Thursday, 18 June 2009, The train and the trail

Written 2 July 2009

At this point, we had three tickets left in our little Passe Beaune wallet, so we set out to use them up. We had thought to visit the Bouchard Ainé winery first, but as we passed through the Place du Marché, there was the little white train, just loading up, so we decided to do that first. Little white train tours of French cities are a long-standing tradition. Three or four little open-sided cars are pulled by a miniature locomotive made up to look like an old steam engine, with the tall cab, smokestack, and cow catcher. Well, the times they are a-changin'. This one was billed as "Visiotrain 2000," and it has been remodeled to look more like the TGV! Fortunately, the technology has improved in other ways as well—part of the tradition has been trains that rattled so loudly and speakers that garbled so badly that you couldn't understand the narration, but both train construction and accoustics have improved, so we had no trouble this time.

At this point, we had three tickets left in our little Passe Beaune wallet, so we set out to use them up. We had thought to visit the Bouchard Ainé winery first, but as we passed through the Place du Marché, there was the little white train, just loading up, so we decided to do that first. Little white train tours of French cities are a long-standing tradition. Three or four little open-sided cars are pulled by a miniature locomotive made up to look like an old steam engine, with the tall cab, smokestack, and cow catcher. Well, the times they are a-changin'. This one was billed as "Visiotrain 2000," and it has been remodeled to look more like the TGV! Fortunately, the technology has improved in other ways as well—part of the tradition has been trains that rattled so loudly and speakers that garbled so badly that you couldn't understand the narration, but both train construction and accoustics have improved, so we had no trouble this time.

A busload of Germans had just signed on for the tour and filled most of the first three cars, so we were consigned to the last row of the last car, behind Sam the cocker spaniel and the three English people he had brought with him. A sign specified "no animals on the benches," so Sam rode the whole way on his mistress's lap and seemed to enjoy the experience.

Even though we'd been in Beaune for several days by this time, the train tour managed to show and tell us a number of things we didn't know. For example, Louis Chevrolet was born and raised on the rue Maufoux, before emigrating (in 1901) to the U.S. and starting that car company. Jean Marey, who lived and worked in Beaune and is commemorated by this statue in the Place Marey, is credited with the invention of the moving picture—he developed and experimented with a series of systems for either producing rapid-fire multiple exposures on a single piece of film or taking a very rapid series of photos on separate frames. The relief next to his statue reproduces his famous "decomposition" of the movements of a galloping horse. At the right is a shot of the mural depicting the filming of La Grande Vandrouille.

Even though we'd been in Beaune for several days by this time, the train tour managed to show and tell us a number of things we didn't know. For example, Louis Chevrolet was born and raised on the rue Maufoux, before emigrating (in 1901) to the U.S. and starting that car company. Jean Marey, who lived and worked in Beaune and is commemorated by this statue in the Place Marey, is credited with the invention of the moving picture—he developed and experimented with a series of systems for either producing rapid-fire multiple exposures on a single piece of film or taking a very rapid series of photos on separate frames. The relief next to his statue reproduces his famous "decomposition" of the movements of a galloping horse. At the right is a shot of the mural depicting the filming of La Grande Vandrouille.

The narration of the train ride also pointed out many out-of-the-way architectural details and reminded us that the 17th-century Hôtel de Ville used to be an Ursuline convent.

The narration of the train ride also pointed out many out-of-the-way architectural details and reminded us that the 17th-century Hôtel de Ville used to be an Ursuline convent.

At one point, the train even took us out through the old city walls into the countryside to see the vines and the "Montagne de Beaune" (a hill) before taking us back in through a park to see the source of the river that used to flows through the town and now flows under it.

Once the train dropped us back at the Place du Marché, we set off toward our winery tour, prospecting for lunch along the way and stopping to admire this assortment of solid-chocolate carpentry, plumbing, and auto-repair tools, offered in honor of father's day.

We found lunch in the Place Monge. David had the usual salad with lardons, croutons, and egg, but I decided to try a new local specialty, "oeufs en meurette"—eggs poached in a red wine sauce. Traditionally, the sauce is thickened with flour, but this one was made with cornstarch or some other "clear" starch, so the sauce was shiny and transparent. It was a rich mixture of red wine and meat juices (basically, leftover sauce from a boeuf bourgignon, the local red-wine pot roast dish), with a few mushrooms and slivers of onion and carrot. Two eggs were poached in that sauce, then ladeled over a bunch of large croutons and topped with chopped parsley (actually, the eggs in this version seemed a little pale to have been poached in the sauce—they may have been poached separately beforehand—but the dish was delicious nonetheless; that's another I'll have to try at home). The restaurant didn't have ice cream, so for dessert I had a hot crisp waffle with cherry jam.

We found lunch in the Place Monge. David had the usual salad with lardons, croutons, and egg, but I decided to try a new local specialty, "oeufs en meurette"—eggs poached in a red wine sauce. Traditionally, the sauce is thickened with flour, but this one was made with cornstarch or some other "clear" starch, so the sauce was shiny and transparent. It was a rich mixture of red wine and meat juices (basically, leftover sauce from a boeuf bourgignon, the local red-wine pot roast dish), with a few mushrooms and slivers of onion and carrot. Two eggs were poached in that sauce, then ladeled over a bunch of large croutons and topped with chopped parsley (actually, the eggs in this version seemed a little pale to have been poached in the sauce—they may have been poached separately beforehand—but the dish was delicious nonetheless; that's another I'll have to try at home). The restaurant didn't have ice cream, so for dessert I had a hot crisp waffle with cherry jam.

