Wednesday, 17 June 2009, Palace, safari, Corsica!

Written 22 June 2009

Wednesday, we had afternoon reservations for a Safari Tour of the vinyards (alas, the Office de Tourisme no longer has the personnel to organize the great half-day bus excursions they used to do, so a private company has taken up the slack), so we set off to spend the morning in the city's Wine Museum, which is housed in the local palace (actually, more of an urban castle) of the Ducs de Bourgogne. On the way, we passed through this small produce market (taking place, appropriately enough, in the Place du Marché). As usual, the fruits and vegetables were much better looking than those available in Tallahassee. Another vegetable stand had leeks in two sizes—the usual large ones and tiny, baby ones. only a little bigger than scallions. Other stands sold hand-made soap, dried fruit, honey products, etc. No meat, fish, cheese, or hardware. That stuff would appear on Saturdays at the big, official weekly market.

Wednesday, we had afternoon reservations for a Safari Tour of the vinyards (alas, the Office de Tourisme no longer has the personnel to organize the great half-day bus excursions they used to do, so a private company has taken up the slack), so we set off to spend the morning in the city's Wine Museum, which is housed in the local palace (actually, more of an urban castle) of the Ducs de Bourgogne. On the way, we passed through this small produce market (taking place, appropriately enough, in the Place du Marché). As usual, the fruits and vegetables were much better looking than those available in Tallahassee. Another vegetable stand had leeks in two sizes—the usual large ones and tiny, baby ones. only a little bigger than scallions. Other stands sold hand-made soap, dried fruit, honey products, etc. No meat, fish, cheese, or hardware. That stuff would appear on Saturdays at the big, official weekly market.

From there, we turned up the Rue de Paradis (Paradise Street) to what was originally the back door of the Duc de Bourgogne's Beaune townhouse, which now houses the Wine Museum. Inside, we were greeted by the famous Notre Dame de Beaune (otherwise known as the Madonna of the Bunch of Grapes). Like all the museums we've visited, this one was extremely edifying—museumship (museumcraft?) has improved enormously since we were dragged as children through room after room of dusty stuff will little labels on it. It included extensive displays about wine-label art and the ways it has changed over the centuries; the lives of winemakers through history (including an ornate hurdy-gurdy, a chubby stringed instrument, like an extremely foreshortened lute or mandolin, with a crank on the side; it was apparently the common source of music at parties and celebrations); an early-20th-century photograph of three naked men jumping into a vat of already pressed wine to "turn the cap" (mix the floating mass of skins, seeds, and stems back into the liquid below, to encourage development of a good red color); and a great selection of wine-makers' proverbs: "Vigne grélée, vigne fumée" ("A vine hailed on is a smoked vine"—'fraid I don't understand that one; I've been looking for someone who can tell me what a "smoked vine" is); "S'il tonne en mars, le vigneron se lasse " ("If it thunders in March, the winemaker relaxes"; because everything will be okay, I guess?); "Si tu tailles en février, tu mets du raisin dans ton panier" ("If you prune in February, you put grapes in your basket"; that one's clearer); "La brise nourit la Bourgogne; le vent du Morvan l'affame" ("The breeze nourishes Burgundy; the wind from the Morvan, i.e., from the west, starves it"); "Pluie de février vaut du fumier" (another ambiguous one: "Rain in February is worth [um...] manure"; does that mean "is worthless" or "is as good as fertilizer"?); "La pluie de St. Médard diminue la vendange d'un quart" ("Rain on St. Médard's day [whenever that is] reduces the harvest by a quarter") ; "Tonnerre d'avril replit les barrils" ("Thunder in April fills the barrels"); "De St. Paul le temps clair et beau annonce plus de vin que d'eau" ("Fine weather at St. Paul's day [whenever that is] portends more wine than water").

From there, we turned up the Rue de Paradis (Paradise Street) to what was originally the back door of the Duc de Bourgogne's Beaune townhouse, which now houses the Wine Museum. Inside, we were greeted by the famous Notre Dame de Beaune (otherwise known as the Madonna of the Bunch of Grapes). Like all the museums we've visited, this one was extremely edifying—museumship (museumcraft?) has improved enormously since we were dragged as children through room after room of dusty stuff will little labels on it. It included extensive displays about wine-label art and the ways it has changed over the centuries; the lives of winemakers through history (including an ornate hurdy-gurdy, a chubby stringed instrument, like an extremely foreshortened lute or mandolin, with a crank on the side; it was apparently the common source of music at parties and celebrations); an early-20th-century photograph of three naked men jumping into a vat of already pressed wine to "turn the cap" (mix the floating mass of skins, seeds, and stems back into the liquid below, to encourage development of a good red color); and a great selection of wine-makers' proverbs: "Vigne grélée, vigne fumée" ("A vine hailed on is a smoked vine"—'fraid I don't understand that one; I've been looking for someone who can tell me what a "smoked vine" is); "S'il tonne en mars, le vigneron se lasse " ("If it thunders in March, the winemaker relaxes"; because everything will be okay, I guess?); "Si tu tailles en février, tu mets du raisin dans ton panier" ("If you prune in February, you put grapes in your basket"; that one's clearer); "La brise nourit la Bourgogne; le vent du Morvan l'affame" ("The breeze nourishes Burgundy; the wind from the Morvan, i.e., from the west, starves it"); "Pluie de février vaut du fumier" (another ambiguous one: "Rain in February is worth [um...] manure"; does that mean "is worthless" or "is as good as fertilizer"?); "La pluie de St. Médard diminue la vendange d'un quart" ("Rain on St. Médard's day [whenever that is] reduces the harvest by a quarter") ; "Tonnerre d'avril replit les barrils" ("Thunder in April fills the barrels"); "De St. Paul le temps clair et beau annonce plus de vin que d'eau" ("Fine weather at St. Paul's day [whenever that is] portends more wine than water").

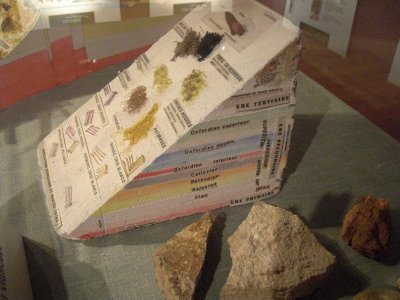

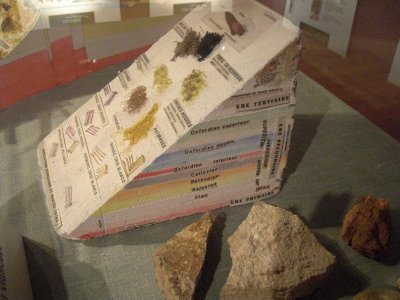

The museum had particularly extensive (and sometimes rather technical) sections on the geology and meteorology of the Côte d'Or, including (among many others) these two models. The displays explain many differences between the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune, making clear that the boundary between them is not arbitrary—for example, the former is an anticline, the latter a syncline, and they face slightly different directions, therefore receiving slightly different sun exposure. Really interesting. [Dan: If you'd like more detail, I have many more photos of the displays and explanatory panels on the geology—sorry, not very volcanic.]

The museum had particularly extensive (and sometimes rather technical) sections on the geology and meteorology of the Côte d'Or, including (among many others) these two models. The displays explain many differences between the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune, making clear that the boundary between them is not arbitrary—for example, the former is an anticline, the latter a syncline, and they face slightly different directions, therefore receiving slightly different sun exposure. Really interesting. [Dan: If you'd like more detail, I have many more photos of the displays and explanatory panels on the geology—sorry, not very volcanic.]

