Friday, 14 June, Science with 500,000 five-year-olds and Frédéric Simonin

Written 16 June 2019

Last year's special exhibitions at the Cité de la Science et de l'Industrie—"Special Effects" and "Cold"—were so good that we decided to head out there again to see a couple that were on the docket for this year—"Gut Microbiota" and "High-Speed Rail." I chose a Friday on the theory that fewer families with children would be there than on weekends. Unfortunately, it turned out to be kindergarten day at the Cité. Every class of five-year-olds in Paris was there, each accompanied by a teacher and several aides/auxiliaries to try to keep them in line, but that was an uphill battle. Some classes wore miniature versions of those mesh vests in dayglo colors that road workers wear to make themselves visible. Those classes therefore formed color blocks that helped keep them together. Others just wore their ordinary clothes, so their teachers had to keep track of the members of their groups by line-of-sight and shouting. And speaking of shouting . . . in the tiny throats of the kids, it was more like shrieking, and it was loud and continuous—they were all so excited to be there!

We started with the gut microbiota, which turned out to be aimed at the younger set. Not that there wasn't a lot of real, valid information in there, much of which I didn't know, but not one microbe was portrayed as anything but a cartoon character. It was apparently based on a book, presumably for children, called Le Charme Discret de l'Intestin, whose point is to recommend 10 steps for a healthy intestine and therefore a healthy life.

We started with the gut microbiota, which turned out to be aimed at the younger set. Not that there wasn't a lot of real, valid information in there, much of which I didn't know, but not one microbe was portrayed as anything but a cartoon character. It was apparently based on a book, presumably for children, called Le Charme Discret de l'Intestin, whose point is to recommend 10 steps for a healthy intestine and therefore a healthy life.

At the right here, David stands by the entrance to the exhibition, an open mouth through which one walks, and, yes, the exit is just what you'd expect. In between you pass through all areas of the alimentary tract, learning what each does and how, sometimes quite graphically. The array of models demonstrating the proper form and consistency of stool (and, at each extreme of the spectrum, the improper form and consistency) was so mobbed with little boys that it was hard to get close enough to see. The kids also delighted in a hole in the wall out of which you could pull cords—first a thin one and then a much thicker, padded one—to get an idea just how long the human small and large intestines are. In front of a mirror, you could stand behind frames supporting drawings of the stomach and intestinal tract to see just where they are situated inside you—the stomach is much higher up than most people think. A model stomach filled with liquid and an air bubble could be rotated from side to side and emitted a realistic belching sound when you lined the bubble up with the esophagus (which actually enters from the side, allowing gas to accumulate above it, under the stomach "dome" as it were).

A stop-motion animated movie presented many activities that take place in the intestine. The background and all the characters were made of wool. Some of the interactions are friendly, and some of the characters (e.g. pathogens) are creepy.

A stop-motion animated movie presented many activities that take place in the intestine. The background and all the characters were made of wool. Some of the interactions are friendly, and some of the characters (e.g. pathogens) are creepy.

On the floor below the screen, you can just make out the loops of the large intestine, and even some of the small one, which kids pulled out and then didn't push back in.

<

<

At the left here, a line of good guys sit around looking like doofuses, until confronted with the small orange pathogen, whom they deal with summarily.

At the left here, a line of good guys sit around looking like doofuses, until confronted with the small orange pathogen, whom they deal with summarily.

Farther along in the exhibition was a video demonstration of what kind of enzyme attacks glucose, what kind galactose, etc. (both enzymes and sugars presented as cartoons), then, on the same screen you got to play a video game (left). The relevant enzymes, antibodies, etc., lie on the floor of the intestine while a stream of sugars, pathogens, etc. float by above. The player must drag the correct element from the floor up to each passing globule so as to deal with them all correctly. The adults were actually having a good time with that one.

Another point the exhibition made—through elaborate diagrams and explanation—is that the "squatty potty" people are right. Who knew?

Once we had exhausted the funds of information provided by the exhibition, we waded hip deep through the children and out through the exit (much to the delight of little boys already on the other side) and went in search of lunch.

Once we had exhausted the funds of information provided by the exhibition, we waded hip deep through the children and out through the exit (much to the delight of little boys already on the other side) and went in search of lunch.

