South Limburg has about 450 limestone quarries, from small to very large, but most are no longer in use. Limestone is now quarried only for restoration work, and it's expensive.

Here's another view of the Jeker. You can just see it foaming through the water gate in an old section of town wall, farthest from the camera, an indication that it really is running high, despite its calm appearance elsewhere. The gate could be closed in case of attack. The guide told us the river had been "replaced" (rerouted, maybe, to suit the millers' convenience?).

Here's another view of the Jeker. You can just see it foaming through the water gate in an old section of town wall, farthest from the camera, an indication that it really is running high, despite its calm appearance elsewhere. The gate could be closed in case of attack. The guide told us the river had been "replaced" (rerouted, maybe, to suit the millers' convenience?).

Near a little chapel that used to be part of a monastery but is now the city's natural-history museum, we walked past the monastery's gardens. I leaned over the low wall to snap this shot of a particularly pretty plant, sprinkled with sparkling rain drops (it was drizzling), and only later did I notice the handsome snail and cute ladybug captured in the same frame. The plant, I am reliably informed by the app "Picture This," is Corydalis scouleri, Scouler's fumewort.

When the monastery was still active, the sisters took care of psychiatric patients there. Now, as a museum, it includes a glass house that encloses large fossils from the time when this area was a shallow sea.

Regular readers will know my habit of photographing (and often of riding on) little touristy sight-seeing trains. Coming along the street toward us (left) and passing by (right), looking like nothing so much as a bus-stop shelter on wheels, is the local "little white train." We didn't get to ride one this trip, as we were continously in the hands of knowledgeable local guides, either on foot or in bigger buses.

Regular readers will know my habit of photographing (and often of riding on) little touristy sight-seeing trains. Coming along the street toward us (left) and passing by (right), looking like nothing so much as a bus-stop shelter on wheels, is the local "little white train." We didn't get to ride one this trip, as we were continously in the hands of knowledgeable local guides, either on foot or in bigger buses.

Here, at last, is Vrijthof Square, the vast central square we had heard about. We crossed it about in the middle, so there's as much of it behind me as appears in the photo.

Here, at last, is Vrijthof Square, the vast central square we had heard about. We crossed it about in the middle, so there's as much of it behind me as appears in the photo.

It will soon be green and shaded, once the knobbly pollarded plane trees leaf out. The big brown building in the center of the shot is the back of St. Servatius, and the red tower to the left of it is St. John.

The right-hand photo shows a ceramic plaque commemorating the 300th anniversary (in 2017) of the time Peter the Great (of Russia) spent here. I know I wrote up the story of Peter's travels abroad to study boat building, somewhere in my 2017 travel diary, but I can't immediately find it. I have got to find time to index these diaries!

The Sunday morning church bells were ringing as we made our way back to the ship for Sunday lunch.

The Sunday morning church bells were ringing as we made our way back to the ship for Sunday lunch.

I paused to photograph these four memory stones set in the sidewalk, parents and two sons judging by the dates of birth. All four died at Auschwitz. The younger son lived a few months longer than the others, who all died the same day—he must have been the better laborer.

Once we got back to the ship, we had to pass through a Tauck ship to get aboard. The photo at the right shows part of its central staircase. Aboard its vessels, Viking uses a decor that a friend of ours once called (referring to our house, actually) as "Scandinavian bleak." Tauck apparently goes for opulence.

Lunch was underwhelming. The fine-print appetizers were actually pretty good—a mixed seafood salad and actual vitello tonnato—cold roast veal with tuna sauce, an Italian classic—made with the left-over roast veal from the previous night.

Lunch was underwhelming. The fine-print appetizers were actually pretty good—a mixed seafood salad and actual vitello tonnato—cold roast veal with tuna sauce, an Italian classic—made with the left-over roast veal from the previous night.

The first course was beef barley soup with root vegetables. Pretty good. But the main courses were without much interest. I had the baby back ribs, which were only so-so. David just got the cheeseburger from the always-available menu, which he said was also so-so. I think David had the vanilla panna cotta with raspberry sauce—he thinks Viking panna cottas aren't firm enough—and I had a "creole," rum-raisin ice cream, rum-marinated pineapple, coconut, and banana.

[Unfortunately, in the process of photographing the first course, I dropped my camera into my bowl of beef and barley soup (cue use of uncharacteristic language), but I dried it off, and it kept working, though it took me a while to figure out now to restore the settings that got changed as I scrubbed it all over with my napkin. During the afternoon, the edges of the screen fogged up a little, so some moisture must have gotten inside. Overnight, I left my computer charger plugged in and set the camera on top of the transformer brick, which gets warm. Fortunately, that cleared up the fogging problem.]

Then it was back into the buses for our tour of Charlemagne's cathedral and treasury in Aachen, Germany. As we pulled away, the ship cast off behind us, headed for our afternoon rendez-vous point in Gellik, Belgium.

Then it was back into the buses for our tour of Charlemagne's cathedral and treasury in Aachen, Germany. As we pulled away, the ship cast off behind us, headed for our afternoon rendez-vous point in Gellik, Belgium.

The photo at the left (through the bus window) is of the Hoge Brug, the High Bridge, over the Maas. It was designed and built just for pedestrians and bicycles.

