Tuesday, 23 June 2009, Encore et toujours Vauban!

Written 7 July 2009

Nice breakfast in this place. The young St. Nectaire cheese on the breakfast buffet for once lured me away from my usual bread, butter, and pastry. It may be the best approximation yet to the uninformatively named "fromage de vache" (cow's cheese) I had in a salad in St. Jean de Luz in 2006 and for which I've been in search of a substitute.

Step 1, as always, was a visit to the Office de Tourisme, where I photographed both this great promotional t-shirt and this very informative poster of the vinyards of the region. In approaching Chablis, we had finally broken out of the forest-and-pasture region of the Morvan and emerged into another wine-growing region—this one smallish, circumscribed, and centered on the town of Chablis, which sits in an elongated bowl, surrounded by vine-covered hillsides.

Step 1, as always, was a visit to the Office de Tourisme, where I photographed both this great promotional t-shirt and this very informative poster of the vinyards of the region. In approaching Chablis, we had finally broken out of the forest-and-pasture region of the Morvan and emerged into another wine-growing region—this one smallish, circumscribed, and centered on the town of Chablis, which sits in an elongated bowl, surrounded by vine-covered hillsides.

We were also able to sign up for a "vititour" for 10 a.m. the next morning and to obtain a brochure explaining where the snails come from! According to that brochure, almost nobody raises snails in Burgundy anymore, and the wild population can't support the demand, so the vast majority of "escargots de Bourgogne" (Helix pomatia L., by legal definition) are collected from the wild in central Europe and shipped to France already cooked.

Chablis vinyards (pretty much all Chardonnay) are also divided into four grades, called, from the top down, "grand cru," "premier cru," "chablis," and "petit chablis," and their distribution is more easily understood than that of the Côte d'Or (and here I draw on information we actually learned during our Wednesday morning vinyard tour)—all the "grands crus" of Chablis (just seven named parcels of land) are contiguous. You can see them on the map as the most darkly shaded region immediately northeast of the town. They are on the only hillsides that enjoy a full southern exposure. On all the other hills and ridges, the areas with (south)eastern exposure are the "premiers crus," those with the less favorable (north)western exposures are the "chablis," and those on the hilltops and plateaux (where the kimmeridgean soils give way to the less prized portlandian) are the "petits chablis." In outlying areas, like Irancy, they even make some red wines.

But the real business of the day was Bazoches, the trapezoidal château Vauban bought for himself in 1675 with a big cash bonus he got from Louis XIV (for knocking over some major fortress in the north of France; I forget which one). It was prominently mentioned at the Vauban museum, of course, and over the last day or two, we'd seen in advertised and read about it in the guidebook. Since we're here, we thought, we might as well do Vauban thoroughly. We had a day in hand, so we set off for Bazoches, almost due south of Chablis and even a ways beyond Vézelay, where we had stayed the Sunday night. That didn't involve retracing our steps, though, as we had some to Chablis by a round-about route, so we were traveling new and untrodden scenic country roads. Leaving Chablis, I was intrigued by a long series of single traffic cones, set by the side of the road, at intervals of a couple of kilometers, and always next to a short, straight line painted on the edge of the pavement. I never did figure out what they were about.

We got to the village of Bazoches (and could see the château on a hillside nearby) at lunchtime and followed the signs to La Grignotte (which means something like "the nibblery"), which looked quite promising. Unfortunately, once again, we found a deserted parking lot and an empty, dark restaurant on which hung a little sign saying "full up for lunch." Drat. And sure enough, by the time we got the car turned around to leave, the driveway and the road outside it were suddenly bumper to bumper with cars streaming into the parking lot, disgorging couples and small groups, all of an age and all mutually acquainted—the local golden-agers seemed to have booked the restuarant for their regular meeting. A drive through the rest of the town turned up the church where most of Vauban's body is buried (his heart in is a place of honor in Paris) but nowhere else to eat—not even a snack bar of last resort. So we started back toward Saint-Père (about 7 miles north), hoping to find something along the way, but we got there before we'd seen so much as a retail food store. Falling back on that row of restaurants at the foot of the hill, we settled on the least formal, Le Crécholien, an agreeable little place that offered salads.