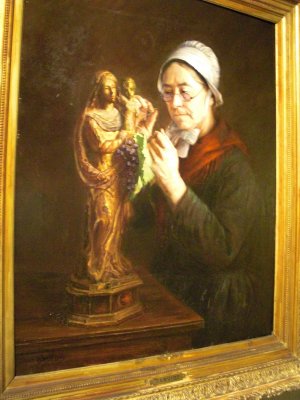

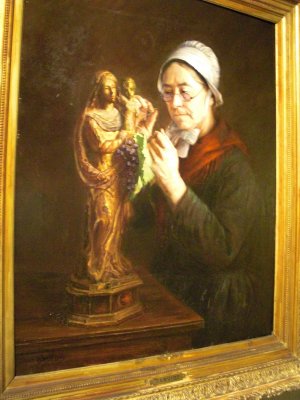

Like most wine museums, this one includes an extensive section on barrel-making (apparently anybody can make a bottle—bottle shapes are sometimes discussed, but the manufacture is never mentioned, whereas barrel making remains a highly skilled craft, and even modern barrels cost thousands of dollars and must be replaced every three years or so). We watched an excellent video on the construction of barrels entirely by hand, then a briefer one on modern barrel making—it's still done mostly by hand, but, for example, the staves are moved (by hand) over a power planer rather than shaped with a hand-powered plane. The exhibit ended with this display of miniature barrels and wine presses constructed inside wine bottles (together with some of the tools used to construct them—the inland equivalent of ships in a bottle. At the right is a painting of a local tradition—tying a bunch of grapes onto the household's statue of the virgin Mary, in hopes of a successful harvest and vinification.

Like most wine museums, this one includes an extensive section on barrel-making (apparently anybody can make a bottle—bottle shapes are sometimes discussed, but the manufacture is never mentioned, whereas barrel making remains a highly skilled craft, and even modern barrels cost thousands of dollars and must be replaced every three years or so). We watched an excellent video on the construction of barrels entirely by hand, then a briefer one on modern barrel making—it's still done mostly by hand, but, for example, the staves are moved (by hand) over a power planer rather than shaped with a hand-powered plane. The exhibit ended with this display of miniature barrels and wine presses constructed inside wine bottles (together with some of the tools used to construct them—the inland equivalent of ships in a bottle. At the right is a painting of a local tradition—tying a bunch of grapes onto the household's statue of the virgin Mary, in hopes of a successful harvest and vinification.

Just before the exit, we passed through this display of three modern tapestries—the photo shows an entire small one and about a third of a large one (the third was intermediate in size, an abstract in shades of red, gold, and brown).

Just before the exit, we passed through this display of three modern tapestries—the photo shows an entire small one and about a third of a large one (the third was intermediate in size, an abstract in shades of red, gold, and brown).

We left the museum through the original front gate of the ducal townhouse and continued on to have a look at the town's main church, the Basilique de Notre Dame, and its peaceful cloister. The complex is a daughter house of the Abbey at Cluny and dates from about 1120. In the choir is displayed a famous black madonna and tapestries protraying the life of the virgin, but that section was closed for lunch when we were there—you can walk around the rest of the church by yourself, but that section is always guarded, and a sign warns you not to rattle the gate, lest you set off the burglar alarm.

We left the museum through the original front gate of the ducal townhouse and continued on to have a look at the town's main church, the Basilique de Notre Dame, and its peaceful cloister. The complex is a daughter house of the Abbey at Cluny and dates from about 1120. In the choir is displayed a famous black madonna and tapestries protraying the life of the virgin, but that section was closed for lunch when we were there—you can walk around the rest of the church by yourself, but that section is always guarded, and a sign warns you not to rattle the gate, lest you set off the burglar alarm.

Finally, on the way back toward the tourist office (where our wine tour would start), and in search of lunch, we passed by the "beffroi" (belfry; I'm not sure how it differs from a "clocher") of Philippe le Bon. The street next to it is so narrow you can't even see it from below, and from here in the Place Marey, the trees are in the way, so this is about the best view you can get.

Finally, on the way back toward the tourist office (where our wine tour would start), and in search of lunch, we passed by the "beffroi" (belfry; I'm not sure how it differs from a "clocher") of Philippe le Bon. The street next to it is so narrow you can't even see it from below, and from here in the Place Marey, the trees are in the way, so this is about the best view you can get.

We found lunch at the Baltard Café, back in the Place du Marché, but I forgot to photograph it. I had a cheese and ham omelet with salad on the side (the chef had added a little cornstarch to the eggs, so they formed a tasty crispy crust without being overcooked on the inside). David had another plate of jambon persillée. The market was almost over, but right across from our sidewalk table was a small fruit stand that I was able to watch while we ate. The vendor had two grades of cherries (labeled categories I and II), and he was offering samples of both. During our lunch three different people showed up and tasted both kinds, and all three then bought category I. Accordingly, I passed on dessert and, while David settled our lunch check, I walked over and bought 100 g of category I cherries, which were huge. On impulse, I also bought one apricot—they were small and fragrant, with a beautiful red blush on one side—and the vendor threw in a second, so as to round the total price up to 50 eurocents, which I paid happily. I munched the cherries, which were great, as we strolled toward the tourist office. The apricots smelled delicious but were still a bit firm, so I rolled them up in their little paper bag and put them in my purse for later.

The tour was in an eight-passenger van, but only one other couple had signed up—the Lucases. The guide was already surprised to learn that we preferred the tour in French, and when Mrs. Lucas turned out to have spent her childhood in France and to speak essentially native French, he pronounced himself astonished—a group of four Americans, and three of them spoke French! Next he introduced himself—he's usually called "Lou-Lou," short for his name, Loïc, which means "little Louis"—explaining how unusual the name is, even in France, and was astonished again when we said we knew two others (a colleague in Brittany and the four-year-old son of a colleague in Tallahassee), knew it was a Breton name, how to spell it, and everything. He turned out to be a great guide—gregarious, outgoing, and speaking excellent English—the ideal sort of person to lead these tours. He was also extremely knowledgeable; he grew up in this area, in Savigny-les-Beaune, where he father tried to make a go of wine-making, but the family's plot was just too small for profitability. Before they got out of the business, though, Loïc worked at every aspect of it.

He started by driving us south out of Beaune and through Pommard (a typical Burgundian village, he said—600 inhabitants, 42 wine companies), then stopping out in the vines. He explained that these green grapes are gigantic for the time of year. The area has had lots of rain, so most of the vines set too many clusters, and the grapes are getting big very fast. Soon someone will come around and cut off all but about eight clusters per vine, retaining the most promising ones and especially those low on the plant. The vines in Burgundy are pruned very severely and kept quite small in comparison with those of other regions. Note, in the right-hand photo the different patches of vines, some older, some younger, divided by narrow bare strips by by stone walls. All of these plots are probably owned by different people. Across the road, Loïc pointed out a patch six rows wide and perhaps 100 m long that had been recently replanted and explained that it belonged to a different owner than the plots on either side. No markings indicate changes of ownership, he explained, but everyone in the area knows just who owns which rows.

He started by driving us south out of Beaune and through Pommard (a typical Burgundian village, he said—600 inhabitants, 42 wine companies), then stopping out in the vines. He explained that these green grapes are gigantic for the time of year. The area has had lots of rain, so most of the vines set too many clusters, and the grapes are getting big very fast. Soon someone will come around and cut off all but about eight clusters per vine, retaining the most promising ones and especially those low on the plant. The vines in Burgundy are pruned very severely and kept quite small in comparison with those of other regions. Note, in the right-hand photo the different patches of vines, some older, some younger, divided by narrow bare strips by by stone walls. All of these plots are probably owned by different people. Across the road, Loïc pointed out a patch six rows wide and perhaps 100 m long that had been recently replanted and explained that it belonged to a different owner than the plots on either side. No markings indicate changes of ownership, he explained, but everyone in the area knows just who owns which rows.