At the right is a view (also through the bus window) of the American WWII cemetery. An option for the afternoon was a four-hour tour of just that, but we chose Charlemagne over it. Since we had to drive right by it to get to Aachen, though, we made a little detour to get at least a quick look at it. The 40,000 graves that used to be here are now down to 8,000 because so many families decided to bring their sons back for reburial at home. This has been true of many of the war cemeteries we have visited, and yet, the graves are always grouped compactly, in neat, unbroken rows. I can't help but wonder how they manage that—move a grave from the back to fill the gap whenever one from the front is removed?

Aachen, I was surprised to learn, is called Aix-la-Chapelle in French (and Aken in Dutch). It is, in fact, the Aix to which the unnamed rider foundered his horse Roland in bringing the good news from Ghent in the poem by Robert Browning! Who knew?

My first impression of Charlemagne's cathedral was dominated by the two absolutely magnificent Japanese magnolias that flank its door. They were in the fullest bloom possible, and I've never seen finer specimens. I'm sure Charlemagne (747–814 AD) never saw them, but they are an excellent addition.

My first impression of Charlemagne's cathedral was dominated by the two absolutely magnificent Japanese magnolias that flank its door. They were in the fullest bloom possible, and I've never seen finer specimens. I'm sure Charlemagne (747–814 AD) never saw them, but they are an excellent addition.

Charlemagne is recognized as the first ruler to unite all of northwestern Europe, and eventually Italy as well, since the western Roman Empire fell apart a few hundred years earlier (that's when all the Roman cities in this area, dating from around the birth of Christ, shrank or were abandoned, ca. 400 AD, when the empire could no longer support them as it had; Aachen was one of them). He's therefore considered the founding father of the Holy Roman Empire (which lasted 1000 years) and of both France and Germany!

Like all the kings and emperors of his day (and for a long time after his day), Charlemagne traveled constantly to hold his empire together, but toward the end of his life, he got tired and decided to settle down, and he chose Aachen as the place to do it. He therefore founded a religious chapter there and built them a cathedral, with the idea that their principal activity would be to pray for his soul. He was buried in the church when he died in 814, and for hundreds of years afterward, Aachen was a place of pilgrimage as important as Santiago de Compostela.

The building he commissioned was relatively small and has been added onto frequently since his death. A fortuitous effect of all the accretions is that, when the cathedral was bombed in WWII, the outer portions were badly damaged but their existence shielded the inner core, preserving Charlemagne's original portions almost intact.

In the days of Charlemagne, Aachen may have been only 2000 people, less than in Roman times, but as an emperor, he still commanded world-wide respect. He sent emissaries as far as Bagdad (population of maybe a million) to present gifts to other rulers. The party from Bagdad took years to get back again, but they brought a return gift—a live elephant!/p>

When Charlemagne was born, he father (Pepin the Short) had not yet become king—he was technically a vassel of a nominal king who had no power. Eventually, Pepin dethroned him and took over as ruler. At that point, Charlemagne came to be the soneof the king and in time inherited the thone. He was married at least four times, maybe five, and had illegitimate sons. He outlived only one legitimate son (Louis the Pious) and left the empire to him in in 814. Louis's sons then divided Charlemagne's empire into what would become Germany on one side and France on the other. I wrote about that process in my 2019 travel diary (I think the division took place in Koblenz), but again I haven't taken the time to look up the entry.

The (actual nordic) Vikings showed up in the 880's and started plundering, but that's another story entirely.

Inside the cathedral, the local city guide (to whom our program director had turned us over) turned us over to the cathedral's offical guide. We started by climbing to second-floor level.

Inside the cathedral, the local city guide (to whom our program director had turned us over) turned us over to the cathedral's offical guide. We started by climbing to second-floor level.

These two photos are of surviving sections of the mosaic floor of the second-floor gallery. Only small fragments survive from Charlemagne's time.

At the left here is a view up into the dome of the central part of the church, the part dating from Charlemagne's time. At the right is the view down into the lower level of the central part. We were standing on the second-floor gallery that runs around the sides of it. We were warned not to lean on the bronze railing we had to look over to see the lower section, because it does date from Charlemagne's time and might be a little fragile. Back in the day, it and all the other bronze fittings would have been polished to gleam like gold. The gallery where we stood was the local parish church, with its own altar and baptismal font, whereas the lower level was the "collegiate" church used by the priests of the chapter. It also serves as the cathedral for the diocese of Aachen. The guide described it as "also the episcopal [meaning "of the bishop"] church of the diocese," causing momentary confusion in those who took the word to refer to the protestant denomination. Each of the priests in the chapter, and there were lots, had to say mass several times a day, so the building housed more than 30 altars, all of which were kept busy. Today, at least two services a day take place here; they are always in the morning so that tours can be conducted in the afternoon.

At the left here is a view up into the dome of the central part of the church, the part dating from Charlemagne's time. At the right is the view down into the lower level of the central part. We were standing on the second-floor gallery that runs around the sides of it. We were warned not to lean on the bronze railing we had to look over to see the lower section, because it does date from Charlemagne's time and might be a little fragile. Back in the day, it and all the other bronze fittings would have been polished to gleam like gold. The gallery where we stood was the local parish church, with its own altar and baptismal font, whereas the lower level was the "collegiate" church used by the priests of the chapter. It also serves as the cathedral for the diocese of Aachen. The guide described it as "also the episcopal [meaning "of the bishop"] church of the diocese," causing momentary confusion in those who took the word to refer to the protestant denomination. Each of the priests in the chapter, and there were lots, had to say mass several times a day, so the building housed more than 30 altars, all of which were kept busy. Today, at least two services a day take place here; they are always in the morning so that tours can be conducted in the afternoon.

