Saturday, 13 June 2009, Dijon to Gilly

Written 15 June 2009

Last breakfast at the Ibis Arquebuse Dijon: The buffet here is of the moderately extensive sort. Three kinds bread (including baguettes), croissants, pains au chocolat, flat unfilled minicrepes, potato-egg tortilla (for the Spaniards), minimuffins, two pound cakes, pain d'épices, yogurt, fromage blanc, many jams (in jars rather than single-serve packs and including my favorite, cerise griotte, i.e. morello cherry), honey, nutella, fresh whole fruit, a drink machine (dispensing many variations on coffee, chocolate, hot milk, and hot water), cheese and ham (for the Germans), applesauce. And, in keeping with today's health trends, many little signs alerting the clientel that such and such a food contains "fast sugars" (nutella, orange juice, jam), "slow sugars" (crêpes, bread), or "proteins" (yogurt).

Next, off to Gilly-les-Cîteaux. I have no idea what "Gilly" means, but "Cîteaux" is derived from "cistels" the "reeds" after which the Cistercians are named. Photos we've been shown of "cistels" showed something that's clearly either a grass or a sedge, but wherever we've been proudly shown a commemorative patch of real ones, they've been cattails. Gotta look that one up.

Next, off to Gilly-les-Cîteaux. I have no idea what "Gilly" means, but "Cîteaux" is derived from "cistels" the "reeds" after which the Cistercians are named. Photos we've been shown of "cistels" showed something that's clearly either a grass or a sedge, but wherever we've been proudly shown a commemorative patch of real ones, they've been cattails. Gotta look that one up.

The drive was short, less than an hour. On the way out of Dijon, I spotted a billboard advertising Mercedes that included the notation, "starting at 130 g carbon/km." Europe really is taking this carbon-footprint thing seriously. In Gilly, we found our hotel, l'Orée des Vignes (The Verge of the Vines) very easily—the town is very, very small—and very charming. You enter the hotel through modern glass doors from the little gravel parking lot and cross this immaculate courtyard to the reception lobby. Just out of the photo to the left are two short rows of vines, bearing (like the commerically harvested ones outside) extremely tiny new green grapes. I don't know how old the building is, but the appointments are all very new and modern and priced at about a third of what you would pay for the cheapest room at the Château de Gilly, a short walk away, where we had dinner reservations (and which was the only lodging Gault Millau listed for the town).

The day was young, so we set out in search of adventure and lunch and found, first of all, this handsome little planting in the "town square" just outside the gates of the château. The Fromagerie Delin is located in Gilly and is highly advertised on the web and in brochures in hotel lobbies for miles around. We could have walked there but took the car because we planned to go further afield afterwards. As I suspected, though, all you can visit is the shop—the actual cheese-making operation is not set up for tours. Delin makes soft, fresh cheeses, fromage blanc, Brillat-Savarin, Fleur de Nuits-St.-George, and a variety of processed cheeses coated with raisins, herbs, or whatnot, as well as crême fraiche, butter, and other small cheeses I've never heard of. They also sell some prominent cheeses made by others, like this Cîteaux, made at the nearby Abbey.

The day was young, so we set out in search of adventure and lunch and found, first of all, this handsome little planting in the "town square" just outside the gates of the château. The Fromagerie Delin is located in Gilly and is highly advertised on the web and in brochures in hotel lobbies for miles around. We could have walked there but took the car because we planned to go further afield afterwards. As I suspected, though, all you can visit is the shop—the actual cheese-making operation is not set up for tours. Delin makes soft, fresh cheeses, fromage blanc, Brillat-Savarin, Fleur de Nuits-St.-George, and a variety of processed cheeses coated with raisins, herbs, or whatnot, as well as crême fraiche, butter, and other small cheeses I've never heard of. They also sell some prominent cheeses made by others, like this Cîteaux, made at the nearby Abbey.

Note to CJ: We've had many chances to eat Cîteaux on this trip. It's pretty well unknown in the U.S., but highly esteemed here (30 monks probably can't turn out enough of it to supply both the local and the export market), but now hear this, CJ, if you ever get a chance to visit this area, you would really, really like this cheese! David didn't care for it at first taste, but it has grown on him, and he orders it at nearly every opportunity now.

