During the night, we cast off, followed the North Sea Canal west from Amsterdam, turned right up the coast, then turned right twice more to sail south to Hoorn, where we found ourselves at breakfast time.

During the night, we cast off, followed the North Sea Canal west from Amsterdam, turned right up the coast, then turned right twice more to sail south to Hoorn, where we found ourselves at breakfast time.Tuesday, 28 March, Hoorn: walking tour, performance, and bulb growers

Written 17 April 2023

During the night, we cast off, followed the North Sea Canal west from Amsterdam, turned right up the coast, then turned right twice more to sail south to Hoorn, where we found ourselves at breakfast time.

During the night, we cast off, followed the North Sea Canal west from Amsterdam, turned right up the coast, then turned right twice more to sail south to Hoorn, where we found ourselves at breakfast time.

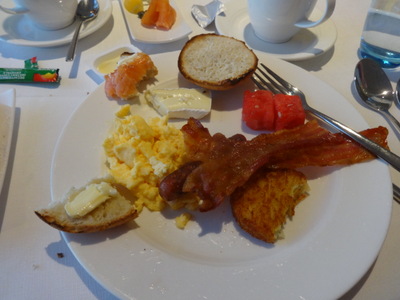

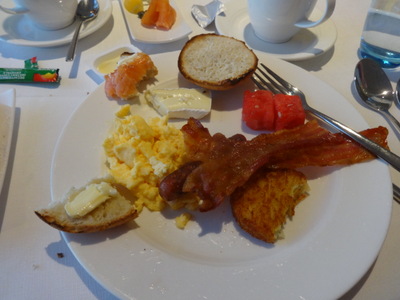

At the left here is a typical Viking breakfast for me. Scrambled eggs (Viking makes really good scrambled eggs), a crusty bread bun split and toasted, smoked salmon, cheese (alas, no more bucheron, just Brie), bacon, a hash-brown cake (the buffet had a different potato preparation each day), a little watermelon . . .

In addition, on this morning, a waiter brought around a tray of warm, flaky little cheddar and veggie quiches. Very tasty.

Now, once upon a time, the Netherlands had a more convex coastline and a large interior lake, but a series of really stormy seasons around the year 1200 tore out a large chunk of that coastline and opened the interior lake directly to the North Sea, creating the vast inlet known as the Zuider Zee. The country lost some farm land in the process, but the new arrangement had advantages: a huge herring fishery developed, and Amsterdam, which had been a good ways inland, was suddenly a North Sea port. The Zuider Zee was shallow and full of shifting sand bars, but without it, arguably, Amsterdam would never have become the global economic power it did, during its golden age in the 17th century.

But it also had one great disadvantage. People soon learned that having the notoriously turbulent North Sea at your doorstep meant that, during every big storm, it ended up in your lap. About 1916 the country got fed up with the constant floods and set about building a dike right across the mouth of the inlet, about 20 miles. I imagine they had to pause for a while during WWI, but it was finished in 1932. It has locks in it, so ships can pass through, and it's backed up by a second dike across the whole width of the old inlet.

Once the dike was in place, the area inside it was no longer tidal and was continually replenished with fresh water by the Rhine and by rainwater, so every day at low tide, they opened the locks and let water pour out into the North Sea. Then the locks were closed so that seawater couldn't flow back in at high tide. They do the same to this day, and as a result the area inside the dike is now a large freshwater lake, the Markermeer south of the second dike and the Ijsselmeer north of it. Amsterdam no longer floods, and parts of the lake floor have been diked, drained, and reclaimed as farm land. I think this story is the most astonishing thing I learned on the cruise.

But every omelet means broken eggs. Hoorn, which lies just south of the second dike, suffered a major economic decline. All those herring fishers, and the people who made the barrels to pack the herring in, and the ship builders, and all the other related occupations, lost their livelihoods. The hard times lasted until after WWII, when tourism began to fill the gap. Now, with modern transportation methods, it's less than an hour from Amsterdam, so enough people actually commute from there that trains run every 15 minutes at rush hour.