All the vinyards in Burgundy are divided into four immutable grades—in the Côte d'Or area, they are, in order of increasing quality, "Bourgogne," "Village," "Premier cru," and "Grand cru." These distinctions have been made for centuries (the Cistercian monks had sorted them out by the time they were assembling the Clos de Vougeot in the 12th century), but they were only written into law about a hundred years ago. The designations are strictly geographic, with sharp, legally defined boundaries, and additional rules govern what can and/or must go on the wine labels. Every bottle of French burgundy will bear the word "Bourgogne" (the region) and the name of the maker or broker. If that's all, then its from the lowest grade (probably down on the flats near the road); legally, it could be from a higher grade, but no winemaker would fail to say so if it were. If it's from a better grade, then "Village," "Premier cru," or "Grand cru" will appear on the label, and if it does, then you can be assured that every single grape in the bottle was harvested from land graded at least that high. Especially at the higher levels, it will also bear the name of the village it was grown near (like "Pommard" or "Meursault"; again the boundaries are very strict) and, if it's something special, also the name of the parcel of land it was grown on (like "Clos de Vougeot" or "Les Peuillets"). Laws also govern details like how many hectoliters of wine can be produced per hectare, how the grapes are grown, how they are handled after harvest, etc. Within each parcel of land, many owners may own plots, so different makers may produce wine labeled "Premier cru, les Peuillets" ("Les Peuillets" is a designated parcel of land, divided among many owners, but all within the "Premier cru" designation).

As in Champagne, the serious annual pruning that shapes the growth of the vine is done by hand, in winter. Now, in June, mid-season trimming is being done by machine. Tractors that span the rows just trim them off to a certain height and width. The vines are much older than the ones we toured last year. Those in Champagne are ripped out and replaced every 30 years or so, because to make good champagne, you need very acidic grapes, and older vines produce less acid—only a few older vines are retained as a source of grafting material (all vines in both regions are grafted on American rootstocks, the only ones resistant to Phylloxera, a sapsucking insect that soon kills native rootstocks). In Burgundy, in contrast, vines are not even harvested until they reach 5 years old, then the philosophy is "the older the better." To carry the notation "vieilles vignes" (old vines), like a glass David enjoyed at a recent dinner, the wine must come from vines at least 50 years old. Loïc showed us the oldest vines he knows of, which are 115 years old (90 is more usual for very old vines, but of course the age of vines now alive is limited by the advent of Phylloxera in the late 19th century; none survive from before that).

Standing on a hillside overlooking the vinyards below, then some vinyards on the flat, then the D974, then a few vines beyond, he explained property values. Over there beyond the road, you could buy land, say a building lot, for about 25,000 euros/ha. On the flat on this side of the road, the price would be more like 500,000 euros/ha. Up on the slopes, you'd be talking about 1-1.5 million euros/ha, and in a plot designated "premier cru" (very good) or "grand cru" (the best), the price is simply astronomical— many millions. Locals were astonished when someone recently sold such a plot, not at the price he got but that he would consider selling—as Loïc put it, you sell the land for 25 million euros, the government takes half, then you and your descendents spend the money, and you're left with nothing; the land would have been a gold mine forever! Burgundians are fanatics about care of the land. Every spring, they scrape up the soil that has washed down the hill (where it collects against the first stone wall it encounters) and carry it back up to the top (Loïc shook his head at the memory of carrying baskets of dirt up a vinyard of his father's so steep it couldn't accommodate tractors—in some vinyards, the trimmers and cultivators are still pulled by horses). Selling a plot is like selling a child. While we had them in view, I asked why the vines were so yellow in patches; were they short of iron? He explained that they had recently had a few very hot days, which will tend to yellow the vines. Persistently yellow plots might be given iron supplements, but a small, very yellow patch in the middle of a an otherwise healthy plot is a sign of an incurable fungal disease. Those vines and those immediately next to them must be ripped out and the soil rested for about five years before new vines are planted.

The grapes are harvested by hand, but machine-harvesting companies exist, because labor is in such high demand at harvest time. Loïc said that, when you need 20 pickers and you can only get 15, you assign them to your higher-value plots, then call in the machines to do the lower-value ones down on the flat that you can't get around to.

He also talked about a third variety of grape grown in Burgundy, the "aligoté," the wines from which travel poorly and are almost unknown outside the region. It's a white grape grown on ground unsuitable for the more usual Chardonnay. A proper kir, as originally concocted by the mayor of Dijon, calls for 1 part crême de cassis and 4 parts Burgundy aligoté, but outside Burgundy kirs are now made with just any old white wine. I know that "aligot" is mashed potatoes beaten with cheese and garlic; I have no idea what that has to do with "aligoté," which should mean "coated or flavored with aligot."

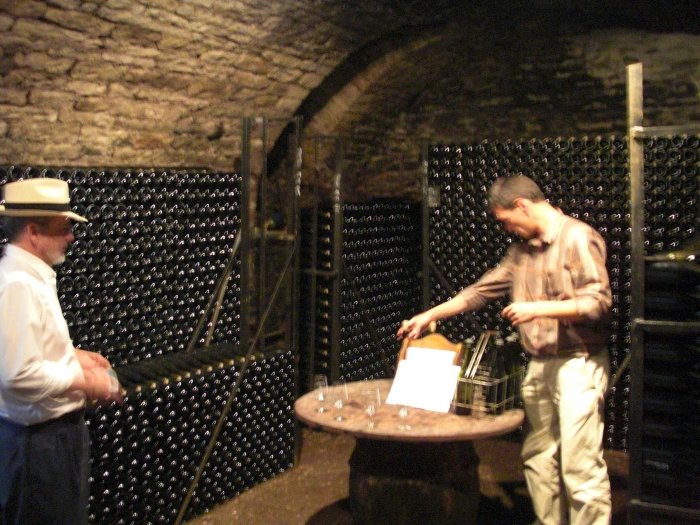

After Pommard, Volnay, and Monthélie, we stopped in Meursault to view the Town Hall, which was featured in a famous comic film called La Grande Vandrouille (the name means "the great wandering-around" but it is rendered into English as Don't Look Now: We're Being Shot At; we saw a mural in Beaune depicting the making of the film, which also used locations there). Our tour continued through Bouze les Beaune and ended in Savigny-les-Beaune, where Loïc grew up. He took us to the Domaine Serrigny, owned and operated by two young women, Francine and Marie-Laure Serrigny (elementary-school classmates of his). They are the youngest of four daughters in a family without sons and have decided to carry on their father's business. They own 7 ha (ca. 15 acres) of vines, but as it typical of the area, their holdings are not contiguous. They own two plots in "premier cru" areas, from which they could, if they wished, combine the harvest and label the resulting wine "Savigny-les-Beaune premier cru," but the wines from the two have slightly different character, so they keep them separate and label them by their "neighborhoods" within the premier cru—"La Dominode" and "Les Peuillets." Other areas they own are also planted with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, or Aligoté, so in all they produce seven different wines, four reds (including the two premier crus), and three whites of different designations. In all, they produce about 35,000 bottles a year. I didn't ask whether they bottle the wines themselves, by hand, or whether they call in a mechanized bottling company (running a robotic bottling line is considered the work of specialists—it has to be kept perfectly oiled and adjusted—so many winemakers who would use one only, say, two days a year just call in the experts, who park their truck-mounted line in the courtyard and run a hose into the barrels in the cellar), but they hand-paste all 35,000 labels themselves.