Despite dawdling over lunch, we arrived at Bouchard Ainé before it reopened for the afternoon, so we settled on a shaded park bench for a while to admire this monument to Beaune's World War I dead.

Despite dawdling over lunch, we arrived at Bouchard Ainé before it reopened for the afternoon, so we settled on a shaded park bench for a while to admire this monument to Beaune's World War I dead.

Once the winery reopened, we moved inside (it was getting very hot out there), signed up for the tour, were issued a wine glass each for the duration of the visit, but still had half an hour to look at the exhibits while the rest of the tour (mostly English speakers) assembled. The company is called Bouchard Ainé et Fils (Bouchard the Elder and Son) to distinguish it from Bouchard Père et Fils (Bouchard the Father and Son)—at some point a generation or two after the founding of the original Bouchard company, the oldest son (born in 1720) struck out on his own, and it was the company of his descendents that we were touring (now in something like the ninth generation). Finally, our guide appeared and led us across the courtyard and down into the cellars. To distinguish its tour from many others available in the area, this winery has devised the "Parcours des Cinq Sens"—the Trail of the Five Senses—which purports to engage all of your five sense in the wine-tasting experience, a good deal for those, like me, who don't actually like tasting wine. "Hearing" was a little weak—as you stroll down the cellar hallway between lecture stops, you get to listen to the sound effects of the vinyard (bird song, mostly)—but the rest was pretty good. In addition to their many other products, they make "crémant de Bourgogne," so I don't know why they don't include the sound of a popping cork and fizzing bubbles.

I found "smell" the most interesting. We were shown into a cellar room decorated with (between the stacks of wine bottles) extremely appetizing framed posters of food—the traditional dishes of the Burgundy region. On a series of tables around three sides of the room were corked spherical glass jars. The guide pulled out all the corks and invited us to sniff and try to identify the contents. Often you could identify them by sight without even sniffing, but the guide warned us that a few tricks were being played. Much sniffing and discussion ensued: Cinnamon, cloves, and orange were easy; everybody got those. Another jar, filled with crumbly black stuff, baffled everyone—it turned out to be lapsang soochong tea leaves, smelling of smoke. I was the only one to recognize the one in the center of the photo—cassis!—the artificial cherries were only there as a blind. A jar that baffled me but was recognized by several Brits was violet—it is a cruel trick of nature that North American violets are odorless.

I found "smell" the most interesting. We were shown into a cellar room decorated with (between the stacks of wine bottles) extremely appetizing framed posters of food—the traditional dishes of the Burgundy region. On a series of tables around three sides of the room were corked spherical glass jars. The guide pulled out all the corks and invited us to sniff and try to identify the contents. Often you could identify them by sight without even sniffing, but the guide warned us that a few tricks were being played. Much sniffing and discussion ensued: Cinnamon, cloves, and orange were easy; everybody got those. Another jar, filled with crumbly black stuff, baffled everyone—it turned out to be lapsang soochong tea leaves, smelling of smoke. I was the only one to recognize the one in the center of the photo—cassis!—the artificial cherries were only there as a blind. A jar that baffled me but was recognized by several Brits was violet—it is a cruel trick of nature that North American violets are odorless.

The photo at the right shows a cellar room full of barrels (of the standard Burgundian size known as a "pièce"). Chardonnay is often aged in them, so soak up the flavor of the wood. The barrels are individually hand made (every stave hand-shaped, though with assistance from some power tools) of French oak, each one costs some thousands of euros, and they must be replaced every three years or so, once the wood has given up most of its flavor. As the guide pointed out, not all wines are worth the expense, and some would not be improved by the process, so those are processed entirely in stainless steel and glass. The winery tries to recoup some of the cost by selling the used barrels as souvenirs, planters, etc., so if you're in the market (building a trans-Atlantic raft? planning a large container garden?), I'll send you the address. I didn't think to ask whether you could just sand down the interior to expose a new surface and get a couple more years out of them; I'm sure somebody's thought of it.

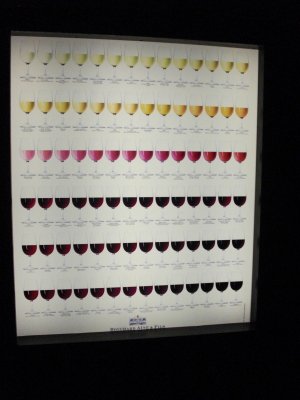

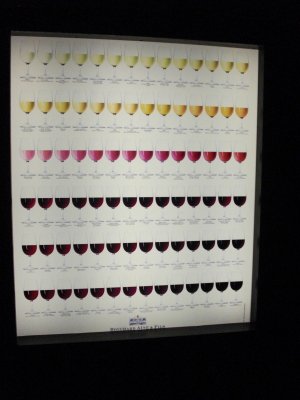

The "sight" stop made use of one of two absolutely brilliant posters the company has produced, a poor photo of which appears here. It presents, in order, 84 different wine colors, each named in French and in English. The names range from "acacia honey" to "squirrel" to "Grand Canyon" and on into the purples. The guide poured several wines, tilted the glasses, and held them against a light to illustrate what you can tell about the wine from the colors. For example, in red Burgundies, dark color and purple tinge at the edges indicates that wine is probably still too young; paler color and a slight tawny tinge indicate greater maturity. The poster must be a great help to people trying to compare wines, e.g., over the phone (even within the company,which has holdings in many different regions).

