Wednesday, 24 June 2009, Chablis to Joigny

Written 9 July 2009

Yes, on Wednesday, we were to drive from from Chablis to Joigny, but nobody every accused us of taking the shortest route between two points in France. First, of course, we had our 90-minute "Vititour" scheduled for 10 a.m. After that, we wanted to take in Ancy-le-Franc castle on the way to Joigny—even though Chablis to Ancy was about as far as Chablis to Joigny, and in exactly the opposite direction.

Yes, on Wednesday, we were to drive from from Chablis to Joigny, but nobody every accused us of taking the shortest route between two points in France. First, of course, we had our 90-minute "Vititour" scheduled for 10 a.m. After that, we wanted to take in Ancy-le-Franc castle on the way to Joigny—even though Chablis to Ancy was about as far as Chablis to Joigny, and in exactly the opposite direction.

After another pleasant breakfast of raw ham, pastries, and St. Nectaire at this handsome buffet (coffee, chocolate, cereal, fresh and dried fruit, and a couple of flavors of pound cake are out of sight on the other side), we strolled down in plenty of time to meet our tour guide at the Office de Tourisme. (On the way, we passed the Laroche wine bar, where the advertised lunch special was a "terre et mer" (surf and turf) sandwich—pig's foot and fresh sardine.) The guide was early, too, and we were the only clients to sign up, so we got a good start.

Franck, our guide, said that the day before he'd had an entire van-load of eight Norwegians, so he'd had to do the tour in English, which is much more stressful, so he was glad we preferred French. He started by driving us northeast out of town and straight up the side of the hill, right through the grands crus, on a steep and narrow gravel track that enjoys the name "Voie meurtrière," the murderous way. These days, it's not so bad, at least in good weather, but over the centuries, a great number of horses, and not a few people, have come to grief trying to get loaded wagons up and down it. Even now, he says, motor vehicles have trouble when it's wet or icy.

At the top, at the boundary between the trees and the vines, was this orientation table, on which Franck pointed out the locations and exposures of the four grades of vinyard—grand cru, premier cru, Chablis, and petit Chablis. Those vines directly in front of us are in the grand cru area, the Les Grenouilles sector, I think. He also showed us this chunk of Chablis subsoil, and "soil" is used rather loosely here—it was basically a piece of rock. Note all the little seashells embedded in it—those are Ostrea virgula, little comma-shaped Jurassic oysters characteristic of the Kimmeridgean soils that give Chablis wines their very mineral character. Their keeping qualities, much better than most whites, are also chalked up (as it were) to their mineral content. On tops of the ridges and on plateaus, the Kimmeridgean soils are covered by Portlandian ones, so those areas are only "petit Chablis. He reminisced about a recent vintage year in which the weather was completely haywire. "It was strange," he said, "you'd think we were living in Meursault instead of Chablis! We didn't really make Chablis that year; we made Meursault. It didn't keep worth a darn, but it was really good!"

At the top, at the boundary between the trees and the vines, was this orientation table, on which Franck pointed out the locations and exposures of the four grades of vinyard—grand cru, premier cru, Chablis, and petit Chablis. Those vines directly in front of us are in the grand cru area, the Les Grenouilles sector, I think. He also showed us this chunk of Chablis subsoil, and "soil" is used rather loosely here—it was basically a piece of rock. Note all the little seashells embedded in it—those are Ostrea virgula, little comma-shaped Jurassic oysters characteristic of the Kimmeridgean soils that give Chablis wines their very mineral character. Their keeping qualities, much better than most whites, are also chalked up (as it were) to their mineral content. On tops of the ridges and on plateaus, the Kimmeridgean soils are covered by Portlandian ones, so those areas are only "petit Chablis. He reminisced about a recent vintage year in which the weather was completely haywire. "It was strange," he said, "you'd think we were living in Meursault instead of Chablis! We didn't really make Chablis that year; we made Meursault. It didn't keep worth a darn, but it was really good!"