Now I've looked it up since, and as far as I can tell, Créchol (from which a "Crécholien" would presumably come) is a little town in Auvergne, but the more we looked around, the less French the place seemed. The abstact art on the walls was certainly local (it had price tags on it), but the buffalo skull, peace pipe, feather headdress, and gods' eyes? And the menu—salad with roquefort dressing? ham and cheese muffin? (Sure, we've been served lots of little ham and cheese muffins on this trip, but they were always called something else.) I had the salad, and David ordered the muffin, which turned out also to be a salad, but topped with, sure enough, a large hot muffin-shaped object with lots of ham and cheese baked into it. Finally, we asked the hostess/waitress, who, it turned out, was also the proprietor, whether she was the fan of North American food and Indian art. Actually, she said, I'm from British Columbia. Aha! All was revealed. We switched into English and had a nice chat. She said that, ordinarily, all the art on the walls was American Indian, but this Dutch artist who spends half the year in in Vézelay had asked her to hang some of his work.

Now I've looked it up since, and as far as I can tell, Créchol (from which a "Crécholien" would presumably come) is a little town in Auvergne, but the more we looked around, the less French the place seemed. The abstact art on the walls was certainly local (it had price tags on it), but the buffalo skull, peace pipe, feather headdress, and gods' eyes? And the menu—salad with roquefort dressing? ham and cheese muffin? (Sure, we've been served lots of little ham and cheese muffins on this trip, but they were always called something else.) I had the salad, and David ordered the muffin, which turned out also to be a salad, but topped with, sure enough, a large hot muffin-shaped object with lots of ham and cheese baked into it. Finally, we asked the hostess/waitress, who, it turned out, was also the proprietor, whether she was the fan of North American food and Indian art. Actually, she said, I'm from British Columbia. Aha! All was revealed. We switched into English and had a nice chat. She said that, ordinarily, all the art on the walls was American Indian, but this Dutch artist who spends half the year in in Vézelay had asked her to hang some of his work.

The restroom included a twist on sanitary nicety that I had never encountered. The toilet-paper dispenser included a little sprayer that, if you stuck your paper under its electric eye, would spritz it with soothing antiseptic lotion.

Hunger pangs appeased (how can we be so hungry every day, after these huge dinners?!), we set off once again for Bazoches and, of course, got there before it reopened after the lunch break and had to wait around a few minues, admiring its mixed orchard (apples, plums, peaches, cherries, walnuts). Once inside, we found this interesting "lawn bastion" (here viewed from second-floor level; the railing is about knee high); it shows, in stylized form, the tradmark detached bastions that Vauban placed around his fortifications (tunnels connected them with the interior of the fortress). I have no idea whether Vauban chose that for his principal lawn ornament (it doesn't seem characteristic) or whether it was placed there later in commemoration.

Hunger pangs appeased (how can we be so hungry every day, after these huge dinners?!), we set off once again for Bazoches and, of course, got there before it reopened after the lunch break and had to wait around a few minues, admiring its mixed orchard (apples, plums, peaches, cherries, walnuts). Once inside, we found this interesting "lawn bastion" (here viewed from second-floor level; the railing is about knee high); it shows, in stylized form, the tradmark detached bastions that Vauban placed around his fortifications (tunnels connected them with the interior of the fortress). I have no idea whether Vauban chose that for his principal lawn ornament (it doesn't seem characteristic) or whether it was placed there later in commemoration.

This poster, photographed in the entrance hall, shows the château's trapezoidal shape (as well as the reflection of my hand and camera, in the lower right corner). The château's official website, at http://www.chateau-bazoches.com/accueil.htm, gives a better view, which also includes the old stable block, now the residence of the present owners. Also in the entrance hall was this reproduction of the famous "basterne," Vauban's mobile field office. The original has not survived; this one was built for a movie made about Vauban in 2007, the 300th anniversary of his death. I was curious, because the French always put "basterne" in quotation marks and make a point of saying that that's what Vauban called it, so I tried looking the word up. My dictionery gives as the first definition a sort of closed litter carried between two mules, but the first use dates from Vauban's lifetime, so I suspect that's where that definition comes from. The second definition is "Merovingian ox cart," and I suspect that's the original, which Vauban adopted with humorous intent.