"Microbiota" was on level +1, whereas our target restaurant (the same one we ate at last year) was on level -2, but apparently no escalator or elevator connects the two directly. No matter where you're going, you have to go to level 0, then look for the way up or down to where you want to go. On level 0, we tried to visit the restrooms, but the queue for the ladies, not just of five-year-olds but of classes of five-year-olds was prohibitive. David gave up, too, saying that the men's room had been commandeered for five-year-girls, and that teachers stood guard at the door.

Level -2, though, proved to be an oasis of calm and had its own (empty) toilets. We presented ourselves at Rest'O, our eatery of choice and were seated at a table right by the aquarium. The museum's aquarium is relatively small, comprising a 10,000-liter, a 40,000-liter, and an 80,000-liter tank. The walk through it is just one short loop, around the two larger tanks and past the third, which is to one side. The restaurant's indoor seating is wrapped around part of the loop (last year we sat on the terrace and missed it). So while we ate our "moules à la crème" (mussels in a sauce of cream and onions) and fries, we watched sea bass, sea bream, and eels swim around.

About half-way through the meal, the first five-year-olds showed up, shrieking with delight at seeing the fish. (Teachers shouted continuously, "Thierry, you're too far ahead; come back. Marie, don't bang on the glass. Etiènne, don't straggle; keep up. Max, put your vest back on.") Our table was slightly elevated with respect to the walk through the aquarium, and we were protected by a low wall from the mayhem.

After luch, we decided to take a quick turn through the aquarium, despite the continued waves of arriving munchkins. The labels for the various fish species were on tall, lighted blue cylinders beside the tanks—each cylinder could be turned to display four columns of fish. I had considerable trouble getting this shot of one, as the kids were much more interested in spinning them continuously than in reading what they said. You can see all the little hands, ready to set it in motion again.

I got this shot of a cute little flatfish (I think it's a "rombou podas" (Bothas podas, wide-eyed flounder), but I'm not sure, as all the labels were spinning. He was maybe the size of my hand.

I got this shot of a cute little flatfish (I think it's a "rombou podas" (Bothas podas, wide-eyed flounder), but I'm not sure, as all the labels were spinning. He was maybe the size of my hand.

In the larger tank, I caught a few of the larger fishes. I can see a couple of bar in there (Dicentrarchus labrax, sea bass) and at least two of they six or sevel species of seabream—all yummy Mediterranean speciesj. Around the curve, lurking in a hole in rocks, was a solitary grouper of some kind, and the tank had both moray and conger eels.

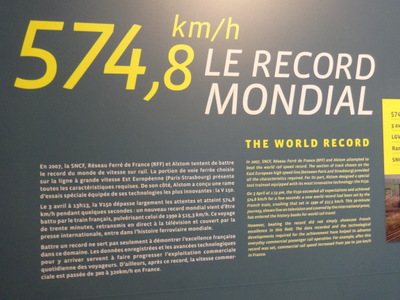

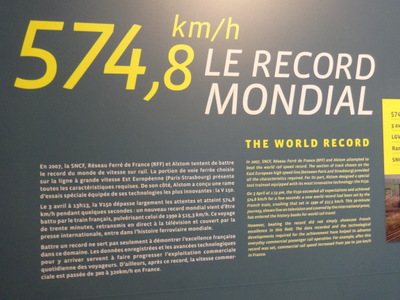

Then it was off to high-speed rail, on level +2. David expected it to talk about the mag-lev trains of the future, but in fact is was all about rail, and more specifically centered on the elaborate preparations that went into the setting, in 2007, of a new world rail speed record by a team from the French railway system: 574.8 km/hour.

Then it was off to high-speed rail, on level +2. David expected it to talk about the mag-lev trains of the future, but in fact is was all about rail, and more specifically centered on the elaborate preparations that went into the setting, in 2007, of a new world rail speed record by a team from the French railway system: 574.8 km/hour.

