Friday, 19 June 2009, Cluny in the rain

Written 2 July 2009

Not a day that went as planned, but hey, it's all an adventure, right? This was our last full day in Beaune, and we had decided to spend it making an excursion to Cluny, to see the famous abbey that used to be there. The distance was kind of a reach (Cluny is well south of Chalons), but if you're going around visiting abbeys, you really can't skip Cluny. Our route led south out of Beaune, through Chagny, where we had dinner reservations, and for part of the way along the Canal du Centre, another picturesque but little-used waterway. I also had a chance to photograph one of the local vine tractors, designed to straddle two rows of vines. If you compare this one the one in last-year's diary of our trip to Champagne, you'll see that this one is not as tall—vines are trained shorter in Burgundy.

Not a day that went as planned, but hey, it's all an adventure, right? This was our last full day in Beaune, and we had decided to spend it making an excursion to Cluny, to see the famous abbey that used to be there. The distance was kind of a reach (Cluny is well south of Chalons), but if you're going around visiting abbeys, you really can't skip Cluny. Our route led south out of Beaune, through Chagny, where we had dinner reservations, and for part of the way along the Canal du Centre, another picturesque but little-used waterway. I also had a chance to photograph one of the local vine tractors, designed to straddle two rows of vines. If you compare this one the one in last-year's diary of our trip to Champagne, you'll see that this one is not as tall—vines are trained shorter in Burgundy.

Where no vines were planted, we saw Charolais cattle, some colza, and some young corn. In just one place, a few of the first sunflowers were beginning to come into bloom. Near Givry, we passed an unusual sawmill, where very large logs had been sawn into thick planks, but instead of being planed down and stacked like lumber, the planks forming each tree trunk had been carefully reassembled into their original cylindrical shape, spaced slightly apart by little wooden blocks. What for? We wondered whether barrel makers might want to choose contiguous planks for the same barrel, but the place turned out to be a parquet factory, in which grain-matched pieces of wood flooring are arranged to form geometrical patterns!

Near St. Gengoux le National (I wonder what that name signifies), a squirrel jumped out in front of the car and ran along ahead of us for a short ways before jumping safely back into the hedge. Its color made clear what the poster-makers were on about when they named a wine color "squirrel"—from what I could see, it looked much like our (actually imported) gray squirrels except that it was the most beautiful auburn red; I'd never seen one like that before!

The rain started about noon as we approached Cormantin, just about the time road construction sent us off the secondary road we were already following on a long detour through the tiny villages of Lys, Chasseaux, Bray, and Toury before we were able to get back on track. In one village, we passed a place advertising that it made goat cheese, but we saw no goats. None of these places them offered any lunch prospects, so that was our second priority on reaching Cluny, after finding a gas station. Our route to fuel took us right by a likely looking restaurant called Le Rochefort that proudly specialized in frogs' legs, so on the way back by, we stopped in.

David ordered the usual salad—lardons, croutons, poached egg—but I couldn't resist the speciality. Imagine my surprise when I got a sizzling heap, a full dozen, not of frogs' legs, as the menu described them, but of entire, crispy deep- fried frogs! In the photo, I've pulled one out of the pile. It's presented in dorsal view, with its ankles folded up behind the small of its back. They were dressed with parsley butter as promised and sided with a fat slice of lemon. Delicious! On the right, you can see what I had left when I finished with them. I ate as fast as I could, and David was very tolerant. The people at the next table had their dog with them (as did those opposite us), and at the end of their meal, they sent their plates back to the kitchen, where the scraps were gathered into a little covered doggy dish, which was brought back and set on the floor for their dog to finish up. The lady opposite us had brought her little white dog (a peekapoo maybe?) into the restaurant tucked under her arm like a rag doll and set it on an empty chair at their table, where it sat happily throughout the meal (they ordered specially for it, rather than feeding it their scraps; the waitress set the dish on the chair) until, at the end, she picked it up, tucked it under her arm, and carried it away with her. Its feet never touched the ground, and it seemed perfectly content with the arrangement. The two dogs, perhaps 10 feet apart the whole time, never showed the slightest interest in each other.

