Wednesday, 27 June, Science at last and the last big dinner

Written 2 August 2018

Time for another attempt to visit La Cité de la Science et de l'Industrie, where I still wanted to see the special exhibitions on special effects and cold.

After splitting the giant sugared brioche for breakfast, we set off once again for La Villette, and this time had no trouble getting in. I had even bought tickets on line and managed to get them onto my cell phone so they could be scanned at the door. Lesson for next time, though:L Some, but not all, on-line ticket sellers offer the option to send the tickets to your smart phone. For those that don't, because they assume you have a printer, it is a real pain to get those tickets onto your phone and then to find them again when you need them. For our next trip, I'm doing more advance research on prepurchased tickets and printing them out before I leave home. Those work like a charm. The ones bought at the last minute might have worked better if we'd been in a hotel, where I could have asked the office to print them for me or used the "business center" in the lobby.

After splitting the giant sugared brioche for breakfast, we set off once again for La Villette, and this time had no trouble getting in. I had even bought tickets on line and managed to get them onto my cell phone so they could be scanned at the door. Lesson for next time, though:L Some, but not all, on-line ticket sellers offer the option to send the tickets to your smart phone. For those that don't, because they assume you have a printer, it is a real pain to get those tickets onto your phone and then to find them again when you need them. For our next trip, I'm doing more advance research on prepurchased tickets and printing them out before I leave home. Those work like a charm. The ones bought at the last minute might have worked better if we'd been in a hotel, where I could have asked the office to print them for me or used the "business center" in the lobby.

We found the special-effects exhibition first, so we started there. It was Comprehensive, with a capital "C." It started with a list of all the techniques used, now and formerly, to produce special effects on film: stop motion (like claymation), puppets and animatronics, substitution splicing, visual effects (tinkering with the images in postproduction), scale models, chroma key compositing (green screen), matte/counter-matte, matte painting, rear projection, CGI, bullet time (as in The Matrix, where the camera appears to swing in a circle around the actors), and motion capture. Then is went into great detail about the making of a film in general (from script writing and location scouting through distribution; the giant flow chart filled a whole wall), who on the production team does what, and how and at what stages special effects are introduced. Then it stepped systematically through through all the techniques, explaining how each was carried out and in what situations each was preferred, cases in which film-makers might want to revert to "old-fashioned" techniques, etc. Unfortunately, it was singularly unphotogenic, because so much text was used (in three languages throughout), and a lot of the rest of the material was on film!

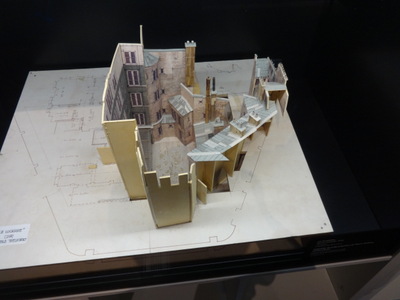

The model at the right here was, as I understand it, not actually used in the film but served as an aid to the film-maker in planning the action that took place in the area the model represented.

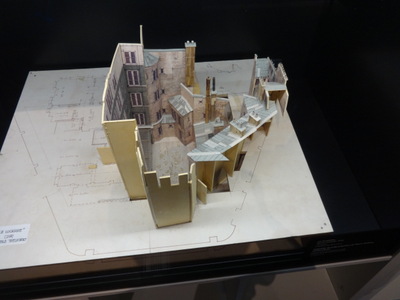

Here, at the left, is another planning model (for Roman Polanski's Le Locataire, called The Tenant in English). It rests on a floor plan of the entire castle of which it represents only a part.

Here, at the left, is another planning model (for Roman Polanski's Le Locataire, called The Tenant in English). It rests on a floor plan of the entire castle of which it represents only a part.

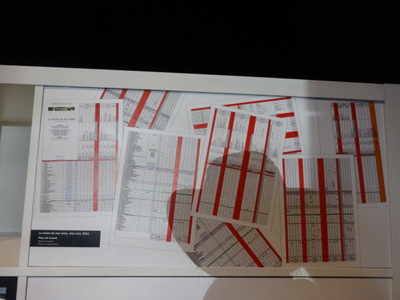

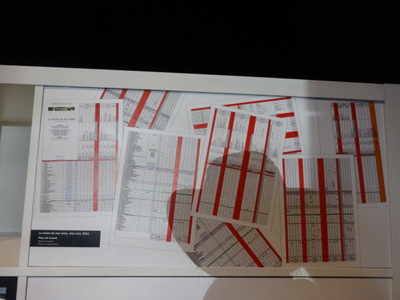

The pages on this bulletin board are part of the "work schedule" for Le Talent de mes Amis. It's made up for each film by the first assistant director to group scenes by location and to take into account all the constraints on all the participants' schedules, location availability, weather, what costumes and props are needed, any special effects that need to be incorporated and much more that I would never even have thought of. All this is presumably part of what they teach at the FSU Film School.