From there, we drove back down the hill, around the town, and back up the hill on the other side, to a clearing at the top edge of the vines. On the way, Franck gave us some statistics. Burgundy as a whole harbors 101 appellations controlées (legally protected named points of origin), only 30 or so of which are grands crus. Around Chablis are 4700 ha of the "chablis" grade but only 100 ha of grands crus, all contiguous in a one 1-km stretch along the D65. Chablis produces about 20 million bottles of wine a year, 80% of which are exported. Only about 10% of Chablis is matured in oak; the rest, of grades that would not benefit from the process or wouldn't command a price that would justify the expense, are matured in stainless steel. The grapes are harvested, as a rule of thumb, 100 days after the vines flower (the vines are obligate selfers; no pollinator needed). In the photo on the left, we're looking across the valley (with the town of Chablis in the bottom) at the hillside of grands crus on the other side. The largest white roof in the town is the coop, for small or beginning growers not ready to go independent yet. (As we drove back through town later, Franck pointed out, in order as we passed them, the elementary school, the secondary school, and the coop. "A natural progression, as we like to say around here.")

From there, we drove back down the hill, around the town, and back up the hill on the other side, to a clearing at the top edge of the vines. On the way, Franck gave us some statistics. Burgundy as a whole harbors 101 appellations controlées (legally protected named points of origin), only 30 or so of which are grands crus. Around Chablis are 4700 ha of the "chablis" grade but only 100 ha of grands crus, all contiguous in a one 1-km stretch along the D65. Chablis produces about 20 million bottles of wine a year, 80% of which are exported. Only about 10% of Chablis is matured in oak; the rest, of grades that would not benefit from the process or wouldn't command a price that would justify the expense, are matured in stainless steel. The grapes are harvested, as a rule of thumb, 100 days after the vines flower (the vines are obligate selfers; no pollinator needed). In the photo on the left, we're looking across the valley (with the town of Chablis in the bottom) at the hillside of grands crus on the other side. The largest white roof in the town is the coop, for small or beginning growers not ready to go independent yet. (As we drove back through town later, Franck pointed out, in order as we passed them, the elementary school, the secondary school, and the coop. "A natural progression, as we like to say around here.")

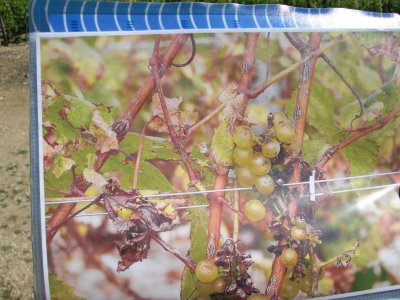

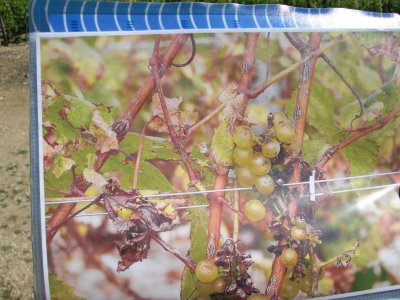

In the photo on the right (above), he points out to us the shoot that he would choose to initiate next year's growth. In the winter, he's a vine pruner by trade. An experienced worker like him can prune about a hectare of vines in a month, choosing a single shoot to preserve, triming to to 6-8 buds, pruning away all the other growth, then bending the single shoot down along the trellis wire and tying it in place. The photo to the right here is of a page in his notebook of illustrations, showing hail damage. I asked him about the "Hailed vine is a smoked vine" proverb—what is a "smoked vine"? He'd never heard the expression, but he assured us that hail is the winemaker's greatest fear, that a hailed vine is a severely damaged vine. As the photo shows, almost all the grapes were pierced by hailstone strikes and therefore either dried up or rotted, and the stems are covered with scars where the hailstones broke or bruised the tender bark earlier in the season. No matter what shoot the pruner chooses to preserve, those scars will make it brittle, and when he tries to bend it to the trellis, it will inevitably break off short, leaving only one or two buds to grow in the coming season.

In the photo on the right (above), he points out to us the shoot that he would choose to initiate next year's growth. In the winter, he's a vine pruner by trade. An experienced worker like him can prune about a hectare of vines in a month, choosing a single shoot to preserve, triming to to 6-8 buds, pruning away all the other growth, then bending the single shoot down along the trellis wire and tying it in place. The photo to the right here is of a page in his notebook of illustrations, showing hail damage. I asked him about the "Hailed vine is a smoked vine" proverb—what is a "smoked vine"? He'd never heard the expression, but he assured us that hail is the winemaker's greatest fear, that a hailed vine is a severely damaged vine. As the photo shows, almost all the grapes were pierced by hailstone strikes and therefore either dried up or rotted, and the stems are covered with scars where the hailstones broke or bruised the tender bark earlier in the season. No matter what shoot the pruner chooses to preserve, those scars will make it brittle, and when he tries to bend it to the trellis, it will inevitably break off short, leaving only one or two buds to grow in the coming season.