The "sight" stop made use of one of two absolutely brilliant posters the company has produced, a poor photo of which appears here. It presents, in order, 84 different wine colors, each named in French and in English. The names range from "acacia honey" to "squirrel" to "Grand Canyon" and on into the purples. The guide poured several wines, tilted the glasses, and held them against a light to illustrate what you can tell about the wine from the colors. For example, in red Burgundies, dark color and purple tinge at the edges indicates that wine is probably still too young; paler color and a slight tawny tinge indicate greater maturity. The poster must be a great help to people trying to compare wines, e.g., over the phone (even within the company,which has holdings in many different regions).

The guide was rather apologetic about the "touch" stop, but I thought it was a really good idea. A long metal bar, stretching across the room from wall to wall, was upholstered, at intervals of about 18 inches, with about a dozen different fabrics—raw silk, refined silk, satin, leather, vinyl, fuzzy burlap, canvas, thin velvet, thick velvet—over which we were encouraged to run our fingers. They were chosen to simulate, to the touch of the hand, the mouthfeels of wines of different tannin and other chemical contents. Again, what a great training aid for teaching the vocabulary of wine tasting!

Finally, back in the initial display area, although illustrative tastes had been offered along the way at the various stops, we came to the serious "taste" portion, where everyone got to taste and compare several of the company's locally produced wines. The guide presented the other of the company's brilliant posters, this one showing 84 wine glasses, each containing something illustrating a flavor one might look for in a wine—chocolate, leather, butter, fern, cherries, red currants, black currants, bell pepper, new-mown hay, honey, hazelnut, toast, acorns, juniper, banana, etc., etc. Not so important as a teaching aid, but decorative as all get out! The posters were for sale, at 10 euros each, but I resisted—they are such a pain to travel with, especially if packed to resist crushing—but I'm considering mailing ordering a set, though I shudder to think what the shipping will cost. You can see them (with cool mouse-over magnifier feature, though the resolution isn't quite good enough to make the labels legible) and order them at http://www.bouchard-aine.fr/fr/boutique/.

All along the way, I had steadfastly refused all offers to taste (why ruin a good tour?), but when the guide ended the visit by offering a taste of a special "ratafia de cassis," a rarely available liqueur of black currants at just 5% alcohol, I was first in line holding my glass out. He laughed—"Ah! The one interested in cuisine!" Apparently he had noticed that, while everyone else was comparing the tastes of wine to the odors in the sniffing jars, I was intently studying the food posters. Anyway, that ratafia, its alcohol content barely noticeable, was absolutely delicious!

At this point, a single ticket remained in our Passe Beaune wallet: the Musée des Beaux Arts, whose narrow and idiosyncratic opening hours had thwarted two previous attempted visits. I wanted to see it, and this was the last opening in our Beaune schedule, but David's feet hurt, and he wanted to sit at a sidewalk café, sip, and people-watch. So we parted ways in the Place Carnot—he settled at a café table for a citron pressé (having wine-tasted his quota for the afternoon), and I set off for the museum, agreeing to check back in less than 90 minutes. If he wasn't there, he'd be back at the room.

Outside the building housing th museum (and the Office de Tourisme, some of the city's administrative offices, and several other organizations) was this glass-recycling station. We thought the cylindrical containers rather small for the purpose until we discovered that each one is actually a chute leading to a large-dumpster-sized subterranean bin (much less obtrusive than the above-ground six-foot cubes that encumber Paris's sidewalks). I have no idea how they're emptied (through a chute into the building's subbasement? by a truck that lifts them out of the ground?)

Outside the building housing th museum (and the Office de Tourisme, some of the city's administrative offices, and several other organizations) was this glass-recycling station. We thought the cylindrical containers rather small for the purpose until we discovered that each one is actually a chute leading to a large-dumpster-sized subterranean bin (much less obtrusive than the above-ground six-foot cubes that encumber Paris's sidewalks). I have no idea how they're emptied (through a chute into the building's subbasement? by a truck that lifts them out of the ground?)

The museum is small but contains a little bit of all the obligatory categories: for example, one case each of locally excavated prehistorical potsherds and charred bones and seeds, Celtic belt buckles, and Roman inscriptions. In the reception room, where you buy tickets, is this scale model (perhaps six feet long) of the Basilique de Notre Dame, woven entirely of straw.

The model was interesting, but being short of time, I by-passed the archeological stuff and went on to look for things more to my taste. The museum had only one still life, a large-format painting of dead game birds, centered on a turkey—not quite naturalistic enough, I thought. It featured multiple works by each of several favorite sons of Beaune, in particular Hippolyte Michaud (1823-1886), who produced large, realistic, romantic paintings of allegorical (the dying artist surrounded by real and mythological mourners) scenes and a couple of very nice self-portraits.

