Saturday, 20 June 2009, Beaune to Saulieu

Written 2 July 2009

Our departure from Hôtel des Remparts came with apologies. Two nights before, as we left the hotel to walk to our restaurant, Madame the proprietress had come hurrying after us. She was shocked to have learned that, although we had been there several nighrs, so far not one of the staff had thought to offer us a complementary apperitif before dinner! We didn't have time just then, but we promised faithfully to appear in time for our apperitif the next night, i.e., last night, the night we wound up going straight to the restaurant and never got back to the hotel before dinner at all. So we apologized for standing them up, and they apologized for our never getting our complimentary apperitif. In the end, they struck all phone charges off our bill to make up for it, a nice gesture, I thought.

Once we got all our luggage down (and up, and across) all those stairs and out to the car, we bid Beaune a fond farewell and backtracked again to Nuits-St.-Georges to visit Cassisium, the museum and factory tour at the headquarters of the Védrenne liqueur and fruit-syrup company, which we found by following a long series of signs into and through the rather industrial back yard of the town.

Once we got all our luggage down (and up, and across) all those stairs and out to the car, we bid Beaune a fond farewell and backtracked again to Nuits-St.-Georges to visit Cassisium, the museum and factory tour at the headquarters of the Védrenne liqueur and fruit-syrup company, which we found by following a long series of signs into and through the rather industrial back yard of the town.

Inside the sleek modern building, we were invited to explore the black currant/cassis museum until time for our guided tour. When was that, we asked—anytime we liked, they said, because we were the only ones there. The museum began, as usual with the history of the cultivation of black currants in the world and in France; they've been around, and highly esteemed, for a long time, initially for medicinal use and later as a a flavor sought in its own right.

Written 3 July 2009

The museum had a large collection of mementos from early days of the marketing of the many competing brands of crême de cassis. One popular place to advertise was on the ceramic match holders that once graced every café table (right next to the ash trays) before the invention of the paper safety match, and the museum has dozens, as well as a large collection of crême de cassis bottles (from tiny pocket-sized ones to magnums) and many old-fashioned pieces of equipment for processing the currants. Each household in the area once had its own press for extracting the juice. In contrast to presses like "the Stubborn" the sizes of small houses, these were little table-top models, mostly cast iron, some as small as a no. 2 can. The rest of the apparatus was much like that for jelly-making, such as conical strainers with muslin liners for filtering the juice.

One unique feature of the museum was a "scent organ"—a three-sided contraption that, at the press of a button, emitted a puff of scent. One could choose among cassis juice, black currant sprouts, or finished crême de cassis.

One unique feature of the museum was a "scent organ"—a three-sided contraption that, at the press of a button, emitted a puff of scent. One could choose among cassis juice, black currant sprouts, or finished crême de cassis.

A large area of the museum was devoted to collections of black-currant products, demonstrating the fruit's versatility and world-wide popularity. This case is one of several devoted just to crême de cassis, i.e., black-currant liqueur of about 20% alcohol content. Other cases featured fruit syrups of many brands, candy, cookies, jellies and jams, and soft drinks—I was surprised to see that such familiar brands as Fanta and CapriSun come in black currant; we never see those flavors in the U.S. (or at least not in Tallahassee).

We were about three-quarters of the way through the museum when the young woman—our guide, as it turned out—came to ask if we would be pleased to have our tour now, with another couple who had arrived and wanted to do their tour first. We were happy to, so we followed her back to the front desk where the others, older French folks, were waiting. She then offered us the choice of doing our tour independently, with audioguides, or of having a live tour, with her, and she seemed a little dismayed when all four of us said, "why, with you, of course!" It turns out she was German, the usual French guide was on vacation, and this would be her very first tour conducted in French. We assured her we were all ears, that we weren't there to ferret out her deficiences, and not to be nervous. She did very well, using large note cards she had prepared for the purpose, and faltered only in not being able to think of one word—the source of the alcohol used in the brewing process—not grapes, not grain, a sort of underground vegetable, not potatoes.