Parking for cruise ships in Hoorn is limited to "loading and unloading only," though, so after breakfast, everyone who was going on an excursion that day, morning or afternoon, was put ashore, and the ship immediately cast off and headed for Lelystad, at the other end of the second dike. No bus ride to reach the city center here—we were in it as we stepped off the ship.

Parking for cruise ships in Hoorn is limited to "loading and unloading only," though, so after breakfast, everyone who was going on an excursion that day, morning or afternoon, was put ashore, and the ship immediately cast off and headed for Lelystad, at the other end of the second dike. No bus ride to reach the city center here—we were in it as we stepped off the ship.

At the left here is an old guard tower, intended to protect the houses behind it, built by prosperous merchants during the city's heyday in the 17th century. Like all historic buildings in the Netherlands that no longer serve their original purposes, it's now a restaurant.

A few steps away was this handsome wooden sailing vessel, probably recreational. Note the rotating keel panels.

Facing us as we emerged from Freya, and too wide to fit in one photo, was the old prison, now a hotel. At the far right corner, its old chapel is now a cinema museum. Note the exuberate bank of daffodils across the front of it.

Facing us as we emerged from Freya, and too wide to fit in one photo, was the old prison, now a hotel. At the far right corner, its old chapel is now a cinema museum. Note the exuberate bank of daffodils across the front of it.

Our guide started by telling us the story of how the lake was formed. He said it's 300 miles around, and you can walk it in easy stages, along official hiking trails, stopping at bed-and-breakfast establishments along the way. It's a popular trip, and many walkers do it in about 10 days.

We were surprised to learn that members of local water-management boards are elected, and further that the elections are partisan—voters choose among a number of different water-management parties!

Only two commercial fishing boats still operate out of Hoorn, fishing for eels, which are about all that remain in the lake. Surprisingly, eel is still scarce and expensive, though popular. Blackheaded gulls were flying around the harbor—that's just a description, not a species name; I don't know what species they were. I also saw eared grebes diving among the boats.

The population of Hoorn is ca. 70,000. It got its name from the big bend in the coastline where it's located—it means both "horn" and "bend" in Dutch—and Cape Horn, at the southern tip of South America, is named for it (Dutch explorers from around here named it).

The population of Hoorn is ca. 70,000. It got its name from the big bend in the coastline where it's located—it means both "horn" and "bend" in Dutch—and Cape Horn, at the southern tip of South America, is named for it (Dutch explorers from around here named it).

The expanded bike basket shown at the left here is a frequent sight. Some are empty, like this one, for carrying groceries or other cargo, and others are fitted out as baby or child carriers.

Our guide pointed out the colored stickers on signposts, like these on the shaft of a no-parking sign, are route markers for the various walking trails, the modern equivalent of the bronze scallop shells pointing the way to Santiago de Compostela.

This door into the guard tower was where citizens had to come back in the day to pay their taxes. The inscription says something to the effect that God loves those who pay up.

This door into the guard tower was where citizens had to come back in the day to pay their taxes. The inscription says something to the effect that God loves those who pay up.

a few steps away, on the top of the sea wall that used to protect the town from tides, are these three bronze figures. They are characters from a 1924 Dutch adventure novel by Johan Fabricius, based on the published journal of sea captain Willem Bontekoe, who sailed from Hoorn to the East Indies in the 17th century and was shipwrecked there. He made it home and never sailed again. Fabricius told the story from the point of view of three fictional cabin boys on Bontekoe's ship, and this statue is labeled (in four languages) "The Shipboys of Bontekoe." Not everyone in town is pleased with it; some consider it kitsch.

At the left here is just a nice view back toward the tower from a little bridge across this marina. If you walked toward the tower, you would come to the river lake just beyond it, and if you turned right, you'd come to the pier where we got off the ship.

At the left here is just a nice view back toward the tower from a little bridge across this marina. If you walked toward the tower, you would come to the river lake just beyond it, and if you turned right, you'd come to the pier where we got off the ship.

The plaque at the right is one the guide pointed out to us. It comemmorates a pair of sisters lived in this house during WWII and, like their neighbors, were forced to house German military. They also hid Jews in their garden shed. Everyone supposes that the Nazis must have known about it but apparently let them get away with it.