Here are a couple of animatronic gremlins from the movies of that name. The exhibition also went into great detail about make-up and prosthetics, using as one example the costuming from the Planet of the Apes movies, which also included motion capture—we saw films of Andy Serkis doing the motion-capture scenes as well as the movies scenes that resulted.

Here are a couple of animatronic gremlins from the movies of that name. The exhibition also went into great detail about make-up and prosthetics, using as one example the costuming from the Planet of the Apes movies, which also included motion capture—we saw films of Andy Serkis doing the motion-capture scenes as well as the movies scenes that resulted.

I really enjoyed some of the older films, some going all the way back to the time of the Lumière brothers. In particular, Georges Méliès, who had been a professional stage magician, took one look at this new medium of film and embraced it with both arms. In a silent black and white film of his called Le d&ecute;shabillage impossible (The impossible undressing), he used substitution splicing to film a man trying to undress for a good half hour. No matter now many clothes he takes off, he's wearing still others, and huge heaps of clothing pile up in the corners of the room as he tries to get them all off. At one point, in great frustration, he snatches off and throws away about 20 different hats in rapid succession, only to have a new one appear on his head before each old one is out of his hand. The effect is amazingly good considering the film was made in 1900!

Of course, we got to see ourselves in green-screen and with rear projection, and I ventured into the "no children allowed" room with all the really gruesome mutilation models and prosthetics. They even had a collection of particularly good matte paintings (the far distance that blends into the real scenery behind the actors when the scene is shot in a studio or something unwanted appears in the background outdoors).

The exhibition was so good, we spent almost all our time there, breaking in the middle for lunch.

We found lunch at "Le Rest'" on the lower level. David had beef tartare with fries, which was quite good. I had an only-okay salad nicoise, once again with olives of no particular character.

We found lunch at "Le Rest'" on the lower level. David had beef tartare with fries, which was quite good. I had an only-okay salad nicoise, once again with olives of no particular character.

For dessert, we split a panna cotta with mango coulis.

For dessert, we split a panna cotta with mango coulis.

Back upstairs, looking for the exhibition on cold, we came across the wonderful "Turbulent Fountain" that we had so admired on our last visit. On an inclined metal surface, a post with many spokes supports 12 conical buckets, each with a small hole in the bottom. Across the top, five small spigots dispense water continuously, a little faster than it can run out the bottom of the bucket under it. When a bucket at the top fills and gets heavy, its weight causes the post and its spokes to turn, bringing other buckets to pass under the spigots, while the first bucket loses weight as water drains out the hole in its bottom. If it was really full, it spun the wheel fairly fast, meaning that the new buckets passed quickly through the "spigot zone" and collected only a little water, so they don't propel the wheel so quickly, allowing the ones behind them to collect more water speeding things up again. But if the wheel is turning counterclockwise so slowly that a bucket has a chance to collect lots of water from the first spigot, before it has reached the top of the circle, its weight will stop the wheel and make it reverse to turn clockwise. And so it goes. The wheel speeds up, slows down, speeds up, reverses, stops, continues, reverses again ad infinitum in entirely unpredictable fashion. (The label says that no computer model can predict its behavior more than two minutes into the future.) I could watch it for hours. That's another installation I'd love to have in my house!

We also passed through the building's large central atrium, where I got shots from slightly above and slightly below a solar-powered airplane. "Solvay" is a Belgian company that presumably helped build it; along the tail it says "SolarImpulse across the U.S.A."

We also passed through the building's large central atrium, where I got shots from slightly above and slightly below a solar-powered airplane. "Solvay" is a Belgian company that presumably helped build it; along the tail it says "SolarImpulse across the U.S.A."