Here she is, with her note cards, explaining the brewing process in front of old-fashioned apparatus now used only for the display. The real work now takes place in the room at the right, in stainless steel. The item at the right, a large cylinder lying on its side and viewed end-on, is a press. Those onthe left are maceration tanks.

Here she is, with her note cards, explaining the brewing process in front of old-fashioned apparatus now used only for the display. The real work now takes place in the room at the right, in stainless steel. The item at the right, a large cylinder lying on its side and viewed end-on, is a press. Those onthe left are maceration tanks.

Crême de cassis can be made by either of two processes, fermention and maceration. In the former, the crushed currants are fermented, just as grapes would be, and the finished "wine" is sweetened and adjusted to the proper alcohol content before bottling. Védrenne uses only the latter. The currants are roughly crushed, then macerated for a week or two with alcohol from other sources. The mixture is then pressed, and the juice is allowed to settle, then filtered. Sugar is added, and the alcohol content is adjusted before bottling (we couldn't watch the bottling; again, they weren't set up both to maintain proper sanitation and to allow spectators. The other couple then asked a question we often hear from the French on such tours: was the liqueur sweetened with cane sugar or beet sugar? "That's it!" the guide cried, "the missing word. Both the alcohol and the sugar come from beets!" So somewhere, presumably in those big processing plants we've seen in sugar-beet country, somebody is making beet wine (or beet beer?) and distilling it. I'm surprised we haven't come across beet brandy.

After the tour, we resumed our progress through the museum, then reported to the counter at the end for our tasting. Védrenne makes many, many more products, beyond crême de cassis, but they fall into three groups: fruit liqueurs, fruit syrups, and marc and fine. The fruit liqueurs are all made just like the créme de cassis, but with other fruits, and the company makes dozens— every fruit you can think of, mint, and even some nuts. The fruit syrups are just like the cémes but nonalcoholic; the fruit is just macerated with sugar. The marc and fine are brandy-like concoctions made, respectively, from the leftover seeds, skins, stems, etc. from winemaking and from the lees that settle out of wine as it is aged, both (as you can imagine) plentifully available in this area). David tasted both, declaring the marc foul but the fine not bad. I tasted a couple of the syrups, which are served diluted with water to make noncarbonated soft drinks. You never see them on menus (they don't list "salt" or "tap water" either), but every bar has a selection. They didn't have anything like the "ratafia de cassis" that I tasted at Bouchard Ainé.

Lunchtime, and here we were back in Nuits-St.-Georges. Parking downtown was free, because even the meter maids around here take two-hour lunches. The pay-and-display is only in force 9:00 a.m. to noon and 2:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. I got a better shot of the ornamental bunches of street grapes, and we ordered the usual salads with great slabs of cheese melted over them, and there they were again, the peppery-flavored little sprouts that are so popular this year. So I button-holed the waitress—what are these? "Leeks, Madame, sprouted leeks." How very French! I wonder if I can get untreated leek seeds in Tallahassee . . . I forewent dessert, because I still had those two little apricots I'd bought in the market in Beaune. I ate them as we drove out of town, and they were, hands-down, the best fresh apricots I have ever tasted—sweet, tender, fragrant, and juicy. Wow.

Lunchtime, and here we were back in Nuits-St.-Georges. Parking downtown was free, because even the meter maids around here take two-hour lunches. The pay-and-display is only in force 9:00 a.m. to noon and 2:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. I got a better shot of the ornamental bunches of street grapes, and we ordered the usual salads with great slabs of cheese melted over them, and there they were again, the peppery-flavored little sprouts that are so popular this year. So I button-holed the waitress—what are these? "Leeks, Madame, sprouted leeks." How very French! I wonder if I can get untreated leek seeds in Tallahassee . . . I forewent dessert, because I still had those two little apricots I'd bought in the market in Beaune. I ate them as we drove out of town, and they were, hands-down, the best fresh apricots I have ever tasted—sweet, tender, fragrant, and juicy. Wow.