This central area, plus the lower part of the steeple are the only parts that Charlemagne himself commissioned. No one knows how the interior was decorated when it was first built. It may simply have been white. The gorgeous mosaics and the marble were added much later. The columns in the arches, though, are original. Charlemagne brought them, and other ornaments from antiquity, over the alps to demonstrate continuity with the emperors of ancient Rome. They serve no structural purpose. During the time when the city was occupied by the French, the columns were removed and taken to Paris. In the 19th century, Aachen got the right to get them back, but some were fixed in place in Paris and couldn't be moved; those are now represented by copies.

The central church is an octagon surrounded by a 16-sided deambulatory. The number eight represents the seven days of the creation, plus the sabbath, and therefore fulfillment and harmony.

The mosaics were designed by two different artists. Jean-Baptiste de Béthune from Belgium designed those in the dome, whereas Hermann Schaper, a German, designed the lower ones. They were actually made elsewhere (some in Italy), then brought here for assembly and installation. In upper part of the dome, 24 kings (12 from before Christ and 12 from after) bring their crowns to Jesus. At the end of time, all their power would cease, so that's why they brought there crowns to christ. In the small image here, it looks like more than 24, because each is holding his crown up in front of him at head height, with robes hanging down from his arms, so it looks like 48 heads. Christ, in a red robe, is at 6 o'clock in the photo, and the kings are queuing left and right to approach him.

The larger figures in the lower dome include Mary, John the Baptist, the angel Gabriel, some other angel whose label I can't read, Paul, Peter, Philip, and presumably the rest of the apostles—that would make 16, right?

At the left here is a better view of the lower part of the dome, showing the columns in the arches and Schaper's mosaics behind them.

At the left here is a better view of the lower part of the dome, showing the columns in the arches and Schaper's mosaics behind them.

At the right is one of those mosaics on the side of the gallery where we stood. Gorgeous. Notice all the acanthus leaves in the pattern (as well as in the capitals of the columns). Acanthus is apparently a symbol of eternal life.

At the right, still at second floor level where we stood, is Charlemagne's throne, facing out over the railing overlooking the church below. As you can see, it's pretty rudimentary and downright tatty compared with all the gilding elsewhere. It's made of flat slabs of whitish stone bolted together with metal angle-irons. The slabs were clearly scavenged, as one of them on the far side is actually engraved with the grid for an ancient board game now called "nine men's morris." Clearly these stone slabs had some historical or mystical importance to Charlemagne, and since he revered them, generations afterward have continued to do so.

At the right, still at second floor level where we stood, is Charlemagne's throne, facing out over the railing overlooking the church below. As you can see, it's pretty rudimentary and downright tatty compared with all the gilding elsewhere. It's made of flat slabs of whitish stone bolted together with metal angle-irons. The slabs were clearly scavenged, as one of them on the far side is actually engraved with the grid for an ancient board game now called "nine men's morris." Clearly these stone slabs had some historical or mystical importance to Charlemagne, and since he revered them, generations afterward have continued to do so.

Charlemagne himself was not crowned here—that happened long before the church was built—but his successors all were. They were crowned in the church downstairs, then climbed to the gallery and sat on this throne while the Lord's prayer was recited, then continued elsewhere for the rest of the ceremony.

"Now," our guide told us, "we make a journey of 600 years in two or three minutes," walking downstairs and into the choir hall. Because the original church was just octagonal, it didn't have the traditional "choir" space (between the trancept and the apse) of cruciform churches, so a large "choir hall" was added later, as were side chapels around the sides of the original octagon. The choir hall, shown in the right-hand photo, is nicknamed "the glass house of Aachen" because Gothic architecture allowed it to make so much of the wall space into windows, each of which is 26 m high. Each double circle in the abstract windows echos the number 8, and two silver rectangles echo the reliquaries below.

None of the windows survived the war—they were all blown out, so the ones you see here are modern. In the photo, you can also see two large golden reliquaries in glass cases (one at the lower right edge of the image, the other in the distance), as well as a large golden "starburst" suspended from the ceiling. The reliquaries are not actually gold; they were clad in silver, then "fire-gilded."

The one nearer the camera in the photo above (shown here at the left) is dedicated to Mary. The one at the back holds the bones of Charlemagne, and surprisingly, all evidence points to their being genuine. Only about 100 bones are present, clearly not an entire human body, but they are human, they're all from the same very tall individual, and they are of the right absolute age and the right age at death. And they've been right here the whole time—they haven't been schlepped all over Europe, brought back from a crusade, transferred from one church to another, etc. A few more of his bones (also from the same individual) are accounted for downstairs in the treasury (in other reliquaries), but the guide hypothesizes that some of his successors might have been tempted to make off with a finger or toe here or there as a sort of talisman.

The one nearer the camera in the photo above (shown here at the left) is dedicated to Mary. The one at the back holds the bones of Charlemagne, and surprisingly, all evidence points to their being genuine. Only about 100 bones are present, clearly not an entire human body, but they are human, they're all from the same very tall individual, and they are of the right absolute age and the right age at death. And they've been right here the whole time—they haven't been schlepped all over Europe, brought back from a crusade, transferred from one church to another, etc. A few more of his bones (also from the same individual) are accounted for downstairs in the treasury (in other reliquaries), but the guide hypothesizes that some of his successors might have been tempted to make off with a finger or toe here or there as a sort of talisman.