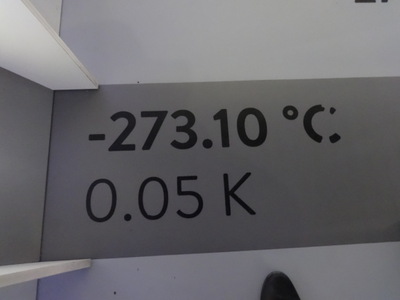

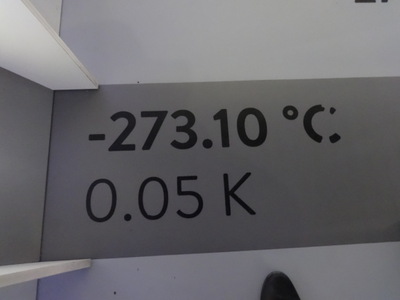

The entrance to the cold exhibit was through a winding path along a figurative gradient from 0°C to absolute zero. Every few steps, graphics and text would signal some some particularly significant temperature—lowest temperature in a home freezer, temperature of frozen carbon dioxide, temperature of frozen oxygen, etc. The last temperature at which anything was indicated was this one (left), 0.05°K, at which a small sign and photo indicated that tardigrades (commonly called water bears, at least among those who've ever heard of them) could survive for several hours. Tardigrades! Who knew?! Let's hear it for the meiofauna!

The entrance to the cold exhibit was through a winding path along a figurative gradient from 0°C to absolute zero. Every few steps, graphics and text would signal some some particularly significant temperature—lowest temperature in a home freezer, temperature of frozen carbon dioxide, temperature of frozen oxygen, etc. The last temperature at which anything was indicated was this one (left), 0.05°K, at which a small sign and photo indicated that tardigrades (commonly called water bears, at least among those who've ever heard of them) could survive for several hours. Tardigrades! Who knew?! Let's hear it for the meiofauna!

Since "cosmic background temperature" is almost 2.6°K, tardigrades could be hitchhiking around space on comets!

The exhibit seemed to be pitched at a younger age group. It mentioned things like mammoths frozen in glaciers, the history of refrigeration (from natural ice cut from rivers to artificial ice machines), use of tiny hidden tags in yogurt containers that track the cold chain through which yogurts pass during distribution (for quality control purposes), plants' different strategies for dealing with cold, and the difference between the French words "congélation" and "surgélation, which I had actually often wondered about. The former is just "freezing" and the second is "flash freezing" (or as the labels translated it, deep freezing, but the descriptions made clear they meant flash freezing).

Our feet wouldn't take much more, so we headed home to rest up before dinner. I highly recommend that museum, though. They have separate sections set aside for children of different age ranges, and you could spend days if you wanted to see everything. Qutie aside from the children's sections, the best science museum for grown-ups we know of.

Written 3 August 2018

For dinner, we went to Le Laurent, which is located in the Jardin des Champs l'Elysées (a park one block by two long blocks that parallels the Champs Elysées from the Place de la Concorde to the Rond Point. There we were, in a lovely walled, tree-shaded garden, just a block off the Champs Élysées and about a block and a half from the French presidential palace.

For dinner, we went to Le Laurent, which is located in the Jardin des Champs l'Elysées (a park one block by two long blocks that parallels the Champs Elysées from the Place de la Concorde to the Rond Point. There we were, in a lovely walled, tree-shaded garden, just a block off the Champs Élysées and about a block and a half from the French presidential palace.

The amuse-bouche was, for each of us, a crisp pastry tube filled with a smooth eggplant cream, a little circular slice of meat with olive tapenade on top, and a tiny tartlet filled with guacamole and garnished with a bit of smoked salmon. I ate David's meat slice, and he ate my guacamole.

Strangely, we were then served warm slices of toast. The waiter extended the basket and lifted the napkin, inviting us to take them with our fingers, which struck me as odd for a restaurant of this calibre, where even when they bring you a fresh napkin (should you, for example, drop yours on the floor), they hand it to you with tongs. A few minutes later, I saw toast being served to another table, this time with tongs, and a few minutes after that, regular small breads appeared and were served (with tongs) to everyone for the rest of the evening. My theory is that the baker ran late, and the small breads weren't ready by the time the waiters thought we should have bread, so they improvised and toasted slices of bread left from the lunch service. We probably got the junior-most waiter, who probably got smacked upside the head for not knowing enough to use tongs.

Strangely, we were then served warm slices of toast. The waiter extended the basket and lifted the napkin, inviting us to take them with our fingers, which struck me as odd for a restaurant of this calibre, where even when they bring you a fresh napkin (should you, for example, drop yours on the floor), they hand it to you with tongs. A few minutes later, I saw toast being served to another table, this time with tongs, and a few minutes after that, regular small breads appeared and were served (with tongs) to everyone for the rest of the evening. My theory is that the baker ran late, and the small breads weren't ready by the time the waiters thought we should have bread, so they improvised and toasted slices of bread left from the lunch service. We probably got the junior-most waiter, who probably got smacked upside the head for not knowing enough to use tongs.