David ordered the usual salad—lardons, croutons, poached egg—but I couldn't resist the speciality. Imagine my surprise when I got a sizzling heap, a full dozen, not of frogs' legs, as the menu described them, but of entire, crispy deep- fried frogs! In the photo, I've pulled one out of the pile. It's presented in dorsal view, with its ankles folded up behind the small of its back. They were dressed with parsley butter as promised and sided with a fat slice of lemon. Delicious! On the right, you can see what I had left when I finished with them. I ate as fast as I could, and David was very tolerant. The people at the next table had their dog with them (as did those opposite us), and at the end of their meal, they sent their plates back to the kitchen, where the scraps were gathered into a little covered doggy dish, which was brought back and set on the floor for their dog to finish up. The lady opposite us had brought her little white dog (a peekapoo maybe?) into the restaurant tucked under her arm like a rag doll and set it on an empty chair at their table, where it sat happily throughout the meal (they ordered specially for it, rather than feeding it their scraps; the waitress set the dish on the chair) until, at the end, she picked it up, tucked it under her arm, and carried it away with her. Its feet never touched the ground, and it seemed perfectly content with the arrangement. The two dogs, perhaps 10 feet apart the whole time, never showed the slightest interest in each other.

After lunch, we drove into the edges of Cluny and when we began to see signs for the abbey, we pulled into a parking lot and set off on foot, through the light rain. We followed the signs up the hill through a sort of park to the back of the museum building, then around it to the front, where we bought tour tickets and explored the gift shop and adjoining museum until the tour started. The gift shop had a couple of books I wouldn't mind owing: Inventaire des Dictons des Terroirs de la France (Inventory of the Regional Folk Sayings of France sure enough, my "hailed and smoked vines" were in there) by Gabrielle Cosson and Histoire des Peurs Alimentaires du Moyen Age à l'Aube du Vingtième (History of Food Fears from the Middle Ages to the Dawn of the 20th Century) by Madeleine de Ferrières. Wow.

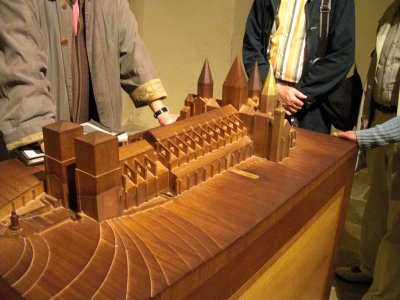

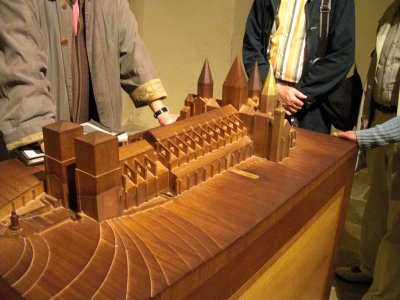

The Abbey of Cluny is difficult to photograph for the simple reason that it isn't there any more, but here are a couple of models to show what you're supposed to imagine. The one on the left shows the entire abbey complex, with part of the outer wall of the compound beyond. The one on the right shows only the abbey church and is designed for the blind. Out of the photo is an extensive braille explanation.

The Abbey of Cluny is difficult to photograph for the simple reason that it isn't there any more, but here are a couple of models to show what you're supposed to imagine. The one on the left shows the entire abbey complex, with part of the outer wall of the compound beyond. The one on the right shows only the abbey church and is designed for the blind. Out of the photo is an extensive braille explanation.

The Abbey was founded in 910 A.D. by Duke Guillaume d'Aquitaine, only 100 years after Charlemagne, and under its first six abbots (four of whom have since been canonized), it flourished. Remember back in world history they talked about how knowledge was preserved through the Dark Ages, kept alive in monastaries until it could reemerge during the Renaissance? Well, this is the place. It rivaled Rome in influence, and the abbey church was, in its time, the largest church in Christendom. If it were still standing, it will would be the second largest (after the Hagia Sophia); it dwarfed the other great cathedrals of France. German tourists frequently protest that the cathedral at Speyer is larger, but in fact, Cluny was 2 m longer, even without the narthex (the part with the lower roof), which was added long after the rest was completed.