I think the ornate little building at the left here was once the town hall. Today, it's a museum, but it's closed for long-term renovations. The statue in the center of the square, visible a the right-hand edge of the photo, is of Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587–1629), a native of Hoorn who was an officer in the Dutch East India Company, founded Batavia, and served two terms as its governor-general. As is the case with so many heros of so many nations, his methods are now considered too ruthless and in fact were considered pretty extreme even at the time. In 2012, the city therefore added an explanatory plaque to the base of the statue, detailing the controversy over his actions and listing some of the atrocities attributed to him.

I think the ornate little building at the left here was once the town hall. Today, it's a museum, but it's closed for long-term renovations. The statue in the center of the square, visible a the right-hand edge of the photo, is of Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587–1629), a native of Hoorn who was an officer in the Dutch East India Company, founded Batavia, and served two terms as its governor-general. As is the case with so many heros of so many nations, his methods are now considered too ruthless and in fact were considered pretty extreme even at the time. In 2012, the city therefore added an explanatory plaque to the base of the statue, detailing the controversy over his actions and listing some of the atrocities attributed to him.

Near the base of the statue is this round stone, called the blood stone, because it's where public executions were once held.

At the left here is a sort of edgewise view of the "Koepelkerk," the cupola church. It has a long and cumbersome official name, but everyone calls it the Koepelkerk. It's Roman Catholic and is still in use as a church, making it something of a rarity in the Netherlands, where 80% of old churches have been decommissioned and turned into something else. It was designed by the same architect as St. Nicholas in Amsterdam.

At the left here is a sort of edgewise view of the "Koepelkerk," the cupola church. It has a long and cumbersome official name, but everyone calls it the Koepelkerk. It's Roman Catholic and is still in use as a church, making it something of a rarity in the Netherlands, where 80% of old churches have been decommissioned and turned into something else. It was designed by the same architect as St. Nicholas in Amsterdam.

The monument at the right stands near its door and is about three feet high. It's a WWII memorial.

This tower is of the Grote Kerk, the great church; the right-hand photo is of its nave. I think we were told that services are still occasionally held there, but it's closed off, and we were only allowed to view it from a glassed-in area near the entrance. The rest of the building has been converted to a hotel called, are you ready?, The Heavens. I understand that the windows of some of the rooms overlook not the street but the nave. The hotel's restaurant is called The Saint.

This tower is of the Grote Kerk, the great church; the right-hand photo is of its nave. I think we were told that services are still occasionally held there, but it's closed off, and we were only allowed to view it from a glassed-in area near the entrance. The rest of the building has been converted to a hotel called, are you ready?, The Heavens. I understand that the windows of some of the rooms overlook not the street but the nave. The hotel's restaurant is called The Saint.

At the left here is a wonderfully whimsical piece of art. We couldn't find a label anywhere, but it's pretty clearly a Flying Dutchman.

At the left here is a wonderfully whimsical piece of art. We couldn't find a label anywhere, but it's pretty clearly a Flying Dutchman.

At the right is a gablestone dating from 1628 depicting a red rooster. Our guide said that the red rooster is the symbol of the fire brigade, so perhaps the original occupant of this house was a fire fighter.

Back when these houses were built, gablestones, mounted over doorways, were street addresses. You told somebody that you lived in such-and-such a street, at the red rooster or the golden mermaid or some such. It was Napoleon, who conquered the Netherlands and was in charge here for a while, who wouldn't put up with anything that disorganized. He wanted to collect taxes systemtically and efficiently, so he decreed that henceforth everybody had to have a last name and a numbered street address. So there. Even after Napoleon left, the Dutch stuck with the practice and even based their modern system of law on the Napoleonic code.

As we learned on our two previous visits to Belgium, it was long the practice in this part of the world for communities of nuns to take in older women—and not necessarily the indigent—and to shelter them in quiet retirement. Here's a Dutch example. The inscription over the door says "The Old Women's House." We had several pointed out to us around town. I think this is the one that's now the public library.

As we learned on our two previous visits to Belgium, it was long the practice in this part of the world for communities of nuns to take in older women—and not necessarily the indigent—and to shelter them in quiet retirement. Here's a Dutch example. The inscription over the door says "The Old Women's House." We had several pointed out to us around town. I think this is the one that's now the public library.