The exhibition also featured a few works of art relevant to rail travel, the first of which is shown here. It's a life-size model of a train bursting through a billboard that purports to advertise a (fictional) movie called La Motrice (The Locomotive), and it is wonderful! The photo at the right is a closer shot of the near side of the cab—the train's "copilot" stares in wide-eyed shock, the ketchup and mustard are squirting out of his hotdog, which was on its way to his mouth. His box of fries is in mid-air, as is his beer bottle, which is flipping over and spilling its contents, also suspended in mid-air. The main engineer, on the other side, looks just as shocked but is actually trying to stop the train.

At the wheels (just below the boundary between the painted portion of the engine and the bare metal behind it, sparks shooting from the brakes are suspended in time, and on a strut next to them, an equally shocked-looking rat is clinging for dear life.

The artist, Jean-Michel Caillebotte, says (in my translation) of this 2017 work: "I wanted to play with the paradox of speed and time, to work with that sensation one has in a moving train. One is immobile and in motion. Outside, the landscape goes by at great speed, while the traveler waits in a slowed time, far from the unbraked rhythm of daily life. This reflection led me to think of this installation in suspended time, a form of freeze-frame as in a movie, which would give me the possibility of showing with humor a dynamic of the instant and to restore faithfully the speed of the action in passing from the second to the third dimension." Cool.

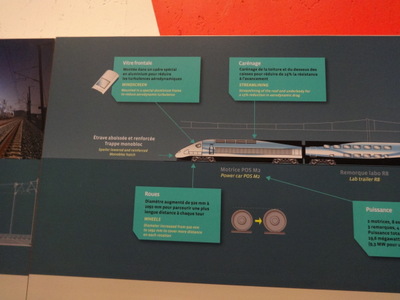

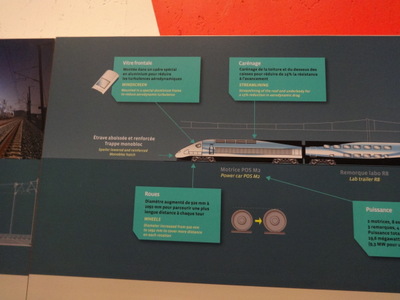

I have to say I was impressed with the number of factors that went into setting up the record run. The "trame" (translated "train set") used consisted of two engines (one in front and the other at the end) and three carriages in between. First they chose the best stretch of track (a nice straight one between Paris and Belgium), then they increased the streamlining (smoothing the windshield mounting and the roof and undercarriage, lowering and modifying the "spoiler" under the locomotive's nose), increased the diameter of the wheels slightly to get more distance on each turn, adjusted the tension on the overhead cables delivering power and raised the power from the usual 9.3 megawatts to 19.6, used just one pantograph (the jointed pole on top of the train that maintains contact with the power cable and delivers the power to the engine) rather than the usual two to lower wind resistance, shifted the positions of what they translated "bogies" but I would have called "wheel trucks" so that they spanned the joints between cars rather than each being under one end of its own car, and then relentlessly optimized everything. For example, they carried out many trials to arrive at just the right amount of friction between the wheels and the rails—enough to provide traction but not enough to pose resistance. The displays emphasized that the contact between the train and the tracks is limited to little patches about the size of a post-it note, one for each wheel, so getting that contact just right was really important. They even optimized the ballast—the rocks piled around and between the sleepers and the rails—it had to resist being vibrated or blown out of place.

I have to say I was impressed with the number of factors that went into setting up the record run. The "trame" (translated "train set") used consisted of two engines (one in front and the other at the end) and three carriages in between. First they chose the best stretch of track (a nice straight one between Paris and Belgium), then they increased the streamlining (smoothing the windshield mounting and the roof and undercarriage, lowering and modifying the "spoiler" under the locomotive's nose), increased the diameter of the wheels slightly to get more distance on each turn, adjusted the tension on the overhead cables delivering power and raised the power from the usual 9.3 megawatts to 19.6, used just one pantograph (the jointed pole on top of the train that maintains contact with the power cable and delivers the power to the engine) rather than the usual two to lower wind resistance, shifted the positions of what they translated "bogies" but I would have called "wheel trucks" so that they spanned the joints between cars rather than each being under one end of its own car, and then relentlessly optimized everything. For example, they carried out many trials to arrive at just the right amount of friction between the wheels and the rails—enough to provide traction but not enough to pose resistance. The displays emphasized that the contact between the train and the tracks is limited to little patches about the size of a post-it note, one for each wheel, so getting that contact just right was really important. They even optimized the ballast—the rocks piled around and between the sleepers and the rails—it had to resist being vibrated or blown out of place.