The model was interesting, but being short of time, I by-passed the archeological stuff and went on to look for things more to my taste. The museum had only one still life, a large-format painting of dead game birds, centered on a turkey—not quite naturalistic enough, I thought. It featured multiple works by each of several favorite sons of Beaune, in particular Hippolyte Michaud (1823-1886), who produced large, realistic, romantic paintings of allegorical (the dying artist surrounded by real and mythological mourners) scenes and a couple of very nice self-portraits.

I especially like this portrait by Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse (1784-1844) of his aunt and this more or less life-size bust of Lot's wife, by Pierre Roche (1855-1922) made, strangely, of lead.

Another favorite son, whose name I didn't record, produced land- and sea-scapes of Venice, rather like Cannaletto. Near the exit was a group of multiple photos by Jean Marey, the motion-picture guy, including the usual galloping-horse series, a great pole-vaulting series, and an adorable multiple exposure of a toddler leaving his father's hands to walk a few unsteady steps to his waiting mother's arms.

My favorite piece, though, was this one, entitled "The Living Cross," which at first I thought must be 20th century, but it turns out to be 400 years older! It's thought to be 16th century, attributed only to "École Crétroise?" It's protected behind a sheet of plexiglas, so I'm afraid I couldn't get all the glare off it for the photo. It is described as affirming the advent of a new law with the death of Christ. Each of the four arms of the cross terminates in a real arm. The top one brandishes the key to the heavenly Jerusalem, depicted across the top, while the bottom one uses a pickaxe to do something to or for the dead (a devil at the lower right is tethered to the foot of the cross by a chain). The left arm wields a sword to slice off the arm of the blindfolded woman on the donkey, who carries a flag depicting a scorpion and represents The Synagogue. The twigs sprouting from that arm are withering and dying. Meanwhile, the right arm crowns The Church, while the wound in Christ's side spurts blood into the cup she holds. Its twigs are green and flourishing. The various apostles stand around doing apostle-like things. Amazing.

My favorite piece, though, was this one, entitled "The Living Cross," which at first I thought must be 20th century, but it turns out to be 400 years older! It's thought to be 16th century, attributed only to "École Crétroise?" It's protected behind a sheet of plexiglas, so I'm afraid I couldn't get all the glare off it for the photo. It is described as affirming the advent of a new law with the death of Christ. Each of the four arms of the cross terminates in a real arm. The top one brandishes the key to the heavenly Jerusalem, depicted across the top, while the bottom one uses a pickaxe to do something to or for the dead (a devil at the lower right is tethered to the foot of the cross by a chain). The left arm wields a sword to slice off the arm of the blindfolded woman on the donkey, who carries a flag depicting a scorpion and represents The Synagogue. The twigs sprouting from that arm are withering and dying. Meanwhile, the right arm crowns The Church, while the wound in Christ's side spurts blood into the cup she holds. Its twigs are green and flourishing. The various apostles stand around doing apostle-like things. Amazing.

When I got back to the Place Carnot, David was gone, so I headed back to the hotel, where I got this nice shot of the smaller internior courtyard, the one roofed with glass, from the second-floor walkway on the way to our room.

When I got back to the Place Carnot, David was gone, so I headed back to the hotel, where I got this nice shot of the smaller internior courtyard, the one roofed with glass, from the second-floor walkway on the way to our room.

Our restaurant for the evening, l'Hostellerie de Levernois (GM 15/20), was located at a golf resort several kilometers out of town, so we took the car. I confess that my experience of golf-course restaurants, even in France, led me to expect something a little less grand, even for a highly ranked establishment. But grand it was. We took our apperitifs on the terrace; the photo below shows our waiter preparing them at what passes for a tiki bar in places like this.

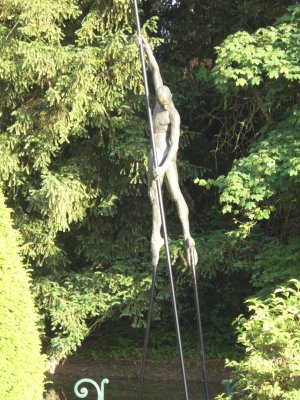

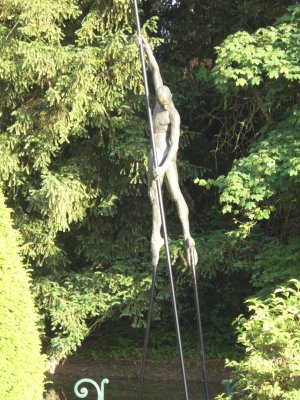

Small, beautifully landscaped bodies of water were visible on three sides, each with at least one sculpture standing in it on stilts. My favorite is this guy wielding what I take to be a harpoon (or maybe a punting pole). Our least favorite, posed on the lawn, was a bright candy-apple red plastic abstract/portly dancing female nude (depending on how you looked at it) one copy of which we had been walking by (and making fun of) all week outside the artist's gallery in Beaune.

Small, beautifully landscaped bodies of water were visible on three sides, each with at least one sculpture standing in it on stilts. My favorite is this guy wielding what I take to be a harpoon (or maybe a punting pole). Our least favorite, posed on the lawn, was a bright candy-apple red plastic abstract/portly dancing female nude (depending on how you looked at it) one copy of which we had been walking by (and making fun of) all week outside the artist's gallery in Beaune.