That didn't take long, so we set off a little farther afield, like 3 km across the main highway to Clos de Vougeot to visit its castle. I have always been confused by the names of wines from Burgundy, but being here on the ground and seeing all the diagrams, reading the history, and listening to the tour guides, I'm beginning to make sense of it. To oversimplify a little, a line of cities runs along the D974 from Dijon in the north to Beaune, to Chalons-sur-Sâone, to Macon at the bottom (with many little towns in between). In parallel, a long range of hills runs north-south just west of the towns. "Côte" (in the context of wines) means "hillside," and the vines that produce Burgundy's grapes (Chardonnay for the whites and Pinot Noir for the reds and rosés) are grown on the eastern sides of those hills. That long line of hillsides is divided into regions named for the towns they face—the ones we're exploring this week are the "Côtes de Nuits" (the hillsides facing the town of Nuits-St.-Georges, about a kilometer from Gilly, where we are now, halfway between Dijon and Beaune) and the "Côtes de Beaune" (the hillsides facing Beaune, south of the Côtes de Nuits). South of that are, successively, the "Cauchois" and "Challonais" (facing Chalons) and the "Maconnais" (facing Macon). South of that you're into Beaujolais country, where they grow Gamay grapes. Some grapes are grown on the flat near the highway, at the feet of the hills, but they're not considered the best. As you climb the hills, you come to areas labeled "Hautes Côtes" (high hillsides). Their microclimates are a shade cooler, and their weather is chancier, so they suffer more frequent failures of quality. Because their wines are a little more acidic, they are often used to make "Crémants de Bourgogne," sparkling burgundies. The whole thing, collectively, is called the "Côte d'Or," the golden hillsides.

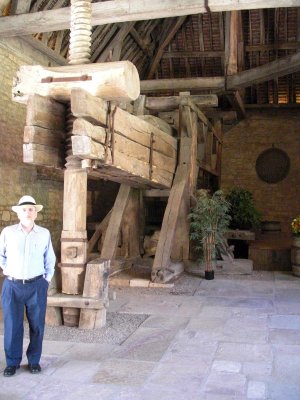

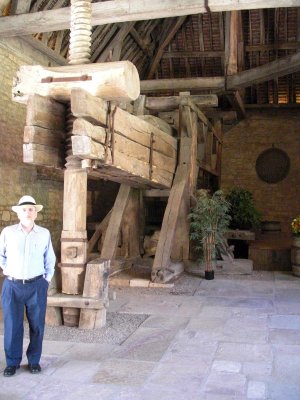

Within the Côtes, the hillsides are divided up into dozens of smaller designations, mostly named for the towns they surround, like Aloxe-Corton and Marsannay and Chambolle-Mussigny. A particularly prestigious designation is "Clos de Vougeot"—it seems the monks at the Abbey of Cîteaux owned land near Nuits-St.-Georges that produced particularly good wine, and they marked out a segment of the region (about 40 ha, I think) that they wanted to acquire all of, and with the persistence of an institution in it for the long term, set about acquiring. In fact, they built a wall around it (the "clos" or enclosure) before they had actually laid hands on all the land inside. On the site, in stages from the 12th to the 16th century, they built a magnificent winery (the Château du Clos de Vougeot) with four huge presses, aging rooms, etc. The view on the left shows the press building from the main courtyard, and the one on the right shows David standing next to the lever shaft of one of the four massive presses (the one nicknamed "the Stubborn"). The press building is square, arranged around a smaller, inner courtyard, and one press occupies each corner. The abbey fell on hard times later, though, and lost ownership of the land. Nowadays, that 40 ha is divided among about 60 owners, all of whom grow grapes and produce wine and all of whom are entitled to the "appellation controlée" (legally protected "brand name") "Clos de Vougeot." The Château is now the worldwide headquarters of the Confrerie des Chevaliers du Tastevin (the Brotherhood of the Cavaliers of Winetasting), which throws elaborate banquets at least annually, presided over by famous people (like royalty, astronauts, etc.), presumably members of the brotherhood. It's open for self-guided tours.

Within the Côtes, the hillsides are divided up into dozens of smaller designations, mostly named for the towns they surround, like Aloxe-Corton and Marsannay and Chambolle-Mussigny. A particularly prestigious designation is "Clos de Vougeot"—it seems the monks at the Abbey of Cîteaux owned land near Nuits-St.-Georges that produced particularly good wine, and they marked out a segment of the region (about 40 ha, I think) that they wanted to acquire all of, and with the persistence of an institution in it for the long term, set about acquiring. In fact, they built a wall around it (the "clos" or enclosure) before they had actually laid hands on all the land inside. On the site, in stages from the 12th to the 16th century, they built a magnificent winery (the Château du Clos de Vougeot) with four huge presses, aging rooms, etc. The view on the left shows the press building from the main courtyard, and the one on the right shows David standing next to the lever shaft of one of the four massive presses (the one nicknamed "the Stubborn"). The press building is square, arranged around a smaller, inner courtyard, and one press occupies each corner. The abbey fell on hard times later, though, and lost ownership of the land. Nowadays, that 40 ha is divided among about 60 owners, all of whom grow grapes and produce wine and all of whom are entitled to the "appellation controlée" (legally protected "brand name") "Clos de Vougeot." The Château is now the worldwide headquarters of the Confrerie des Chevaliers du Tastevin (the Brotherhood of the Cavaliers of Winetasting), which throws elaborate banquets at least annually, presided over by famous people (like royalty, astronauts, etc.), presumably members of the brotherhood. It's open for self-guided tours.