Near the end, they presented a chart of various careers to be had in rail transport, about 20 of them, from bulldozer operator to electrician to designer to surveyor to engine mechanic.

Finally we visited another of the works of art. We had been hearing gales of laughter and shrieking from the kids, as they cycled through. It was a 3D movie (glasses provided) involving two human characters and a cartoon TGV train that, on several occasions zoomed out of the screen to stop (apparently) about two feet from the viewer. The first time, you could see a couple of engineers sitting behind the windshield, but on successive lunges, it had glowing eyes like a snake or dragon, and in all cases, it opened its snakelike mouth and roared—concealed nozzels blew air in the viewer's face in perfect synchrony. A very effective illusion!

Once again, our feet gave out before we covered much else beyond those two exhibitions. Fortunately, the new one on robots is going to be permanent, so we'll probably get another chance. Finally, we trekked back across the parvis to the Metro and trundled home to rest up.

Dinner was only a short walk away, and our reservation, at Restaurant Freédéric Simonin, was uncharacteristically early—7:30 p.m. We set off in plenty of time, passing this appetizing assortment of pastries on the way, and got there about 15 min early.

Dinner was only a short walk away, and our reservation, at Restaurant Freédéric Simonin, was uncharacteristically early—7:30 p.m. We set off in plenty of time, passing this appetizing assortment of pastries on the way, and got there about 15 min early.

Now I never make reservations at 7:30 p.m. by choice. I always go for 8:00 p.m. unless prevented—we were prevented three times this year, so we have one at 7:30, one at 7:00(!), and one at 8:30 p.m. Usually, the reason is that the restaurant doesn't have any availability at 8:00 p.m. or organizes two seatings, at set times. This year, one restaurant e-mailed apologetically to ask whether our time could be moved to an earlier one, but I don't remember which one that was. Anyway, we window-shopped nearby to kill a little time, then presented ourselves at the door, only to find it locked! But the lights were on and the tables were set, so we did not dispair. Back to window shopping. Tried the door again at 7:35 p.m., and it was still locked! So we stood around on the sidewalk, took a photo of the entrance, etc., until finally, at about 7:40 p.m., they let us in, looked at us as if we were nuts, and seated us in the deserted dining room. I ground my teeth and refrained from pointing out that a 7:30 reservation was their idea, not mine!

Other diners eventually arrived, although the room never filled up. I have no idea why they wouldn't give us an 8:00 reservation.

Anyway, the food was very good, though the recent trend of asking you after every course whether you liked it, whether everything is going well, etc. was carried to extremes here—those waiters were a really needy bunch, begging constantly for reassurance.

With David's glass of champagne, we got a warm, bacon-flecked madeleine and a small glass filled with, from the bottom, a foie gras custard, a layer of port-wine reduction, and a Parmesan-flavored foam. We were instructed to dip all the way to the bottom, so as to get all the flavors together. Some critics get annoyed at waiters who tell them how to eat their food, but I mostly just ignore them (especially when they tell me what order to each my cheese in, from mildest to strongest; I like to skip around). I am usually willing to do the dip-all-the-way-down thing, though, at least on the first bite.

With David's glass of champagne, we got a warm, bacon-flecked madeleine and a small glass filled with, from the bottom, a foie gras custard, a layer of port-wine reduction, and a Parmesan-flavored foam. We were instructed to dip all the way to the bottom, so as to get all the flavors together. Some critics get annoyed at waiters who tell them how to eat their food, but I mostly just ignore them (especially when they tell me what order to each my cheese in, from mildest to strongest; I like to skip around). I am usually willing to do the dip-all-the-way-down thing, though, at least on the first bite.

This was another multicourse surprise tasting menu, so we ate all the same things. The official amuse-bouche was diced raw Scottish salmon and tiny spheres of cooked potato topped with a green Vichyssoise-flavored purée of parsley, potato, and leek. Tiny black croutons sprinkled over all. The especially pointed out the aromatic sprig of "tagète" in the middle. It was clearly a sprig of marigold (genus Tagetes), but I don't know whether it was a variety different from the common garden flower, which the French call a "souci."