After Pommard, Volnay, and Monthélie, we stopped in Meursault to view the Town Hall, which was featured in a famous comic film called La Grande Vandrouille (the name means "the great wandering-around" but it is rendered into English as Don't Look Now: We're Being Shot At; we saw a mural in Beaune depicting the making of the film, which also used locations there). Our tour continued through Bouze les Beaune and ended in Savigny-les-Beaune, where Loïc grew up. He took us to the Domaine Serrigny, owned and operated by two young women, Francine and Marie-Laure Serrigny (elementary-school classmates of his). They are the youngest of four daughters in a family without sons and have decided to carry on their father's business. They own 7 ha (ca. 15 acres) of vines, but as it typical of the area, their holdings are not contiguous. They own two plots in "premier cru" areas, from which they could, if they wished, combine the harvest and label the resulting wine "Savigny-les-Beaune premier cru," but the wines from the two have slightly different character, so they keep them separate and label them by their "neighborhoods" within the premier cru—"La Dominode" and "Les Peuillets." Other areas they own are also planted with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, or Aligoté, so in all they produce seven different wines, four reds (including the two premier crus), and three whites of different designations. In all, they produce about 35,000 bottles a year. I didn't ask whether they bottle the wines themselves, by hand, or whether they call in a mechanized bottling company (running a robotic bottling line is considered the work of specialists—it has to be kept perfectly oiled and adjusted—so many winemakers who would use one only, say, two days a year just call in the experts, who park their truck-mounted line in the courtyard and run a hose into the barrels in the cellar), but they hand-paste all 35,000 labels themselves.

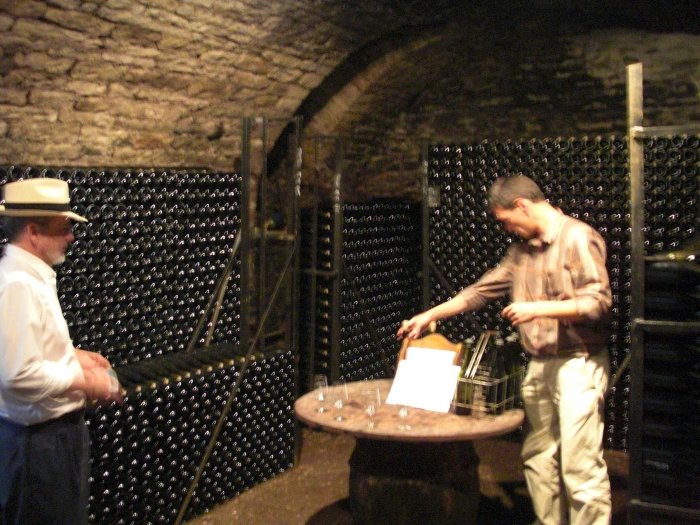

Apparently, they're doing okay on their 7 ha, so Loïc's father's holdings must have been smaller—the hard part is that they're doing the whole thing alone (pruning, trimming, wire lifting, spraying, inspection, crushing, cap-turning, vinifying, bottling, labeling, and sales, without hired help except for the harvest, and holdings that size really call for three or even four people. Even though the sign on their gate says "tasting and sales," no one was there when we were—they were out in the vines trimming and lifting wires, so we could only taste because Loïc has a key to the place. We had our tastes in the smallest of their three cellars, which holds about 10,000 bottles.

Apparently, they're doing okay on their 7 ha, so Loïc's father's holdings must have been smaller—the hard part is that they're doing the whole thing alone (pruning, trimming, wire lifting, spraying, inspection, crushing, cap-turning, vinifying, bottling, labeling, and sales, without hired help except for the harvest, and holdings that size really call for three or even four people. Even though the sign on their gate says "tasting and sales," no one was there when we were—they were out in the vines trimming and lifting wires, so we could only taste because Loïc has a key to the place. We had our tastes in the smallest of their three cellars, which holds about 10,000 bottles.

Written 25 June 2009/p>

Loïc reminisced about turning the cap in his father's fermentation vats. Apparently, Burgundy grapes haven't been initially crushed "by foot" since the discovery of the lever—the grapes are quite hard at harvest— but even today, the cap is often turned that way. After the grapes are crushed, and the mixture of juice, pulp, seeds, skins, and stem is then dumped into a vat for the initial fermentation, the solids float to the top and form a layer that gels pretty solidly—firm enough, if you've left even a modest amount of stem attached to the grapes, to walk on. That gelled cap must be turned over and broken up so that the color from the skins can leach properly into the juice. The easiest and most practical method, at least for small producers, is to remove the shoes, socks, and long trousers and to push and shove with the feet. The practice can be dangerous—turning the cap liberates great waves of carbon dioxide (one breath can severly damage the lungs and a couple can kill an adult)—so they never work alone, and before they begin, the winemakers set up a tall narrow set of shelves with a candle on each shelf, and someone stands by with a big fan. The candles warn of the amount of CO2 accumulating on the floor—successive candles go out as the level rises. The guy with the fan leaps to the rescue of anyone who loses his balance and falls into the pool of CO2 (or the vat).

Loïc reminisced about turning the cap in his father's fermentation vats. Apparently, Burgundy grapes haven't been initially crushed "by foot" since the discovery of the lever—the grapes are quite hard at harvest— but even today, the cap is often turned that way. After the grapes are crushed, and the mixture of juice, pulp, seeds, skins, and stem is then dumped into a vat for the initial fermentation, the solids float to the top and form a layer that gels pretty solidly—firm enough, if you've left even a modest amount of stem attached to the grapes, to walk on. That gelled cap must be turned over and broken up so that the color from the skins can leach properly into the juice. The easiest and most practical method, at least for small producers, is to remove the shoes, socks, and long trousers and to push and shove with the feet. The practice can be dangerous—turning the cap liberates great waves of carbon dioxide (one breath can severly damage the lungs and a couple can kill an adult)—so they never work alone, and before they begin, the winemakers set up a tall narrow set of shelves with a candle on each shelf, and someone stands by with a big fan. The candles warn of the amount of CO2 accumulating on the floor—successive candles go out as the level rises. The guy with the fan leaps to the rescue of anyone who loses his balance and falls into the pool of CO2 (or the vat).

After a terrific tour (on the way back, we passed this whimsical ice house; no one seems to know why it has a cute, crenelated tower), Loïc brought us back to the Office de Tourism. We had time before dinner, so we walked a few blocks to two antequarian bookstores David had spotted, but always during the lunchtime closure. As always, it was fun to browse the old books, but we didn't find anything we couldn't live without.

Dinner was at Le Jardin des Remparts, and back in March, when I made the reservation, the management had explained that the evening we had chosen was already scheduled for a special dinner, which we were welcome to join, but the menu would be set, and the whole thing would feature the wines of Corsica. Okay, we were fine with that, so we signed up. When we arrived at the restaurant, which has a lovely fenced and walled garden in front, we found a full-scale garden party in progress (though the dress code was not necessarily that approved by the queen; if anything, we were a bit overdressed).

Dinner was at Le Jardin des Remparts, and back in March, when I made the reservation, the management had explained that the evening we had chosen was already scheduled for a special dinner, which we were welcome to join, but the menu would be set, and the whole thing would feature the wines of Corsica. Okay, we were fine with that, so we signed up. When we arrived at the restaurant, which has a lovely fenced and walled garden in front, we found a full-scale garden party in progress (though the dress code was not necessarily that approved by the queen; if anything, we were a bit overdressed).