We also admired this well, in another enclosure off the main courtyard. A couple of men pulled on the knotted rope that passed over the large wheel in the back. It turned the smaller wheel over the well (gaining considerable mechanical advantage from the difference in their diameters), raising a bucket out of the well (one much larger than the one full of germaniums). A thick plank fixed to a pivot at one end (on which the geraniums are resting) could then be slid under the bucket to hold it while the bucket was tilted to dump the water into a barrel for transport to the vines. The right-hand photo shows one of the vines just outside the gates, complete with very tiny green grapes.

We also admired this well, in another enclosure off the main courtyard. A couple of men pulled on the knotted rope that passed over the large wheel in the back. It turned the smaller wheel over the well (gaining considerable mechanical advantage from the difference in their diameters), raising a bucket out of the well (one much larger than the one full of germaniums). A thick plank fixed to a pivot at one end (on which the geraniums are resting) could then be slid under the bucket to hold it while the bucket was tilted to dump the water into a barrel for transport to the vines. The right-hand photo shows one of the vines just outside the gates, complete with very tiny green grapes.

Written 16 June 2009

Strangely, despite analyzing the soils and climates up, down, and sideways, no one has ever really figured out why one field of vines consistently produces better wine than another field a quarter of a mile away. The difference is extremely durable—the Clos de Vougeot has been producing wine better than that from fields surrounding it for at least 900 years, despite erosion and changes in philosophy of pruning, fertilization, mechanization, ownership, etc. Even the vines have been replaced repeatedly. Amazing.

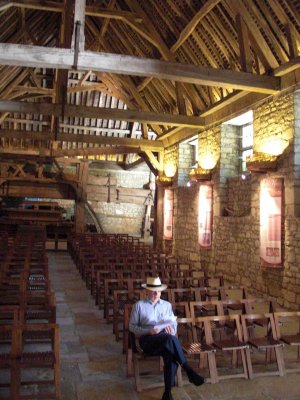

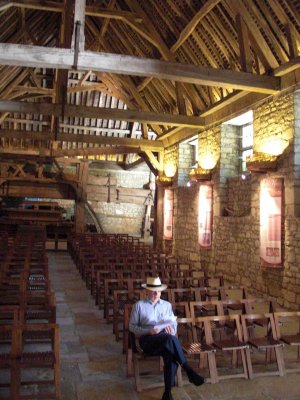

At the château, we were able to peer into the "wine library," a room lined with thousands of carefully labeled bottles, presumably of wines produced over the years (centuries?) in the clos. The fermenting and aging rooms have been redone as meeting space for the brotherhood. When we were there, one section of the pressing room was set up as an auditorium (I took this photo of David from the speaker's stand, with my back to "the Stubborn"; you can see the lever shaft of another of the presses against the back wall). Another room was set up with banquet tables, and to our delight, the kitchens were busy preparing for some sort of gala dinner! The doors and windows were wide open, so we were able to stand outside and watch. They were making a huge number of these little pastry packages. Each one was stuffed with what looked like two pieces of raw meat (duck?) sandwiching a stuffing of some kind. I'm guessing the casing was puff pastry, which would puff up and get crisp at the edges when baked.

At the château, we were able to peer into the "wine library," a room lined with thousands of carefully labeled bottles, presumably of wines produced over the years (centuries?) in the clos. The fermenting and aging rooms have been redone as meeting space for the brotherhood. When we were there, one section of the pressing room was set up as an auditorium (I took this photo of David from the speaker's stand, with my back to "the Stubborn"; you can see the lever shaft of another of the presses against the back wall). Another room was set up with banquet tables, and to our delight, the kitchens were busy preparing for some sort of gala dinner! The doors and windows were wide open, so we were able to stand outside and watch. They were making a huge number of these little pastry packages. Each one was stuffed with what looked like two pieces of raw meat (duck?) sandwiching a stuffing of some kind. I'm guessing the casing was puff pastry, which would puff up and get crisp at the edges when baked.

By the time we finished at Vougeot, it was time and past for lunch, so we set off in search of our usual salads. Unfortunately, the area turns out to be too "gastronomic." Serious restaurants were thick on the ground, but salads and omelets hard to come by. We finally settled on the Millisime (the Vintage) in Chambolle-Mussigny (the next village over from Vougeot) and ordered just one course each. In the little sitting area adjacent to the restaurant was a bookcase displaying copies of the Michelin Restaurant Guide all the way back to 1900!