The first course was a cold white asparagus soup with a veritable flower garden sprinkled on top: slices of cooked white asparagus, slices of crispy raw daikon, wild asparagus tips, chive flowers, pansy petals, some other little white weed flower, dabs of caviar, cubes of orange-grapefruit jelly, and finally eensy little four-petaled purple flowers I couldn't identify. Yummy.

The first course was a cold white asparagus soup with a veritable flower garden sprinkled on top: slices of cooked white asparagus, slices of crispy raw daikon, wild asparagus tips, chive flowers, pansy petals, some other little white weed flower, dabs of caviar, cubes of orange-grapefruit jelly, and finally eensy little four-petaled purple flowers I couldn't identify. Yummy.

I don't include a photo here, but they baked special bread for David. He can't eat buckwheat, and their regular bread, which they served to me throughout the meal, has buckwheat in it, so for him they baked up four miniature loaves of their gluten-free bread, the only one they had without buckwheat—it was pretty good bread, too!

Second course: A gigantic razor clam, marinated and diced for ease of eating, set in the shell in a yuzu jelly and decorated with tiny spheres of raw apple and again with all manner of tiny flowers and etiolated clover leaves. The red things were also apparently marinated shellfish of some sort, but I'm not sure whether they were part of the clams or some other species We were warned that the round white pedestal was rock salt and not intended for consumption.

Third course, rouget (red mullet) filet topped with piquillo-pepper tuiles, and served with lemon gnocchi (topped with more of those tiny white weed flowers, very flavorful), a bright red reduction sauce, a saffron sauce, and an agar ball filled with what might just have been more of the reduction sauce.

Third course, rouget (red mullet) filet topped with piquillo-pepper tuiles, and served with lemon gnocchi (topped with more of those tiny white weed flowers, very flavorful), a bright red reduction sauce, a saffron sauce, and an agar ball filled with what might just have been more of the reduction sauce.

Fourth course: quail, leg and boneless breast (the latter stuffed with foie gras) topped with shaved black truffles. On the side, a cube-shaped leaf of swiss chard stuffed with (we think) veal and topped with a section of chard stem and then by a spherical soufléed potato chip.

The fifth course was a ball of extremely intense raspberry sorbet enclosing a smaller ball of basil sorbet, decorated with red and white shards. The red shards were chocolate and the white one were crisp meringue, the element justifying their calling it a "vacherin" rather than just a ball of sorbet.

The fifth course was a ball of extremely intense raspberry sorbet enclosing a smaller ball of basil sorbet, decorated with red and white shards. The red shards were chocolate and the white one were crisp meringue, the element justifying their calling it a "vacherin" rather than just a ball of sorbet.

I would have preferred the raspberry sorbet without the seeds, and it seemed to be that the basil was entirely overwhelmed by the raspberry—you couldn't taste it at all.

The sixth and last course was the inevitable chocolate dessert: A quenelle of chocolate sorbet resting on a thin, round chocolate cookie, in turn resting on a disk of rich chocolate ganache. Skinny decorative chocolate rods. Dratted gold foil on top.

The sixth and last course was the inevitable chocolate dessert: A quenelle of chocolate sorbet resting on a thin, round chocolate cookie, in turn resting on a disk of rich chocolate ganache. Skinny decorative chocolate rods. Dratted gold foil on top.

The mignardises were dark chocolate filled with liquid salted caramel, hemispheres of black-currant fruit paste, and very flavorful passion-fruit marshmallows. I actually ate one of each!

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

We started with the gut microbiota, which turned out to be aimed at the younger set. Not that there wasn't a lot of real, valid information in there, much of which I didn't know, but not one microbe was portrayed as anything but a cartoon character. It was apparently based on a book, presumably for children, called Le Charme Discret de l'Intestin, whose point is to recommend 10 steps for a healthy intestine and therefore a healthy life.