This poster, photographed in the entrance hall, shows the château's trapezoidal shape (as well as the reflection of my hand and camera, in the lower right corner). The château's official website, at http://www.chateau-bazoches.com/accueil.htm, gives a better view, which also includes the old stable block, now the residence of the present owners. Also in the entrance hall was this reproduction of the famous "basterne," Vauban's mobile field office. The original has not survived; this one was built for a movie made about Vauban in 2007, the 300th anniversary of his death. I was curious, because the French always put "basterne" in quotation marks and make a point of saying that that's what Vauban called it, so I tried looking the word up. My dictionery gives as the first definition a sort of closed litter carried between two mules, but the first use dates from Vauban's lifetime, so I suspect that's where that definition comes from. The second definition is "Merovingian ox cart," and I suspect that's the original, which Vauban adopted with humorous intent.

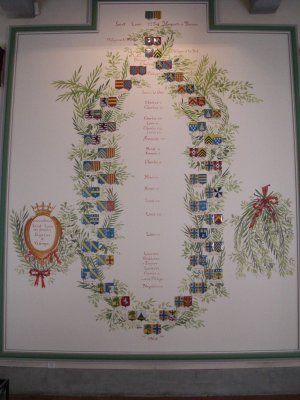

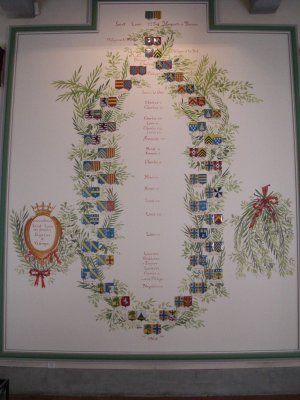

The tour of the house was self-guided, but we were provided with fat notebooks of information, in the language of our choice, explaining what there was to see. It pointed out the beautiful view from Vauban's private office of the church in Vézelay, silhouetted against the sky 7 miles away, the view in the other direction of the village of Bazoches in the valley below, the five-foot scale model of the Superbe, a French ship that sailed to the aid of the colonists during the American revolution, and the château's ballroom, which Vauban fitted up as the headquarters for his engineering staff. I was hoping it had been furnished to reflect that use, but instead it serves as a kind of museum. (That's where you can see Vauban's famous armor breastplate, pocked with bullet dents.) On the walls are four huge family trees, showing the descent of the various owners of the château. The position of each individual is marked by a custom-made, hand-painted tile depicting his or her family coat of arms. (Apparently, to the practiced and knowledgeable eye, that makes the trees easier to parse and lineages easier to trace through them.) The one shown at the left is a special diagram showing how the marriage of the current occupants of the château reunited (after 20 generations or so) the two principal branches of the family that originally built the place and (if I understood the explanations correctly) Vauban's family as well (down the center are the names of the kings and emporers of France who came and went while the two branches were sundered). The marriage shown on the right, from one of the other family trees, shows the wonderfully whimsical coat of arms of Regis de Montgolfier, who married into the family at some point (the trees are maddenly devoid of dates); his ancestors invented the hot-air balloon.

The tour of the house was self-guided, but we were provided with fat notebooks of information, in the language of our choice, explaining what there was to see. It pointed out the beautiful view from Vauban's private office of the church in Vézelay, silhouetted against the sky 7 miles away, the view in the other direction of the village of Bazoches in the valley below, the five-foot scale model of the Superbe, a French ship that sailed to the aid of the colonists during the American revolution, and the château's ballroom, which Vauban fitted up as the headquarters for his engineering staff. I was hoping it had been furnished to reflect that use, but instead it serves as a kind of museum. (That's where you can see Vauban's famous armor breastplate, pocked with bullet dents.) On the walls are four huge family trees, showing the descent of the various owners of the château. The position of each individual is marked by a custom-made, hand-painted tile depicting his or her family coat of arms. (Apparently, to the practiced and knowledgeable eye, that makes the trees easier to parse and lineages easier to trace through them.) The one shown at the left is a special diagram showing how the marriage of the current occupants of the château reunited (after 20 generations or so) the two principal branches of the family that originally built the place and (if I understood the explanations correctly) Vauban's family as well (down the center are the names of the kings and emporers of France who came and went while the two branches were sundered). The marriage shown on the right, from one of the other family trees, shows the wonderfully whimsical coat of arms of Regis de Montgolfier, who married into the family at some point (the trees are maddenly devoid of dates); his ancestors invented the hot-air balloon.