We presented ourselves to one of the staff as the American tourists who had stumbled into the affair, and soon Madame the hostess and her husband the chef, who were mingling with the guests, came over to introduce themselves, welcome us, and suggest that we not be shy about making friends with the others, most of whom were regulars at the restaurant. The dinner was to be accompanied by the wines of Antoine Arena (that's him in the blue shirt under the left-most white umbrella above), a Corsican winemaker. We never got straight how he and the restaurant were connected.

We presented ourselves to one of the staff as the American tourists who had stumbled into the affair, and soon Madame the hostess and her husband the chef, who were mingling with the guests, came over to introduce themselves, welcome us, and suggest that we not be shy about making friends with the others, most of whom were regulars at the restaurant. The dinner was to be accompanied by the wines of Antoine Arena (that's him in the blue shirt under the left-most white umbrella above), a Corsican winemaker. We never got straight how he and the restaurant were connected.

Several kinds of cocktail munchies were being passed, to accompany the first wine. In addition to these (little melon-juice "magic balls," quail's eggs on tomato sauce, jellied beef consommé with something on top, seafood custard with diced raw fish on top), we were offered cromesquis of pigs' trotters (very "in" right now), platters of shaved raw ham and salami, and spoonfuls of mussel-and-saffron sorbet. (With the munchies, Blanc Cépage Vermentinu Cuvée Hauts de Carco 2008.)

We were curious as to whether we would be seated at large, communal tables, but no, apparently all the other guests had signed up as groups, so an individual table was set for each group, from large round ones for eight to several for couples, like us. Each of us received a little printed copy of the menu to keep.

First course, "raw grilled langoustines": We were puzzled by that description, but sure enough, we each got a plate of sliced raw langoustine tails that had a delicious grilled-seafood flavor! They were accompanied by a little mound of savory rice pudding studded with crisp black and red crêpe strips. The results were absolutely delicious, but we were baffled. Finally, we asked our waitress, who revealed that the chef grilled a bunch of langoustines, then dressed the raw ones with the resulting grilled-langoustine oil. What a great idea! (With the langoustines, Blanc Cépage Vermentinu Cuvée Carco 2008.)

First course, "raw grilled langoustines": We were puzzled by that description, but sure enough, we each got a plate of sliced raw langoustine tails that had a delicious grilled-seafood flavor! They were accompanied by a little mound of savory rice pudding studded with crisp black and red crêpe strips. The results were absolutely delicious, but we were baffled. Finally, we asked our waitress, who revealed that the chef grilled a bunch of langoustines, then dressed the raw ones with the resulting grilled-langoustine oil. What a great idea! (With the langoustines, Blanc Cépage Vermentinu Cuvée Carco 2008.)

Second course: Pan-seared duck foie gras with peaches, accompanied by a balsamic vinegar syrup and cracked black pepper. The foie gras, although delicious, was a little firmer in texture than usual—it must be difficult to get the perfect texture while producing 100 portions simultaneously. Don't get me wrong—it was still outstanding! (With the munchies, Blanc Cépage Biancu Gentile 2007.)

Second course: Pan-seared duck foie gras with peaches, accompanied by a balsamic vinegar syrup and cracked black pepper. The foie gras, although delicious, was a little firmer in texture than usual—it must be difficult to get the perfect texture while producing 100 portions simultaneously. Don't get me wrong—it was still outstanding! (With the munchies, Blanc Cépage Biancu Gentile 2007.)

Third course: Grilled Charolais beef (locally grown) topped with chanterelle mushrooms and poached celery slices. Large dots of parsley puree and a loop of what I think was a purée of "boudin noir" (blood pudding). On the side, we each got a wine goblet full of amazingly insubstantial mashed-potato fluff topped with bacon bits and tiny diced chives. Yum! The beef was billed as "filet," but it was clearly not what we would call filet (i.e., the tenderloin). Neither did it have the great tenderness Americans prize in steaks, but it certainly wasn't tough, and it had great flavor! (With the beef and cheese, Magnum rouge Cépage Nielluccio Cuvée Carco 2006.)

Cheese course: A plate presenting two Corsican cheeses—a goat cheese thickly coated with herbs of the maquis (i.e., Corsican chapparal) and a dry sheep's-milk cheese, both delicious—accompanied by a slice of toasted hazelnut-and-fig bread, a spoonful of excellent fig jam, and a tiny dish full of nutmeats (mine also contained a very small insect, but I shooed him away).

Cheese course: A plate presenting two Corsican cheeses—a goat cheese thickly coated with herbs of the maquis (i.e., Corsican chapparal) and a dry sheep's-milk cheese, both delicious—accompanied by a slice of toasted hazelnut-and-fig bread, a spoonful of excellent fig jam, and a tiny dish full of nutmeats (mine also contained a very small insect, but I shooed him away).

At the right is our hostess, the chef's wife, chatting with the people at the wine-maker's table. (Note, in the foreground, our own personal one-candle crystal chandelier; each table had one.) She also visited our table, as did the winemaker. The chef was busy, but he came out to say goodby when we left.

The predessert was a little glass filled with raspberry coulis, rose-flavored cream, and raspberries.

The predessert was a little glass filled with raspberry coulis, rose-flavored cream, and raspberries.

The dessert was two apricot halves, each topped with a mixture of ground almonds, milk, and egg yolk; baked until crisp on top; sprinkled with powdered sugar; and served warm. In the center, a scoop of very vanilla ice cream, and to one side, a tiny warm almond cake. (With the dessert, a 2008 Muscat.)

We declined coffee, but they brought us mignardises while we waited for the bill. The red things are cherry "magic balls," the cakes are just little warm cakes, and the tiny pots are filled with crême-brulé mixture and topped with black-currant syrup (by far the best!). They forgot to bring us spoons small enough to reach into the pots, so we just reverved our dessert spoons and ate them with the handles.

We declined coffee, but they brought us mignardises while we waited for the bill. The red things are cherry "magic balls," the cakes are just little warm cakes, and the tiny pots are filled with crême-brulé mixture and topped with black-currant syrup (by far the best!). They forgot to bring us spoons small enough to reach into the pots, so we just reverved our dessert spoons and ate them with the handles.

After dinner, we walked back via the Place Carnot and were struck, as is often the case at night in France at this time of year, by a great wave of the scent of linden trees ("tilleuls," genus Tilia) in flower. The scent is less intense during the day, even though that's when the bees are busiest in the trees, but it comes out strongly at dusk.

Finally, here's David's shot of a terrific cement model of the medieval city of Beaune, near the Museum of Wine. Most of the walls are gone now, but many of the round towers and corner bastions are still there (housing wine companies, mostly) Our hotel is in the little street just inside the walls a couple of blocks to the right of the farthest corner; and this evening's restaurant it farther to the right, at the corner just inside the frame. The winery we have tickets to tour later in the week is at the left-most corner. The whole place is not very big.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Wednesday, we had afternoon reservations for a Safari Tour of the vinyards (alas, the Office de Tourisme no longer has the personnel to organize the great half-day bus excursions they used to do, so a private company has taken up the slack), so we set off to spend the morning in the city's Wine Museum, which is housed in the local palace (actually, more of an urban castle) of the Ducs de Bourgogne. On the way, we passed through this small produce market (taking place, appropriately enough, in the Place du Marché). As usual, the fruits and vegetables were much better looking than those available in Tallahassee. Another vegetable stand had leeks in two sizes—the usual large ones and tiny, baby ones. only a little bigger than scallions. Other stands sold hand-made soap, dried fruit, honey products, etc. No meat, fish, cheese, or hardware. That stuff would appear on Saturdays at the big, official weekly market.