The splendid edifice at the right was originally a monastery but is now (or at least was) Town Hall. I'm not sure whether there's a more modern structure elsewhere that now carries out that function.

Yet another (former) church façade—you just can't get far enough away from these churches to get all of the building into the shot—the east church ("Oosterkerk"). It still occasionally houses religious services but mostly it's a performance venue, and we had been promised a performance as part of our tour. We were greeted at the door with glasses of orange juice and mimosas, and to our delight the local performing group was the shanty choir of which the previous evening's entertainment had been just a traveling squad! Same salmon-colored jeans, but different tops, reading "Hoorn Shanry Choir" rather than "shanty men." And twice as many of them, with two accordions!

Yet another (former) church façade—you just can't get far enough away from these churches to get all of the building into the shot—the east church ("Oosterkerk"). It still occasionally houses religious services but mostly it's a performance venue, and we had been promised a performance as part of our tour. We were greeted at the door with glasses of orange juice and mimosas, and to our delight the local performing group was the shanty choir of which the previous evening's entertainment had been just a traveling squad! Same salmon-colored jeans, but different tops, reading "Hoorn Shanry Choir" rather than "shanty men." And twice as many of them, with two accordions!

Again, they were fabulously good, singing traditional shanties in both Dutch and English (and one in French) and even some more modern stuff like Sloop John B. David was really, really sorry he missed them earlier.

After the performance, on our walk to the parking lot where buses waited to take us to lunch, we passed this beautiful converted barge. Clearly now a home, but probably also still mobile.

After the performance, on our walk to the parking lot where buses waited to take us to lunch, we passed this beautiful converted barge. Clearly now a home, but probably also still mobile.

Contrast this row of houseboats on the far side of the harbor. They were certainly never actual boats, just houses built on floats. Still a cool place to live, though.

At the left here is an old city gate, left free standing, like all the others when the walls were torn down to make way for ring roads. The entrance through it is a little crooked so you couldn't shoot through it with a cannon. The little house on top is now a private residence.

At the left here is an old city gate, left free standing, like all the others when the walls were torn down to make way for ring roads. The entrance through it is a little crooked so you couldn't shoot through it with a cannon. The little house on top is now a private residence.

At at the right, a beech hedge. we saw them everywhere on this trip, and I was rather suprised at the concept. First, a deciduous hedge? And, second, why beech? They make such majestic trees, yet we saw few of them left to grow that way. Maybe beech was chosen because of the extremely dense, stiff, twiggy nature of their growth when trimmed into hedges. The leaves might be gone, but the bare wood is still a formidable barrier.

Other things the guide told us:In and around Hoorn, I spotted jackdaws, mallards, black-headed gulls, Nile/Egyptian geese, Canada geese, magpies, greylag geese, eared grebes, and a black and white saddleback duck (a scaup maybe?).

The ride to lunch was only about 10 minutes, and the venue was a Van der Valk hotel—actually a hotel complex (part of a chain), complete with "Jack's Casino" and a vast restaurant with an extensive buffet of Dutch food. The "Jack" turns out to be Captain Jack Sparrow, of Pirates of the Caribbean, so the men's room door features a life-size portrait of him swashbuckling away. The ladies' room has a similar portrait of Keira Knightley.

That explains why a restaurant described to us as providing a "typically Dutch lunch" should be toucan-themed (you can buy a T-shirt saying "If I can, you toucan!" and why the dining room is decorated with slightly lopsided stuffed parrots.

The buffet was good. At the left, part of the fruit selection, which was accompanied by big bowls of sauces and yogurts. At the right, the cheese and cold cuts (the last three, farthest from the camera, were pickled herring, smoked salmon, and beef carpaccio—yum!).

The buffet was good. At the left, part of the fruit selection, which was accompanied by big bowls of sauces and yogurts. At the right, the cheese and cold cuts (the last three, farthest from the camera, were pickled herring, smoked salmon, and beef carpaccio—yum!).

On the other side the oval station displaying the cold cuts were many prepared salads—egg, salmon, tuna, herring, potato, tomato, marinated cucumber, artichoke, niçoise, Greek, etc.