Our excellent guide, a German who spoke only slightly accented French, usually leads the tours in German, but they were short of guides for the French tours this week. He explained that until the time of the "commendum" abbots were elected from within the brotherhood in the abbey and lived within the walls with the other monks, but then, during the commendum, the kings of France for a time claimed the right to appoint new abbots and frequently appointed them for political rather than religious reasons. Jean de Bourbon, illegitimate offspring of royalty, was appointed abbot in 1456 and was the first to live outside; in fact, he built himself a sumptuous palace, with tesselated tile floors of many different designs, against the outside of the compound wall—that building now houses the abbey's museum (signs and barricades warn you away from some areas near it because of the danger of falling roof tiles). The guide also emphasized that Cluny's prestige and power had already begun to deline by the 12th century. By the time of Jean de Bourbon, abuses like the ones St. Bernard and the Cistercians were reforming in protest of had become rife.

But Cluny continued to be an active monastery and abbey until the time of the revolution. It's extensive library (about 1800 volumes in the time of Jean de Bourbon) was burned, but it has been partially restored through donations. After the revolution, the buildings were claimed as property of the state and sold off (like so many of the castles) as a stone quarry. The purchaser was doing quite well out of the deal, dismantling the buildings as needed and selling off the stones, when people began to talk about saving and restoring the church—pointing out that, religion aside, it was a national architectural treasure, a historical education itself, etc.—and started appealing to the government for help. In the early 19th century, the purchaser, worried that his profitable property would be repossessed, figured, hey, no national treasure no point in restoration, aquired a large quantity of gunpowder, and blew it up.

Today, the only parts that remain are the south arms of the large and small transcepts, part of the cloister, and parts of the square towers at the other end. The town has closed in around them, and a large hotel now covers part of the nave and other transcept arms, so even archeological investigations are difficult. In the early 20th century, an American named Kenneth J. Conant did extensive archeological work, and much of the "virtual" reconstruction is based on his data. The photo at the left shows an absolutely brilliant idea—it's a computerized viewing screen that swivels 360o on its post and can be tilted up and down, and whichever way you point it, it shows a reconstructed view of what you would be looking at if the church were still standing! It's apparently brand new and still a little flaky sometimes, but this is an idea that I'll bet will catch on with historical reconstructions the world over! The tour guide is holding up his notebook, with a floor plan of the church, to demonstrate which part of it we're looking at on the viewer. The other photo is a section of the outer compound wall that's still standing.

Today, the only parts that remain are the south arms of the large and small transcepts, part of the cloister, and parts of the square towers at the other end. The town has closed in around them, and a large hotel now covers part of the nave and other transcept arms, so even archeological investigations are difficult. In the early 20th century, an American named Kenneth J. Conant did extensive archeological work, and much of the "virtual" reconstruction is based on his data. The photo at the left shows an absolutely brilliant idea—it's a computerized viewing screen that swivels 360o on its post and can be tilted up and down, and whichever way you point it, it shows a reconstructed view of what you would be looking at if the church were still standing! It's apparently brand new and still a little flaky sometimes, but this is an idea that I'll bet will catch on with historical reconstructions the world over! The tour guide is holding up his notebook, with a floor plan of the church, to demonstrate which part of it we're looking at on the viewer. The other photo is a section of the outer compound wall that's still standing.

By the time we were well into the tour, the rain had begun in earnest, so we were scurrying from sheltered spot to sheltered spot while the guide pointed out items of interest. We had been joined on the tour by a whole busload of French golden-agers, so several little old ladies had to be helped up and down all the stairs (one actually fell and twisted her knee, but she sat down for a while during the guide's narration, then carried on gamely with the rest of the tour). The guide rolled his eyes while pointing to areas in the still-standing transcept where a restoration project was scheduled to begin, grumbling "It's hard enough to lead guided tours of something that isn't there, without having scaffolding all over the 10% that still is!"