At this point, it was time to leave the Côte d'Or and, in our endless pursuit of knowledge (and restaurants), to explore other parts of Burgundy—it's not all wine country. Accordingly, we turned east; climbed up one of those rocky, wooded ravines; and set off into the Morvan, the wooded, mountainous area behind the golden hillsides. We were headed for Saulieu, not a very big town but located at a very important crossroads. It was a major coaching stop long before modern means of transportation. It has an "borne impériale " (a little obelisk marking it as an official stop on Napoleon's state travels), Madame de Sévigné stayed here regularly when she travelled to visit friends further west, and it remains a popular stop with automobile travellers. Accordingly, it has a long history of gastronomy way above the level you'd expected in such a relatively small and isolated place.

We had dinner reservations at the Relais Bernard Loiseau (a GM 17/20; "relais" means "relay," as in the place where coaches stopped to change horses). It's also a hotel, but we stayed the night next door, at the Hôtel de la Poste (so named because it was a hotel back when the mail coaches stopped to change horses), at a fraction of the price. The relais was immediately to my left as I photographed the hotel.

We had dinner reservations at the Relais Bernard Loiseau (a GM 17/20; "relais" means "relay," as in the place where coaches stopped to change horses). It's also a hotel, but we stayed the night next door, at the Hôtel de la Poste (so named because it was a hotel back when the mail coaches stopped to change horses), at a fraction of the price. The relais was immediately to my left as I photographed the hotel.

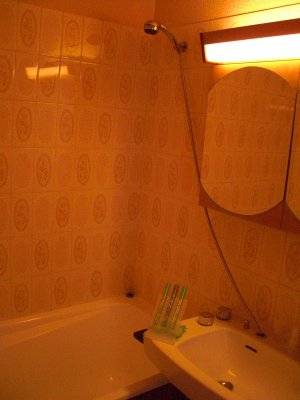

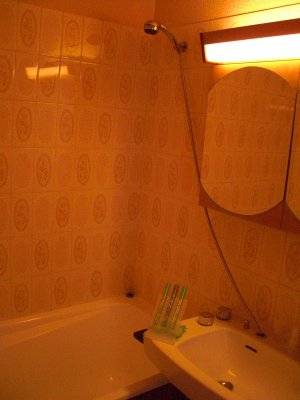

Our hotel had a variation on plumbing arrangements that I had never seen before—the sink and the shower shared a faucet/shower head! The left-hand photo shows things in the "sink" configuration. The knobs to the left of the shower head turn the water on and off. The right-hand photo shows them in the "shower" configuration—to use the shower, you pull the shower head out of the sink, on its long metal hose, and stick in into a little bracket mounted on the wall for the purpose. The sink and shower also share a soap dish, the black object mounted on the far side of the sink. When you want to fill the tub without using the shower, you use a separate set of knobs (out of sight on the far side of the sink) to turn on water that pours out of the bottom of the soap dish. Finally, a third set of knobs (apparently inactive) is mounted on the outside of the tub near the opposite end. Some unused fittings there make me hypothesize that they were intended to control the water in a bidet that was never installed. Amazing.

Our hotel had a variation on plumbing arrangements that I had never seen before—the sink and the shower shared a faucet/shower head! The left-hand photo shows things in the "sink" configuration. The knobs to the left of the shower head turn the water on and off. The right-hand photo shows them in the "shower" configuration—to use the shower, you pull the shower head out of the sink, on its long metal hose, and stick in into a little bracket mounted on the wall for the purpose. The sink and shower also share a soap dish, the black object mounted on the far side of the sink. When you want to fill the tub without using the shower, you use a separate set of knobs (out of sight on the far side of the sink) to turn on water that pours out of the bottom of the soap dish. Finally, a third set of knobs (apparently inactive) is mounted on the outside of the tub near the opposite end. Some unused fittings there make me hypothesize that they were intended to control the water in a bidet that was never installed. Amazing.

We took an initial turn on foot around the middle of town to see the famous François Pompon Bull and the decorative planting, and I wanted to look at the church and to visit the François Pompon museum, but it was threatening to rain, and David preferred to take a nap, so he went back to the hotel while I went on alone.