On the wall beyond that were the hot items. Because Dutch food is heavily influenced by Indonesian (the way British food is heavily influenced by Indian), the items included, beyond bitterballen, frikadeller, fries, etc., skewers of chicken saté in spicy peanut sauce, crisp vegetable spring rolls, and such.

On the wall beyond that were the hot items. Because Dutch food is heavily influenced by Indonesian (the way British food is heavily influenced by Indian), the items included, beyond bitterballen, frikadeller, fries, etc., skewers of chicken saté in spicy peanut sauce, crisp vegetable spring rolls, and such.

On the opposite wall was the huge selection of breads and rolls, inluding all the French Viennoiseries (pain au chocolate, pain au raisins, croissants), and different flavors of butter, margarine, jam, Nutella, etc.

The desserts ran heavily to sweet breads with raisins and cinnamon. The photo at the right shows the last piece or two of the most popular item, a round raisin bread with a thick layer of cinnamon paste running through the center.

We each got a token good for one alcoholic drink, and more could be purchased. Soft drinks and juices were free ad lib.

After lunch, in the lobby, waiting for the buses, I got this shot of the portraits of the two Van der Valk brothers. Then as I rejoined the group of other passengers, a guy walked by, out the door, carrying a flat cardboard box with an unmistakable color scheme. Wait, what?! I looked around the other side of the lobby's large central staircase, and there it was—yes, right there in the lobby of a Dutch hotel complex—a Dunkin' Donuts. Easter was approaching, so the donuts were even more elaborately decorated than usual. Some of them, you couldn't see for the neon-colored frosting. Some were dressed up as Muppet characters, others as frogs or Eastern bunnies or nests full of Easter eggs. A sight to behold!

After lunch, in the lobby, waiting for the buses, I got this shot of the portraits of the two Van der Valk brothers. Then as I rejoined the group of other passengers, a guy walked by, out the door, carrying a flat cardboard box with an unmistakable color scheme. Wait, what?! I looked around the other side of the lobby's large central staircase, and there it was—yes, right there in the lobby of a Dutch hotel complex—a Dunkin' Donuts. Easter was approaching, so the donuts were even more elaborately decorated than usual. Some of them, you couldn't see for the neon-colored frosting. Some were dressed up as Muppet characters, others as frogs or Eastern bunnies or nests full of Easter eggs. A sight to behold!

Out front, when the buses pulled up, we were sorted into two groups. Most boarded buses headed back to the ship, but David and I and a couple of dozen other enthusiasts were all put on the bus a small, family-owned tulip-bulb farm. Happily, most the the tour was sheltered (if not exactly indoors), because it was cold and windy out there!

Out front, when the buses pulled up, we were sorted into two groups. Most boarded buses headed back to the ship, but David and I and a couple of dozen other enthusiasts were all put on the bus a small, family-owned tulip-bulb farm. Happily, most the the tour was sheltered (if not exactly indoors), because it was cold and windy out there!

On the way there, I saw a few sheep and goats in the fields, and the roadsides and medians were masses of blooming daffodils, hyacinths, and crocuses.

The farm we visited is called "Mr. Tulip," and our guide, the son of the family, was a towering young man wearing wooden shoes painted with a maniacally smiling "Mr. Tulip" image. We've learned that the Netherlands is the tallest country in the world, on average, and this guy was certainly evidence.

It's a family business, in its fourth generation. They started with a combination of vegetables and flower bulbs. The second generation cut out potatoes and specialized only in certain veggies and more flower bulbs. The business now produces 20 million tulip bulbs a year (of 15 varieties); that's a small-scale operation around here, even though they sell bulbs all around the world.

First, we went into the warehouse area, one corner of which was also the gift shop, where a few flats of blooming tulips were set out. All the buildings were pretty much at outdoor ambient temperature, but at least we were out of the wind and the rain. The blooming tulips were just for demonstration purposes. The photo at the right shows the view down into the flat, revealing that each bulb is simply set into a well in a plastic frame and grown hydroponically—no soil involved.

But that's not what they do here at Mr. Tulip. They are tulip bulb farmers—they produce the tulip bulbs that other businesses then grow up (in this hydroponic way) to produce tulips for cut flowers.