Finally, he led us across a stretch of gravel walk and lawn, in the pouring rain, sloshing through puddles, to climb yet another set of stairs into the vast building that served as the abbey's grain and flour storage. It's now used to display the carved capitals of a series of columns that Conant dug out of the rubble, but its real attraction is its magnificent wooden roof architecture. Naval carpenters were brought in to build what is essentially an inverted ship's hull. It's made mainly of oak but with some chestnut mixed in—chestnut repels insects, so it tends to result in better preservation of wooden structures. The whole thing has been there since the 13th century. A few years ago, our guide said, some people on the tour asked him whether the beams had been dated by dendrochronology, the first time he'd ever heard the word. He said almost certainly not, because it would require cutting through one of the beams. So the questioners, who were in fact dendrochronologists, went home and started the process of getting permission. Now the guide points out the beam that has had a short section removed, from which the dendrochronologists were able to ascertain that that particular tree was cut in the early spring of the year 1157!

By the time the tour was over, we we were beginning to worry about getting back to Beaune in time for our dinner reservations, so we left the abbey compound by the door the guide opened for us (and closed behind us), only to find ourselves in a completely unfamiliar street, in the pouring rain, without even any idea of where we were with respect to the museum or which way we were facing. Numerous nearby signs pointing in different directions to various parking lots made us realize we also had no idea of the name of our parking lot! Drat. Initially, David pointed out that we'd climbed into town from the parking lot, so we turned left and walked downhill, but we still didn't encounter anything that looked familiar. After a couple of blocks David spotted a sign pointing toward the town hall—didn't we walk past that on our way in? So we set off in that direction.

That worked, but before we came to anything we'd seen before we passed a bunch of other interesting stuff. For example, parts of the old monastery buildings now house the national school of "arts and metiers" (arts and occupations, shown at the left; I'm not sure just what constitutes an occupation, as opposed to a profession, but the students we passed seemed to be carrying architectural models; their "school uniform" is a long smock, almost like an academic gown, which they are free to decorate with all kinds of patches, pictures, writing, etc.). We also saw this war memorial inscribed "The victory of 1944 gives back to us hope and liberty." We even passed the Cluny branch of the national equestrian stud, which I had not realized existed. A sign on the gate offered guided tours, but this was about the third time we've discovered a national stud only after using up all the available time touring something else. Maybe next year . . .

That worked, but before we came to anything we'd seen before we passed a bunch of other interesting stuff. For example, parts of the old monastery buildings now house the national school of "arts and metiers" (arts and occupations, shown at the left; I'm not sure just what constitutes an occupation, as opposed to a profession, but the students we passed seemed to be carrying architectural models; their "school uniform" is a long smock, almost like an academic gown, which they are free to decorate with all kinds of patches, pictures, writing, etc.). We also saw this war memorial inscribed "The victory of 1944 gives back to us hope and liberty." We even passed the Cluny branch of the national equestrian stud, which I had not realized existed. A sign on the gate offered guided tours, but this was about the third time we've discovered a national stud only after using up all the available time touring something else. Maybe next year . . .

Eventually, we arrived at the town hall, and yes, from there we could find the car. We set out to retrace our path to Beaune, including the long detour south of Cormatin, and projecting ahead from our progress made increasingly clear that once we reached the hotel we would have maybe 20 minutes in which to shower and change before setting off for the restaurant in Chagny, which we would have just driven past on our way there. So we decided just to go straight to the restaurant. So what if we looked like drowned rats and would be about an hour early.