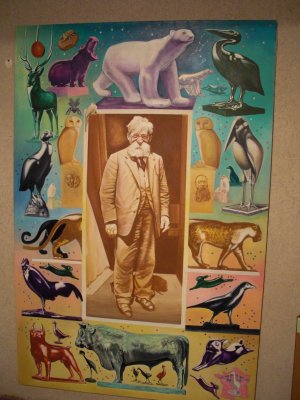

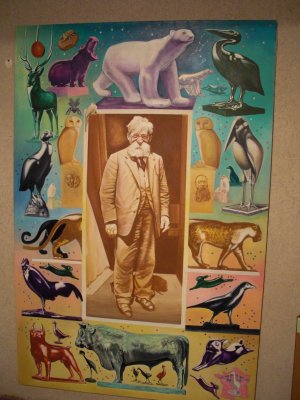

François Pompon, who lived and worked in Saulieu, is famous for his animal sculptures, of which the bull is the best known. The local museum is named for him and shows a good deal of his work and the story of his life, but I was surprised to find many other things there as well. In particular, Franck Rouilly, a modern artist specializing in what he called "monstratures" had a show running together with, and mixed in among, the Pompon works.

François Pompon, who lived and worked in Saulieu, is famous for his animal sculptures, of which the bull is the best known. The local museum is named for him and shows a good deal of his work and the story of his life, but I was surprised to find many other things there as well. In particular, Franck Rouilly, a modern artist specializing in what he called "monstratures" had a show running together with, and mixed in among, the Pompon works.

On the left, an English bulldog by Pompon. On the right, a view down into the courtyard where several of Rouilly's larger works were placed (not the two-legged ones). On the whole, I preferred Pompon and didn't much are for Rouilly's plaster-and-tile mosaic creatures, but a couple of the smaller Rouillys were great! I especially liked the scouring-pad-and-toothbrush bird and the saran-wrap-and-whole-coconut mosquito (which looks more like a fly to me), though in the long term, I'd rather look at the Pompon pelican every day.

On the left, an English bulldog by Pompon. On the right, a view down into the courtyard where several of Rouilly's larger works were placed (not the two-legged ones). On the whole, I preferred Pompon and didn't much are for Rouilly's plaster-and-tile mosaic creatures, but a couple of the smaller Rouillys were great! I especially liked the scouring-pad-and-toothbrush bird and the saran-wrap-and-whole-coconut mosquito (which looks more like a fly to me), though in the long term, I'd rather look at the Pompon pelican every day.

Other sections of the museum covered such disparate topics as rural crafts and pursuits—straw beehives (the area produces a lot of honey); the making of wooden shoes both by hand and on a large, elaborate, cast-iron apparatus that I couldn't figure out the workings of; reaping, threshing, and winnowing (aha! the wooden machine on the porch at l'Orée des Vignes was a winnower); the serious problem that wolves used to present and measures taken to deal with them (traps, spiked dog collars, and special lanterns designed to be particularly frightening to wolves); and the history of local restaurants. Several chefs have established national reputations in Saulieu, of which the two most famous are Alexandre Dumaine ("The chef of kings and the king of chefs!"; a memorial to him stands across the road from tonight's restaurant) and Bernard Loiseau.

Other sections of the museum covered such disparate topics as rural crafts and pursuits—straw beehives (the area produces a lot of honey); the making of wooden shoes both by hand and on a large, elaborate, cast-iron apparatus that I couldn't figure out the workings of; reaping, threshing, and winnowing (aha! the wooden machine on the porch at l'Orée des Vignes was a winnower); the serious problem that wolves used to present and measures taken to deal with them (traps, spiked dog collars, and special lanterns designed to be particularly frightening to wolves); and the history of local restaurants. Several chefs have established national reputations in Saulieu, of which the two most famous are Alexandre Dumaine ("The chef of kings and the king of chefs!"; a memorial to him stands across the road from tonight's restaurant) and Bernard Loiseau.

Loiseau died four or five years ago, in his 30s, but his wife, the souschef, and the hotel/restaurant team decided to carry on without him and to retain the name. He was apparently a very well-known and popular figure in the town. A whole room is devoted to him, featuring a table set with his personalized china and covered by a transparent dome, photos of him lounging astride the Pompon bull or riding his antique motorcycle (which is also there in the room). Mrs. Loiseau has even established branches of the restaurant in Beaune and Paris. At a boutique next door to the restaurant, you can buy that china, as well as many of the restaurant's trademark serving pieces; luckily, it was closed, so I wasn't tempted.