The information notebook also revealed that the château was built on the site of an older Roman fortification. Just a few miles away, between Bazoches and Vézelay, are some warm salt springs (currently the site of archeological excavations) where the Romans built baths, and only 40 m from the château passes the old Roman road from Sens to Autun. We didn't have the time to visit either.

On the grounds were a magnificent spruce and plane tree that could conceivably date from Vauban's time, though they were not marked or dated. Just outside the gates was a large tree with shreddy red bark and cypress-like leaves that I'm pretty sure was a redwood of some sort. The current driveway takes a different route, but you can still see the original horse-and-carriage approach to the house, marked by a double allée of trees, now just crossing a meadow from the main road up to the house.

We took a different route back to Chablis, partly for the sight-seeing and partly because we needed gas, and the nearest filling station marked on our Michelin map lay west of Bazoches, on the way to Clamecy. To our dismay, though, it turned out to be prominently labeled "24 h self service," which is code for "unmanned." As has proved the case in the past at such establishments, we were out of luck, because the pumps accept only European credit cards with chips, and we're still stuck with our good old mag-strip Visa. So we pressed on into Clamecy, where two additional little blue gas pumps appeared on the map, and followed the signs through a tangle of one-ways to a huge LeClerc supermarket on the far side of the town, where, as we had hoped, you had the option of paying, in cash or with an American credit card, the person in the little booth at the exit. We even managed to find our way back out of Clamecy and onto the scenic route back to Chablis.

Our route took us, for a long stretch along the banks of the Canal du Nivernais, the oldest in France. It, besides being darn scenic, was much more heavily populated with pleasure boats. The most popular were cabin-cruiser types that probably slept four, but we saw a few of what had to be "penichettes," narrow boats shaped like canal barges ("peniches") but shortened, and one actual hotel barge. We happened on the heavily advertised "Cardoland," which seems to be a sort of dinosaur-and-prehistory theme park located in the somehow appropriately named village of Chamoux (pronounced "Shamu"). As we approached Chablis from the southwest, we passed through the Irancy region, which lived up to double reputation for cherries and a pleasant red wine. Roadside stands all along the way were selling the cherries, and many restaurants just now are offering desserts based on cherries cooked in Irancy wine.

Written 9 July

We had dinner in the hotel again, this time ordering the big tasting menu.

First amuse-bouche: Same as the night before

Second amuse-bouche: A small glass of excellent hot mushroom soup.

Second amuse-bouche: A small glass of excellent hot mushroom soup.

First course: Cold sliced foie gras of duck, garnished with both ficoïide glacier and a sprig of purslane (Portulaca oleracea) and laid on top of a warm "salad" of chanterelles tossed with argan oil (i.e., oil from the nuts of the Argania spinosa, Sapotaceae). Very good, but I didn't notice anything in particular about the argan oil.

Second course: Roasted langoustine (Nephrops norvegicus) tails on a bed of sautéed spinach and sorrel, with a roasted cherry tomato and roasted hazelnut oil. David felt that the sorrel had overpowered yesterday's fish and preferred this version, cut with milder spinach.

Second course: Roasted langoustine (Nephrops norvegicus) tails on a bed of sautéed spinach and sorrel, with a roasted cherry tomato and roasted hazelnut oil. David felt that the sorrel had overpowered yesterday's fish and preferred this version, cut with milder spinach.

Third course: Sautéed filet of brill (Scopthalmus rhombus, a flatfish) with arenka butter and stewed baby leeks. Arenka is apparently a newfangled immitation caviare made of herring (and not involving herring eggs)., and sure enough, the butter sauce had little black caviare-like things floating in it. The purplish object is a radish, stewed with the leeks and other vegetables.