Wednesday, we had afternoon reservations for a Safari Tour of the vinyards (alas, the Office de Tourisme no longer has the personnel to organize the great half-day bus excursions they used to do, so a private company has taken up the slack), so we set off to spend the morning in the city's Wine Museum, which is housed in the local palace (actually, more of an urban castle) of the Ducs de Bourgogne. On the way, we passed through this small produce market (taking place, appropriately enough, in the Place du Marché). As usual, the fruits and vegetables were much better looking than those available in Tallahassee. Another vegetable stand had leeks in two sizes—the usual large ones and tiny, baby ones. only a little bigger than scallions. Other stands sold hand-made soap, dried fruit, honey products, etc. No meat, fish, cheese, or hardware. That stuff would appear on Saturdays at the big, official weekly market.

From there, we turned up the Rue de Paradis (Paradise Street) to what was originally the back door of the Duc de Bourgogne's Beaune townhouse, which now houses the Wine Museum. Inside, we were greeted by the famous Notre Dame de Beaune (otherwise known as the Madonna of the Bunch of Grapes). Like all the museums we've visited, this one was extremely edifying—museumship (museumcraft?) has improved enormously since we were dragged as children through room after room of dusty stuff will little labels on it. It included extensive displays about wine-label art and the ways it has changed over the centuries; the lives of winemakers through history (including an ornate hurdy-gurdy, a chubby stringed instrument, like an extremely foreshortened lute or mandolin, with a crank on the side; it was apparently the common source of music at parties and celebrations); an early-20th-century photograph of three naked men jumping into a vat of already pressed wine to "turn the cap" (mix the floating mass of skins, seeds, and stems back into the liquid below, to encourage development of a good red color); and a great selection of wine-makers' proverbs: "Vigne grélée, vigne fumée" ("A vine hailed on is a smoked vine"—'fraid I don't understand that one; I've been looking for someone who can tell me what a "smoked vine" is); "S'il tonne en mars, le vigneron se lasse " ("If it thunders in March, the winemaker relaxes"; because everything will be okay, I guess?); "Si tu tailles en février, tu mets du raisin dans ton panier" ("If you prune in February, you put grapes in your basket"; that one's clearer); "La brise nourit la Bourgogne; le vent du Morvan l'affame" ("The breeze nourishes Burgundy; the wind from the Morvan, i.e., from the west, starves it"); "Pluie de février vaut du fumier" (another ambiguous one: "Rain in February is worth [um...] manure"; does that mean "is worthless" or "is as good as fertilizer"?); "La pluie de St. Médard diminue la vendange d'un quart" ("Rain on St. Médard's day [whenever that is] reduces the harvest by a quarter") ; "Tonnerre d'avril replit les barrils" ("Thunder in April fills the barrels"); "De St. Paul le temps clair et beau annonce plus de vin que d'eau" ("Fine weather at St. Paul's day [whenever that is] portends more wine than water").

From there, we turned up the Rue de Paradis (Paradise Street) to what was originally the back door of the Duc de Bourgogne's Beaune townhouse, which now houses the Wine Museum. Inside, we were greeted by the famous Notre Dame de Beaune (otherwise known as the Madonna of the Bunch of Grapes). Like all the museums we've visited, this one was extremely edifying—museumship (museumcraft?) has improved enormously since we were dragged as children through room after room of dusty stuff will little labels on it. It included extensive displays about wine-label art and the ways it has changed over the centuries; the lives of winemakers through history (including an ornate hurdy-gurdy, a chubby stringed instrument, like an extremely foreshortened lute or mandolin, with a crank on the side; it was apparently the common source of music at parties and celebrations); an early-20th-century photograph of three naked men jumping into a vat of already pressed wine to "turn the cap" (mix the floating mass of skins, seeds, and stems back into the liquid below, to encourage development of a good red color); and a great selection of wine-makers' proverbs: "Vigne grélée, vigne fumée" ("A vine hailed on is a smoked vine"—'fraid I don't understand that one; I've been looking for someone who can tell me what a "smoked vine" is); "S'il tonne en mars, le vigneron se lasse " ("If it thunders in March, the winemaker relaxes"; because everything will be okay, I guess?); "Si tu tailles en février, tu mets du raisin dans ton panier" ("If you prune in February, you put grapes in your basket"; that one's clearer); "La brise nourit la Bourgogne; le vent du Morvan l'affame" ("The breeze nourishes Burgundy; the wind from the Morvan, i.e., from the west, starves it"); "Pluie de février vaut du fumier" (another ambiguous one: "Rain in February is worth [um...] manure"; does that mean "is worthless" or "is as good as fertilizer"?); "La pluie de St. Médard diminue la vendange d'un quart" ("Rain on St. Médard's day [whenever that is] reduces the harvest by a quarter") ; "Tonnerre d'avril replit les barrils" ("Thunder in April fills the barrels"); "De St. Paul le temps clair et beau annonce plus de vin que d'eau" ("Fine weather at St. Paul's day [whenever that is] portends more wine than water").

The museum had particularly extensive (and sometimes rather technical) sections on the geology and meteorology of the Côte d'Or, including (among many others) these two models. The displays explain many differences between the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune, making clear that the boundary between them is not arbitrary—for example, the former is an anticline, the latter a syncline, and they face slightly different directions, therefore receiving slightly different sun exposure. Really interesting. [Dan: If you'd like more detail, I have many more photos of the displays and explanatory panels on the geology—sorry, not very volcanic.]

The museum had particularly extensive (and sometimes rather technical) sections on the geology and meteorology of the Côte d'Or, including (among many others) these two models. The displays explain many differences between the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune, making clear that the boundary between them is not arbitrary—for example, the former is an anticline, the latter a syncline, and they face slightly different directions, therefore receiving slightly different sun exposure. Really interesting. [Dan: If you'd like more detail, I have many more photos of the displays and explanatory panels on the geology—sorry, not very volcanic.]

Like most wine museums, this one includes an extensive section on barrel-making (apparently anybody can make a bottle—bottle shapes are sometimes discussed, but the manufacture is never mentioned, whereas barrel making remains a highly skilled craft, and even modern barrels cost thousands of dollars and must be replaced every three years or so). We watched an excellent video on the construction of barrels entirely by hand, then a briefer one on modern barrel making—it's still done mostly by hand, but, for example, the staves are moved (by hand) over a power planer rather than shaped with a hand-powered plane. The exhibit ended with this display of miniature barrels and wine presses constructed inside wine bottles (together with some of the tools used to construct them—the inland equivalent of ships in a bottle. At the right is a painting of a local tradition—tying a bunch of grapes onto the household's statue of the virgin Mary, in hopes of a successful harvest and vinification.

Like most wine museums, this one includes an extensive section on barrel-making (apparently anybody can make a bottle—bottle shapes are sometimes discussed, but the manufacture is never mentioned, whereas barrel making remains a highly skilled craft, and even modern barrels cost thousands of dollars and must be replaced every three years or so). We watched an excellent video on the construction of barrels entirely by hand, then a briefer one on modern barrel making—it's still done mostly by hand, but, for example, the staves are moved (by hand) over a power planer rather than shaped with a hand-powered plane. The exhibit ended with this display of miniature barrels and wine presses constructed inside wine bottles (together with some of the tools used to construct them—the inland equivalent of ships in a bottle. At the right is a painting of a local tradition—tying a bunch of grapes onto the household's statue of the virgin Mary, in hopes of a successful harvest and vinification. Just before the exit, we passed through this display of three modern tapestries—the photo shows an entire small one and about a third of a large one (the third was intermediate in size, an abstract in shades of red, gold, and brown).

