The rubberized fabric you can see draped over the windshield of the sidecar could be zipped over the rider's legs in inclement weather, but in our case, we just pulled it out so I could get my feet in (plenty of room for my purse down by my feet) and then stuffed it under the dashboard.

Here, at the curb, are our motorcycle and sidecar and in the photo at the right, our driver, Charlie. I sat in the sidecar, and David said behind Charlie, holding on to the little ring you can see right in front of the pillion seat. The rubberized fabric you can see draped over the windshield of the sidecar could be zipped over the rider's legs in inclement weather, but in our case, we just pulled it out so I could get my feet in (plenty of room for my purse down by my feet) and then stuffed it under the dashboard.

I'm afraid my photos from the motorcycle are pretty random, and I don't even know what some of them are. I just blasted away whenever I saw something interesting.

I'm afraid my photos from the motorcycle are pretty random, and I don't even know what some of them are. I just blasted away whenever I saw something interesting.

In left-bank area just across the river from Bercy, the architecture has gotten very modern (and "cool" according to Charlie). The building at the left here, the one with the network of metal "twigs" covering its windows (apartments, I think), was unmistakable and served as a useful landmark as we crisscrossed the neighborhood.

In left-bank area just across the river from Bercy, the architecture has gotten very modern (and "cool" according to Charlie). The building at the left here, the one with the network of metal "twigs" covering its windows (apartments, I think), was unmistakable and served as a useful landmark as we crisscrossed the neighborhood.

The "frigos" consists of more than one building, but here are two views of the largest. It still looks derelict, its status as arts incubator betrayed only by some wonderfully clever graffiti on the outside walls and the gaily decorated space in the right-hand photo—way back there in the angle of the building, behind the iron fence in the foreground—once a loading dock, now a patio with colorfully painted walls, tables, chairs, and café umbrellas. The banner hung on the wall above it reads "Office of the Mayor of Paris, 19 rue des Frigos, site of creation and production" and features, in the upper right-hand corner, a drawing of a guy carrying a block of ice on his shoulder, gripped in a pair of ice tongs.

The "frigos" consists of more than one building, but here are two views of the largest. It still looks derelict, its status as arts incubator betrayed only by some wonderfully clever graffiti on the outside walls and the gaily decorated space in the right-hand photo—way back there in the angle of the building, behind the iron fence in the foreground—once a loading dock, now a patio with colorfully painted walls, tables, chairs, and café umbrellas. The banner hung on the wall above it reads "Office of the Mayor of Paris, 19 rue des Frigos, site of creation and production" and features, in the upper right-hand corner, a drawing of a guy carrying a block of ice on his shoulder, gripped in a pair of ice tongs.

In the older parts of the neighborhood, we saw charming nooks and crannies and architectural oddities, like this extremely narrow house.

In the older parts of the neighborhood, we saw charming nooks and crannies and architectural oddities, like this extremely narrow house.

The neighborhood church of La Butte Aux Cailles is Ste. Anne's on rue Tolbiac.

The neighborhood church of La Butte Aux Cailles is Ste. Anne's on rue Tolbiac.

A place Charlie was particularly proud of was "Station F," which claims to be the world's largest business incubator and start-up campus. Like the Musée d'Orsay, it started life as a vast railway station (the one serving Les Frigos, in fact) and has now been extensively remodeled and is now ultramodern inside (compare the dilapidated state of Les Frigos—who makes more money, business incubators or arts incubators?). What you see here (on the left) is just one end of the long, long line of arched bays.

A place Charlie was particularly proud of was "Station F," which claims to be the world's largest business incubator and start-up campus. Like the Musée d'Orsay, it started life as a vast railway station (the one serving Les Frigos, in fact) and has now been extensively remodeled and is now ultramodern inside (compare the dilapidated state of Les Frigos—who makes more money, business incubators or arts incubators?). What you see here (on the left) is just one end of the long, long line of arched bays.

At the left here is a (fake) chalkboard showing a map of the place, so that diners know which way to go to get to the pizza line, the pasta area, the bakery, the beer pavilion, the the entertainment amphitheatre, "Sexy Burger," the "Cafeteria," the "Trattoria," the wine bar, etc. Yes, it's Italian food, but the menu didn't look very long for any of the areas.

At the left here is a (fake) chalkboard showing a map of the place, so that diners know which way to go to get to the pizza line, the pasta area, the bakery, the beer pavilion, the the entertainment amphitheatre, "Sexy Burger," the "Cafeteria," the "Trattoria," the wine bar, etc. Yes, it's Italian food, but the menu didn't look very long for any of the areas.