We studied the menu while we sipped our drinks, listened to the birds, and nibbled the first amuse-bouche (variously flavored bread sticks, puff-pastry straws with anchovy bits, and little semicircles of smoked salmon draped over herbed cream). The prices took us aback—try (do the math) twice the price we'd been paying for dinners in Beaune this week—but it's what we come to France for, so we pushed our eyeballs back into their sockets and ordered the all-lobster menu—why not? It wasn't even the most expensive.

We studied the menu while we sipped our drinks, listened to the birds, and nibbled the first amuse-bouche (variously flavored bread sticks, puff-pastry straws with anchovy bits, and little semicircles of smoked salmon draped over herbed cream). The prices took us aback—try (do the math) twice the price we'd been paying for dinners in Beaune this week—but it's what we come to France for, so we pushed our eyeballs back into their sockets and ordered the all-lobster menu—why not? It wasn't even the most expensive.

Once we'd finished our drinks and made our menu choices, we were shown to a table inside and served the "official amuse-bouche (as opposed to the munchies automatically served with any apperitif), on a slab of slate, of course—a bright-pink coarse purée of beetroot and "coumbasse" (or "gombasse"?), a term I haven't been able to find in any of my dictionaries or even on the internet—anybody have a clue? It was topped with bite-sized chunks of cooked shrimp and dill and was delicious. No, I'm not drinking cranberry juice with it; that's just the color of the water glasses.

Once we'd finished our drinks and made our menu choices, we were shown to a table inside and served the "official amuse-bouche (as opposed to the munchies automatically served with any apperitif), on a slab of slate, of course—a bright-pink coarse purée of beetroot and "coumbasse" (or "gombasse"?), a term I haven't been able to find in any of my dictionaries or even on the internet—anybody have a clue? It was topped with bite-sized chunks of cooked shrimp and dill and was delicious. No, I'm not drinking cranberry juice with it; that's just the color of the water glasses.

Each of us was then served an entire small lobster, divided up into three separate courses (they didn't find a way to include lobster in the cheese or desserts. We were delighted to be served both "normal" and algae butter; the minute I saw the latter, I knew (before the waiter confirmed it) that we were getting Bordier butter and that the "normal" would be that great, salty Breton stuff we love.

First course: The lobster's right claw, wrapped in a feuille de brik and fried crisp, served on top of an equally crisp fried squash blossom (and its attached tiny zucchini) with "Genoa-style" pesto, fried parsley, a bit of stewed tomato, and an oil and vinegar herb sauce. Yummy.

First course: The lobster's right claw, wrapped in a feuille de brik and fried crisp, served on top of an equally crisp fried squash blossom (and its attached tiny zucchini) with "Genoa-style" pesto, fried parsley, a bit of stewed tomato, and an oil and vinegar herb sauce. Yummy.

Second course: The lobster's left claw and meat from the body, enclosed in one large ravioli, served in a lobster bisque flavored with the lobster coral and topped with a bit of tomato and large Parmesan flates. Excellent!

Third course: The lobster's tail, simmered in a covered casserole, then served over a bulgur pilaf flavored with curry spices and studded with currants, apricots, and almonds. The lobster was very good, but the bulgur was outstanding!

Third course: The lobster's tail, simmered in a covered casserole, then served over a bulgur pilaf flavored with curry spices and studded with currants, apricots, and almonds. The lobster was very good, but the bulgur was outstanding!

The cheese service was even more of a production that usual, because the restaurant does not use a trolly. First, two small service tables must be moved to your tableside. Then your server fetches the smaller of the cheese trays (the one arrayed with all the smaller goat cheeses) to place on one of them. They he has to recruit help to bring the other tray (shown here), which is too large to be moved by one person, to place on the other. The system has the advantage that the cheeses are not whisked away (back to the cheese hangar or wherever) as soon as you make your choices—you get to study them until some other table needs them. David chose Beaufort, Cîteaux, and the two bleus (fourme d'Ambert and Roquefort). I had Charolais (made, despite the name, with goat's milk), Puligny-St.-Pierre, Cîteaux, and Époisse.

Dessert came in three parts: a white chocolate concoction decorated with dark chocolate "sails," a cold soup of fresh cherries with vanilla ice cream, and a miniature cherry milkshake (with, on the side, a whole fresh cherry encased in a clear sugar shell), plus mignardises, of course.

Dessert came in three parts: a white chocolate concoction decorated with dark chocolate "sails," a cold soup of fresh cherries with vanilla ice cream, and a miniature cherry milkshake (with, on the side, a whole fresh cherry encased in a clear sugar shell), plus mignardises, of course.

Finally, here are photos we happened to get of the gate of Le Jardin des Remparts, where we had the Corsican wine dinner, and, just around the corner from it, an old "lavoir" (communal wash house, where housewives brought their own laundry and any they did for hire). The latter is a lovely and picturesque setting, especially now with the hanging baskets and lily pads, but if siting a washhouse, I personnally would have placedit upstream rather than downstream from the outfall of the Hospices.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

At this point, we had three tickets left in our little Passe Beaune wallet, so we set out to use them up. We had thought to visit the Bouchard Ainé winery first, but as we passed through the Place du Marché, there was the little white train, just loading up, so we decided to do that first. Little white train tours of French cities are a long-standing tradition. Three or four little open-sided cars are pulled by a miniature locomotive made up to look like an old steam engine, with the tall cab, smokestack, and cow catcher. Well, the times they are a-changin'. This one was billed as "Visiotrain 2000," and it has been remodeled to look more like the TGV! Fortunately, the technology has improved in other ways as well—part of the tradition has been trains that rattled so loudly and speakers that garbled so badly that you couldn't understand the narration, but both train construction and accoustics have improved, so we had no trouble this time.