I had hoped to stop in to look at the church on the way back to the hotel, but a wedding was in progress, so I tiptoed in, staying out of the line of site, to take just one photo. David had gotten this shot of the bride, awaiting her cue, on his way past earlier.

I had hoped to stop in to look at the church on the way back to the hotel, but a wedding was in progress, so I tiptoed in, staying out of the line of site, to take just one photo. David had gotten this shot of the bride, awaiting her cue, on his way past earlier.

In the lounge, where we started with an apperitif before proceeding to the table, I was particularly struck by a piece of art consisting of a large, wide, rough-sawn plank out of which had been cut the life-size outline of a cello. The inside edges of the cut had been polished and varnished, just like the surface of a finished cello. Beautiful. With our drinks we were first served gougères that, rather than being baked individually, were slices out of a long strip. Equally tasty, though. Next came a more formal amuse-bouche: this season's usual cromesqui of pig's foot and, far more interesting, a little glass containing a stiffly gelled consommé of crustaceans topped with whipped cream and fried celery leaves. It was excellent! It was so concentrated it was the color of coffee, but the crustacean flavor was wonderful.

The dining room looked out on three sides through floor-to-ceiling windows, about eight feet above the ground, onto the hotel's beautiful informal garden.

The menu was divided between dishes by the new head chef and the classics of Bernard Loiseau. We chose the all-classic menu. The table was set with a special divided tray that provided space for a flat square of sweet butter from the Jura, a tall cylindrical china container of demisel butter from Poitou-Charentes, and a dish of sel de Guerand (special sea salt from Guerand).

Amuse-bouche: Cold, emulsified soup of artichokes with bacon bits and crisp artichoke chips. Delicious!

First course: Frog-leg "lollipops" with parsley sauce and a delicious mild purée of garlic. Scrumptious! (And much neater to eat than entire fried frogs, although they specified that we were supposed to use our fingers and brought fingerbowls afterward.)

First course: Frog-leg "lollipops" with parsley sauce and a delicious mild purée of garlic. Scrumptious! (And much neater to eat than entire fried frogs, although they specified that we were supposed to use our fingers and brought fingerbowls afterward.)

Second course: Crispy-skinned sandre (Lucioperca lucioperca, a freshwater pikeperch we're very fond of) on a heap of tender braised shallots and surrounded by a red wine sauce. It seems so simple, but I should be so lucky as to be able to produce a wine sauce that tasted that good and went that well with the fish!

Third course: Farm-raised chicken breast and sautéd foie gras with whole baby leeks and truffled mashed potatoes, all with a rich poultry reduction sauce with truffle crumbs. Yum!

Third course: Farm-raised chicken breast and sautéd foie gras with whole baby leeks and truffled mashed potatoes, all with a rich poultry reduction sauce with truffle crumbs. Yum!

Cheese, David: Brillat-Savarin, Roquefort, and Cˆiteaux. Cheese, me: An almost liquid St. Maur, Cîteaux, and Charolais. (I was pleased finally to see a liquifying chevre, but it turned out to be a disappointment. It had gotten acrid and ammonic in the process, whereas I know cheese like that can be ripened to liquidity and remain sweet and mild.) With the cheese came nut bread, fig bread, and this basket of Italian hazelnuts and dried Turkish figs.

Predessert: A verrine of, from the bottom up, mango purée, grapefruit and rose granité, and szechuan-pepper foam.

Predessert: A verrine of, from the bottom up, mango purée, grapefruit and rose granité, and szechuan-pepper foam.

Dessert: "Rose des sables" of chocolate cookies and chocolate ganache. A "rose des sables" (sand rose or desert rose) is crystallized gypsum—just Google-image the phrase for lots of photos—a mineral this dessert mimics the shape of. Delicious, especially the thin chocolate cookies, but the ganache was so intensely chocolate that I couldn't eat half of it. It certainly looks spectacular on the plate, though! The sauce is a purée of sweet stewed oranges, a very good combination with the chocolate.