To produce a nice fat tulip bulb that will predictably produce a nice big tulip flower (strictly one to a bulb), you start with a small tulip bulblet (which you have prechilled or otherwise primed) and plant it out in the field. It will grow up and produce a tulip bud, which you, as a bulb farmer, will—just at the height of flowering—come by with a specially designed mower and ruthlessly cut off, just below the flower, leaving as much of the green plant intact as possible. The flowers fall to the ground to be mulched back into the soil. You then lovingly tend and nurture the green plant for the rest of the season, while it photosynthesizes and, for want of other outlet, pours all its output into the bulb below, swelling it up in preparation for trying again next season to produce a successful flower. At the end of the season, when the plant withers, you pull up the bulb, which will be much larger than when it was planted, dust it off, peel it, break off all the little bulblets it will have produced around the edges (and set them aside for next season's planting), and add the large main bulb to the growing heap of others in big wooden bins. They will be sold in bulk to other businesses, which will grow them up hydroponically to produce cut tulip flowers.

Some bulb growers package part of their output for retail sale to home gardeners, but Mr. Tulip doesn't.

To grow their 20 million bulbs, they use about 18 acres of land, being careful about the depth of planting and the density at which to plant. Because you can't grow tulips over and over in the same field (they're heavy feeders and accumulate pests), they swap land in rotation with neighboring dairy or vegetable farmers, so as to grow tulips on the same land only about every seven years. They can't exchange land with onion or garlic farmers, because those species have the same pests as tulips. They test before planing for pests and for nutrients so they know how much fertilizer is needed; it varies with how recently the cows have been there to make their contribution.

The planting and harvesting are automated, of course, and an amazing innovation has recently facilitated the latter. As the bulbs are planted, they are sandwiched between two layers of netting (nylon, I think; synthetic anyway) with soil on top. The roots grow down and the flowers up, right through the netting, without difficulty. After two weeks in the field for rooting, then three more for flower production, it's time for the flower cutting, as descriped above.

The planting and harvesting are automated, of course, and an amazing innovation has recently facilitated the latter. As the bulbs are planted, they are sandwiched between two layers of netting (nylon, I think; synthetic anyway) with soil on top. The roots grow down and the flowers up, right through the netting, without difficulty. After two weeks in the field for rooting, then three more for flower production, it's time for the flower cutting, as descriped above.

At harvest time, the machinery in the photo at the right scoops up both layers of netting, peels them apart onto separate rollers, and drops the bulbs in between onto a conveyer that dumps them into big wooden boxes (maybe a meter on a side) at the back. One person drives the tractor (the green part) pulling the harvester (the larger pink part), a second person operates the harvester, and a third follows along behind in a truck with a forklift, changing out the wooden boxes as they fill.

The harvester (and several other essential tulip-growing machines, like planters and flower cutters ) was developed and is manufactured by a company called Pink Innovation; that's why it's so entirely pink. It's only used for a small fraction of the year, so Mr. Tulip shares it with two other farms. It can do up to 10 acres a day. They try to havest on a dry day, so that less soil sticks to the bulbs.

The rolls of dirty netting are sent off to a business that just cleans dirty tulip netting, so that they can be used again for the next planting cycle. Mr. Tulips nets are 1.8 m wide, but some farms are going over to 2.5 m rolls.

Only five people work here right now, but at harvest time, they hire on up to 20 more, some of whom live in little prefab huts they've installed for the purpose. They work 7 days a week. All the peeling and separating of bulbs still has to be done by hand, and sometimes cleaning is needed as well. Bulbs for export need to meet the standards of the receiving country, which vary widely. The US and Australia are the strictest, especially because of concerns about soil-borne pests, so bulbs intended to go there have to be cleaned thoroughly and sterilized (at least they don't have to be treated with methyl bromide anymore; that's nasty stuff). And he said something about import of DNA only being permitted for use in government facilities, but I didn't catch the details on that one.

While the tulips are blooming in the fields, they watch for oddballs—flowers with atypical color as a result of mutation or viral infection—and mostly just weed them out, but if they see something really special, they may try to reproduce it. About 200 to 300 varieties of tulip are widely commercially used, and no, there are still no truly blue or truly black ones.