At this point, we had three tickets left in our little Passe Beaune wallet, so we set out to use them up. We had thought to visit the Bouchard Ainé winery first, but as we passed through the Place du Marché, there was the little white train, just loading up, so we decided to do that first. Little white train tours of French cities are a long-standing tradition. Three or four little open-sided cars are pulled by a miniature locomotive made up to look like an old steam engine, with the tall cab, smokestack, and cow catcher. Well, the times they are a-changin'. This one was billed as "Visiotrain 2000," and it has been remodeled to look more like the TGV! Fortunately, the technology has improved in other ways as well—part of the tradition has been trains that rattled so loudly and speakers that garbled so badly that you couldn't understand the narration, but both train construction and accoustics have improved, so we had no trouble this time.

Even though we'd been in Beaune for several days by this time, the train tour managed to show and tell us a number of things we didn't know. For example, Louis Chevrolet was born and raised on the rue Maufoux, before emigrating (in 1901) to the U.S. and starting that car company. Jean Marey, who lived and worked in Beaune and is commemorated by this statue in the Place Marey, is credited with the invention of the moving picture—he developed and experimented with a series of systems for either producing rapid-fire multiple exposures on a single piece of film or taking a very rapid series of photos on separate frames. The relief next to his statue reproduces his famous "decomposition" of the movements of a galloping horse. At the right is a shot of the mural depicting the filming of La Grande Vandrouille.

Even though we'd been in Beaune for several days by this time, the train tour managed to show and tell us a number of things we didn't know. For example, Louis Chevrolet was born and raised on the rue Maufoux, before emigrating (in 1901) to the U.S. and starting that car company. Jean Marey, who lived and worked in Beaune and is commemorated by this statue in the Place Marey, is credited with the invention of the moving picture—he developed and experimented with a series of systems for either producing rapid-fire multiple exposures on a single piece of film or taking a very rapid series of photos on separate frames. The relief next to his statue reproduces his famous "decomposition" of the movements of a galloping horse. At the right is a shot of the mural depicting the filming of La Grande Vandrouille.

The narration of the train ride also pointed out many out-of-the-way architectural details and reminded us that the 17th-century Hôtel de Ville used to be an Ursuline convent.

The narration of the train ride also pointed out many out-of-the-way architectural details and reminded us that the 17th-century Hôtel de Ville used to be an Ursuline convent.

We found lunch in the Place Monge. David had the usual salad with lardons, croutons, and egg, but I decided to try a new local specialty, "oeufs en meurette"—eggs poached in a red wine sauce. Traditionally, the sauce is thickened with flour, but this one was made with cornstarch or some other "clear" starch, so the sauce was shiny and transparent. It was a rich mixture of red wine and meat juices (basically, leftover sauce from a boeuf bourgignon, the local red-wine pot roast dish), with a few mushrooms and slivers of onion and carrot. Two eggs were poached in that sauce, then ladeled over a bunch of large croutons and topped with chopped parsley (actually, the eggs in this version seemed a little pale to have been poached in the sauce—they may have been poached separately beforehand—but the dish was delicious nonetheless; that's another I'll have to try at home). The restaurant didn't have ice cream, so for dessert I had a hot crisp waffle with cherry jam.

We found lunch in the Place Monge. David had the usual salad with lardons, croutons, and egg, but I decided to try a new local specialty, "oeufs en meurette"—eggs poached in a red wine sauce. Traditionally, the sauce is thickened with flour, but this one was made with cornstarch or some other "clear" starch, so the sauce was shiny and transparent. It was a rich mixture of red wine and meat juices (basically, leftover sauce from a boeuf bourgignon, the local red-wine pot roast dish), with a few mushrooms and slivers of onion and carrot. Two eggs were poached in that sauce, then ladeled over a bunch of large croutons and topped with chopped parsley (actually, the eggs in this version seemed a little pale to have been poached in the sauce—they may have been poached separately beforehand—but the dish was delicious nonetheless; that's another I'll have to try at home). The restaurant didn't have ice cream, so for dessert I had a hot crisp waffle with cherry jam.

Despite dawdling over lunch, we arrived at Bouchard Ainé before it reopened for the afternoon, so we settled on a shaded park bench for a while to admire this monument to Beaune's World War I dead.

Despite dawdling over lunch, we arrived at Bouchard Ainé before it reopened for the afternoon, so we settled on a shaded park bench for a while to admire this monument to Beaune's World War I dead.

I found "smell" the most interesting. We were shown into a cellar room decorated with (between the stacks of wine bottles) extremely appetizing framed posters of food—the traditional dishes of the Burgundy region. On a series of tables around three sides of the room were corked spherical glass jars. The guide pulled out all the corks and invited us to sniff and try to identify the contents. Often you could identify them by sight without even sniffing, but the guide warned us that a few tricks were being played. Much sniffing and discussion ensued: Cinnamon, cloves, and orange were easy; everybody got those. Another jar, filled with crumbly black stuff, baffled everyone—it turned out to be lapsang soochong tea leaves, smelling of smoke. I was the only one to recognize the one in the center of the photo—cassis!—the artificial cherries were only there as a blind. A jar that baffled me but was recognized by several Brits was violet—it is a cruel trick of nature that North American violets are odorless.