Just before the exit, we passed through this display of three modern tapestries—the photo shows an entire small one and about a third of a large one (the third was intermediate in size, an abstract in shades of red, gold, and brown).  We left the museum through the original front gate of the ducal townhouse and continued on to have a look at the town's main church, the Basilique de Notre Dame, and its peaceful cloister. The complex is a daughter house of the Abbey at Cluny and dates from about 1120. In the choir is displayed a famous black madonna and tapestries protraying the life of the virgin, but that section was closed for lunch when we were there—you can walk around the rest of the church by yourself, but that section is always guarded, and a sign warns you not to rattle the gate, lest you set off the burglar alarm.

We left the museum through the original front gate of the ducal townhouse and continued on to have a look at the town's main church, the Basilique de Notre Dame, and its peaceful cloister. The complex is a daughter house of the Abbey at Cluny and dates from about 1120. In the choir is displayed a famous black madonna and tapestries protraying the life of the virgin, but that section was closed for lunch when we were there—you can walk around the rest of the church by yourself, but that section is always guarded, and a sign warns you not to rattle the gate, lest you set off the burglar alarm. Finally, on the way back toward the tourist office (where our wine tour would start), and in search of lunch, we passed by the "beffroi" (belfry; I'm not sure how it differs from a "clocher") of Philippe le Bon. The street next to it is so narrow you can't even see it from below, and from here in the Place Marey, the trees are in the way, so this is about the best view you can get.

Finally, on the way back toward the tourist office (where our wine tour would start), and in search of lunch, we passed by the "beffroi" (belfry; I'm not sure how it differs from a "clocher") of Philippe le Bon. The street next to it is so narrow you can't even see it from below, and from here in the Place Marey, the trees are in the way, so this is about the best view you can get.

He started by driving us south out of Beaune and through Pommard (a typical Burgundian village, he said—600 inhabitants, 42 wine companies), then stopping out in the vines. He explained that these green grapes are gigantic for the time of year. The area has had lots of rain, so most of the vines set too many clusters, and the grapes are getting big very fast. Soon someone will come around and cut off all but about eight clusters per vine, retaining the most promising ones and especially those low on the plant. The vines in Burgundy are pruned very severely and kept quite small in comparison with those of other regions. Note, in the right-hand photo the different patches of vines, some older, some younger, divided by narrow bare strips by by stone walls. All of these plots are probably owned by different people. Across the road, Loïc pointed out a patch six rows wide and perhaps 100 m long that had been recently replanted and explained that it belonged to a different owner than the plots on either side. No markings indicate changes of ownership, he explained, but everyone in the area knows just who owns which rows.

He started by driving us south out of Beaune and through Pommard (a typical Burgundian village, he said—600 inhabitants, 42 wine companies), then stopping out in the vines. He explained that these green grapes are gigantic for the time of year. The area has had lots of rain, so most of the vines set too many clusters, and the grapes are getting big very fast. Soon someone will come around and cut off all but about eight clusters per vine, retaining the most promising ones and especially those low on the plant. The vines in Burgundy are pruned very severely and kept quite small in comparison with those of other regions. Note, in the right-hand photo the different patches of vines, some older, some younger, divided by narrow bare strips by by stone walls. All of these plots are probably owned by different people. Across the road, Loïc pointed out a patch six rows wide and perhaps 100 m long that had been recently replanted and explained that it belonged to a different owner than the plots on either side. No markings indicate changes of ownership, he explained, but everyone in the area knows just who owns which rows.

After Pommard, Volnay, and Monthélie, we stopped in Meursault to view the Town Hall, which was featured in a famous comic film called La Grande Vandrouille (the name means "the great wandering-around" but it is rendered into English as Don't Look Now: We're Being Shot At; we saw a mural in Beaune depicting the making of the film, which also used locations there). Our tour continued through Bouze les Beaune and ended in Savigny-les-Beaune, where Loïc grew up. He took us to the Domaine Serrigny, owned and operated by two young women, Francine and Marie-Laure Serrigny (elementary-school classmates of his). They are the youngest of four daughters in a family without sons and have decided to carry on their father's business. They own 7 ha (ca. 15 acres) of vines, but as it typical of the area, their holdings are not contiguous. They own two plots in "premier cru" areas, from which they could, if they wished, combine the harvest and label the resulting wine "Savigny-les-Beaune premier cru," but the wines from the two have slightly different character, so they keep them separate and label them by their "neighborhoods" within the premier cru—"La Dominode" and "Les Peuillets." Other areas they own are also planted with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, or Aligoté, so in all they produce seven different wines, four reds (including the two premier crus), and three whites of different designations. In all, they produce about 35,000 bottles a year. I didn't ask whether they bottle the wines themselves, by hand, or whether they call in a mechanized bottling company (running a robotic bottling line is considered the work of specialists—it has to be kept perfectly oiled and adjusted—so many winemakers who would use one only, say, two days a year just call in the experts, who park their truck-mounted line in the courtyard and run a hose into the barrels in the cellar), but they hand-paste all 35,000 labels themselves.

After Pommard, Volnay, and Monthélie, we stopped in Meursault to view the Town Hall, which was featured in a famous comic film called La Grande Vandrouille (the name means "the great wandering-around" but it is rendered into English as Don't Look Now: We're Being Shot At; we saw a mural in Beaune depicting the making of the film, which also used locations there). Our tour continued through Bouze les Beaune and ended in Savigny-les-Beaune, where Loïc grew up. He took us to the Domaine Serrigny, owned and operated by two young women, Francine and Marie-Laure Serrigny (elementary-school classmates of his). They are the youngest of four daughters in a family without sons and have decided to carry on their father's business. They own 7 ha (ca. 15 acres) of vines, but as it typical of the area, their holdings are not contiguous. They own two plots in "premier cru" areas, from which they could, if they wished, combine the harvest and label the resulting wine "Savigny-les-Beaune premier cru," but the wines from the two have slightly different character, so they keep them separate and label them by their "neighborhoods" within the premier cru—"La Dominode" and "Les Peuillets." Other areas they own are also planted with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, or Aligoté, so in all they produce seven different wines, four reds (including the two premier crus), and three whites of different designations. In all, they produce about 35,000 bottles a year. I didn't ask whether they bottle the wines themselves, by hand, or whether they call in a mechanized bottling company (running a robotic bottling line is considered the work of specialists—it has to be kept perfectly oiled and adjusted—so many winemakers who would use one only, say, two days a year just call in the experts, who park their truck-mounted line in the courtyard and run a hose into the barrels in the cellar), but they hand-paste all 35,000 labels themselves. Apparently, they're doing okay on their 7 ha, so Loïc's father's holdings must have been smaller—the hard part is that they're doing the whole thing alone (pruning, trimming, wire lifting, spraying, inspection, crushing, cap-turning, vinifying, bottling, labeling, and sales, without hired help except for the harvest, and holdings that size really call for three or even four people. Even though the sign on their gate says "tasting and sales," no one was there when we were—they were out in the vines trimming and lifting wires, so we could only taste because Loïc has a key to the place. We had our tastes in the smallest of their three cellars, which holds about 10,000 bottles.