We ordered the four-course "seasonal menu," so we ate all the same things. The first course was cold velvety pea soup, caviar, perlines de lulo, and citronella panna cotta (garnished with Oxalis,, chickweed, and lemon verbena. It came topped with this lacy cookie, but at the right you can see it with the partially eaten cookie pushed aside to reveal the soup.

It took some invesigation to figure out what "perlines de lulo" are, and I'm still not sure I got it right. Googling the phrase turns up no hits except references to the menu at Laurent, and "perlines" are just tiny beads, but a "lulo" turns out to be Solanum quitoense, the naranjilla, a South American tomato relative, so maybe there were bits of naranjilla in the soup. I didn't see them. You can see a little of the panna cotta, which was a layer inthe bottom of the bowl, poking up near the middle where I dug it up with my spoon.

Second course: Lobster cooked in a bouillon of kombu (a marine alga), Szechuan pepper, and juniper berries, with ravioles of peas and white asparagus. That was the menu description, but I don't recall any ravioles or see any in the photo—I think we got artichoke bottoms instead, as well as a few peas, bits of orange and lemon flesh, and slices of a strange little berry that looked just like a tiny watermelon on the outside but more like a green cherry tomato on the inside. Mayby they were green cherry tomatoes.

Second course: Lobster cooked in a bouillon of kombu (a marine alga), Szechuan pepper, and juniper berries, with ravioles of peas and white asparagus. That was the menu description, but I don't recall any ravioles or see any in the photo—I think we got artichoke bottoms instead, as well as a few peas, bits of orange and lemon flesh, and slices of a strange little berry that looked just like a tiny watermelon on the outside but more like a green cherry tomato on the inside. Mayby they were green cherry tomatoes.

Third course: Roasted lamb filet with tortellini of fava beans and ricotta, vegetable chips, and Parmesan. Yummy. A couple of the vegetable chips were slices of truffle.

We interrupted the four-course dinner to have cheese from the trolley. (Because getting from the building to the garden entailed a step down, two waiters had to lift the cheese trolley down and then back up every time somebody dining outside (and that was almost everybody when we were there) ordered cheese. David had Roquefort, Brillat-Savarin, and Comté, three of his favorites. I had Brillat-Savarin, a brillianly red-rinded thing called Murol that I'd never seen before, and a Corsican Brin d'Amour, which I found too heavily herbed and not to my taste. The Murol was great, though. You can see the brilliantly colored rind on my plate, after I'd already dug out and eaten the middle.

We interrupted the four-course dinner to have cheese from the trolley. (Because getting from the building to the garden entailed a step down, two waiters had to lift the cheese trolley down and then back up every time somebody dining outside (and that was almost everybody when we were there) ordered cheese. David had Roquefort, Brillat-Savarin, and Comté, three of his favorites. I had Brillat-Savarin, a brillianly red-rinded thing called Murol that I'd never seen before, and a Corsican Brin d'Amour, which I found too heavily herbed and not to my taste. The Murol was great, though. You can see the brilliantly colored rind on my plate, after I'd already dug out and eaten the middle.

While we waited for our dessert—hot strawberry-ginger soufflé—we were served a predessert of palmiers, a sort of pastry or cookie made of buttery puff pastry and sugar; they're sometimes called "elephant ears" or "palm leaves" in English. They're usually pretty good, but these were beyond outstanding. It was all I could do not to eat all of them! I'd go back to that restaurant just to have those again!

The soufflé was great but was almost anticlimactic after the palmiers.

The soufflé was great but was almost anticlimactic after the palmiers.

The mignardises were an assortment of little tartlets: cherry pistachio, fruit cake, and chocolate, but they got short shrift, I'm afraid.

The meal included two other highlights: First, every few minutes we got to watch the waiters prepare the lobster salad, which was apparently quite popular. They would appear with a trolley bearing salad fixings and a cutting board bearing a whole cooked lobster. The waiters would then dismember the lobster, extract the claw and tail meat, slice it, and, after dressing and tossing the salad, arrange the slices neatly over it, and serve it to the customer. The lobster body went back to the kitchen (with me gazing wistfully after it; I could have had that or dessert). I hope they at least used them to make lobster rolls for the next day or boiled them down crushed them for a sauce . . . David, on the other hand, was gazing wistfully at the claw and tail meat, presented to diners already shucked. He remarked that that was how he like to have his lobster, so from now on, I'll to have serve him more "boneless" lobster dishes (for me, half the fun of a lobster dinner is shucking the lobster).