Fourth course: Filet mignon of veal roasted with bacon on a bed of oyster mushrooms with veal-Chablis-wine sauce. On the side, of all things, potato chips—delicious, fragile, house-made potato chips. This veal put all the other sautéed and roasted veals of the trip seriously in the shade. It was outstanding! The waiter explained that it was cooked for 12 hours at 50°C, under vacuum—good luck duplicating that at home. (I've since done some research, and the modern version of "under vacuum," at least in cooking, is vacuum packed in a plastic pouch. They brown the meat first, then seal it in one of those heavy plastic "cryovac" pouches, then leave it for 12 hours in a 50°C water bath. It can then be served immediately or refrigerated, still its vacuum pack, then gently reheated in warm water. Either way, it comes out rare, juicy, and amazingly tender, but where am I going to get a 50°C water bath? Maybe a state surplus auction.)

Fourth course: Filet mignon of veal roasted with bacon on a bed of oyster mushrooms with veal-Chablis-wine sauce. On the side, of all things, potato chips—delicious, fragile, house-made potato chips. This veal put all the other sautéed and roasted veals of the trip seriously in the shade. It was outstanding! The waiter explained that it was cooked for 12 hours at 50°C, under vacuum—good luck duplicating that at home. (I've since done some research, and the modern version of "under vacuum," at least in cooking, is vacuum packed in a plastic pouch. They brown the meat first, then seal it in one of those heavy plastic "cryovac" pouches, then leave it for 12 hours in a 50°C water bath. It can then be served immediately or refrigerated, still its vacuum pack, then gently reheated in warm water. Either way, it comes out rare, juicy, and amazingly tender, but where am I going to get a 50°C water bath? Maybe a state surplus auction.)

Palate cleanser: The same cold mint tea with the lime ice cube.

Cheese: Nothing very new or different. For David, Pierre-qui-vire and Brillat-Savarin. For me, Chaource, mustard-coated Delice de Pommard, and Selle-sur-Cher (another rather dry chevre). I had had the Delice de Pommard before—it's a soft, fresh goat cheese rolled in mustard bran—and found it quite mild. This one was so mustardy I couldn't eat it.

Dessert: A cold soup of fresh Irancy cherries poached in Irancy red wine, served with a sweet tarragon sorbet. Also excellent.

Dessert: A cold soup of fresh Irancy cherries poached in Irancy red wine, served with a sweet tarragon sorbet. Also excellent.

The mignardises were the same as those of the night before except that the almond macaroons had been replaced with coconut ones.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Step 1, as always, was a visit to the Office de Tourisme, where I photographed both this great promotional t-shirt and this very informative poster of the vinyards of the region. In approaching Chablis, we had finally broken out of the forest-and-pasture region of the Morvan and emerged into another wine-growing region—this one smallish, circumscribed, and centered on the town of Chablis, which sits in an elongated bowl, surrounded by vine-covered hillsides.

Step 1, as always, was a visit to the Office de Tourisme, where I photographed both this great promotional t-shirt and this very informative poster of the vinyards of the region. In approaching Chablis, we had finally broken out of the forest-and-pasture region of the Morvan and emerged into another wine-growing region—this one smallish, circumscribed, and centered on the town of Chablis, which sits in an elongated bowl, surrounded by vine-covered hillsides.

Now I've looked it up since, and as far as I can tell, Créchol (from which a "Crécholien" would presumably come) is a little town in Auvergne, but the more we looked around, the less French the place seemed. The abstact art on the walls was certainly local (it had price tags on it), but the buffalo skull, peace pipe, feather headdress, and gods' eyes? And the menu—salad with roquefort dressing? ham and cheese muffin? (Sure, we've been served lots of little ham and cheese muffins on this trip, but they were always called something else.) I had the salad, and David ordered the muffin, which turned out also to be a salad, but topped with, sure enough, a large hot muffin-shaped object with lots of ham and cheese baked into it. Finally, we asked the hostess/waitress, who, it turned out, was also the proprietor, whether she was the fan of North American food and Indian art. Actually, she said, I'm from British Columbia. Aha! All was revealed. We switched into English and had a nice chat. She said that, ordinarily, all the art on the walls was American Indian, but this Dutch artist who spends half the year in in Vézelay had asked her to hang some of his work.