The mignardises were more interesting than some. Besides the usual almond tuiles and tiny fruit tarts, the square pink things with blueberries on top are (airbrushed) white chocolate mousse, the little domes are ginger flavored, and the chocolates are filled with tarragon cream and a candied cherry! I wanted to taste the tarragon chocolates, but before eating one, I had to spend time scraping off every last fleck of the gold leaf somebody had seen fit to stick to the cherry—it's supposed to be edible, but getting the tiniest piece of it on a lead-amalgam filling is horrible!

The mignardises were more interesting than some. Besides the usual almond tuiles and tiny fruit tarts, the square pink things with blueberries on top are (airbrushed) white chocolate mousse, the little domes are ginger flavored, and the chocolates are filled with tarragon cream and a candied cherry! I wanted to taste the tarragon chocolates, but before eating one, I had to spend time scraping off every last fleck of the gold leaf somebody had seen fit to stick to the cherry—it's supposed to be edible, but getting the tiniest piece of it on a lead-amalgam filling is horrible!

Mrs. Loiseau was chatting with guests in the lobby when we left and came over to shake our hands and thank us for coming.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Once we got all our luggage down (and up, and across) all those stairs and out to the car, we bid Beaune a fond farewell and backtracked again to Nuits-St.-Georges to visit Cassisium, the museum and factory tour at the headquarters of the Védrenne liqueur and fruit-syrup company, which we found by following a long series of signs into and through the rather industrial back yard of the town.

Once we got all our luggage down (and up, and across) all those stairs and out to the car, we bid Beaune a fond farewell and backtracked again to Nuits-St.-Georges to visit Cassisium, the museum and factory tour at the headquarters of the Védrenne liqueur and fruit-syrup company, which we found by following a long series of signs into and through the rather industrial back yard of the town. One unique feature of the museum was a "scent organ"—a three-sided contraption that, at the press of a button, emitted a puff of scent. One could choose among cassis juice, black currant sprouts, or finished crême de cassis.

One unique feature of the museum was a "scent organ"—a three-sided contraption that, at the press of a button, emitted a puff of scent. One could choose among cassis juice, black currant sprouts, or finished crême de cassis.

Here she is, with her note cards, explaining the brewing process in front of old-fashioned apparatus now used only for the display. The real work now takes place in the room at the right, in stainless steel. The item at the right, a large cylinder lying on its side and viewed end-on, is a press. Those onthe left are maceration tanks.

Here she is, with her note cards, explaining the brewing process in front of old-fashioned apparatus now used only for the display. The real work now takes place in the room at the right, in stainless steel. The item at the right, a large cylinder lying on its side and viewed end-on, is a press. Those onthe left are maceration tanks.

Lunchtime, and here we were back in Nuits-St.-Georges. Parking downtown was free, because even the meter maids around here take two-hour lunches. The pay-and-display is only in force 9:00 a.m. to noon and 2:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. I got a better shot of the ornamental bunches of street grapes, and we ordered the usual salads with great slabs of cheese melted over them, and there they were again, the peppery-flavored little sprouts that are so popular this year. So I button-holed the waitress—what are these? "Leeks, Madame, sprouted leeks." How very French! I wonder if I can get untreated leek seeds in Tallahassee . . . I forewent dessert, because I still had those two little apricots I'd bought in the market in Beaune. I ate them as we drove out of town, and they were, hands-down, the best fresh apricots I have ever tasted—sweet, tender, fragrant, and juicy. Wow.

Lunchtime, and here we were back in Nuits-St.-Georges. Parking downtown was free, because even the meter maids around here take two-hour lunches. The pay-and-display is only in force 9:00 a.m. to noon and 2:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. I got a better shot of the ornamental bunches of street grapes, and we ordered the usual salads with great slabs of cheese melted over them, and there they were again, the peppery-flavored little sprouts that are so popular this year. So I button-holed the waitress—what are these? "Leeks, Madame, sprouted leeks." How very French! I wonder if I can get untreated leek seeds in Tallahassee . . . I forewent dessert, because I still had those two little apricots I'd bought in the market in Beaune. I ate them as we drove out of town, and they were, hands-down, the best fresh apricots I have ever tasted—sweet, tender, fragrant, and juicy. Wow.