Hail is not the only danger. Late freezes can also wipe out the whole year's crop, so the most valuable tracts of vines are protected by one of three methods. One is huge candles (the equivalent of the smudgepots of citrus groves). Some hundreds per hectare are deployed in the vinyards, and when frost threatens, the growers rush out to light them. Another is electrical heating elements, strung along the trellises, designed to keep the vines warm. Third is "aspersion"—spraying the vines with water, just as citrus growers spray their orange trees. Apparently, a vine can tolerate 0°C just fine, but -1 or -2°C can be disastrous if it lasts a few hours, so a coating of ice, which keeps the temperature exactly at zero, is good protection. He asked whether we had see the large reservoir in nearby Beine, and its huge pumping station (we had, on our way back from Bazoches); after three freezing nights, he said, that reservoir is sometimes empty.

Finally, as the tour drew to a close, Franck opened up the back of his van and produced, a little folding table, two glasses, and a half bottle of wine made by a family who've been making wine for 13 generations. A very good tour. Just Google "Chablis Vititours" to see Franck's website.

Finally, as the tour drew to a close, Franck opened up the back of his van and produced, a little folding table, two glasses, and a half bottle of wine made by a family who've been making wine for 13 generations. A very good tour. Just Google "Chablis Vititours" to see Franck's website.

David had told me (he learns the most amazing things from listening to Champs Elysées) that the Chablis area had been in serious decline until recently, when a particular winemaker started a major campaign to bring it back to prominence, but I had realized how bad the problem had been until Franck also explained it. In th late 19th century, Phylloxera wiped out the vinyards of Chablis, as it did those of most French wine-growing regions, but then almost immediately afterward, before they could recover, Chablis lost an inordinate number of its young men in World War II—so many that no one was left to tend the vines. The female population tried to keep the businesses going, but most had to abandon wine making altogether. Only in the 1980's did hte concerted PR effort begin to turn things around. The area certainly seems to be prospering now, at least to the extent anyone is in today's economy.

Written 10 July 2009

Back at Hostellerie des Clos, we bid farefwell to the single goldfish, in a handsome glass bowl with a few black stones in the bottom, that graces the lobby, packed up the car, and headed for Ancy le Franc. We got there at lunchtime and began the usual search for a suitable eatery. Eventually, we followed the signs several kilometers out of town, along the canal, to lock #79, where sat overlooking the canal at a little hotel-restaurant called, appropriately enough, L'Écluse, "the lock." No actual boats cruised by while we were there, but foot and bicycle traffic on the towpath on the opposite bank was endlessly entertaining. One couple toodled by on a bicycle built for two on which the front seat was recumbant and the rear seat upright. They were packing goodsized saddlebags and might actually have been travelling somewhere.

Back at Hostellerie des Clos, we bid farefwell to the single goldfish, in a handsome glass bowl with a few black stones in the bottom, that graces the lobby, packed up the car, and headed for Ancy le Franc. We got there at lunchtime and began the usual search for a suitable eatery. Eventually, we followed the signs several kilometers out of town, along the canal, to lock #79, where sat overlooking the canal at a little hotel-restaurant called, appropriately enough, L'Écluse, "the lock." No actual boats cruised by while we were there, but foot and bicycle traffic on the towpath on the opposite bank was endlessly entertaining. One couple toodled by on a bicycle built for two on which the front seat was recumbant and the rear seat upright. They were packing goodsized saddlebags and might actually have been travelling somewhere.

David had a salad topped with goat cheese on large croutons and a drift of outstandingly tasty toasted pine nuts. I ordered the "salade façon tartiflette"—wasn't that some sort of ham and cheese pie? Sure enough, my salad came topped with a large serving (only a fraction of which shows in the photo)of tartiflette, a layer of thick cooked-potato slices liberally topped with lardons, then a thick layer of reblochon cheese and run under the broiler. Yum! I had always assumed tartiflette was a traditional dish, but it turns out to have been invented and promoted in the 1980's by (who else?) the makers of reblochon.

David had a salad topped with goat cheese on large croutons and a drift of outstandingly tasty toasted pine nuts. I ordered the "salade façon tartiflette"—wasn't that some sort of ham and cheese pie? Sure enough, my salad came topped with a large serving (only a fraction of which shows in the photo)of tartiflette, a layer of thick cooked-potato slices liberally topped with lardons, then a thick layer of reblochon cheese and run under the broiler. Yum! I had always assumed tartiflette was a traditional dish, but it turns out to have been invented and promoted in the 1980's by (who else?) the makers of reblochon.