We started with the gut microbiota, which turned out to be aimed at the younger set. Not that there wasn't a lot of real, valid information in there, much of which I didn't know, but not one microbe was portrayed as anything but a cartoon character. It was apparently based on a book, presumably for children, called Le Charme Discret de l'Intestin, whose point is to recommend 10 steps for a healthy intestine and therefore a healthy life.

A stop-motion animated movie presented many activities that take place in the intestine. The background and all the characters were made of wool. Some of the interactions are friendly, and some of the characters (e.g. pathogens) are creepy.

A stop-motion animated movie presented many activities that take place in the intestine. The background and all the characters were made of wool. Some of the interactions are friendly, and some of the characters (e.g. pathogens) are creepy.

At the left here, a line of good guys sit around looking like doofuses, until confronted with the small orange pathogen, whom they deal with summarily.

At the left here, a line of good guys sit around looking like doofuses, until confronted with the small orange pathogen, whom they deal with summarily.

Once we had exhausted the funds of information provided by the exhibition, we waded hip deep through the children and out through the exit (much to the delight of little boys already on the other side) and went in search of lunch.

Once we had exhausted the funds of information provided by the exhibition, we waded hip deep through the children and out through the exit (much to the delight of little boys already on the other side) and went in search of lunch.

I got this shot of a cute little flatfish (I think it's a "rombou podas" (Bothas podas, wide-eyed flounder), but I'm not sure, as all the labels were spinning. He was maybe the size of my hand.

I got this shot of a cute little flatfish (I think it's a "rombou podas" (Bothas podas, wide-eyed flounder), but I'm not sure, as all the labels were spinning. He was maybe the size of my hand.

Then it was off to high-speed rail, on level +2. David expected it to talk about the mag-lev trains of the future, but in fact is was all about rail, and more specifically centered on the elaborate preparations that went into the setting, in 2007, of a new world rail speed record by a team from the French railway system: 574.8 km/hour.

Then it was off to high-speed rail, on level +2. David expected it to talk about the mag-lev trains of the future, but in fact is was all about rail, and more specifically centered on the elaborate preparations that went into the setting, in 2007, of a new world rail speed record by a team from the French railway system: 574.8 km/hour.

I have to say I was impressed with the number of factors that went into setting up the record run. The "trame" (translated "train set") used consisted of two engines (one in front and the other at the end) and three carriages in between. First they chose the best stretch of track (a nice straight one between Paris and Belgium), then they increased the streamlining (smoothing the windshield mounting and the roof and undercarriage, lowering and modifying the "spoiler" under the locomotive's nose), increased the diameter of the wheels slightly to get more distance on each turn, adjusted the tension on the overhead cables delivering power and raised the power from the usual 9.3 megawatts to 19.6, used just one pantograph (the jointed pole on top of the train that maintains contact with the power cable and delivers the power to the engine) rather than the usual two to lower wind resistance, shifted the positions of what they translated "bogies" but I would have called "wheel trucks" so that they spanned the joints between cars rather than each being under one end of its own car, and then relentlessly optimized everything. For example, they carried out many trials to arrive at just the right amount of friction between the wheels and the rails—enough to provide traction but not enough to pose resistance. The displays emphasized that the contact between the train and the tracks is limited to little patches about the size of a post-it note, one for each wheel, so getting that contact just right was really important. They even optimized the ballast—the rocks piled around and between the sleepers and the rails—it had to resist being vibrated or blown out of place.

I have to say I was impressed with the number of factors that went into setting up the record run. The "trame" (translated "train set") used consisted of two engines (one in front and the other at the end) and three carriages in between. First they chose the best stretch of track (a nice straight one between Paris and Belgium), then they increased the streamlining (smoothing the windshield mounting and the roof and undercarriage, lowering and modifying the "spoiler" under the locomotive's nose), increased the diameter of the wheels slightly to get more distance on each turn, adjusted the tension on the overhead cables delivering power and raised the power from the usual 9.3 megawatts to 19.6, used just one pantograph (the jointed pole on top of the train that maintains contact with the power cable and delivers the power to the engine) rather than the usual two to lower wind resistance, shifted the positions of what they translated "bogies" but I would have called "wheel trucks" so that they spanned the joints between cars rather than each being under one end of its own car, and then relentlessly optimized everything. For example, they carried out many trials to arrive at just the right amount of friction between the wheels and the rails—enough to provide traction but not enough to pose resistance. The displays emphasized that the contact between the train and the tracks is limited to little patches about the size of a post-it note, one for each wheel, so getting that contact just right was really important. They even optimized the ballast—the rocks piled around and between the sleepers and the rails—it had to resist being vibrated or blown out of place.