Here's some street art I did manage to photograph, because we stopped nearby. At the left is a scene from Tintin, and at the right a puzzling mural by an artist whose work I saw all over town.

Here's some street art I did manage to photograph, because we stopped nearby. At the left is a scene from Tintin, and at the right a puzzling mural by an artist whose work I saw all over town.

At a couple of points along the way, Charlie stopped to take the obligatory photos of us on the bike . . .

At a couple of points along the way, Charlie stopped to take the obligatory photos of us on the bike . . .

Finally, by prearrangement, when our time was up, Charlie drove us up the Avenue Auguste Blanqui (recognizable by the elevated subway line running down its center) almost to the Place d'Italie, made sure we knew where we were, and dropped us off at a little restaurant he recommended, La Butte aux Piafs (Sparrow Butte or Sparrow Hill).

Finally, by prearrangement, when our time was up, Charlie drove us up the Avenue Auguste Blanqui (recognizable by the elevated subway line running down its center) almost to the Place d'Italie, made sure we knew where we were, and dropped us off at a little restaurant he recommended, La Butte aux Piafs (Sparrow Butte or Sparrow Hill).

Here are our lunches, and I'm embarrassed to say that neither of us can (a) remember what David ordered, (b) identify it from the photo, or (c) figure it out from the online menu. It must have been a special of the day; to me it looks like salmon tartare with fromage blanc on top, but who knows?

Here are our lunches, and I'm embarrassed to say that neither of us can (a) remember what David ordered, (b) identify it from the photo, or (c) figure it out from the online menu. It must have been a special of the day; to me it looks like salmon tartare with fromage blanc on top, but who knows?

Having finished our lunch, we found ourselves with the afternoon before us, so I talked David into visiting something I'd always wanted to see—the Paris Mint. In the nearby Place d'Italie, We caught the #7 metro line, which whisked us to Pont Neuf, just across the river from our destination. At the left here is the famous Samaritaine department store. While it's façade is being cleaned or renovated or some such, it is covered by this handsome drawing of itself with a cheerful shopper in a pink polka-dot skirt frolicking across it the front and a handsome couple lunching in its tearoom on the side.

Having finished our lunch, we found ourselves with the afternoon before us, so I talked David into visiting something I'd always wanted to see—the Paris Mint. In the nearby Place d'Italie, We caught the #7 metro line, which whisked us to Pont Neuf, just across the river from our destination. At the left here is the famous Samaritaine department store. While it's façade is being cleaned or renovated or some such, it is covered by this handsome drawing of itself with a cheerful shopper in a pink polka-dot skirt frolicking across it the front and a handsome couple lunching in its tearoom on the side.

David had been pretty skeptical, wondering what there could be to see at a mint, but he had to admit that it all turned out to be fascinating and informative. I show only a few representative items here. The path through the museum starts by explaining that the mint makes many items in addition to the everyday coins of commerce. Its principal other products are decorative metal castings, medals (both military and commemorative), and metal figurines.

David had been pretty skeptical, wondering what there could be to see at a mint, but he had to admit that it all turned out to be fascinating and informative. I show only a few representative items here. The path through the museum starts by explaining that the mint makes many items in addition to the everyday coins of commerce. Its principal other products are decorative metal castings, medals (both military and commemorative), and metal figurines.

One long hallway was lined with panels illustrating the time line of the development of metallurgy and highlighting key dates and photos of important figures in the field.

One long hallway was lined with panels illustrating the time line of the development of metallurgy and highlighting key dates and photos of important figures in the field.

On the counter in the empty shop was a tray of rows of little light-blue figurines of Astérix (a single ones stands on the sill just inside the window, to the left of the horse's head).

On the counter in the empty shop was a tray of rows of little light-blue figurines of Astérix (a single ones stands on the sill just inside the window, to the left of the horse's head).

Just as we finished our run through that section of the museum and reached a very large room displaying hundreds of commemorative medals and other objects, we were invited by a docent to

assemble for a live demonstration of engraving. The photo at the left shows a real engraver's desk, but while it is unoccupied, they project an image onto it of the engraver's hands as she works on the die for a medal.

Just as we finished our run through that section of the museum and reached a very large room displaying hundreds of commemorative medals and other objects, we were invited by a docent to

assemble for a live demonstration of engraving. The photo at the left shows a real engraver's desk, but while it is unoccupied, they project an image onto it of the engraver's hands as she works on the die for a medal.