Back in the warehouse, our guide asked if we would like a bouquet of tulips to take back to the ship. Of course we would, but the first time he twitched a blooming tulip out of its hydroponic crate and casually snapped the bulb off, all the gardeners in the group gasped and flinched. He did it a couple dozen more times and and handed us a lovely bunch of buds just ready to burst into bloom in a variety of colors. They graced the reception desk for the rest of the cruise.

At this point, the ship was in Lelystad, on the other side of the lake, so to get there we had to drive northeast from Mr. Tulip around to north side of Hoorn, out onto the peninsula northeast of it, and across (i.e., along) the 29-km second dike, with the Markermeer on our right and the Ijsselmeer on our left. On our way to the near end of the dike, we passed quite a few swans, just hanging out in the fields and pastures.

At this point, the ship was in Lelystad, on the other side of the lake, so to get there we had to drive northeast from Mr. Tulip around to north side of Hoorn, out onto the peninsula northeast of it, and across (i.e., along) the 29-km second dike, with the Markermeer on our right and the Ijsselmeer on our left. On our way to the near end of the dike, we passed quite a few swans, just hanging out in the fields and pastures.

We also passed several of these old-fashioned pyramidal farm houses. The guide pointed them out particularly. Each was built to surround a huge, pyramidal haystack. In the winter, the people and the livestock all lived inside, and the haystack fed the livestock. I didn't see how the haystack was conveniently replenished in the summer—did they open a section of the thatched roof?—but the guide didn't address that point.

He did remark that, in the eastern part of the country, you might see villages wth the town hall, church, and shops clustered around a central square, but here, the villages are strung out along the roads.

Ahead of the bus here, you can see the road dip down to pass under a canal.

Ahead of the bus here, you can see the road dip down to pass under a canal.

Then, a short while later, we were on the dike, crossing the great freshwater lake. Besides all the usual birds, I spotted a great egret. And cormorants, of course; always cormorants.

At the other end of the dike, we arrived in Lelystad, where the bus driver seemed a little at a loss to find the ship. On the way through town, we passed what looked a lot like an old city gate, flanked, I'm afraid, by a Dunkin' Donuts and a Subway.

At the other end of the dike, we arrived in Lelystad, where the bus driver seemed a little at a loss to find the ship. On the way through town, we passed what looked a lot like an old city gate, flanked, I'm afraid, by a Dunkin' Donuts and a Subway.

As we finally arrived at the cruise-ship docking zone, I admired the Monarch Princess, but I absolutely cracked up when I looked at the next berth over and saw her sister ship, the Monarch Governess! I guess aboard that ship, if you don't eat all your vegetables, you can't go on the next day's excursion!

In the end, although we had to walk a good ways in the rain, we found our ship. In the lobby, we were met by the concierge's staff bearing trays of chocolate-dipped strawberries. Nice.

In the end, although we had to walk a good ways in the rain, we found our ship. In the lobby, we were met by the concierge's staff bearing trays of chocolate-dipped strawberries. Nice.

As soon as we were aboard, the ship cast off and headed toward our next port of call. The photo at the right shows a particularly handsome little ship we passed on the way out of the harbor.

During the evening briefing, Program Director Dominic told us a little about Rotterdam. We'd heard several times that it was the second largest port in the world "after Asia." Well what that means is that nine ports in China are each larger than Rotterdam. They should say "the largest port outside Asia"!

We also learned that Rotterdam is a showcase of modern architecture. Because of its tactical and strategic importance, it was bombed to smithereens during WWII. Many towns chose to reconstruct according to their old architectural styles, but Rotterdam made the decision to go all modern all the time, and the results are spectacular.

We started dinner with this baked crab cake with scallion remoulade. David didn't cre for it, but I liked it a lot.

We started dinner with this baked crab cake with scallion remoulade. David didn't cre for it, but I liked it a lot.

Then he chose the braised beef ragout.

I went instead for the seared cod with vegetables and chanterelle mushrooms.

I went instead for the seared cod with vegetables and chanterelle mushrooms.

We both had the carrot cake with cream cheese frosting for dessert. Sure, it's pretty American, but it was actually very good carrot cake.

Previous entry List of Entries Next entry