Ancy-le-Franc was built between 1542 and 1550 from plans by Sebastiano Serlio and is resolutely Renaissance and resolutely symmetrical. Serlio liked symmetry, and he liked what he called "rhythm" in the alternation of masses and voids along a surface, so we found nothing trapezoidal, unfinished, or haphazard here. On the left is one facade of the château (all four sides are similar, of course) and on the right the stable block, not included in the tour.

Ancy-le-Franc was built between 1542 and 1550 from plans by Sebastiano Serlio and is resolutely Renaissance and resolutely symmetrical. Serlio liked symmetry, and he liked what he called "rhythm" in the alternation of masses and voids along a surface, so we found nothing trapezoidal, unfinished, or haphazard here. On the left is one facade of the château (all four sides are similar, of course) and on the right the stable block, not included in the tour.

In 1683, it was purchased by the Marquis de Louvois, Louis XIV's war minister, and a major rival of Vauban's. The two men were as different as their châteaux—Louvois was an aristocrat and proud of it, profoundly resentful that a nobody like Vauban could rise to rank almost the equal of his. He hung around the court, which Vauban could never be bothered to do, and the two of them were often at odds in the advice they offered the king. The château is now owned by a corporation that buys and restores historical buildings; only guided tours are permitted.

Again, no photos were allowed inside. The tour started with an explanation of the Ancy coat of arms, which includes three elements expressly granted by the pope (I forget which one, but one of those that found himself challenged by rival popes—the proprietor of Ancy was instrumental is helping him regain his thrown): the keys of St. Peter, a papal crown, and the motto "Si omnes ego non" ("If everyone [else has abandoned you] not I"). From there we went into the chapel, which is lovely in itself but is most famous for its three hidden doors. One opens into a sacristy the size of a small walk-in closet, one into a tiny mortuary chapel with a window into the main chapel, and one into a room in which funerary mementos are stored.

In another room was a magnificent six-foot tall cabinet with many doors and drawers, all encrusted with minutely carved and sheets of bone and ivory. It was all made by a single artist, and it took him 35 years! In a larger room was a huge painting of a raging battle among men on horseback. As the guide pointed out, one should look at the eyes. The men's eyes are all filled with blood-thirsty ferocity; those of the horses with horror and dismay. Just who, the artist seems to ask, are the beasts here?

From Ancy, we set off for Joigny, but rather than retrace our steps past Chablis, we took a different route, along the river Armençon. The Armençon flows westward and the Yonne eastward until, at Migennes, they collide head on and flow away south (as the Yonne) toward Auxerre. I looked for the confluence, but buildings were in the way, so we simply drove into Migennes downstream along the Armençon and left it driving upstream along the Yonne.

At one point (on the way to Ancy, I think) we passed one of those "you think you've got problems" situations—driving through open countryside, we came zooming over a hill at the local speed limit (110 km/hr) and had to swerve to avoid colliding with a huge semi truck, stopped in front of an overpass that his load was clearly at least 18 inches too tall to fit under. Good thing nobody was coming the other way. And good luck to that driver trying to do a three-point turn, in a truck that size, on two-lane blacktop, without getting hit by somebody coming over the hill!

At another, we came to a level crossing. No train was in sight, but the barriers were down and the lights flashing, so we obediently stopped. A little sign indicated a "subterranean passage" off to one side, which we assumed was for pedestrians, but a car coming the other way drove through it, so it must be allowed (or at least tolerated). We turned down the ramp, drove through a little tunnel just tall and wide enough for one car, and climbed back up the ramp on the other side to continue on our way. We never did see the train.

