The first course soup at lunch was creamy artichoke, sprinkled with pecans—good, as always.

The first course soup at lunch was creamy artichoke, sprinkled with pecans—good, as always.

Tuesday, 11 October, Kinderdijk, the Netherlands (windmills and cheesemaking!)

Written 21 March 2023

Pickled herring on the breakfast buffet this morning, rolled up with pickled onion inside! Yummy.

The closer we get to the Atlantic, the more commercial/industrial traffic we see on the river. We had no tour scheduled in the morning, so we just watched barge after barge after barge motoring by, mostly going upstream, and mostly empty. I counted and figured that the loaded barges carry ca. 70 containers each.

The first course soup at lunch was creamy artichoke, sprinkled with pecans—good, as always.

The first course soup at lunch was creamy artichoke, sprinkled with pecans—good, as always.

The main course was slow-roasted spiced pork belly with sweet corn mousseline. Wow, was that good! Tender, surprisingly lean, crispy on top, and deeply flavored. I'd like to learn to make that.

For dessert, I chose the pear tart Bourdaloue—pears embedded in a layer of almond-paste custard. Excellent.

For dessert, I chose the pear tart Bourdaloue—pears embedded in a layer of almond-paste custard. Excellent.

The other choice, shown at the right, was a "Monte Carlo," strawberry and pistachio ice creams, raspberry sauce, and a sheet of dark chocolate rolled into a sort of cigar.

In the afternoon, we were scheduled for windmills and cheese making. On the bus to Kinderdijk, where the windmills live, we passed this old water tower, masquerading as a medieval fortification. It's one of several dating from 1909, which are now private residences—one that we passed later in the day was pointed out to us especially—somebody bought it for 375,000 euros, then spent 270,000 euros to renovate it, and now lives there. Wonder if he installed an elevator . . . . This area doesn't bother with water towers any more. Since they're constantly pumping water anyway, they just use pumps to supply water pressure.

In the afternoon, we were scheduled for windmills and cheese making. On the bus to Kinderdijk, where the windmills live, we passed this old water tower, masquerading as a medieval fortification. It's one of several dating from 1909, which are now private residences—one that we passed later in the day was pointed out to us especially—somebody bought it for 375,000 euros, then spent 270,000 euros to renovate it, and now lives there. Wonder if he installed an elevator . . . . This area doesn't bother with water towers any more. Since they're constantly pumping water anyway, they just use pumps to supply water pressure.

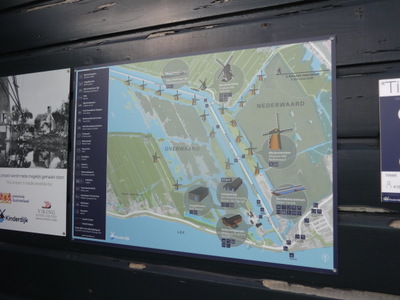

At the right here is a map of Kinderdijk, the worlds largest assemblage of working, vintage windmills and, since 1997, a UNESCO World Heritage site. We arrived on the road that runs horizontally along the bottom of the map. Our bus pulled into a lay-by (partly covered by the lowest of the gray circles), and from there, we made our way on foot to turn left into the little road to the right of the gray circle, then right across a little footbridge to the road that runs diagonally from bottom right to top left, where we turned left and walked as far as the second windmill on the right. That's the one that's been turned into a museum.

Kinderdijk, literally "child dike," got its name from a historical incident during which a cradle, complete with baby, was washed out of a house in time of flood and carried away. A cat was also aboard and managed to keep the cradle from capsizing, by hopping nimbly from side to side as necessary, until it washed up on this dike. The incident is commemorated in this life-size metal sculpture mounted to look as though it's floating, just next to the footbridge.

Kinderdijk, literally "child dike," got its name from a historical incident during which a cradle, complete with baby, was washed out of a house in time of flood and carried away. A cat was also aboard and managed to keep the cradle from capsizing, by hopping nimbly from side to side as necessary, until it washed up on this dike. The incident is commemorated in this life-size metal sculpture mounted to look as though it's floating, just next to the footbridge.

At the right is one of the lines of windmills, stretching away along the canal. As we strolled, I spotted a grebe and a pair of coots on the canals.