We arranged to drive into town on the one radius I was sure I could recognize on the little Mappy area map showing the restaurant's location. It worked like a charm, and we soon arrived at the very intersection marked by the little star only to find nothing that resembled a restaurant. Drat. Lost again. We parked the car, returned on foot to the wrong location (when Google or Mappy doesn't know an address, it just puts the star in the center of town, and that's clearly where we were). First, we tried walking in each direction a couple of blocks looking down side streets. No luck. Then we spotted a city map on a large signboard outside the (closed) town hall and scoured it for the hotel's address, which was simply "Place d'Armes" (usually the name given to the square in the dead center of the town). No luck. We looked for an open hotel or restaurant where we might ask. No luck. Finally, I presented myself in a bakery (it was then or never, as the last of the businesses were preparing to close) and asked the nice lady there where we might find the Restaurant Lamelloise. She said, just go down that street there and take a right; can't miss it. Off we went again, in a direction we'd already tried, but this time we went one block further before turning right—there, right in front of us, the street abruptly widened into a broad triangular "place" with a handsome fountain, all dominated by a three-story building with "Restaurant Lamelloise" across the front in lighted letters two feet high.

By that time, we were only half an hour early, so we just presented ourselves at the door as though everything were normal and my hair weren't sticking out in six directions and were ushered to our table without a murmur. We weren't even seriously underdressed. Once we had studied the choices and settled on the tasting menu (despite prices that were once again way higher than those in Beaune), I went to the ladies room, unbraided and fluffed my hair, then rebraided it, which helped a little. While I was gone, the first amuse-bouche arrived, and David, who, what with one thing and another, had been getting a little testy, cheered up and clowned around with my camera.

By that time, we were only half an hour early, so we just presented ourselves at the door as though everything were normal and my hair weren't sticking out in six directions and were ushered to our table without a murmur. We weren't even seriously underdressed. Once we had studied the choices and settled on the tasting menu (despite prices that were once again way higher than those in Beaune), I went to the ladies room, unbraided and fluffed my hair, then rebraided it, which helped a little. While I was gone, the first amuse-bouche arrived, and David, who, what with one thing and another, had been getting a little testy, cheered up and clowned around with my camera.

First amuse-bouche: (in the foreground), little mousses of liver with fig sauce on top, (behind) canapes topped with cherry-tomato slices and mozzarella domes, (in the background and definitely the best) tartare of tuna with bits of peanut and vinegar, and (in the glass) two kinds of "lollipops": Comté cheese on pastry strips and olive-and-pastry spirals on bamboo skewers.

Second amuse-bouche: Cold purées of zucchini and of tomato with cream, topped with a savory tuile cooky with almond bits on it and sided by a croquette of cod-and-potato purée. Excellent.

Second amuse-bouche: Cold purées of zucchini and of tomato with cream, topped with a savory tuile cooky with almond bits on it and sided by a croquette of cod-and-potato purée. Excellent.

A choice of breads was offered, and we both chose these buttery, flaky rolls made from croissant dough. Absolutely delicious, but they would have been better with breakfast than with dinner.

First course, both: Cold crab salad topped with a cold cooked shrimp and surrounded by cold asparagus gazpacho. We think the brownish arch with the neat round holes punched in it was a strip of dried rhubarb.

First course, both: Cold crab salad topped with a cold cooked shrimp and surrounded by cold asparagus gazpacho. We think the brownish arch with the neat round holes punched in it was a strip of dried rhubarb.

Second course, both: Slow-cooked turbot with herbs, with simmered purple artichokes and caramelized onion juice. Topped with a single crisp onion ring.

Third course, both: Lobster cooked in its shell with a lettuce cannelloni, wild asparagus, and "cardinal" sabayon (a fluffy, crustacean flavored hollandaise).

Third course, both: Lobster cooked in its shell with a lettuce cannelloni, wild asparagus, and "cardinal" sabayon (a fluffy, crustacean flavored hollandaise).

Fourth course, David: Breast and leg of pigeon poached in truffled consommé with the "vegetables of the moment." The little cheese-cloth sack was filled with herbs intended to flavor the hot broth poured over it at the table.

Fourth course, me: Sautéed veal sweetbreads with a sauce of roasted citrus peel, on a bed of chanterelles. On the side, a cylinder of potato that had been spiral-cut to let in the butter and the flavor of three kinds of pepper. All excellent.