Apparently, they're doing okay on their 7 ha, so Loïc's father's holdings must have been smaller—the hard part is that they're doing the whole thing alone (pruning, trimming, wire lifting, spraying, inspection, crushing, cap-turning, vinifying, bottling, labeling, and sales, without hired help except for the harvest, and holdings that size really call for three or even four people. Even though the sign on their gate says "tasting and sales," no one was there when we were—they were out in the vines trimming and lifting wires, so we could only taste because Loïc has a key to the place. We had our tastes in the smallest of their three cellars, which holds about 10,000 bottles. Loïc reminisced about turning the cap in his father's fermentation vats. Apparently, Burgundy grapes haven't been initially crushed "by foot" since the discovery of the lever—the grapes are quite hard at harvest— but even today, the cap is often turned that way. After the grapes are crushed, and the mixture of juice, pulp, seeds, skins, and stem is then dumped into a vat for the initial fermentation, the solids float to the top and form a layer that gels pretty solidly—firm enough, if you've left even a modest amount of stem attached to the grapes, to walk on. That gelled cap must be turned over and broken up so that the color from the skins can leach properly into the juice. The easiest and most practical method, at least for small producers, is to remove the shoes, socks, and long trousers and to push and shove with the feet. The practice can be dangerous—turning the cap liberates great waves of carbon dioxide (one breath can severly damage the lungs and a couple can kill an adult)—so they never work alone, and before they begin, the winemakers set up a tall narrow set of shelves with a candle on each shelf, and someone stands by with a big fan. The candles warn of the amount of CO2 accumulating on the floor—successive candles go out as the level rises. The guy with the fan leaps to the rescue of anyone who loses his balance and falls into the pool of CO2 (or the vat).

Loïc reminisced about turning the cap in his father's fermentation vats. Apparently, Burgundy grapes haven't been initially crushed "by foot" since the discovery of the lever—the grapes are quite hard at harvest— but even today, the cap is often turned that way. After the grapes are crushed, and the mixture of juice, pulp, seeds, skins, and stem is then dumped into a vat for the initial fermentation, the solids float to the top and form a layer that gels pretty solidly—firm enough, if you've left even a modest amount of stem attached to the grapes, to walk on. That gelled cap must be turned over and broken up so that the color from the skins can leach properly into the juice. The easiest and most practical method, at least for small producers, is to remove the shoes, socks, and long trousers and to push and shove with the feet. The practice can be dangerous—turning the cap liberates great waves of carbon dioxide (one breath can severly damage the lungs and a couple can kill an adult)—so they never work alone, and before they begin, the winemakers set up a tall narrow set of shelves with a candle on each shelf, and someone stands by with a big fan. The candles warn of the amount of CO2 accumulating on the floor—successive candles go out as the level rises. The guy with the fan leaps to the rescue of anyone who loses his balance and falls into the pool of CO2 (or the vat).

Dinner was at Le Jardin des Remparts, and back in March, when I made the reservation, the management had explained that the evening we had chosen was already scheduled for a special dinner, which we were welcome to join, but the menu would be set, and the whole thing would feature the wines of Corsica. Okay, we were fine with that, so we signed up. When we arrived at the restaurant, which has a lovely fenced and walled garden in front, we found a full-scale garden party in progress (though the dress code was not necessarily that approved by the queen; if anything, we were a bit overdressed).

Dinner was at Le Jardin des Remparts, and back in March, when I made the reservation, the management had explained that the evening we had chosen was already scheduled for a special dinner, which we were welcome to join, but the menu would be set, and the whole thing would feature the wines of Corsica. Okay, we were fine with that, so we signed up. When we arrived at the restaurant, which has a lovely fenced and walled garden in front, we found a full-scale garden party in progress (though the dress code was not necessarily that approved by the queen; if anything, we were a bit overdressed).  We presented ourselves to one of the staff as the American tourists who had stumbled into the affair, and soon Madame the hostess and her husband the chef, who were mingling with the guests, came over to introduce themselves, welcome us, and suggest that we not be shy about making friends with the others, most of whom were regulars at the restaurant. The dinner was to be accompanied by the wines of Antoine Arena (that's him in the blue shirt under the left-most white umbrella above), a Corsican winemaker. We never got straight how he and the restaurant were connected.

We presented ourselves to one of the staff as the American tourists who had stumbled into the affair, and soon Madame the hostess and her husband the chef, who were mingling with the guests, came over to introduce themselves, welcome us, and suggest that we not be shy about making friends with the others, most of whom were regulars at the restaurant. The dinner was to be accompanied by the wines of Antoine Arena (that's him in the blue shirt under the left-most white umbrella above), a Corsican winemaker. We never got straight how he and the restaurant were connected.

First course, "raw grilled langoustines": We were puzzled by that description, but sure enough, we each got a plate of sliced raw langoustine tails that had a delicious grilled-seafood flavor! They were accompanied by a little mound of savory rice pudding studded with crisp black and red crêpe strips. The results were absolutely delicious, but we were baffled. Finally, we asked our waitress, who revealed that the chef grilled a bunch of langoustines, then dressed the raw ones with the resulting grilled-langoustine oil. What a great idea! (With the langoustines, Blanc Cépage Vermentinu Cuvée Carco 2008.)

First course, "raw grilled langoustines": We were puzzled by that description, but sure enough, we each got a plate of sliced raw langoustine tails that had a delicious grilled-seafood flavor! They were accompanied by a little mound of savory rice pudding studded with crisp black and red crêpe strips. The results were absolutely delicious, but we were baffled. Finally, we asked our waitress, who revealed that the chef grilled a bunch of langoustines, then dressed the raw ones with the resulting grilled-langoustine oil. What a great idea! (With the langoustines, Blanc Cépage Vermentinu Cuvée Carco 2008.)

Second course: Pan-seared duck foie gras with peaches, accompanied by a balsamic vinegar syrup and cracked black pepper. The foie gras, although delicious, was a little firmer in texture than usual—it must be difficult to get the perfect texture while producing 100 portions simultaneously. Don't get me wrong—it was still outstanding! (With the munchies, Blanc Cépage Biancu Gentile 2007.)

Second course: Pan-seared duck foie gras with peaches, accompanied by a balsamic vinegar syrup and cracked black pepper. The foie gras, although delicious, was a little firmer in texture than usual—it must be difficult to get the perfect texture while producing 100 portions simultaneously. Don't get me wrong—it was still outstanding! (With the munchies, Blanc Cépage Biancu Gentile 2007.)

Cheese course: A plate presenting two Corsican cheeses—a goat cheese thickly coated with herbs of the maquis (i.e., Corsican chapparal) and a dry sheep's-milk cheese, both delicious—accompanied by a slice of toasted hazelnut-and-fig bread, a spoonful of excellent fig jam, and a tiny dish full of nutmeats (mine also contained a very small insect, but I shooed him away).

Cheese course: A plate presenting two Corsican cheeses—a goat cheese thickly coated with herbs of the maquis (i.e., Corsican chapparal) and a dry sheep's-milk cheese, both delicious—accompanied by a slice of toasted hazelnut-and-fig bread, a spoonful of excellent fig jam, and a tiny dish full of nutmeats (mine also contained a very small insect, but I shooed him away).

The predessert was a little glass filled with raspberry coulis, rose-flavored cream, and raspberries.

The predessert was a little glass filled with raspberry coulis, rose-flavored cream, and raspberries. We declined coffee, but they brought us mignardises while we waited for the bill. The red things are cherry "magic balls," the cakes are just little warm cakes, and the tiny pots are filled with crême-brulé mixture and topped with black-currant syrup (by far the best!). They forgot to bring us spoons small enough to reach into the pots, so we just reverved our dessert spoons and ate them with the handles.

We declined coffee, but they brought us mignardises while we waited for the bill. The red things are cherry "magic balls," the cakes are just little warm cakes, and the tiny pots are filled with crême-brulé mixture and topped with black-currant syrup (by far the best!). They forgot to bring us spoons small enough to reach into the pots, so we just reverved our dessert spoons and ate them with the handles.