We had dinner reservations at the Relais Bernard Loiseau (a GM 17/20; "relais" means "relay," as in the place where coaches stopped to change horses). It's also a hotel, but we stayed the night next door, at the Hôtel de la Poste (so named because it was a hotel back when the mail coaches stopped to change horses), at a fraction of the price. The relais was immediately to my left as I photographed the hotel.

We had dinner reservations at the Relais Bernard Loiseau (a GM 17/20; "relais" means "relay," as in the place where coaches stopped to change horses). It's also a hotel, but we stayed the night next door, at the Hôtel de la Poste (so named because it was a hotel back when the mail coaches stopped to change horses), at a fraction of the price. The relais was immediately to my left as I photographed the hotel.

Our hotel had a variation on plumbing arrangements that I had never seen before—the sink and the shower shared a faucet/shower head! The left-hand photo shows things in the "sink" configuration. The knobs to the left of the shower head turn the water on and off. The right-hand photo shows them in the "shower" configuration—to use the shower, you pull the shower head out of the sink, on its long metal hose, and stick in into a little bracket mounted on the wall for the purpose. The sink and shower also share a soap dish, the black object mounted on the far side of the sink. When you want to fill the tub without using the shower, you use a separate set of knobs (out of sight on the far side of the sink) to turn on water that pours out of the bottom of the soap dish. Finally, a third set of knobs (apparently inactive) is mounted on the outside of the tub near the opposite end. Some unused fittings there make me hypothesize that they were intended to control the water in a bidet that was never installed. Amazing.

Our hotel had a variation on plumbing arrangements that I had never seen before—the sink and the shower shared a faucet/shower head! The left-hand photo shows things in the "sink" configuration. The knobs to the left of the shower head turn the water on and off. The right-hand photo shows them in the "shower" configuration—to use the shower, you pull the shower head out of the sink, on its long metal hose, and stick in into a little bracket mounted on the wall for the purpose. The sink and shower also share a soap dish, the black object mounted on the far side of the sink. When you want to fill the tub without using the shower, you use a separate set of knobs (out of sight on the far side of the sink) to turn on water that pours out of the bottom of the soap dish. Finally, a third set of knobs (apparently inactive) is mounted on the outside of the tub near the opposite end. Some unused fittings there make me hypothesize that they were intended to control the water in a bidet that was never installed. Amazing.

François Pompon, who lived and worked in Saulieu, is famous for his animal sculptures, of which the bull is the best known. The local museum is named for him and shows a good deal of his work and the story of his life, but I was surprised to find many other things there as well. In particular, Franck Rouilly, a modern artist specializing in what he called "monstratures" had a show running together with, and mixed in among, the Pompon works.

François Pompon, who lived and worked in Saulieu, is famous for his animal sculptures, of which the bull is the best known. The local museum is named for him and shows a good deal of his work and the story of his life, but I was surprised to find many other things there as well. In particular, Franck Rouilly, a modern artist specializing in what he called "monstratures" had a show running together with, and mixed in among, the Pompon works.

On the left, an English bulldog by Pompon. On the right, a view down into the courtyard where several of Rouilly's larger works were placed (not the two-legged ones). On the whole, I preferred Pompon and didn't much are for Rouilly's plaster-and-tile mosaic creatures, but a couple of the smaller Rouillys were great! I especially liked the scouring-pad-and-toothbrush bird and the saran-wrap-and-whole-coconut mosquito (which looks more like a fly to me), though in the long term, I'd rather look at the Pompon pelican every day.

On the left, an English bulldog by Pompon. On the right, a view down into the courtyard where several of Rouilly's larger works were placed (not the two-legged ones). On the whole, I preferred Pompon and didn't much are for Rouilly's plaster-and-tile mosaic creatures, but a couple of the smaller Rouillys were great! I especially liked the scouring-pad-and-toothbrush bird and the saran-wrap-and-whole-coconut mosquito (which looks more like a fly to me), though in the long term, I'd rather look at the Pompon pelican every day.