By the time we finished at Vougeot, it was time and past for lunch, so we set off in search of our usual salads. Unfortunately, the area turns out to be too "gastronomic." Serious restaurants were thick on the ground, but salads and omelets hard to come by. We finally settled on the Millisime (the Vintage) in Chambolle-Mussigny (the next village over from Vougeot) and ordered just one course each. In the little sitting area adjacent to the restaurant was a bookcase displaying copies of the Michelin Restaurant Guide all the way back to 1900!

Amuse-bouche: An absolutely delicious hot green pea soup topped with a smoked-bacon emulsion. Yum.

Amuse-bouche: An absolutely delicious hot green pea soup topped with a smoked-bacon emulsion. Yum.

Main course, David: Cod cooked on the skin, served atop a purée of artichokes, and decorated with very thin, lengthwise slices of asparagus.

Main course, me: Sea scallops seared and then roasted with crumbled pistachios on top, also served atop a purée of artichokes and sided with a strongly vinegar-and-vanilla-flavored caramel sauce.

After lunch (hey, the day was still young), we set off for the Fromagerie Gaugry, which we had seen by the highway on the way south. It was a much larger, more industrial operation than Delin (though extremely proud of its quality control and traditional methods) and was set up for self-guided tours, of the sort where you walk along a hallway peering in through large picture windows at the sealed and nearly sterile environment where the cheese is being made. On a Saturday, not much was going on, but two guys were in there turning the cheeses that had been molded the day before. The signposting and explanations were terrific! I took so many pictures (like every single signpost along the way) that I'll dedicate a special page just to describing that visit.

When we finished at Gaugry, we still had a little time before the Abbey of Cîteaux (the first and original Cistercian monastary) closed for the day, so we headed for that. We could have had a guided tour inside the walls, but it would have run us very late getting back to the hotel, so we just opted for the walk around outside and the 30-minute slide show about life in the abbey. It's housed in modern (i.e. 19th century) buildings (only a few ruins of the original abbey remain), and it's very much a working farm, dairy, and monastary. About 30 monks live there. They divide their time among prayer and study, working on the farm, making their famous (and delicious) cheese, and housekeeping (like making their own clothes, maintaining their own buildings, doing their own laundry, etc.). The French narration of the show was excellent and informative; the English subtitles brief, bland, and platitudinous.

Finally, the day was no longer young, so we headed back to the hotel to get ready for our dinner at the nearby Château de Gilly, where we were entertained during our predinner drink on the terrace by a cute toddler who had a wonderful time running around, picking dandelions, and rummaging in her mother's purse for crackers. On the terrace, David had a kir (1 part black-currant liqueur and 4 parts local white wine, invented, or at least popularized, in Dijon, by a prominent clergyman named Kir) while we munched this beautiful initial amuse-bouche: tiny round blini topped with stewed tomatos, olive slices, and chervil sprigs; minitart shells filled with a mustard mayo, quail-egg halves, tiny shrimp, and dill springs; and spoonfuls of an outstanding cold ratatouille. We also spent some time speculating about why two fire-engine red Ferraris, one with sponsorship stickers all over it, were parked on the parvis in front of the hotel. (One wall of our hotel is decorated with photos of its parking lot, also full of red sports cars, so maybe there's a regular rally here.) Once the kir and yummies were gone, they showed us (and the toddler and her family) to the beautifully vaulted cellar dining room.

Finally, the day was no longer young, so we headed back to the hotel to get ready for our dinner at the nearby Château de Gilly, where we were entertained during our predinner drink on the terrace by a cute toddler who had a wonderful time running around, picking dandelions, and rummaging in her mother's purse for crackers. On the terrace, David had a kir (1 part black-currant liqueur and 4 parts local white wine, invented, or at least popularized, in Dijon, by a prominent clergyman named Kir) while we munched this beautiful initial amuse-bouche: tiny round blini topped with stewed tomatos, olive slices, and chervil sprigs; minitart shells filled with a mustard mayo, quail-egg halves, tiny shrimp, and dill springs; and spoonfuls of an outstanding cold ratatouille. We also spent some time speculating about why two fire-engine red Ferraris, one with sponsorship stickers all over it, were parked on the parvis in front of the hotel. (One wall of our hotel is decorated with photos of its parking lot, also full of red sports cars, so maybe there's a regular rally here.) Once the kir and yummies were gone, they showed us (and the toddler and her family) to the beautifully vaulted cellar dining room.

We chose the top-of-the-line tasting menu, which was surprisingly economical considering the hotel's prices.

Amuse bouche: Cold cream of cockle soup accompanied by a bundle of "wild asparagus" (actually in some other genus, the name of which escapes me just now) with a sweet fruit sauce and a brushstroke of black-currant syrup. Delicious, but difficult to eat—you couldn't get the soup out of such narrow glasses with the tiny spoon supplied without tilting the glass, and the glass was glued to the plate with a splodge of thick sticky sugar syrup (to facilitate serving). I finally twisted mine loose, picked it up, ate the soup, then stuck it back down again.