Fourth course, me: Sautéed veal sweetbreads with a sauce of roasted citrus peel, on a bed of chanterelles. On the side, a cylinder of potato that had been spiral-cut to let in the butter and the flavor of three kinds of pepper. All excellent.

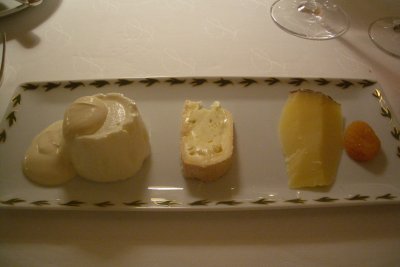

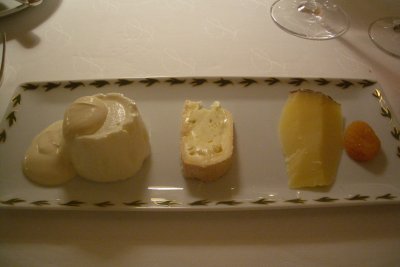

Cheese, David: Comté, Cîteaux, a faisselle of fromage blanc with heavy cream so thick the waiter had to drape it over the side of the cheese, and one dried apricot. He was offered sugar to put on the fromage blanc but opted for sea salt instead and declared it outstanding.

Cheese, me: Maconnais (a small, dry local goat cheese), Brillat-Savarin (the first we'd seen in days), Cîteaux, and one prune.

Predessert: An excellent miniature tiramisu served in a glass that really did lean at that angle.

Dessert: A flat timbale of stewed rhubarb topped with fresh strawberries and ice cream (I don't remember what kind!). The band around the base and the loop over the top are dried, sweetened slices of rhubarb, chewy but tasty, like rhubarb jerky

Finally, as we waited for the check, two rounds of mignardises, on the usual slate slabs—11 kinds in all.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Not a day that went as planned, but hey, it's all an adventure, right? This was our last full day in Beaune, and we had decided to spend it making an excursion to Cluny, to see the famous abbey that used to be there. The distance was kind of a reach (Cluny is well south of Chalons), but if you're going around visiting abbeys, you really can't skip Cluny. Our route led south out of Beaune, through Chagny, where we had dinner reservations, and for part of the way along the Canal du Centre, another picturesque but little-used waterway. I also had a chance to photograph one of the local vine tractors, designed to straddle two rows of vines. If you compare this one the one in last-year's diary of our trip to Champagne, you'll see that this one is not as tall—vines are trained shorter in Burgundy.

Not a day that went as planned, but hey, it's all an adventure, right? This was our last full day in Beaune, and we had decided to spend it making an excursion to Cluny, to see the famous abbey that used to be there. The distance was kind of a reach (Cluny is well south of Chalons), but if you're going around visiting abbeys, you really can't skip Cluny. Our route led south out of Beaune, through Chagny, where we had dinner reservations, and for part of the way along the Canal du Centre, another picturesque but little-used waterway. I also had a chance to photograph one of the local vine tractors, designed to straddle two rows of vines. If you compare this one the one in last-year's diary of our trip to Champagne, you'll see that this one is not as tall—vines are trained shorter in Burgundy.

David ordered the usual salad—lardons, croutons, poached egg—but I couldn't resist the speciality. Imagine my surprise when I got a sizzling heap, a full dozen, not of frogs' legs, as the menu described them, but of entire, crispy deep- fried frogs! In the photo, I've pulled one out of the pile. It's presented in dorsal view, with its ankles folded up behind the small of its back. They were dressed with parsley butter as promised and sided with a fat slice of lemon. Delicious! On the right, you can see what I had left when I finished with them. I ate as fast as I could, and David was very tolerant. The people at the next table had their dog with them (as did those opposite us), and at the end of their meal, they sent their plates back to the kitchen, where the scraps were gathered into a little covered doggy dish, which was brought back and set on the floor for their dog to finish up. The lady opposite us had brought her little white dog (a peekapoo maybe?) into the restaurant tucked under her arm like a rag doll and set it on an empty chair at their table, where it sat happily throughout the meal (they ordered specially for it, rather than feeding it their scraps; the waitress set the dish on the chair) until, at the end, she picked it up, tucked it under her arm, and carried it away with her. Its feet never touched the ground, and it seemed perfectly content with the arrangement. The two dogs, perhaps 10 feet apart the whole time, never showed the slightest interest in each other.