The other (shown at the right) contains four textiles, purporting to be the first and last garments of Christ—his swaddling cloths and the loincloth he wore on the cross. They were probably actually made during the 2nd and 8th centuries.

On Mary's reliquary, Mary and the child are on the front; one the end is the pope who crowned Charlemagne, surrounded by disciples; on the second broad side, Charlemagne and some disciples; and on the second end, Jesus Christ. Both reliquaries were made around 1200. Charlemagne's reliquary is opened every seven years and the relics presented to the people. The next occasion will be June of this year, and they expect 120,000 people to come. The next time will be only five years later, because the one coming up in June was delayed by two years by the pandemic, and they want to get back to the old seven-year cycle. Charlemagne's reliquary has 8 eight figures on each side (8 again); they were kings who were successors of his, and they guard the tomb of their predecessor. On one end are Mary and a couple of angels, and on the other two standing church men (a bishop and a pope) flanking Charlemagne. Charlemagne is seated but is still taller than the two standing guys. They also have to bow a little because they're standing under arches that aren't quite tall enough.

Charlemagne was sainted in the 12th century, but only by Antipope Paascal III, so the Catholic church doesn't now recognize him as a saint (I found this out later; in Aachen, they just call him a saint). He is recognized as beatified, though.

The 16th-century suspended starburst shows Mary as the apocolyptic woman.

The walls of the choir hall bear several layers of painting, part 15th century, part 17th.

From the choir hall, we passed back through the lower level of the octagonal church, where a huge iron chandelier is hung from the center of the dome by a chain. It was donated by Frederick I (Barbarossa), one of Charlemagne's successors as holy roman emperor, on the occasion of Charlemagne's sainthood. The craftsment who made it actually made the upper links of the chain thicker than those lower down, to account for parallax, so they all look the same thickness when viewed from below.

It takes real candles, and it can't be lowered, but for special occasions, they take out the chairs, set up scaffolding so s to load it with real candles. It used to be covered with precious stones and have little silver things inside (8) metal towers around the rim, but they've all been pilfered over the years. They tried to blame the French (the one who took the columns), but that's probably not right.

Next, we went outside, around the corner, and back inside, then downstairs to the treasury (which is rated as one of the top two treasuries in Europe), first locking all our coats, hats, etc. in lockers.

Next, we went outside, around the corner, and back inside, then downstairs to the treasury (which is rated as one of the top two treasuries in Europe), first locking all our coats, hats, etc. in lockers.

At the left here is a reliquary in the shape of a forearm which holds, and displays through a transparent window, a piece of Charlemagne's radius, or perhaps ulna. At the right is one in the shape of a head that contains a piece of his skull, apparently positioned inside as it would have been in the living man's head. The image is pretty blurry, but on the head are both an eagle and a fleur de lis, because he was the founding father of both Germany and France.

The guide told us that these two bone fragments have been verified to come from the same individual as those upstairs. One of our group asked whether they did so by testing the DNA, but the guide said no, it wasn't DNA, but he didn't know what test they did use.

This large ceremonial cross was quite plain on the front (left) but covered with precious stones on the back. It dates only from the year 2000 and it's still in use—they move it upstairs to the church for special occasions. Apparently the stones represent the buildings of the heavenly city and the spaces between them the streets of gold.

This large ceremonial cross was quite plain on the front (left) but covered with precious stones on the back. It dates only from the year 2000 and it's still in use—they move it upstairs to the church for special occasions. Apparently the stones represent the buildings of the heavenly city and the spaces between them the streets of gold.

Our city guide had told us that the chapter had turned down an offer of $125 million for "a large gilded cross." I guess this must be it, though our cathedral guide didn't mention it.

The treasury also included coronation objects and things Charlemagne collected on his travels. Among the latter was this marble sarcophagus, dating from about 200 AD and decorated with scenes of the abduction of Persephone. It served as Charlemagne's first tomb, until his remains were transferred to the present reliquary on the occasion of his sainthood.

The treasury also included coronation objects and things Charlemagne collected on his travels. Among the latter was this marble sarcophagus, dating from about 200 AD and decorated with scenes of the abduction of Persephone. It served as Charlemagne's first tomb, until his remains were transferred to the present reliquary on the occasion of his sainthood.

Among things added after his time were this altarpiece, made for a church in Cologne but purhased and brought here. In it, good people are portrayed on Christ's right hand (our left) and bad people to his left (our right). The monk who commissioned the altarpiece is portrayed on the side of the angels (kneeling in the left foreground), but his bishop, with whom he was always in conflict, is on the white horse at the right. The horse even presents to the viewer the monk's opinion of the bishop.

The people are portrayed in a European landscape and in the dress of the period when the artist lived. The soldier on the "bad" side is dressed as a Turk, the enemy of the time. The artist was also interested in medicine, as many medical conditions are portrayed, including trisomy 21, at the lower left. The figure of Venus, a statuette at the upper left, is depicted as suffering from siphylis. We asked who did the painting, but the artist is known only as "the master of the Aachen altar."

Among the myriad other objects on display were the oldest wooden door in Europe (not in very good shape); a sumptuously decorated golden bucket from about 1000 AD (probably intended for a single use, to hold holy water during a coronation; it echoes the architecture o the cathedral, with upper and lower levels, and columns); and all the padlocks cut off when the shrine was opened over the last 620 years (all different and designed for the purpose), including the one that will be used to close it in June. The key is divided in half, and one half goes to the church and the other to the city of Aachen.