Amuse bouche: Cold cream of cockle soup accompanied by a bundle of "wild asparagus" (actually in some other genus, the name of which escapes me just now) with a sweet fruit sauce and a brushstroke of black-currant syrup. Delicious, but difficult to eat—you couldn't get the soup out of such narrow glasses with the tiny spoon supplied without tilting the glass, and the glass was glued to the plate with a splodge of thick sticky sugar syrup (to facilitate serving). I finally twisted mine loose, picked it up, ate the soup, then stuck it back down again.

First course: "Beet ravioli" stuffed with lobster, with crustacean vinaigrette, which turned out to be little lobster salads mounded on thin rounds of very sweet cooked beet and covered with additional rounds, to form little unsealed "ravioli," accompanied by small salads and served on top of decorative swirls of balsamic syrup. The plate was additionally decorated with sprouts (which once again looked like alfalfa but were extremely peppery), two pansies, and an orchid (all edible, though I didn't finish my orchid). Excellent.

Second course, squid-ink rissotto with a scallop (the black antennae are uncooked strands of squid-ink spaghetti). Delicious, and quite mild-flavored, but extremely black—our lips and our napkins showed the evidence for some time afterward.

Second course, squid-ink rissotto with a scallop (the black antennae are uncooked strands of squid-ink spaghetti). Delicious, and quite mild-flavored, but extremely black—our lips and our napkins showed the evidence for some time afterward.

Third course: Filets of rouget (little red mullet), sautéed crisp and served with tender stewed fennel and tomatoes and an aniseed emulsion.

Palate cleanser: "Granité au thé vert à la menthe," which the menu translated "Break frozen in the green tea in the mint" but was actually a delicious sorbet of mint and green tea. These serious restaurants spare absolutely no expense, time, or trouble over the food, but they seem to get their translations from Babelfish (or maybe a pencil and a dictionary)! In the preceding dish, the "confit" fennel was translated "candied" fennel. David says I should start a business doing menu translations.

Fourth course: Sautéed filet of veal (pink inside) with fresh morels and asparagus, in a very rich veal reduction.

Cheese course: A selection from this assortment (a rather small collection for a restaurant of this calibre in this region). David chose Brillat-Savarin, Cîteaux, and Comté; I had Brillat-Savarin, Cîteaux, and Puligny-St.-Pierre (the white pyramid at the right, a favorite goat cheese of mine). The Puligny, like all the chevres we've tasted around here, was rather young and dry. The locals ripen their cow cheeses to liquidity (note the three locally made variations on Époisses in their circular wooden boxes; they are served with a spoon) but keep their goat cheeses brittle and chalky (not that I'm complaining; they're still delicious). The Frenchman at the next table chose six cheeses, and the server didn't bat an eye or even seem surprised. Apparently our usual choice of three is rather conservative.

Cheese course: A selection from this assortment (a rather small collection for a restaurant of this calibre in this region). David chose Brillat-Savarin, Cîteaux, and Comté; I had Brillat-Savarin, Cîteaux, and Puligny-St.-Pierre (the white pyramid at the right, a favorite goat cheese of mine). The Puligny, like all the chevres we've tasted around here, was rather young and dry. The locals ripen their cow cheeses to liquidity (note the three locally made variations on Époisses in their circular wooden boxes; they are served with a spoon) but keep their goat cheeses brittle and chalky (not that I'm complaining; they're still delicious). The Frenchman at the next table chose six cheeses, and the server didn't bat an eye or even seem surprised. Apparently our usual choice of three is rather conservative.

Right after the cheeses came the mignardises: skewers of melon balls, pistachio macaroons, and little raspberry tarts with chocolate garnish. The actual dessert was slightly undersweetened fresh raspberry tart, served with a slightly oversweetened (and outstanding) sorbet of red fruits (dominated by strawberry). Together they balanced out perfectly!

Right after the cheeses came the mignardises: skewers of melon balls, pistachio macaroons, and little raspberry tarts with chocolate garnish. The actual dessert was slightly undersweetened fresh raspberry tart, served with a slightly oversweetened (and outstanding) sorbet of red fruits (dominated by strawberry). Together they balanced out perfectly!

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Next, off to Gilly-les-Cîteaux. I have no idea what "Gilly" means, but "Cîteaux" is derived from "cistels" the "reeds" after which the Cistercians are named. Photos we've been shown of "cistels" showed something that's clearly either a grass or a sedge, but wherever we've been proudly shown a commemorative patch of real ones, they've been cattails. Gotta look that one up.