The other highlight was a bird, a coal tit, that was foraging among the tables for dropped crumbs. I laid out a few of appropriate size to see if he would come to the table for them. (The waiters were fanatical about crumbs and kept sweeping our table between courses, so I had to ask them to stop, pointing out that I was trying to feed the birds. They were fine with that.) And, yes, the coal tit did come down to take advantage of my array of treats, carrying each one off to the branches of the large horse chestnut tree by our table.

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

After splitting the giant sugared brioche for breakfast, we set off once again for La Villette, and this time had no trouble getting in. I had even bought tickets on line and managed to get them onto my cell phone so they could be scanned at the door. Lesson for next time, though:L Some, but not all, on-line ticket sellers offer the option to send the tickets to your smart phone. For those that don't, because they assume you have a printer, it is a real pain to get those tickets onto your phone and then to find them again when you need them. For our next trip, I'm doing more advance research on prepurchased tickets and printing them out before I leave home. Those work like a charm. The ones bought at the last minute might have worked better if we'd been in a hotel, where I could have asked the office to print them for me or used the "business center" in the lobby.

After splitting the giant sugared brioche for breakfast, we set off once again for La Villette, and this time had no trouble getting in. I had even bought tickets on line and managed to get them onto my cell phone so they could be scanned at the door. Lesson for next time, though:L Some, but not all, on-line ticket sellers offer the option to send the tickets to your smart phone. For those that don't, because they assume you have a printer, it is a real pain to get those tickets onto your phone and then to find them again when you need them. For our next trip, I'm doing more advance research on prepurchased tickets and printing them out before I leave home. Those work like a charm. The ones bought at the last minute might have worked better if we'd been in a hotel, where I could have asked the office to print them for me or used the "business center" in the lobby.

Here, at the left, is another planning model (for Roman Polanski's Le Locataire, called The Tenant in English). It rests on a floor plan of the entire castle of which it represents only a part.

Here, at the left, is another planning model (for Roman Polanski's Le Locataire, called The Tenant in English). It rests on a floor plan of the entire castle of which it represents only a part.

Here are a couple of animatronic gremlins from the movies of that name. The exhibition also went into great detail about make-up and prosthetics, using as one example the costuming from the Planet of the Apes movies, which also included motion capture—we saw films of Andy Serkis doing the motion-capture scenes as well as the movies scenes that resulted.

Here are a couple of animatronic gremlins from the movies of that name. The exhibition also went into great detail about make-up and prosthetics, using as one example the costuming from the Planet of the Apes movies, which also included motion capture—we saw films of Andy Serkis doing the motion-capture scenes as well as the movies scenes that resulted.

We found lunch at "Le Rest'" on the lower level. David had beef tartare with fries, which was quite good. I had an only-okay salad nicoise, once again with olives of no particular character.

We found lunch at "Le Rest'" on the lower level. David had beef tartare with fries, which was quite good. I had an only-okay salad nicoise, once again with olives of no particular character.

For dessert, we split a panna cotta with mango coulis.

For dessert, we split a panna cotta with mango coulis.

We also passed through the building's large central atrium, where I got shots from slightly above and slightly below a solar-powered airplane. "Solvay" is a Belgian company that presumably helped build it; along the tail it says "SolarImpulse across the U.S.A."

We also passed through the building's large central atrium, where I got shots from slightly above and slightly below a solar-powered airplane. "Solvay" is a Belgian company that presumably helped build it; along the tail it says "SolarImpulse across the U.S.A."

The entrance to the cold exhibit was through a winding path along a figurative gradient from 0°C to absolute zero. Every few steps, graphics and text would signal some some particularly significant temperature—lowest temperature in a home freezer, temperature of frozen carbon dioxide, temperature of frozen oxygen, etc. The last temperature at which anything was indicated was this one (left), 0.05°K, at which a small sign and photo indicated that tardigrades (commonly called water bears, at least among those who've ever heard of them) could survive for several hours. Tardigrades! Who knew?! Let's hear it for the meiofauna!