David ordered the usual salad—lardons, croutons, poached egg—but I couldn't resist the speciality. Imagine my surprise when I got a sizzling heap, a full dozen, not of frogs' legs, as the menu described them, but of entire, crispy deep- fried frogs! In the photo, I've pulled one out of the pile. It's presented in dorsal view, with its ankles folded up behind the small of its back. They were dressed with parsley butter as promised and sided with a fat slice of lemon. Delicious! On the right, you can see what I had left when I finished with them. I ate as fast as I could, and David was very tolerant. The people at the next table had their dog with them (as did those opposite us), and at the end of their meal, they sent their plates back to the kitchen, where the scraps were gathered into a little covered doggy dish, which was brought back and set on the floor for their dog to finish up. The lady opposite us had brought her little white dog (a peekapoo maybe?) into the restaurant tucked under her arm like a rag doll and set it on an empty chair at their table, where it sat happily throughout the meal (they ordered specially for it, rather than feeding it their scraps; the waitress set the dish on the chair) until, at the end, she picked it up, tucked it under her arm, and carried it away with her. Its feet never touched the ground, and it seemed perfectly content with the arrangement. The two dogs, perhaps 10 feet apart the whole time, never showed the slightest interest in each other.

The Abbey of Cluny is difficult to photograph for the simple reason that it isn't there any more, but here are a couple of models to show what you're supposed to imagine. The one on the left shows the entire abbey complex, with part of the outer wall of the compound beyond. The one on the right shows only the abbey church and is designed for the blind. Out of the photo is an extensive braille explanation.

The Abbey of Cluny is difficult to photograph for the simple reason that it isn't there any more, but here are a couple of models to show what you're supposed to imagine. The one on the left shows the entire abbey complex, with part of the outer wall of the compound beyond. The one on the right shows only the abbey church and is designed for the blind. Out of the photo is an extensive braille explanation.

Today, the only parts that remain are the south arms of the large and small transcepts, part of the cloister, and parts of the square towers at the other end. The town has closed in around them, and a large hotel now covers part of the nave and other transcept arms, so even archeological investigations are difficult. In the early 20th century, an American named Kenneth J. Conant did extensive archeological work, and much of the "virtual" reconstruction is based on his data. The photo at the left shows an absolutely brilliant idea—it's a computerized viewing screen that swivels 360o on its post and can be tilted up and down, and whichever way you point it, it shows a reconstructed view of what you would be looking at if the church were still standing! It's apparently brand new and still a little flaky sometimes, but this is an idea that I'll bet will catch on with historical reconstructions the world over! The tour guide is holding up his notebook, with a floor plan of the church, to demonstrate which part of it we're looking at on the viewer. The other photo is a section of the outer compound wall that's still standing.

Today, the only parts that remain are the south arms of the large and small transcepts, part of the cloister, and parts of the square towers at the other end. The town has closed in around them, and a large hotel now covers part of the nave and other transcept arms, so even archeological investigations are difficult. In the early 20th century, an American named Kenneth J. Conant did extensive archeological work, and much of the "virtual" reconstruction is based on his data. The photo at the left shows an absolutely brilliant idea—it's a computerized viewing screen that swivels 360o on its post and can be tilted up and down, and whichever way you point it, it shows a reconstructed view of what you would be looking at if the church were still standing! It's apparently brand new and still a little flaky sometimes, but this is an idea that I'll bet will catch on with historical reconstructions the world over! The tour guide is holding up his notebook, with a floor plan of the church, to demonstrate which part of it we're looking at on the viewer. The other photo is a section of the outer compound wall that's still standing.