After retrieving all our paraphernalia from the lockers, we strolled back toward our bus, passing en route this lovely pastry shop. At the left are savory breads and at the right yummy-looking pastries (kirsch-flavored, with marzipan) and pies.

After retrieving all our paraphernalia from the lockers, we strolled back toward our bus, passing en route this lovely pastry shop. At the left are savory breads and at the right yummy-looking pastries (kirsch-flavored, with marzipan) and pies.

Another thing that because clear when I learned that Aachen was Aix-la-Chapelle is that, like "Aix," "Aachen" is derived from the Latin "aqua." It has thermal mineral springs. I wonder whether that's why Charlemagne settled here?! Today, only a single establishment is still active, but the guide led us by it, where under this semicircular colonaded porch, you can sample the (sulfur-flavored) water. I didn't.

Another thing that because clear when I learned that Aachen was Aix-la-Chapelle is that, like "Aix," "Aachen" is derived from the Latin "aqua." It has thermal mineral springs. I wonder whether that's why Charlemagne settled here?! Today, only a single establishment is still active, but the guide led us by it, where under this semicircular colonaded porch, you can sample the (sulfur-flavored) water. I didn't.

Back in the bus, we once again learned a lot from the guide:

- In Germany (or maybe he meant in the Netherlands?), for tax purposes, you have to register your religion, because you are charged a church tax, and the government has to know which church to send yours to. Somehow I doubt they would let you skip paying the tax if you don't subscribe to a religion.

- We drove in and out of town along the site of the outer ring wall, medieval architecture to teh left, newer stuff to the right.

- Aachen has 250,000 inhabitants; it's about twice the size of Maastricht. Its technical university has 60,000 students.

- In Aachen, brass nails in the pavement in the shape of Charlemagne's signature mark a tourist route through the city. We saw them but had no chance to follow the walking route.

- The oldest parish church of Aachen was mostly destroyed in the war, and its been being rebuilt ever since.

- Early on, Aachen started going protestant but then changed its mind.

- In the 1970's, coal stopped being profitable, so Heerlen, the town we were passing through has struggled because all its coal mines closed, leading to unemployment, drugs, and alcohol abuse.In the last 15 years, tourism has begun to take up the slack. The region is popular with tourists for its hiking, nice city center, and hundreds of kilometers of caves to be explored (left over from hundreds of years of mining of soft sandstone, starting in Roman times). You can rent a cave to have a party in or take a guide tour of the caves.

- A little ceramics and paper industry is left in Maastricht, but most of the old industrial stuff has left. Now it's a university town, though it's only half the size of Aachen. It is, according to our guide, one of the gems, where a lot of things are happening, it has a lot of beautiful old culture.

- Limburg province has lots of agriculture, and it includes the highest elevations in the region. The highest point is 22 m elevation.

- The restaurant Julemont, in Chateau Wittem, got two Michelin stars in its first year. It overlooks the Guel River (pronounced "hewel").

- This area has only about 20,000 inhabitants, but it has two two-star restaurants.

- Germany's reunification was very, very expensive, so road maintenance was one of the things that suffered. You can tell when you cross the border into Germany; the roads go from smooth to bumpy.

- Hedges have been taken out to give bigger agricultural fields, but that has hurt biodiversity of small animals, so they're trying to put the hedges back.

- An old monastery we passed is still occupied by a few monks.

- We'll be crossing into Belgium for a couple of minutes to get back on the the ship in Gellik, but then we'll cruise back into the Netherlands once we're aboard.

- Real estate on the Belgian side has recently been a lot cheaper, so Dutch have been buying on the belgian side, still within in easy reach of Maastricht.

- After losing in some war (in 1792 maybe?) Belgium came under Dutch rule, but it became independent in 1830.

We had to take Viking's word that we were in Gellik, as we never saw a town. The bus just turned down a side road that slanted down along the face of the dike to the water's edge, not a building in sight, where, sure enough, the Freya was waiting for us. We were just in time for dinner.

I started with a regional specialty, North Sea shrimp with lemon mayo on tomato carpaccio.

I started with a regional specialty, North Sea shrimp with lemon mayo on tomato carpaccio.

I think David had the cream of Belgium endive soup with garlic chips, but I didn't get a photo.

For the main course we both passed up the vegetarian moussaka for roast châteaubriand with béarnaise sauce and potato gratin. Excellent.

For dessert, I went regional again with "oliebollen," little spherical Dutch donuts dusted with finely ground coconut.

For dessert, I went regional again with "oliebollen," little spherical Dutch donuts dusted with finely ground coconut.

David went international with moelleux au chocolat—chocolate lava cake. Both very good.

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

In the morning, we had the difficult choice between a pie-baking workshop, where we would learn how to make the famous "vlaai" at a historic bakery, and a walking tour of the town's streets and squares. We chose the latter. We were able to walk off the ship, across the road, and straight into the town.

In the morning, we had the difficult choice between a pie-baking workshop, where we would learn how to make the famous "vlaai" at a historic bakery, and a walking tour of the town's streets and squares. We chose the latter. We were able to walk off the ship, across the road, and straight into the town.

The bridge shown at the left here, a little farther along the river, was built to replace the Roman one and is the oldest bridge in the Netherlands. The locals blew up the right-hand end of it at the beginning of WWII, to slow the German advance; the Germans rebuilt it, but then it got blown up again when they left. It's now reserved for pedestrians, and they never rebuilt the blown-up part in stone. It's hard to see in this photo, but the last couple of arches at the right-hand end have been replaced by a single metal span.