I found "smell" the most interesting. We were shown into a cellar room decorated with (between the stacks of wine bottles) extremely appetizing framed posters of food—the traditional dishes of the Burgundy region. On a series of tables around three sides of the room were corked spherical glass jars. The guide pulled out all the corks and invited us to sniff and try to identify the contents. Often you could identify them by sight without even sniffing, but the guide warned us that a few tricks were being played. Much sniffing and discussion ensued: Cinnamon, cloves, and orange were easy; everybody got those. Another jar, filled with crumbly black stuff, baffled everyone—it turned out to be lapsang soochong tea leaves, smelling of smoke. I was the only one to recognize the one in the center of the photo—cassis!—the artificial cherries were only there as a blind. A jar that baffled me but was recognized by several Brits was violet—it is a cruel trick of nature that North American violets are odorless. The "sight" stop made use of one of two absolutely brilliant posters the company has produced, a poor photo of which appears here. It presents, in order, 84 different wine colors, each named in French and in English. The names range from "acacia honey" to "squirrel" to "Grand Canyon" and on into the purples. The guide poured several wines, tilted the glasses, and held them against a light to illustrate what you can tell about the wine from the colors. For example, in red Burgundies, dark color and purple tinge at the edges indicates that wine is probably still too young; paler color and a slight tawny tinge indicate greater maturity. The poster must be a great help to people trying to compare wines, e.g., over the phone (even within the company,which has holdings in many different regions).

The "sight" stop made use of one of two absolutely brilliant posters the company has produced, a poor photo of which appears here. It presents, in order, 84 different wine colors, each named in French and in English. The names range from "acacia honey" to "squirrel" to "Grand Canyon" and on into the purples. The guide poured several wines, tilted the glasses, and held them against a light to illustrate what you can tell about the wine from the colors. For example, in red Burgundies, dark color and purple tinge at the edges indicates that wine is probably still too young; paler color and a slight tawny tinge indicate greater maturity. The poster must be a great help to people trying to compare wines, e.g., over the phone (even within the company,which has holdings in many different regions).

Outside the building housing th museum (and the Office de Tourisme, some of the city's administrative offices, and several other organizations) was this glass-recycling station. We thought the cylindrical containers rather small for the purpose until we discovered that each one is actually a chute leading to a large-dumpster-sized subterranean bin (much less obtrusive than the above-ground six-foot cubes that encumber Paris's sidewalks). I have no idea how they're emptied (through a chute into the building's subbasement? by a truck that lifts them out of the ground?)

Outside the building housing th museum (and the Office de Tourisme, some of the city's administrative offices, and several other organizations) was this glass-recycling station. We thought the cylindrical containers rather small for the purpose until we discovered that each one is actually a chute leading to a large-dumpster-sized subterranean bin (much less obtrusive than the above-ground six-foot cubes that encumber Paris's sidewalks). I have no idea how they're emptied (through a chute into the building's subbasement? by a truck that lifts them out of the ground?)

The model was interesting, but being short of time, I by-passed the archeological stuff and went on to look for things more to my taste. The museum had only one still life, a large-format painting of dead game birds, centered on a turkey—not quite naturalistic enough, I thought. It featured multiple works by each of several favorite sons of Beaune, in particular Hippolyte Michaud (1823-1886), who produced large, realistic, romantic paintings of allegorical (the dying artist surrounded by real and mythological mourners) scenes and a couple of very nice self-portraits.

The model was interesting, but being short of time, I by-passed the archeological stuff and went on to look for things more to my taste. The museum had only one still life, a large-format painting of dead game birds, centered on a turkey—not quite naturalistic enough, I thought. It featured multiple works by each of several favorite sons of Beaune, in particular Hippolyte Michaud (1823-1886), who produced large, realistic, romantic paintings of allegorical (the dying artist surrounded by real and mythological mourners) scenes and a couple of very nice self-portraits. My favorite piece, though, was this one, entitled "The Living Cross," which at first I thought must be 20th century, but it turns out to be 400 years older! It's thought to be 16th century, attributed only to "École Crétroise?" It's protected behind a sheet of plexiglas, so I'm afraid I couldn't get all the glare off it for the photo. It is described as affirming the advent of a new law with the death of Christ. Each of the four arms of the cross terminates in a real arm. The top one brandishes the key to the heavenly Jerusalem, depicted across the top, while the bottom one uses a pickaxe to do something to or for the dead (a devil at the lower right is tethered to the foot of the cross by a chain). The left arm wields a sword to slice off the arm of the blindfolded woman on the donkey, who carries a flag depicting a scorpion and represents The Synagogue. The twigs sprouting from that arm are withering and dying. Meanwhile, the right arm crowns The Church, while the wound in Christ's side spurts blood into the cup she holds. Its twigs are green and flourishing. The various apostles stand around doing apostle-like things. Amazing.