The entrance to the cold exhibit was through a winding path along a figurative gradient from 0°C to absolute zero. Every few steps, graphics and text would signal some some particularly significant temperature—lowest temperature in a home freezer, temperature of frozen carbon dioxide, temperature of frozen oxygen, etc. The last temperature at which anything was indicated was this one (left), 0.05°K, at which a small sign and photo indicated that tardigrades (commonly called water bears, at least among those who've ever heard of them) could survive for several hours. Tardigrades! Who knew?! Let's hear it for the meiofauna!

For dinner, we went to Le Laurent, which is located in the Jardin des Champs l'Elysées (a park one block by two long blocks that parallels the Champs Elysées from the Place de la Concorde to the Rond Point. There we were, in a lovely walled, tree-shaded garden, just a block off the Champs Élysées and about a block and a half from the French presidential palace.

For dinner, we went to Le Laurent, which is located in the Jardin des Champs l'Elysées (a park one block by two long blocks that parallels the Champs Elysées from the Place de la Concorde to the Rond Point. There we were, in a lovely walled, tree-shaded garden, just a block off the Champs Élysées and about a block and a half from the French presidential palace.

Strangely, we were then served warm slices of toast. The waiter extended the basket and lifted the napkin, inviting us to take them with our fingers, which struck me as odd for a restaurant of this calibre, where even when they bring you a fresh napkin (should you, for example, drop yours on the floor), they hand it to you with tongs. A few minutes later, I saw toast being served to another table, this time with tongs, and a few minutes after that, regular small breads appeared and were served (with tongs) to everyone for the rest of the evening. My theory is that the baker ran late, and the small breads weren't ready by the time the waiters thought we should have bread, so they improvised and toasted slices of bread left from the lunch service. We probably got the junior-most waiter, who probably got smacked upside the head for not knowing enough to use tongs.

Strangely, we were then served warm slices of toast. The waiter extended the basket and lifted the napkin, inviting us to take them with our fingers, which struck me as odd for a restaurant of this calibre, where even when they bring you a fresh napkin (should you, for example, drop yours on the floor), they hand it to you with tongs. A few minutes later, I saw toast being served to another table, this time with tongs, and a few minutes after that, regular small breads appeared and were served (with tongs) to everyone for the rest of the evening. My theory is that the baker ran late, and the small breads weren't ready by the time the waiters thought we should have bread, so they improvised and toasted slices of bread left from the lunch service. We probably got the junior-most waiter, who probably got smacked upside the head for not knowing enough to use tongs.

Second course: Lobster cooked in a bouillon of kombu (a marine alga), Szechuan pepper, and juniper berries, with ravioles of peas and white asparagus. That was the menu description, but I don't recall any ravioles or see any in the photo—I think we got artichoke bottoms instead, as well as a few peas, bits of orange and lemon flesh, and slices of a strange little berry that looked just like a tiny watermelon on the outside but more like a green cherry tomato on the inside. Mayby they were green cherry tomatoes.

Second course: Lobster cooked in a bouillon of kombu (a marine alga), Szechuan pepper, and juniper berries, with ravioles of peas and white asparagus. That was the menu description, but I don't recall any ravioles or see any in the photo—I think we got artichoke bottoms instead, as well as a few peas, bits of orange and lemon flesh, and slices of a strange little berry that looked just like a tiny watermelon on the outside but more like a green cherry tomato on the inside. Mayby they were green cherry tomatoes.

We interrupted the four-course dinner to have cheese from the trolley. (Because getting from the building to the garden entailed a step down, two waiters had to lift the cheese trolley down and then back up every time somebody dining outside (and that was almost everybody when we were there) ordered cheese. David had Roquefort, Brillat-Savarin, and Comté, three of his favorites. I had Brillat-Savarin, a brillianly red-rinded thing called Murol that I'd never seen before, and a Corsican Brin d'Amour, which I found too heavily herbed and not to my taste. The Murol was great, though. You can see the brilliantly colored rind on my plate, after I'd already dug out and eaten the middle.

We interrupted the four-course dinner to have cheese from the trolley. (Because getting from the building to the garden entailed a step down, two waiters had to lift the cheese trolley down and then back up every time somebody dining outside (and that was almost everybody when we were there) ordered cheese. David had Roquefort, Brillat-Savarin, and Comté, three of his favorites. I had Brillat-Savarin, a brillianly red-rinded thing called Murol that I'd never seen before, and a Corsican Brin d'Amour, which I found too heavily herbed and not to my taste. The Murol was great, though. You can see the brilliantly colored rind on my plate, after I'd already dug out and eaten the middle.

The soufflé was great but was almost anticlimactic after the palmiers.

The soufflé was great but was almost anticlimactic after the palmiers.