The bridge shown at the left here, a little farther along the river, was built to replace the Roman one and is the oldest bridge in the Netherlands. The locals blew up the right-hand end of it at the beginning of WWII, to slow the German advance; the Germans rebuilt it, but then it got blown up again when they left. It's now reserved for pedestrians, and they never rebuilt the blown-up part in stone. It's hard to see in this photo, but the last couple of arches at the right-hand end have been replaced by a single metal span.

Here we have the bottom (left) and top (right) halves of the facade of the basilica of St. Servatius. I had no room to back up far enough to get all of it into one shot.

Here we have the bottom (left) and top (right) halves of the facade of the basilica of St. Servatius. I had no room to back up far enough to get all of it into one shot.

As usual, the bronze model outside, labeled in Braille, gives a better idea of the appearance of the building than I could manage in photos of the real thing.

As usual, the bronze model outside, labeled in Braille, gives a better idea of the appearance of the building than I could manage in photos of the real thing.

Maastricht is full of whimsical statuary, but the piece at the left here is the most celebrated. It's the Mestreechter Geis, by Mari Andriessen, intended to represent the spirit, character, and disposition of Maastricht and its people—enjoying the good things in life, a little nonchalant, always eager to put things in proper perspective. I had to stop and ask myself why that characterization surprised me—why I had always thought of Maastricht as stern and reserved. I realized that my impression had been formed by just two factors: (a) the Maastricht Treaty, establishing the European Union and thus a whole set of rules governing life in Europe, was signed there and (b) the name includes a syllable pronounced "strict"!

Maastricht is full of whimsical statuary, but the piece at the left here is the most celebrated. It's the Mestreechter Geis, by Mari Andriessen, intended to represent the spirit, character, and disposition of Maastricht and its people—enjoying the good things in life, a little nonchalant, always eager to put things in proper perspective. I had to stop and ask myself why that characterization surprised me—why I had always thought of Maastricht as stern and reserved. I realized that my impression had been formed by just two factors: (a) the Maastricht Treaty, establishing the European Union and thus a whole set of rules governing life in Europe, was signed there and (b) the name includes a syllable pronounced "strict"!

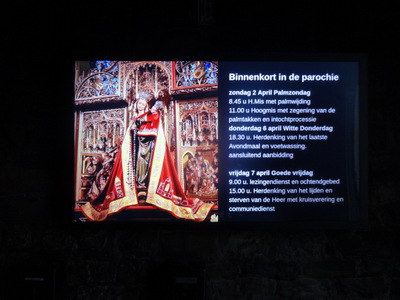

I had forgotten that it was Palm Sunday, so I was initially puzzled by the group of old men who walked by, each holding a little bouquet of boxwood sprigs, but more and more people passed, all carrying boxwood, even the little children. Apparently boxwood is the approved local stand-in for palm fronds to take with you to church.

I had forgotten that it was Palm Sunday, so I was initially puzzled by the group of old men who walked by, each holding a little bouquet of boxwood sprigs, but more and more people passed, all carrying boxwood, even the little children. Apparently boxwood is the approved local stand-in for palm fronds to take with you to church.

Here, at the left, is a nearer view. At the right is a photo of posted in inside of that same statue on a more special occasion, in more oppulent dress.

Here, at the left, is a nearer view. At the right is a photo of posted in inside of that same statue on a more special occasion, in more oppulent dress.

As we strolled back toward the Bishop's Mill, next on our itinerary, we passed this especially gorgeous Japanese andromeda (Pieris japonica). The flowers are white and the new foliage is red.

As we strolled back toward the Bishop's Mill, next on our itinerary, we passed this especially gorgeous Japanese andromeda (Pieris japonica). The flowers are white and the new foliage is red.

We approached the mill from the rear, so as to see the waterwheel, and that allowed us to see, through this back window, an array of sausage rolls in the making. A baker had just extruded a stripe of raw sausage mixture onto each of the oval pieces of raw pastry dough and would presumably soon fold them up into cylinders for baking.

We approached the mill from the rear, so as to see the waterwheel, and that allowed us to see, through this back window, an array of sausage rolls in the making. A baker had just extruded a stripe of raw sausage mixture onto each of the oval pieces of raw pastry dough and would presumably soon fold them up into cylinders for baking.

At the left here is only a small part of the shop's display window, featuring an assortment of the vlaai that the whole region is known for.

At the left here is only a small part of the shop's display window, featuring an assortment of the vlaai that the whole region is known for.

Another of the city's whimsical statues is this one of Alphonse "Fons" Olterdissen, a Dutch writer, poet, and composer who wrote a lot in the Maastrichtian dialect. Maastricht residents have adopted the final stanza of his 1910 opera Trijn de Begijn as the town's song (the city council adopted it formally in 2002). It's always sung at the end of André Riu's concerts here and apparently everywhere else, too—scout meetings, class outings, any gathering of the town's people. The guide sang it for us on the spot. It started out "Vivat! Vivat!" before lapsing into dialect I couldn't follow. It apparently describes the history of the city, good times, bad times, many wars, and the good way of living of the Maastricht people.

Another of the city's whimsical statues is this one of Alphonse "Fons" Olterdissen, a Dutch writer, poet, and composer who wrote a lot in the Maastrichtian dialect. Maastricht residents have adopted the final stanza of his 1910 opera Trijn de Begijn as the town's song (the city council adopted it formally in 2002). It's always sung at the end of André Riu's concerts here and apparently everywhere else, too—scout meetings, class outings, any gathering of the town's people. The guide sang it for us on the spot. It started out "Vivat! Vivat!" before lapsing into dialect I couldn't follow. It apparently describes the history of the city, good times, bad times, many wars, and the good way of living of the Maastricht people.