Next, off to Gilly-les-Cîteaux. I have no idea what "Gilly" means, but "Cîteaux" is derived from "cistels" the "reeds" after which the Cistercians are named. Photos we've been shown of "cistels" showed something that's clearly either a grass or a sedge, but wherever we've been proudly shown a commemorative patch of real ones, they've been cattails. Gotta look that one up.

The day was young, so we set out in search of adventure and lunch and found, first of all, this handsome little planting in the "town square" just outside the gates of the château. The Fromagerie Delin is located in Gilly and is highly advertised on the web and in brochures in hotel lobbies for miles around. We could have walked there but took the car because we planned to go further afield afterwards. As I suspected, though, all you can visit is the shop—the actual cheese-making operation is not set up for tours. Delin makes soft, fresh cheeses, fromage blanc, Brillat-Savarin, Fleur de Nuits-St.-George, and a variety of processed cheeses coated with raisins, herbs, or whatnot, as well as crême fraiche, butter, and other small cheeses I've never heard of. They also sell some prominent cheeses made by others, like this Cîteaux, made at the nearby Abbey.

The day was young, so we set out in search of adventure and lunch and found, first of all, this handsome little planting in the "town square" just outside the gates of the château. The Fromagerie Delin is located in Gilly and is highly advertised on the web and in brochures in hotel lobbies for miles around. We could have walked there but took the car because we planned to go further afield afterwards. As I suspected, though, all you can visit is the shop—the actual cheese-making operation is not set up for tours. Delin makes soft, fresh cheeses, fromage blanc, Brillat-Savarin, Fleur de Nuits-St.-George, and a variety of processed cheeses coated with raisins, herbs, or whatnot, as well as crême fraiche, butter, and other small cheeses I've never heard of. They also sell some prominent cheeses made by others, like this Cîteaux, made at the nearby Abbey.

Within the Côtes, the hillsides are divided up into dozens of smaller designations, mostly named for the towns they surround, like Aloxe-Corton and Marsannay and Chambolle-Mussigny. A particularly prestigious designation is "Clos de Vougeot"—it seems the monks at the Abbey of Cîteaux owned land near Nuits-St.-Georges that produced particularly good wine, and they marked out a segment of the region (about 40 ha, I think) that they wanted to acquire all of, and with the persistence of an institution in it for the long term, set about acquiring. In fact, they built a wall around it (the "clos" or enclosure) before they had actually laid hands on all the land inside. On the site, in stages from the 12th to the 16th century, they built a magnificent winery (the Château du Clos de Vougeot) with four huge presses, aging rooms, etc. The view on the left shows the press building from the main courtyard, and the one on the right shows David standing next to the lever shaft of one of the four massive presses (the one nicknamed "the Stubborn"). The press building is square, arranged around a smaller, inner courtyard, and one press occupies each corner. The abbey fell on hard times later, though, and lost ownership of the land. Nowadays, that 40 ha is divided among about 60 owners, all of whom grow grapes and produce wine and all of whom are entitled to the "appellation controlée" (legally protected "brand name") "Clos de Vougeot." The Château is now the worldwide headquarters of the Confrerie des Chevaliers du Tastevin (the Brotherhood of the Cavaliers of Winetasting), which throws elaborate banquets at least annually, presided over by famous people (like royalty, astronauts, etc.), presumably members of the brotherhood. It's open for self-guided tours.

Within the Côtes, the hillsides are divided up into dozens of smaller designations, mostly named for the towns they surround, like Aloxe-Corton and Marsannay and Chambolle-Mussigny. A particularly prestigious designation is "Clos de Vougeot"—it seems the monks at the Abbey of Cîteaux owned land near Nuits-St.-Georges that produced particularly good wine, and they marked out a segment of the region (about 40 ha, I think) that they wanted to acquire all of, and with the persistence of an institution in it for the long term, set about acquiring. In fact, they built a wall around it (the "clos" or enclosure) before they had actually laid hands on all the land inside. On the site, in stages from the 12th to the 16th century, they built a magnificent winery (the Château du Clos de Vougeot) with four huge presses, aging rooms, etc. The view on the left shows the press building from the main courtyard, and the one on the right shows David standing next to the lever shaft of one of the four massive presses (the one nicknamed "the Stubborn"). The press building is square, arranged around a smaller, inner courtyard, and one press occupies each corner. The abbey fell on hard times later, though, and lost ownership of the land. Nowadays, that 40 ha is divided among about 60 owners, all of whom grow grapes and produce wine and all of whom are entitled to the "appellation controlée" (legally protected "brand name") "Clos de Vougeot." The Château is now the worldwide headquarters of the Confrerie des Chevaliers du Tastevin (the Brotherhood of the Cavaliers of Winetasting), which throws elaborate banquets at least annually, presided over by famous people (like royalty, astronauts, etc.), presumably members of the brotherhood. It's open for self-guided tours.