Now I've looked it up since, and as far as I can tell, Créchol (from which a "Crécholien" would presumably come) is a little town in Auvergne, but the more we looked around, the less French the place seemed. The abstact art on the walls was certainly local (it had price tags on it), but the buffalo skull, peace pipe, feather headdress, and gods' eyes? And the menu—salad with roquefort dressing? ham and cheese muffin? (Sure, we've been served lots of little ham and cheese muffins on this trip, but they were always called something else.) I had the salad, and David ordered the muffin, which turned out also to be a salad, but topped with, sure enough, a large hot muffin-shaped object with lots of ham and cheese baked into it. Finally, we asked the hostess/waitress, who, it turned out, was also the proprietor, whether she was the fan of North American food and Indian art. Actually, she said, I'm from British Columbia. Aha! All was revealed. We switched into English and had a nice chat. She said that, ordinarily, all the art on the walls was American Indian, but this Dutch artist who spends half the year in in Vézelay had asked her to hang some of his work.

Hunger pangs appeased (how can we be so hungry every day, after these huge dinners?!), we set off once again for Bazoches and, of course, got there before it reopened after the lunch break and had to wait around a few minues, admiring its mixed orchard (apples, plums, peaches, cherries, walnuts). Once inside, we found this interesting "lawn bastion" (here viewed from second-floor level; the railing is about knee high); it shows, in stylized form, the tradmark detached bastions that Vauban placed around his fortifications (tunnels connected them with the interior of the fortress). I have no idea whether Vauban chose that for his principal lawn ornament (it doesn't seem characteristic) or whether it was placed there later in commemoration.

Hunger pangs appeased (how can we be so hungry every day, after these huge dinners?!), we set off once again for Bazoches and, of course, got there before it reopened after the lunch break and had to wait around a few minues, admiring its mixed orchard (apples, plums, peaches, cherries, walnuts). Once inside, we found this interesting "lawn bastion" (here viewed from second-floor level; the railing is about knee high); it shows, in stylized form, the tradmark detached bastions that Vauban placed around his fortifications (tunnels connected them with the interior of the fortress). I have no idea whether Vauban chose that for his principal lawn ornament (it doesn't seem characteristic) or whether it was placed there later in commemoration.

This poster, photographed in the entrance hall, shows the château's trapezoidal shape (as well as the reflection of my hand and camera, in the lower right corner). The château's official website, at

This poster, photographed in the entrance hall, shows the château's trapezoidal shape (as well as the reflection of my hand and camera, in the lower right corner). The château's official website, at

The tour of the house was self-guided, but we were provided with fat notebooks of information, in the language of our choice, explaining what there was to see. It pointed out the beautiful view from Vauban's private office of the church in Vézelay, silhouetted against the sky 7 miles away, the view in the other direction of the village of Bazoches in the valley below, the five-foot scale model of the Superbe, a French ship that sailed to the aid of the colonists during the American revolution, and the château's ballroom, which Vauban fitted up as the headquarters for his engineering staff. I was hoping it had been furnished to reflect that use, but instead it serves as a kind of museum. (That's where you can see Vauban's famous armor breastplate, pocked with bullet dents.) On the walls are four huge family trees, showing the descent of the various owners of the château. The position of each individual is marked by a custom-made, hand-painted tile depicting his or her family coat of arms. (Apparently, to the practiced and knowledgeable eye, that makes the trees easier to parse and lineages easier to trace through them.) The one shown at the left is a special diagram showing how the marriage of the current occupants of the château reunited (after 20 generations or so) the two principal branches of the family that originally built the place and (if I understood the explanations correctly) Vauban's family as well (down the center are the names of the kings and emporers of France who came and went while the two branches were sundered). The marriage shown on the right, from one of the other family trees, shows the wonderfully whimsical coat of arms of Regis de Montgolfier, who married into the family at some point (the trees are maddenly devoid of dates); his ancestors invented the hot-air balloon.