I'm embarrassed to admit how long it took me to realize that all those windmills that the Netherlands is famous for do not grind grain—they pump water! Kinderdijk is a particularly low spot. All the ground water in the region, if not the country, makes its way here, so this group of mills was built to deal with it—they are all in their original positions, not moved here to form a group like an open-air museum.

Here are a couple of them, closer up: a stone one with its canvas sails set at the left and a wooden one with bare sails at the right.

Here are a couple of them, closer up: a stone one with its canvas sails set at the left and a wooden one with bare sails at the right.

The dikes were started little by little. Back in 1550, to drain the land for farming, the locals dug two canals to drain water toward this lowest point, to a holding pond by the river. When the river was low enough, they could open a gate to drain the water into the river. That worked for a while, but eventually, the river never got low enough—if they opened the gate, river water flowed into the pond instead. That's when they built the first windmills, to move water into a holding basin high enough to drain into the river. They made that work for a while, but it was increasingly hard. The windmills we see now were built about 1740. Eventually, steam power arrived, which worked for another hundred years until electricity took over.

Today, the windmills at Kinderdijk still work and still pump water. They are all occupied as dwellings (except the one that's a museum), and their occupants ensure that they all get the 60,000 turns a year they need to stay in good working condition. Living in and operating a windmill makes you a miller, but these are all "voluntary millers." They have day jobs elsewhere and pump only in their spare time.

Here are two of the electric powered installations at Kinderdijk that now do the heavy lifting, by means of giant Archimedes screws, taking up the slack. These days, they would probably still have to operate regularly, even if all the windmills operated full time.

Here are two of the electric powered installations at Kinderdijk that now do the heavy lifting, by means of giant Archimedes screws, taking up the slack. These days, they would probably still have to operate regularly, even if all the windmills operated full time.

Remarkably, though, the mills have to operate in reverse, pumping water back in! The soil here is peat, and if it dries out sufficiently, they have trouble with settling and subsidence, so in very dry periods they have to pump water back in, to keep it high enough to keep the peat stable. They even had to water the dikes to keep them from drying out and cracking.

The guide told us that if all pumping stopped, though, Kinderdijk would be flooded in 3 months.

To become a miller at Kinderdijk, you need to start by getting a two-year degree in water management, then apprentice as an assistant miller. Then you can get on a waiting list. If a vacancy opens up, and you're next in line, you move in, pay rent to the foundation, and commit to pumping enough to keep the mill in good shape.

Some of the mills are occupied by families, some by single men, and one by a single woman. One of them houses a family that has lived there for 11 generations—they have special permission to pass it on to their descendents, so long as one of them qualifies to run it.

After Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans brought in consults from the Netherlands, acknowledged world masters of water management, who supervised construction. of a new levee and canal system that has helped with flooding problems there.

When the museum mill was still occupied, it housed a family with 11 children (a group photo hangs inside). The boys stayed home and apprenticed with their father to become millers. The girls were sent out to work for cash and only came home on weekends.

When the museum mill was still occupied, it housed a family with 11 children (a group photo hangs inside). The boys stayed home and apprenticed with their father to become millers. The girls were sent out to work for cash and only came home on weekends.

At the left, shelves of china, and at the right one of the larger rooms. On the far wall, you can see one of the enclosed "cabinet beds" of the day. A heavy curtain can be pulled across the opening at night for privacy and warmth. The living space was on three levels, and the rooms at the top ere pretty small.

Cooking was done in a little separate brick building, because of the danger of fire. Each windmill had two doors, on opposite sides, because the top of the windmill could be rotated to make the sails face the wind, and at any given time, the sails might block one door.

At the left here the guide demonstrates how the windmill is rotated. The mill is surrounded by a ring of little stone bollards, painted white. The wooden top level of each mill is attached to an inverted-triangle arrangement of wooden beams. You can see both the rotating cap of the mill and the widest part of the wooden triangle in the right-hand photo. (In that photo, you can also see a white sign saying "Anno 1738"; this is one of the oldest mills at the site.)

At the left here the guide demonstrates how the windmill is rotated. The mill is surrounded by a ring of little stone bollards, painted white. The wooden top level of each mill is attached to an inverted-triangle arrangement of wooden beams. You can see both the rotating cap of the mill and the widest part of the wooden triangle in the right-hand photo. (In that photo, you can also see a white sign saying "Anno 1738"; this is one of the oldest mills at the site.)