Here's another view of the Jeker. You can just see it foaming through the water gate in an old section of town wall, farthest from the camera, an indication that it really is running high, despite its calm appearance elsewhere. The gate could be closed in case of attack. The guide told us the river had been "replaced" (rerouted, maybe, to suit the millers' convenience?).

Here's another view of the Jeker. You can just see it foaming through the water gate in an old section of town wall, farthest from the camera, an indication that it really is running high, despite its calm appearance elsewhere. The gate could be closed in case of attack. The guide told us the river had been "replaced" (rerouted, maybe, to suit the millers' convenience?).

Regular readers will know my habit of photographing (and often of riding on) little touristy sight-seeing trains. Coming along the street toward us (left) and passing by (right), looking like nothing so much as a bus-stop shelter on wheels, is the local "little white train." We didn't get to ride one this trip, as we were continously in the hands of knowledgeable local guides, either on foot or in bigger buses.

Regular readers will know my habit of photographing (and often of riding on) little touristy sight-seeing trains. Coming along the street toward us (left) and passing by (right), looking like nothing so much as a bus-stop shelter on wheels, is the local "little white train." We didn't get to ride one this trip, as we were continously in the hands of knowledgeable local guides, either on foot or in bigger buses.

Here, at last, is Vrijthof Square, the vast central square we had heard about. We crossed it about in the middle, so there's as much of it behind me as appears in the photo.

Here, at last, is Vrijthof Square, the vast central square we had heard about. We crossed it about in the middle, so there's as much of it behind me as appears in the photo.

The Sunday morning church bells were ringing as we made our way back to the ship for Sunday lunch.

The Sunday morning church bells were ringing as we made our way back to the ship for Sunday lunch.

Lunch was underwhelming. The fine-print appetizers were actually pretty good—a mixed seafood salad and actual vitello tonnato—cold roast veal with tuna sauce, an Italian classic—made with the left-over roast veal from the previous night.

Lunch was underwhelming. The fine-print appetizers were actually pretty good—a mixed seafood salad and actual vitello tonnato—cold roast veal with tuna sauce, an Italian classic—made with the left-over roast veal from the previous night.

Then it was back into the buses for our tour of Charlemagne's cathedral and treasury in Aachen, Germany. As we pulled away, the ship cast off behind us, headed for our afternoon rendez-vous point in Gellik, Belgium.

Then it was back into the buses for our tour of Charlemagne's cathedral and treasury in Aachen, Germany. As we pulled away, the ship cast off behind us, headed for our afternoon rendez-vous point in Gellik, Belgium.

My first impression of Charlemagne's cathedral was dominated by the two absolutely magnificent Japanese magnolias that flank its door. They were in the fullest bloom possible, and I've never seen finer specimens. I'm sure Charlemagne (747–814 AD) never saw them, but they are an excellent addition.

My first impression of Charlemagne's cathedral was dominated by the two absolutely magnificent Japanese magnolias that flank its door. They were in the fullest bloom possible, and I've never seen finer specimens. I'm sure Charlemagne (747–814 AD) never saw them, but they are an excellent addition.

Inside the cathedral, the local city guide (to whom our program director had turned us over) turned us over to the cathedral's offical guide. We started by climbing to second-floor level.

Inside the cathedral, the local city guide (to whom our program director had turned us over) turned us over to the cathedral's offical guide. We started by climbing to second-floor level.

At the left here is a view up into the dome of the central part of the church, the part dating from Charlemagne's time. At the right is the view down into the lower level of the central part. We were standing on the second-floor gallery that runs around the sides of it. We were warned not to lean on the bronze railing we had to look over to see the lower section, because it does date from Charlemagne's time and might be a little fragile. Back in the day, it and all the other bronze fittings would have been polished to gleam like gold. The gallery where we stood was the local parish church, with its own altar and baptismal font, whereas the lower level was the "collegiate" church used by the priests of the chapter. It also serves as the cathedral for the diocese of Aachen. The guide described it as "also the episcopal [meaning "of the bishop"] church of the diocese," causing momentary confusion in those who took the word to refer to the protestant denomination. Each of the priests in the chapter, and there were lots, had to say mass several times a day, so the building housed more than 30 altars, all of which were kept busy. Today, at least two services a day take place here; they are always in the morning so that tours can be conducted in the afternoon.

At the left here is a view up into the dome of the central part of the church, the part dating from Charlemagne's time. At the right is the view down into the lower level of the central part. We were standing on the second-floor gallery that runs around the sides of it. We were warned not to lean on the bronze railing we had to look over to see the lower section, because it does date from Charlemagne's time and might be a little fragile. Back in the day, it and all the other bronze fittings would have been polished to gleam like gold. The gallery where we stood was the local parish church, with its own altar and baptismal font, whereas the lower level was the "collegiate" church used by the priests of the chapter. It also serves as the cathedral for the diocese of Aachen. The guide described it as "also the episcopal [meaning "of the bishop"] church of the diocese," causing momentary confusion in those who took the word to refer to the protestant denomination. Each of the priests in the chapter, and there were lots, had to say mass several times a day, so the building housed more than 30 altars, all of which were kept busy. Today, at least two services a day take place here; they are always in the morning so that tours can be conducted in the afternoon.