The tour of the house was self-guided, but we were provided with fat notebooks of information, in the language of our choice, explaining what there was to see. It pointed out the beautiful view from Vauban's private office of the church in Vézelay, silhouetted against the sky 7 miles away, the view in the other direction of the village of Bazoches in the valley below, the five-foot scale model of the Superbe, a French ship that sailed to the aid of the colonists during the American revolution, and the château's ballroom, which Vauban fitted up as the headquarters for his engineering staff. I was hoping it had been furnished to reflect that use, but instead it serves as a kind of museum. (That's where you can see Vauban's famous armor breastplate, pocked with bullet dents.) On the walls are four huge family trees, showing the descent of the various owners of the château. The position of each individual is marked by a custom-made, hand-painted tile depicting his or her family coat of arms. (Apparently, to the practiced and knowledgeable eye, that makes the trees easier to parse and lineages easier to trace through them.) The one shown at the left is a special diagram showing how the marriage of the current occupants of the château reunited (after 20 generations or so) the two principal branches of the family that originally built the place and (if I understood the explanations correctly) Vauban's family as well (down the center are the names of the kings and emporers of France who came and went while the two branches were sundered). The marriage shown on the right, from one of the other family trees, shows the wonderfully whimsical coat of arms of Regis de Montgolfier, who married into the family at some point (the trees are maddenly devoid of dates); his ancestors invented the hot-air balloon.

Second amuse-bouche: A small glass of excellent hot mushroom soup.

Second amuse-bouche: A small glass of excellent hot mushroom soup.

Second course: Roasted langoustine (Nephrops norvegicus) tails on a bed of sautéed spinach and sorrel, with a roasted cherry tomato and roasted hazelnut oil. David felt that the sorrel had overpowered yesterday's fish and preferred this version, cut with milder spinach.

Second course: Roasted langoustine (Nephrops norvegicus) tails on a bed of sautéed spinach and sorrel, with a roasted cherry tomato and roasted hazelnut oil. David felt that the sorrel had overpowered yesterday's fish and preferred this version, cut with milder spinach. Fourth course: Filet mignon of veal roasted with bacon on a bed of oyster mushrooms with veal-Chablis-wine sauce. On the side, of all things, potato chips—delicious, fragile, house-made potato chips. This veal put all the other sautéed and roasted veals of the trip seriously in the shade. It was outstanding! The waiter explained that it was cooked for 12 hours at 50°C, under vacuum—good luck duplicating that at home. (I've since done some research, and the modern version of "under vacuum," at least in cooking, is vacuum packed in a plastic pouch. They brown the meat first, then seal it in one of those heavy plastic "cryovac" pouches, then leave it for 12 hours in a 50°C water bath. It can then be served immediately or refrigerated, still its vacuum pack, then gently reheated in warm water. Either way, it comes out rare, juicy, and amazingly tender, but where am I going to get a 50°C water bath? Maybe a state surplus auction.)

Fourth course: Filet mignon of veal roasted with bacon on a bed of oyster mushrooms with veal-Chablis-wine sauce. On the side, of all things, potato chips—delicious, fragile, house-made potato chips. This veal put all the other sautéed and roasted veals of the trip seriously in the shade. It was outstanding! The waiter explained that it was cooked for 12 hours at 50°C, under vacuum—good luck duplicating that at home. (I've since done some research, and the modern version of "under vacuum," at least in cooking, is vacuum packed in a plastic pouch. They brown the meat first, then seal it in one of those heavy plastic "cryovac" pouches, then leave it for 12 hours in a 50°C water bath. It can then be served immediately or refrigerated, still its vacuum pack, then gently reheated in warm water. Either way, it comes out rare, juicy, and amazingly tender, but where am I going to get a 50°C water bath? Maybe a state surplus auction.)  Dessert: A cold soup of fresh Irancy cherries poached in Irancy red wine, served with a sweet tarragon sorbet. Also excellent.

Dessert: A cold soup of fresh Irancy cherries poached in Irancy red wine, served with a sweet tarragon sorbet. Also excellent.