The miller chains the bottom end of the triangle to the nearest bollard in the direction away from the wind, then turns the large vertical windlass attached to it (the guide is gesturing to it; her hand is in front of one of the white handles of the windlass) to wind up the chain and drag the whole apparatus around to the desired position. The apparatus can be rotated freely 360

We were curious about the process of rigging the canvas on the sails, so the guide asked the miller next door to come rig one for us. His day job is managing the museum and keeping it's mill in working order, as well as the one he lives in.

We were curious about the process of rigging the canvas on the sails, so the guide asked the miller next door to come rig one for us. His day job is managing the museum and keeping it's mill in working order, as well as the one he lives in.

When the canvas is not rigged, it is twisted into a tight rope and lashed to one edge of the sail. To rig it, the miller climbed the sail like a ladder (while wearing wooden shoes!) to unlash one of the ropes halfway up, then climbed back down making sure the rope along the edge of the canvas was properly hooked into all the little cleats along the leading edge of the sail. At the bottom, he untwisted it back into a flat rectangle and tied it down to the edges at the bottom.

Once we'd had a chance to cluster around, feel the canvas, examine the attachement points, etc. (note the column of cleats running down the edge of the wooden part of the sail), he unhooked it, twisted the canvas back into a tight lengthwise coil, and climbed back up the sail to replace the fastenings. The whole operation of putting it up or taking it down took maybe three minutes. I thought the wooden shoes looked precarious, but he assured us they were the best kind for the task.

Once we'd had a chance to cluster around, feel the canvas, examine the attachement points, etc. (note the column of cleats running down the edge of the wooden part of the sail), he unhooked it, twisted the canvas back into a tight lengthwise coil, and climbed back up the sail to replace the fastenings. The whole operation of putting it up or taking it down took maybe three minutes. I thought the wooden shoes looked precarious, but he assured us they were the best kind for the task.

At one point, the guide told us that the single woman miller had walked by us during the tour, but she didn't say anything until after the lady had gone, because she doesn't like being pointed out. Later, though, among the large photos decorating the walls of the restroom in the visitor center, I spotted this one, which might well be of her, twisting canvas.

Half of the windmills at Kinderdijk (the ones on the side of the canal where we were) are stone, and the other half, across the canal from us, are wooden. Apparently the peat on that side is softer, and when they started building stone windmills, they leaned and sank, so they switched to wood, which is much lighter.

Other differences persist from the days when the two sides of the canal were under the control of different boards of directors. The mills on our side are round and use brown canvas on their sails. Those on the other side are octagonal and use white canvas. The ones on our side have individual little kitchen huts. Those on the other side share a single larger bakehouse. For a long while, some animosity existed between the two boards, but the two water districts have since been merged, and they get along just fine now.

Then it was time to board the buses to visit a cheese farm. On the way, the guide pointed out this row of houses sitting well below the road. When they were built, in 1860, they had a view across it to the river (which you can see at the upper left, partly blocked by the rearview mirror), but rivers silt up, so their "normal" water level rises, so dikes and levees have to be raised.

Then it was time to board the buses to visit a cheese farm. On the way, the guide pointed out this row of houses sitting well below the road. When they were built, in 1860, they had a view across it to the river (which you can see at the upper left, partly blocked by the rearview mirror), but rivers silt up, so their "normal" water level rises, so dikes and levees have to be raised.

Once we were out of town, it was obvious we were in dairy country, as the lush green fields were dotted with Holstein/Friesian cows. This photo doesn't really show now wet the area is. Ditches full of water ran along both sides of the road, and all the fields were divided up into rectangles only 100 to 200 yards on a side, not by hedges or fences, but by canals, also full of water.

Other things the guide told us on the bus ride:

Written 22 March 2023

Written 22 March 2023

As we pulled into the dooryard of the family-owned and -run dairy we were to visit, the first thing that struck me was the fruit trees, apples on the left, pears on the right. The trees were unpruned and sprawling, clearly not part of the commercial enterprise, just mixed in with other trees and supplying enough fruit for the family.