We also admired this well, in another enclosure off the main courtyard. A couple of men pulled on the knotted rope that passed over the large wheel in the back. It turned the smaller wheel over the well (gaining considerable mechanical advantage from the difference in their diameters), raising a bucket out of the well (one much larger than the one full of germaniums). A thick plank fixed to a pivot at one end (on which the geraniums are resting) could then be slid under the bucket to hold it while the bucket was tilted to dump the water into a barrel for transport to the vines. The right-hand photo shows one of the vines just outside the gates, complete with very tiny green grapes.

We also admired this well, in another enclosure off the main courtyard. A couple of men pulled on the knotted rope that passed over the large wheel in the back. It turned the smaller wheel over the well (gaining considerable mechanical advantage from the difference in their diameters), raising a bucket out of the well (one much larger than the one full of germaniums). A thick plank fixed to a pivot at one end (on which the geraniums are resting) could then be slid under the bucket to hold it while the bucket was tilted to dump the water into a barrel for transport to the vines. The right-hand photo shows one of the vines just outside the gates, complete with very tiny green grapes.

At the château, we were able to peer into the "wine library," a room lined with thousands of carefully labeled bottles, presumably of wines produced over the years (centuries?) in the clos. The fermenting and aging rooms have been redone as meeting space for the brotherhood. When we were there, one section of the pressing room was set up as an auditorium (I took this photo of David from the speaker's stand, with my back to "the Stubborn"; you can see the lever shaft of another of the presses against the back wall). Another room was set up with banquet tables, and to our delight, the kitchens were busy preparing for some sort of gala dinner! The doors and windows were wide open, so we were able to stand outside and watch. They were making a huge number of these little pastry packages. Each one was stuffed with what looked like two pieces of raw meat (duck?) sandwiching a stuffing of some kind. I'm guessing the casing was puff pastry, which would puff up and get crisp at the edges when baked.

At the château, we were able to peer into the "wine library," a room lined with thousands of carefully labeled bottles, presumably of wines produced over the years (centuries?) in the clos. The fermenting and aging rooms have been redone as meeting space for the brotherhood. When we were there, one section of the pressing room was set up as an auditorium (I took this photo of David from the speaker's stand, with my back to "the Stubborn"; you can see the lever shaft of another of the presses against the back wall). Another room was set up with banquet tables, and to our delight, the kitchens were busy preparing for some sort of gala dinner! The doors and windows were wide open, so we were able to stand outside and watch. They were making a huge number of these little pastry packages. Each one was stuffed with what looked like two pieces of raw meat (duck?) sandwiching a stuffing of some kind. I'm guessing the casing was puff pastry, which would puff up and get crisp at the edges when baked. By the time we finished at Vougeot, it was time and past for lunch, so we set off in search of our usual salads. Unfortunately, the area turns out to be too "gastronomic." Serious restaurants were thick on the ground, but salads and omelets hard to come by. We finally settled on the Millisime (the Vintage) in Chambolle-Mussigny (the next village over from Vougeot) and ordered just one course each. In the little sitting area adjacent to the restaurant was a bookcase displaying copies of the Michelin Restaurant Guide all the way back to 1900!

By the time we finished at Vougeot, it was time and past for lunch, so we set off in search of our usual salads. Unfortunately, the area turns out to be too "gastronomic." Serious restaurants were thick on the ground, but salads and omelets hard to come by. We finally settled on the Millisime (the Vintage) in Chambolle-Mussigny (the next village over from Vougeot) and ordered just one course each. In the little sitting area adjacent to the restaurant was a bookcase displaying copies of the Michelin Restaurant Guide all the way back to 1900! Amuse-bouche: An absolutely delicious hot green pea soup topped with a smoked-bacon emulsion. Yum.

Amuse-bouche: An absolutely delicious hot green pea soup topped with a smoked-bacon emulsion. Yum.

Finally, the day was no longer young, so we headed back to the hotel to get ready for our dinner at the nearby Château de Gilly, where we were entertained during our predinner drink on the terrace by a cute toddler who had a wonderful time running around, picking dandelions, and rummaging in her mother's purse for crackers. On the terrace, David had a kir (1 part black-currant liqueur and 4 parts local white wine, invented, or at least popularized, in Dijon, by a prominent clergyman named Kir) while we munched this beautiful initial amuse-bouche: tiny round blini topped with stewed tomatos, olive slices, and chervil sprigs; minitart shells filled with a mustard mayo, quail-egg halves, tiny shrimp, and dill springs; and spoonfuls of an outstanding cold ratatouille. We also spent some time speculating about why two fire-engine red Ferraris, one with sponsorship stickers all over it, were parked on the parvis in front of the hotel. (One wall of our hotel is decorated with photos of its parking lot, also full of red sports cars, so maybe there's a regular rally here.) Once the kir and yummies were gone, they showed us (and the toddler and her family) to the beautifully vaulted cellar dining room.