At the left here is a better view of the lower part of the dome, showing the columns in the arches and Schaper's mosaics behind them.

At the left here is a better view of the lower part of the dome, showing the columns in the arches and Schaper's mosaics behind them.

At the right, still at second floor level where we stood, is Charlemagne's throne, facing out over the railing overlooking the church below. As you can see, it's pretty rudimentary and downright tatty compared with all the gilding elsewhere. It's made of flat slabs of whitish stone bolted together with metal angle-irons. The slabs were clearly scavenged, as one of them on the far side is actually engraved with the grid for an ancient board game now called "nine men's morris." Clearly these stone slabs had some historical or mystical importance to Charlemagne, and since he revered them, generations afterward have continued to do so.

At the right, still at second floor level where we stood, is Charlemagne's throne, facing out over the railing overlooking the church below. As you can see, it's pretty rudimentary and downright tatty compared with all the gilding elsewhere. It's made of flat slabs of whitish stone bolted together with metal angle-irons. The slabs were clearly scavenged, as one of them on the far side is actually engraved with the grid for an ancient board game now called "nine men's morris." Clearly these stone slabs had some historical or mystical importance to Charlemagne, and since he revered them, generations afterward have continued to do so.

The one nearer the camera in the photo above (shown here at the left) is dedicated to Mary. The one at the back holds the bones of Charlemagne, and surprisingly, all evidence points to their being genuine. Only about 100 bones are present, clearly not an entire human body, but they are human, they're all from the same very tall individual, and they are of the right absolute age and the right age at death. And they've been right here the whole time—they haven't been schlepped all over Europe, brought back from a crusade, transferred from one church to another, etc. A few more of his bones (also from the same individual) are accounted for downstairs in the treasury (in other reliquaries), but the guide hypothesizes that some of his successors might have been tempted to make off with a finger or toe here or there as a sort of talisman.

The one nearer the camera in the photo above (shown here at the left) is dedicated to Mary. The one at the back holds the bones of Charlemagne, and surprisingly, all evidence points to their being genuine. Only about 100 bones are present, clearly not an entire human body, but they are human, they're all from the same very tall individual, and they are of the right absolute age and the right age at death. And they've been right here the whole time—they haven't been schlepped all over Europe, brought back from a crusade, transferred from one church to another, etc. A few more of his bones (also from the same individual) are accounted for downstairs in the treasury (in other reliquaries), but the guide hypothesizes that some of his successors might have been tempted to make off with a finger or toe here or there as a sort of talisman.

Next, we went outside, around the corner, and back inside, then downstairs to the treasury (which is rated as one of the top two treasuries in Europe), first locking all our coats, hats, etc. in lockers.

Next, we went outside, around the corner, and back inside, then downstairs to the treasury (which is rated as one of the top two treasuries in Europe), first locking all our coats, hats, etc. in lockers.

This large ceremonial cross was quite plain on the front (left) but covered with precious stones on the back. It dates only from the year 2000 and it's still in use—they move it upstairs to the church for special occasions. Apparently the stones represent the buildings of the heavenly city and the spaces between them the streets of gold.

This large ceremonial cross was quite plain on the front (left) but covered with precious stones on the back. It dates only from the year 2000 and it's still in use—they move it upstairs to the church for special occasions. Apparently the stones represent the buildings of the heavenly city and the spaces between them the streets of gold.

The treasury also included coronation objects and things Charlemagne collected on his travels. Among the latter was this marble sarcophagus, dating from about 200 AD and decorated with scenes of the abduction of Persephone. It served as Charlemagne's first tomb, until his remains were transferred to the present reliquary on the occasion of his sainthood.

The treasury also included coronation objects and things Charlemagne collected on his travels. Among the latter was this marble sarcophagus, dating from about 200 AD and decorated with scenes of the abduction of Persephone. It served as Charlemagne's first tomb, until his remains were transferred to the present reliquary on the occasion of his sainthood.

After retrieving all our paraphernalia from the lockers, we strolled back toward our bus, passing en route this lovely pastry shop. At the left are savory breads and at the right yummy-looking pastries (kirsch-flavored, with marzipan) and pies.

After retrieving all our paraphernalia from the lockers, we strolled back toward our bus, passing en route this lovely pastry shop. At the left are savory breads and at the right yummy-looking pastries (kirsch-flavored, with marzipan) and pies.

Another thing that because clear when I learned that Aachen was Aix-la-Chapelle is that, like "Aix," "Aachen" is derived from the Latin "aqua." It has thermal mineral springs. I wonder whether that's why Charlemagne settled here?! Today, only a single establishment is still active, but the guide led us by it, where under this semicircular colonaded porch, you can sample the (sulfur-flavored) water. I didn't.

Another thing that because clear when I learned that Aachen was Aix-la-Chapelle is that, like "Aix," "Aachen" is derived from the Latin "aqua." It has thermal mineral springs. I wonder whether that's why Charlemagne settled here?! Today, only a single establishment is still active, but the guide led us by it, where under this semicircular colonaded porch, you can sample the (sulfur-flavored) water. I didn't.

I started with a regional specialty, North Sea shrimp with lemon mayo on tomato carpaccio.

I started with a regional specialty, North Sea shrimp with lemon mayo on tomato carpaccio.

For dessert, I went regional again with "oliebollen," little spherical Dutch donuts dusted with finely ground coconut.

For dessert, I went regional again with "oliebollen," little spherical Dutch donuts dusted with finely ground coconut.