This is the dairy where we found ourselves, one of seven farms making cheese in the area. They make Gouda exclusively, but in a bewildering array of flavored varieties. They, and all the other locals, pronounce is to rhyme with "howda," and the initial consonant is not a hard "g" but a velar fricative, not a sound we use in English, a lot like the "ch" of Channuka or Challah

This is the dairy where we found ourselves, one of seven farms making cheese in the area. They make Gouda exclusively, but in a bewildering array of flavored varieties. They, and all the other locals, pronounce is to rhyme with "howda," and the initial consonant is not a hard "g" but a velar fricative, not a sound we use in English, a lot like the "ch" of Channuka or Challah

At the right here is the tank where each batch of cheese starts as milk (the previous evening's milking mixed with the current morning's milking, I'm pretty sure she said) and turns, with the addition of rennet (an enzyme derived from calves' stomachs, now also made synthetically), a proprietary bacterial culture, and a little heat, to curds. A stainless steel grid (visible near the forearm of the spectator in the pale hoodie) is then dragged through the mass of curd to cut it up into manageable cubes.

The tank was, of course, empty, clean, and dry at 4 pm, awaiting the following day's batch. I think she said they process about 1700 gallons a day. It takes about 10 lb of milk to make 1 lb of cheese.

At the left, the guide (a daughter of the family) holds one of the molds into which the curds are then scooped and drained. This one is for making 4-lb wheels of cheese. The lid fits down inside the cylindrical sides of the mold and has a taller cylinder sticking up from it. That's so that molds can be stacked on top of one another and placed in a press that pushes the lids down into the molds, expelling whey and pressing the curds tightly together. Partway through the pressing process, the molds are unstacked, the cheese are dumped out of them and turned over so that they will have the nice rounded shape on both sides. The exception is the reduced-fat cheese—they leave those the same side up for the whole pressing, so that the flat top of each cheese makes it instantly recognizable as low-fat. (They make a little butter from the cream they skim from the milk destined to become low-fat cheese.)

At the left, the guide (a daughter of the family) holds one of the molds into which the curds are then scooped and drained. This one is for making 4-lb wheels of cheese. The lid fits down inside the cylindrical sides of the mold and has a taller cylinder sticking up from it. That's so that molds can be stacked on top of one another and placed in a press that pushes the lids down into the molds, expelling whey and pressing the curds tightly together. Partway through the pressing process, the molds are unstacked, the cheese are dumped out of them and turned over so that they will have the nice rounded shape on both sides. The exception is the reduced-fat cheese—they leave those the same side up for the whole pressing, so that the flat top of each cheese makes it instantly recognizable as low-fat. (They make a little butter from the cream they skim from the milk destined to become low-fat cheese.)

After pressing, the incipient cheeses are loaded into large mesh racks like the one shown at the right and soaked in a brine solution. The cheeses are made round partly because a square shape would lead to over-salty corners, where the thin edges allowed more salt to penetrate. Larger cheeses are soaked longer than smaller ones, to allow enough salt to penetrate.

The ones in the rack here are 8 kg each, and they have been flavored with peppercorns, ginger, onion, and garlic (presumably added in the tank), which is why they look all speckly; they'll spend 2 days in brine. This dairy makes cheeses in sizes from 1 lb to 34 lb.

Once they are salty enough, the cheeses are moved to racks for aging and eventually for coating.

Once they are salty enough, the cheeses are moved to racks for aging and eventually for coating.

Some of these have been coated or are in the process. Different coating color indicates different flavors; for example, black is truffle, red is red pepper. The coating is not wax anymore; it's a thinner, more rigid, plastic-like coating, supposedly edible, that lets the cheese breath. It's sponged onto the cheeses and left to dry for a few days, then the cheeses are turned so that it can be sponged on the other side. This process is repeated every three days for three weeks.

"Ordinary" Gouda is aged 2 months—their best seller is 2-month-old plain Gouda—but it can be aged for 2 years or even 4 years. Gouda is also sometimes made with goat's or sheep's milk, but not on this farm. I think she said much of their production is sold to hotels.

After touring the cheese-making operation, we walked a few steps across the yard to the dairy barn, where our initial guide's father took over. In the left-hand photo is one of the Great Pyrenees dogs who live on the farm.

After touring the cheese-making operation, we walked a few steps across the yard to the dairy barn, where our initial guide's father took over. In the left-hand photo is one of the Great Pyrenees dogs who live on the farm.