Other sections of the museum covered such disparate topics as rural crafts and pursuits—straw beehives (the area produces a lot of honey); the making of wooden shoes both by hand and on a large, elaborate, cast-iron apparatus that I couldn't figure out the workings of; reaping, threshing, and winnowing (aha! the wooden machine on the porch at l'Orée des Vignes was a winnower); the serious problem that wolves used to present and measures taken to deal with them (traps, spiked dog collars, and special lanterns designed to be particularly frightening to wolves); and the history of local restaurants. Several chefs have established national reputations in Saulieu, of which the two most famous are Alexandre Dumaine ("The chef of kings and the king of chefs!"; a memorial to him stands across the road from tonight's restaurant) and Bernard Loiseau.

Other sections of the museum covered such disparate topics as rural crafts and pursuits—straw beehives (the area produces a lot of honey); the making of wooden shoes both by hand and on a large, elaborate, cast-iron apparatus that I couldn't figure out the workings of; reaping, threshing, and winnowing (aha! the wooden machine on the porch at l'Orée des Vignes was a winnower); the serious problem that wolves used to present and measures taken to deal with them (traps, spiked dog collars, and special lanterns designed to be particularly frightening to wolves); and the history of local restaurants. Several chefs have established national reputations in Saulieu, of which the two most famous are Alexandre Dumaine ("The chef of kings and the king of chefs!"; a memorial to him stands across the road from tonight's restaurant) and Bernard Loiseau.

I had hoped to stop in to look at the church on the way back to the hotel, but a wedding was in progress, so I tiptoed in, staying out of the line of site, to take just one photo. David had gotten this shot of the bride, awaiting her cue, on his way past earlier.

I had hoped to stop in to look at the church on the way back to the hotel, but a wedding was in progress, so I tiptoed in, staying out of the line of site, to take just one photo. David had gotten this shot of the bride, awaiting her cue, on his way past earlier.

First course: Frog-leg "lollipops" with parsley sauce and a delicious mild purée of garlic. Scrumptious! (And much neater to eat than entire fried frogs, although they specified that we were supposed to use our fingers and brought fingerbowls afterward.)

First course: Frog-leg "lollipops" with parsley sauce and a delicious mild purée of garlic. Scrumptious! (And much neater to eat than entire fried frogs, although they specified that we were supposed to use our fingers and brought fingerbowls afterward.)

Third course: Farm-raised chicken breast and sautéd foie gras with whole baby leeks and truffled mashed potatoes, all with a rich poultry reduction sauce with truffle crumbs. Yum!

Third course: Farm-raised chicken breast and sautéd foie gras with whole baby leeks and truffled mashed potatoes, all with a rich poultry reduction sauce with truffle crumbs. Yum!

Predessert: A verrine of, from the bottom up, mango purée, grapefruit and rose granité, and szechuan-pepper foam.

Predessert: A verrine of, from the bottom up, mango purée, grapefruit and rose granité, and szechuan-pepper foam. The mignardises were more interesting than some. Besides the usual almond tuiles and tiny fruit tarts, the square pink things with blueberries on top are (airbrushed) white chocolate mousse, the little domes are ginger flavored, and the chocolates are filled with tarragon cream and a candied cherry! I wanted to taste the tarragon chocolates, but before eating one, I had to spend time scraping off every last fleck of the gold leaf somebody had seen fit to stick to the cherry—it's supposed to be edible, but getting the tiniest piece of it on a lead-amalgam filling is horrible!

The mignardises were more interesting than some. Besides the usual almond tuiles and tiny fruit tarts, the square pink things with blueberries on top are (airbrushed) white chocolate mousse, the little domes are ginger flavored, and the chocolates are filled with tarragon cream and a candied cherry! I wanted to taste the tarragon chocolates, but before eating one, I had to spend time scraping off every last fleck of the gold leaf somebody had seen fit to stick to the cherry—it's supposed to be edible, but getting the tiniest piece of it on a lead-amalgam filling is horrible!