Dinner was only a short walk away, and our reservation, at Restaurant Freédéric Simonin, was uncharacteristically early—7:30 p.m. We set off in plenty of time, passing this appetizing assortment of pastries on the way, and got there about 15 min early.

Dinner was only a short walk away, and our reservation, at Restaurant Freédéric Simonin, was uncharacteristically early—7:30 p.m. We set off in plenty of time, passing this appetizing assortment of pastries on the way, and got there about 15 min early.

With David's glass of champagne, we got a warm, bacon-flecked madeleine and a small glass filled with, from the bottom, a foie gras custard, a layer of port-wine reduction, and a Parmesan-flavored foam. We were instructed to dip all the way to the bottom, so as to get all the flavors together. Some critics get annoyed at waiters who tell them how to eat their food, but I mostly just ignore them (especially when they tell me what order to each my cheese in, from mildest to strongest; I like to skip around). I am usually willing to do the dip-all-the-way-down thing, though, at least on the first bite.

With David's glass of champagne, we got a warm, bacon-flecked madeleine and a small glass filled with, from the bottom, a foie gras custard, a layer of port-wine reduction, and a Parmesan-flavored foam. We were instructed to dip all the way to the bottom, so as to get all the flavors together. Some critics get annoyed at waiters who tell them how to eat their food, but I mostly just ignore them (especially when they tell me what order to each my cheese in, from mildest to strongest; I like to skip around). I am usually willing to do the dip-all-the-way-down thing, though, at least on the first bite.

The first course was a cold white asparagus soup with a veritable flower garden sprinkled on top: slices of cooked white asparagus, slices of crispy raw daikon, wild asparagus tips, chive flowers, pansy petals, some other little white weed flower, dabs of caviar, cubes of orange-grapefruit jelly, and finally eensy little four-petaled purple flowers I couldn't identify. Yummy.

The first course was a cold white asparagus soup with a veritable flower garden sprinkled on top: slices of cooked white asparagus, slices of crispy raw daikon, wild asparagus tips, chive flowers, pansy petals, some other little white weed flower, dabs of caviar, cubes of orange-grapefruit jelly, and finally eensy little four-petaled purple flowers I couldn't identify. Yummy.

Third course, rouget (red mullet) filet topped with piquillo-pepper tuiles, and served with lemon gnocchi (topped with more of those tiny white weed flowers, very flavorful), a bright red reduction sauce, a saffron sauce, and an agar ball filled with what might just have been more of the reduction sauce.

Third course, rouget (red mullet) filet topped with piquillo-pepper tuiles, and served with lemon gnocchi (topped with more of those tiny white weed flowers, very flavorful), a bright red reduction sauce, a saffron sauce, and an agar ball filled with what might just have been more of the reduction sauce.

The fifth course was a ball of extremely intense raspberry sorbet enclosing a smaller ball of basil sorbet, decorated with red and white shards. The red shards were chocolate and the white one were crisp meringue, the element justifying their calling it a "vacherin" rather than just a ball of sorbet.

The fifth course was a ball of extremely intense raspberry sorbet enclosing a smaller ball of basil sorbet, decorated with red and white shards. The red shards were chocolate and the white one were crisp meringue, the element justifying their calling it a "vacherin" rather than just a ball of sorbet.

The sixth and last course was the inevitable chocolate dessert: A quenelle of chocolate sorbet resting on a thin, round chocolate cookie, in turn resting on a disk of rich chocolate ganache. Skinny decorative chocolate rods. Dratted gold foil on top.

The sixth and last course was the inevitable chocolate dessert: A quenelle of chocolate sorbet resting on a thin, round chocolate cookie, in turn resting on a disk of rich chocolate ganache. Skinny decorative chocolate rods. Dratted gold foil on top.