The farm has 270 cows and 200 heifers (i.e., young virgin cows), and they have 160 cows in milk every day—that's a big dairy operation for the Netherlands. After giving birth to a calf, each cow produces, on average, 15 gallons of milk a day for four months, then less. After a year her milk production stops and she is bred again, by artificial insemination (they keep sperm in a freezer for the purpose). Gestation takes 9 months. During that time, the cow needs rest. She isn't milked and she's kept in the barn. To prevent inbreeding problems, they get their sperm from multiple sources and occasionally even from a white-headed Montbelliard for added diversity.

When the time for calving is near, the cows lie down, stand up, walk around, and generally fidget. About 90% of the time, they are able to deliver their calves on their own, but some need help from the farmer or the vet. Occasionally, a caesarian delivery is necessary. After about an hour, the calf is able to stand up. Cows ordinarily produce calves and milk for about 15 years; they have one who gave birth at age 17.

The calves stay with their mothers for only a couple of days before being moved to little huts (left) set aside for the purpose, where they are bottle fed (actually bucket fed, the buckets have nipples at the bottom). The mothers go back to the milking barn. I think he said a heiffer is bred for the first time at about 15 months of age.

The calves stay with their mothers for only a couple of days before being moved to little huts (left) set aside for the purpose, where they are bottle fed (actually bucket fed, the buckets have nipples at the bottom). The mothers go back to the milking barn. I think he said a heiffer is bred for the first time at about 15 months of age.

A the right is a curious (or perhaps hungry) calf who came to check us out.

The cattle here eat about 30% grass, 30% corn silage (the corn grown around here is for cattle feed, not human), hay, and the residue from sugar beets after the sugar is extracted. In the summer, they spend all their time, day and night, outside on the pastures (they allow 1 acre per cow), only getting supplementary feed when they come in to be milked. Part of the pasture area is opened for grazing, and on the rest, they cut the grass two or three times a season and dry it for winter hay.

The canal system presents unique problems. The cows spend the cold months of winter inside the barns, and when they are released into the pastures for the first time each spring, they frolic with delight, and several always fall off the edges of the fields into the canals. They don't drown, because the canals aren't that deep, but neither can they get back up the steep sides into the fields without help. So the farmer has to go around with a tractor, hauling them out. Calves have the same problem. They're weaned off milk and onto a little grain and hay in their huts, but when they are first released onto pastures to graze, they gambol and trot around naively and fall off the edges into the water, where they too must be hauled out by people or tractors. Cattle that have spent a lot of time in the barn also freak out the first couple of times they are rained on, attempting to flee and, of course, falling into the canals.

Farmers are required to maintain their canals. Every october, they must clean and dredge all the ditches, and pile the dirt on the sides. If any don't, the government does it for them, charges them for the service, and fines them for the trouble. The government also comes regularly to test for tuberculosis.

Our guide also emphasized the enormous amount of documentation, in addition to all the breeding records, necessary to prove that they are abiding by all regulations. They actually need an individual license for each cow.

Finally, we visited the farm's shop, where we could buy any of their cheeses, as well as all sorts of cheese-serving apparatus, dish towels, etc. (The farm is currently run by three generations; Grandma was in the gift shop; a young grandson will be the 7th generation of the family to work here). They had cut cheeses into tiny cubes for us to taste; some of the flavors we got to try were pesto, garlic with Italian herbs, fenugreek, stinging nettle, walnut, chimichurri(!), hot pepper, clover, dill, plain garlic, and mixed herbs. We also got to try the 2- and 4-year aged plain Gouda; those were great!

Then it was back to the buses once more and home to the ship for dinner. We started with, what else, Gouda soup. Neither the Thai red chicken curry nor the seared halibut with riesling sauce appealed to me, so I had one last ribeye steak off the always-available menu.

Then it was back to the buses once more and home to the ship for dinner. We started with, what else, Gouda soup. Neither the Thai red chicken curry nor the seared halibut with riesling sauce appealed to me, so I had one last ribeye steak off the always-available menu.

Dessert was moelleux aux chocolate, which Americans would call a chocolate lava cake, with vanilla bean ice cream. Yummy.

Previous entry List of Entries Next entry