Finally, the day was no longer young, so we headed back to the hotel to get ready for our dinner at the nearby Château de Gilly, where we were entertained during our predinner drink on the terrace by a cute toddler who had a wonderful time running around, picking dandelions, and rummaging in her mother's purse for crackers. On the terrace, David had a kir (1 part black-currant liqueur and 4 parts local white wine, invented, or at least popularized, in Dijon, by a prominent clergyman named Kir) while we munched this beautiful initial amuse-bouche: tiny round blini topped with stewed tomatos, olive slices, and chervil sprigs; minitart shells filled with a mustard mayo, quail-egg halves, tiny shrimp, and dill springs; and spoonfuls of an outstanding cold ratatouille. We also spent some time speculating about why two fire-engine red Ferraris, one with sponsorship stickers all over it, were parked on the parvis in front of the hotel. (One wall of our hotel is decorated with photos of its parking lot, also full of red sports cars, so maybe there's a regular rally here.) Once the kir and yummies were gone, they showed us (and the toddler and her family) to the beautifully vaulted cellar dining room.

Amuse bouche: Cold cream of cockle soup accompanied by a bundle of "wild asparagus" (actually in some other genus, the name of which escapes me just now) with a sweet fruit sauce and a brushstroke of black-currant syrup. Delicious, but difficult to eat—you couldn't get the soup out of such narrow glasses with the tiny spoon supplied without tilting the glass, and the glass was glued to the plate with a splodge of thick sticky sugar syrup (to facilitate serving). I finally twisted mine loose, picked it up, ate the soup, then stuck it back down again.

Amuse bouche: Cold cream of cockle soup accompanied by a bundle of "wild asparagus" (actually in some other genus, the name of which escapes me just now) with a sweet fruit sauce and a brushstroke of black-currant syrup. Delicious, but difficult to eat—you couldn't get the soup out of such narrow glasses with the tiny spoon supplied without tilting the glass, and the glass was glued to the plate with a splodge of thick sticky sugar syrup (to facilitate serving). I finally twisted mine loose, picked it up, ate the soup, then stuck it back down again. Second course, squid-ink rissotto with a scallop (the black antennae are uncooked strands of squid-ink spaghetti). Delicious, and quite mild-flavored, but extremely black—our lips and our napkins showed the evidence for some time afterward.

Second course, squid-ink rissotto with a scallop (the black antennae are uncooked strands of squid-ink spaghetti). Delicious, and quite mild-flavored, but extremely black—our lips and our napkins showed the evidence for some time afterward.

Cheese course: A selection from this assortment (a rather small collection for a restaurant of this calibre in this region). David chose Brillat-Savarin, Cîteaux, and Comté; I had Brillat-Savarin, Cîteaux, and Puligny-St.-Pierre (the white pyramid at the right, a favorite goat cheese of mine). The Puligny, like all the chevres we've tasted around here, was rather young and dry. The locals ripen their cow cheeses to liquidity (note the three locally made variations on Époisses in their circular wooden boxes; they are served with a spoon) but keep their goat cheeses brittle and chalky (not that I'm complaining; they're still delicious). The Frenchman at the next table chose six cheeses, and the server didn't bat an eye or even seem surprised. Apparently our usual choice of three is rather conservative.

Cheese course: A selection from this assortment (a rather small collection for a restaurant of this calibre in this region). David chose Brillat-Savarin, Cîteaux, and Comté; I had Brillat-Savarin, Cîteaux, and Puligny-St.-Pierre (the white pyramid at the right, a favorite goat cheese of mine). The Puligny, like all the chevres we've tasted around here, was rather young and dry. The locals ripen their cow cheeses to liquidity (note the three locally made variations on Époisses in their circular wooden boxes; they are served with a spoon) but keep their goat cheeses brittle and chalky (not that I'm complaining; they're still delicious). The Frenchman at the next table chose six cheeses, and the server didn't bat an eye or even seem surprised. Apparently our usual choice of three is rather conservative. Right after the cheeses came the mignardises: skewers of melon balls, pistachio macaroons, and little raspberry tarts with chocolate garnish. The actual dessert was slightly undersweetened fresh raspberry tart, served with a slightly oversweetened (and outstanding) sorbet of red fruits (dominated by strawberry). Together they balanced out perfectly!

Right after the cheeses came the mignardises: skewers of melon balls, pistachio macaroons, and little raspberry tarts with chocolate garnish. The actual dessert was slightly undersweetened fresh raspberry tart, served with a slightly oversweetened (and outstanding) sorbet of red fruits (dominated by strawberry). Together they balanced out perfectly!