These two slides illustrate the steps involved in making the medal worn by members of the Légion d'Honneur, including increasingly elaborate engraving, cutting, attachment of hanging ring, enamelling of the frame and inserts, and final assembly.

These two slides illustrate the steps involved in making the medal worn by members of the Légion d'Honneur, including increasingly elaborate engraving, cutting, attachment of hanging ring, enamelling of the frame and inserts, and final assembly.

By the time we finished with the permanent exhibitions, David's feet had had it, but I still wanted to look at the Gupta stuff. On our way to the indoor portion of his exhibition, we passed this life size cast-aluminum replica of an ambassador's car in an inner courtyard (not the same courtyard as the tree). It's entitled "Doot," which means "ambassador" in "Indian" (they didn't specify which Indian language).

By the time we finished with the permanent exhibitions, David's feet had had it, but I still wanted to look at the Gupta stuff. On our way to the indoor portion of his exhibition, we passed this life size cast-aluminum replica of an ambassador's car in an inner courtyard (not the same courtyard as the tree). It's entitled "Doot," which means "ambassador" in "Indian" (they didn't specify which Indian language).

At the left here is my favorite after the tree, entitled "Insatiable God." As you can tell by the size of the woman standing near it, it was very large. At the right is a close-up of one section of it, showing the assortment of cannisters, buckets, ladels, metal dishes, etc. that make it up. I even saw a food mill in there.

At the left here is my favorite after the tree, entitled "Insatiable God." As you can tell by the size of the woman standing near it, it was very large. At the right is a close-up of one section of it, showing the assortment of cannisters, buckets, ladels, metal dishes, etc. that make it up. I even saw a food mill in there.

At the left here is one of his replicas. In the foreground is a real, antique movie projector. At the rear is his brass replica of it. Another example (not pictured here) was an old-fashioned toilet with the overhead tank and pull chain, faithfully replicated in brass, pipes and all. A third was two complete brass bicycles hung with milk pails, labeled "Two Cows."

At the left here is one of his replicas. In the foreground is a real, antique movie projector. At the rear is his brass replica of it. Another example (not pictured here) was an old-fashioned toilet with the overhead tank and pull chain, faithfully replicated in brass, pipes and all. A third was two complete brass bicycles hung with milk pails, labeled "Two Cows."

After our usual afternoon rest back at the apartment, dinner was at old friend Le Violon d'Ingres on rue Saint Dominique, so our faithful metro line #8 was once more the obvious choice.

After our usual afternoon rest back at the apartment, dinner was at old friend Le Violon d'Ingres on rue Saint Dominique, so our faithful metro line #8 was once more the obvious choice.

Third course, duck foie gras sautéed in a crust of dry pain d'épice crumbs, accompanied by a new carrot caramelized with acacia honey. (Actually, all the foie gras we were served this trip was explicitly listed as duck foie gras. Goose foie gras has always been costlier, but now I hear rumors that the rules governing the fattening of geese may have changed again, further limiting the suppy. Duck foie gras may be the direction of the future.)

Third course, duck foie gras sautéed in a crust of dry pain d'épice crumbs, accompanied by a new carrot caramelized with acacia honey. (Actually, all the foie gras we were served this trip was explicitly listed as duck foie gras. Goose foie gras has always been costlier, but now I hear rumors that the rules governing the fattening of geese may have changed again, further limiting the suppy. Duck foie gras may be the direction of the future.)

Fifth course, roasted farmer pigeon from the Landes (the marshy plains south of Bordeaux), roasted with gray shallots. It rested on a bed of baby fava beans cooked with bacon and was garnished with both nasturtium leaves and Oxalis. Yummy.

Fifth course, roasted farmer pigeon from the Landes (the marshy plains south of Bordeaux), roasted with gray shallots. It rested on a bed of baby fava beans cooked with bacon and was garnished with both nasturtium leaves and Oxalis. Yummy.

Seventh course: "The notorious chocolate tart of Christian Constant." Constant is the owner of the restaurant and of several others in the neighborhood. It was excellent, but I couldn't eat the caramelized hazelnut balanced on top because it was covered with bits of gold foil glued on too securely to be removed.

Seventh course: "The notorious chocolate tart of Christian Constant." Constant is the owner of the restaurant and of several others in the neighborhood. It was excellent, but I couldn't eat the caramelized hazelnut balanced on top because it was covered with bits of gold foil glued on too securely to be removed.