That worked, but before we came to anything we'd seen before we passed a bunch of other interesting stuff. For example, parts of the old monastery buildings now house the national school of "arts and metiers" (arts and occupations, shown at the left; I'm not sure just what constitutes an occupation, as opposed to a profession, but the students we passed seemed to be carrying architectural models; their "school uniform" is a long smock, almost like an academic gown, which they are free to decorate with all kinds of patches, pictures, writing, etc.). We also saw this war memorial inscribed "The victory of 1944 gives back to us hope and liberty." We even passed the Cluny branch of the national equestrian stud, which I had not realized existed. A sign on the gate offered guided tours, but this was about the third time we've discovered a national stud only after using up all the available time touring something else. Maybe next year . . .

That worked, but before we came to anything we'd seen before we passed a bunch of other interesting stuff. For example, parts of the old monastery buildings now house the national school of "arts and metiers" (arts and occupations, shown at the left; I'm not sure just what constitutes an occupation, as opposed to a profession, but the students we passed seemed to be carrying architectural models; their "school uniform" is a long smock, almost like an academic gown, which they are free to decorate with all kinds of patches, pictures, writing, etc.). We also saw this war memorial inscribed "The victory of 1944 gives back to us hope and liberty." We even passed the Cluny branch of the national equestrian stud, which I had not realized existed. A sign on the gate offered guided tours, but this was about the third time we've discovered a national stud only after using up all the available time touring something else. Maybe next year . . .

By that time, we were only half an hour early, so we just presented ourselves at the door as though everything were normal and my hair weren't sticking out in six directions and were ushered to our table without a murmur. We weren't even seriously underdressed. Once we had studied the choices and settled on the tasting menu (despite prices that were once again way higher than those in Beaune), I went to the ladies room, unbraided and fluffed my hair, then rebraided it, which helped a little. While I was gone, the first amuse-bouche arrived, and David, who, what with one thing and another, had been getting a little testy, cheered up and clowned around with my camera.

By that time, we were only half an hour early, so we just presented ourselves at the door as though everything were normal and my hair weren't sticking out in six directions and were ushered to our table without a murmur. We weren't even seriously underdressed. Once we had studied the choices and settled on the tasting menu (despite prices that were once again way higher than those in Beaune), I went to the ladies room, unbraided and fluffed my hair, then rebraided it, which helped a little. While I was gone, the first amuse-bouche arrived, and David, who, what with one thing and another, had been getting a little testy, cheered up and clowned around with my camera.

Second amuse-bouche: Cold purées of zucchini and of tomato with cream, topped with a savory tuile cooky with almond bits on it and sided by a croquette of cod-and-potato purée. Excellent.

Second amuse-bouche: Cold purées of zucchini and of tomato with cream, topped with a savory tuile cooky with almond bits on it and sided by a croquette of cod-and-potato purée. Excellent.

First course, both: Cold crab salad topped with a cold cooked shrimp and surrounded by cold asparagus gazpacho. We think the brownish arch with the neat round holes punched in it was a strip of dried rhubarb.

First course, both: Cold crab salad topped with a cold cooked shrimp and surrounded by cold asparagus gazpacho. We think the brownish arch with the neat round holes punched in it was a strip of dried rhubarb.

Third course, both: Lobster cooked in its shell with a lettuce cannelloni, wild asparagus, and "cardinal" sabayon (a fluffy, crustacean flavored hollandaise).

Third course, both: Lobster cooked in its shell with a lettuce cannelloni, wild asparagus, and "cardinal" sabayon (a fluffy, crustacean flavored hollandaise).

Fourth course, me: Sautéed veal sweetbreads with a sauce of roasted citrus peel, on a bed of chanterelles. On the side, a cylinder of potato that had been spiral-cut to let in the butter and the flavor of three kinds of pepper. All excellent.

Fourth course, me: Sautéed veal sweetbreads with a sauce of roasted citrus peel, on a bed of chanterelles. On the side, a cylinder of potato that had been spiral-cut to let in the butter and the flavor of three kinds of pepper. All excellent.