My favorite piece, though, was this one, entitled "The Living Cross," which at first I thought must be 20th century, but it turns out to be 400 years older! It's thought to be 16th century, attributed only to "École Crétroise?" It's protected behind a sheet of plexiglas, so I'm afraid I couldn't get all the glare off it for the photo. It is described as affirming the advent of a new law with the death of Christ. Each of the four arms of the cross terminates in a real arm. The top one brandishes the key to the heavenly Jerusalem, depicted across the top, while the bottom one uses a pickaxe to do something to or for the dead (a devil at the lower right is tethered to the foot of the cross by a chain). The left arm wields a sword to slice off the arm of the blindfolded woman on the donkey, who carries a flag depicting a scorpion and represents The Synagogue. The twigs sprouting from that arm are withering and dying. Meanwhile, the right arm crowns The Church, while the wound in Christ's side spurts blood into the cup she holds. Its twigs are green and flourishing. The various apostles stand around doing apostle-like things. Amazing. When I got back to the Place Carnot, David was gone, so I headed back to the hotel, where I got this nice shot of the smaller internior courtyard, the one roofed with glass, from the second-floor walkway on the way to our room.

When I got back to the Place Carnot, David was gone, so I headed back to the hotel, where I got this nice shot of the smaller internior courtyard, the one roofed with glass, from the second-floor walkway on the way to our room.

Small, beautifully landscaped bodies of water were visible on three sides, each with at least one sculpture standing in it on stilts. My favorite is this guy wielding what I take to be a harpoon (or maybe a punting pole). Our least favorite, posed on the lawn, was a bright candy-apple red plastic abstract/portly dancing female nude (depending on how you looked at it) one copy of which we had been walking by (and making fun of) all week outside the artist's gallery in Beaune.

Small, beautifully landscaped bodies of water were visible on three sides, each with at least one sculpture standing in it on stilts. My favorite is this guy wielding what I take to be a harpoon (or maybe a punting pole). Our least favorite, posed on the lawn, was a bright candy-apple red plastic abstract/portly dancing female nude (depending on how you looked at it) one copy of which we had been walking by (and making fun of) all week outside the artist's gallery in Beaune. We studied the menu while we sipped our drinks, listened to the birds, and nibbled the first amuse-bouche (variously flavored bread sticks, puff-pastry straws with anchovy bits, and little semicircles of smoked salmon draped over herbed cream). The prices took us aback—try (do the math) twice the price we'd been paying for dinners in Beaune this week—but it's what we come to France for, so we pushed our eyeballs back into their sockets and ordered the all-lobster menu—why not? It wasn't even the most expensive.

We studied the menu while we sipped our drinks, listened to the birds, and nibbled the first amuse-bouche (variously flavored bread sticks, puff-pastry straws with anchovy bits, and little semicircles of smoked salmon draped over herbed cream). The prices took us aback—try (do the math) twice the price we'd been paying for dinners in Beaune this week—but it's what we come to France for, so we pushed our eyeballs back into their sockets and ordered the all-lobster menu—why not? It wasn't even the most expensive. Once we'd finished our drinks and made our menu choices, we were shown to a table inside and served the "official amuse-bouche (as opposed to the munchies automatically served with any apperitif), on a slab of slate, of course—a bright-pink coarse purée of beetroot and "coumbasse" (or "gombasse"?), a term I haven't been able to find in any of my dictionaries or even on the internet—anybody have a clue? It was topped with bite-sized chunks of cooked shrimp and dill and was delicious. No, I'm not drinking cranberry juice with it; that's just the color of the water glasses.

Once we'd finished our drinks and made our menu choices, we were shown to a table inside and served the "official amuse-bouche (as opposed to the munchies automatically served with any apperitif), on a slab of slate, of course—a bright-pink coarse purée of beetroot and "coumbasse" (or "gombasse"?), a term I haven't been able to find in any of my dictionaries or even on the internet—anybody have a clue? It was topped with bite-sized chunks of cooked shrimp and dill and was delicious. No, I'm not drinking cranberry juice with it; that's just the color of the water glasses.

First course: The lobster's right claw, wrapped in a feuille de brik and fried crisp, served on top of an equally crisp fried squash blossom (and its attached tiny zucchini) with "Genoa-style" pesto, fried parsley, a bit of stewed tomato, and an oil and vinegar herb sauce. Yummy.

First course: The lobster's right claw, wrapped in a feuille de brik and fried crisp, served on top of an equally crisp fried squash blossom (and its attached tiny zucchini) with "Genoa-style" pesto, fried parsley, a bit of stewed tomato, and an oil and vinegar herb sauce. Yummy.

Third course: The lobster's tail, simmered in a covered casserole, then served over a bulgur pilaf flavored with curry spices and studded with currants, apricots, and almonds. The lobster was very good, but the bulgur was outstanding!

Third course: The lobster's tail, simmered in a covered casserole, then served over a bulgur pilaf flavored with curry spices and studded with currants, apricots, and almonds. The lobster was very good, but the bulgur was outstanding!

Dessert came in three parts: a white chocolate concoction decorated with dark chocolate "sails," a cold soup of fresh cherries with vanilla ice cream, and a miniature cherry milkshake (with, on the side, a whole fresh cherry encased in a clear sugar shell), plus mignardises, of course.

Dessert came in three parts: a white chocolate concoction decorated with dark chocolate "sails," a cold soup of fresh cherries with vanilla ice cream, and a miniature cherry milkshake (with, on the side, a whole fresh cherry encased in a clear sugar shell), plus mignardises, of course.