In Joigny, which is divided by the Yonne, our hotel and our restaurant for the night faced each other across the river, both a few hundred meters west of the bridge. I had a good area map that showed just how to get there—drive into town from the east on the D943, along the north bank of the river; take a left over the bridge; then take an immediate right on the tiny road along the south bank, then left into the hotel's parking lot. But as we arrived at the south end of the bridge, I saw the little sign: "Aargh, no right turn; go straight!" Okay, no biggie; at this big rotary coming up, we'll take a right and circle around to come in from the other direction. But when we got there, the road was barricaded, just short of the turn we needed. Drat. Okay, I said, let's go back over the bridge, turn right, drive the few blocks to our restaurant and call the hotel from there, asking how the heck we get to them. David didn't want to go back through that rotary, which had turned out to be only a semirotary, dissolving on one side into a hairy tangle of one-ways, stop lights, and protected turns (and it was rush hour), but I convinced him we had to go back— no other roads gave access to our hotel's area, and no other bridge crossed the river for 20 km on either side! So we did, tried a couple of left turns that might go through to the hotel but didn't (each entailing a left turn off the busy bridge approach and then another back onto it) and were finally forced back over the bridge to the north bank. Okay, before calling, let's try one more pass, in case I misread the no-right-turn sign; as we watched from the north bank, cars were clearly turning right down that road. Once more over the bridge, yes, I saw my error—the little black "truck" icon below the no-turn arrow, meaning "no right turn if you weigh over 3.5 tons." From there, of course, it was a piece of cake. David (who had been driving for a long time at this point) was pretty annoyed at the do-si-do, though; I admit that, on the fly, I often overlook the little truck symbol, sending us off on detours when cars were allowed to go straight; I also mix up the "no entry" and "no parking" symbols (which one is white and which blue?)

Our hotel, La Rive Gauche (the Left Bank), showed signs of recent renovation from some other use, and all the plantings were quite young (although it's been in the guidebooks for at least five years). We were puzzled by the large "LB" monograms in the wrought-iron gates, carpets, etc., until we realized that, until recently, it had probably been called "The Left Bank." We noticed that the female proprietor of the hotel had the same last name as the male chef and proprietor of the more up-scale La Côte St. Jacques, where we had dinner reservations and where the rooms are expensive. The two establishments seem on good terms (Rive Gauche guests have exercise-room privileges at the Côte St. Jacques, if they're willing to walk 20 minutes to get there—the two places really ought to run a little ferry service across the river), so our theory is that the Rive Gauche is the project either of the wife, now that her children are grown, or of a grown-up daughter.

Once we were settled in (and I had gotten this photo through the kitchen door of the chefs preparing acres of cocktail muncies for a meeting/seminar in progress downstairs), we strolled along the river (where, at intervals along the bank, little signs on concrete posts identify the various water birds you can observe) to check out the Locaboat terminal, between the bridge and the hotel. The name comes from the French "loca-" signifying rental and the English "boat"—apparently the British are their best customers. The company has branches all over France (and several neighboring countries), which rent live-aboard pleasure boats of several sizes by the day or week. We've considered doing something like that for many years (since our hotel-barge cruise back in the '80s)—Buz and Kathy, what do you think? Here, David is standing in front of a "penichette" that sleeps 4 to 6 (our restaurant is actually visible in the distance, just to the left of the wheelhouse). Apparently, Locaboat is responsible for all those cabin cruisers and penichettes we've been seeing on the canals. You can even pick up a boat at one location and turn it in at another. Just Google "locaboat france" to see their slick and informative website, in much better English than most.

Once we were settled in (and I had gotten this photo through the kitchen door of the chefs preparing acres of cocktail muncies for a meeting/seminar in progress downstairs), we strolled along the river (where, at intervals along the bank, little signs on concrete posts identify the various water birds you can observe) to check out the Locaboat terminal, between the bridge and the hotel. The name comes from the French "loca-" signifying rental and the English "boat"—apparently the British are their best customers. The company has branches all over France (and several neighboring countries), which rent live-aboard pleasure boats of several sizes by the day or week. We've considered doing something like that for many years (since our hotel-barge cruise back in the '80s)—Buz and Kathy, what do you think? Here, David is standing in front of a "penichette" that sleeps 4 to 6 (our restaurant is actually visible in the distance, just to the left of the wheelhouse). Apparently, Locaboat is responsible for all those cabin cruisers and penichettes we've been seeing on the canals. You can even pick up a boat at one location and turn it in at another. Just Google "locaboat france" to see their slick and informative website, in much better English than most.

When dinner-time came, David was still frazzled from the drive, so rather than hiking around by the bridge, we just took the car—easy turns both going and coming, now that we knew the route—but when we presented ourselves at the door, at the location shown on my maps (and the address in the guides), it was locked, and a small sign said that, henceforth, reception would be located across the street. Apparently the chef, long stuck in his old location a block from the river, had finally gotten his hands on the building across the street, which overlooked the water, and had shifted reception and the restaurant to that side.

The bank of the river was very steep on that side, so the street-level entrance, on the side of the building away from the river, was a couple of floors above the water. We were escorted through the lobby, past this lovely library/lounge, to a glass-walled elevator and down one floor to restaurant level, which opened onto a broad balcony facing the river. One wall of the restaurant was covered with this highly decorative array of dried plant parts, displayed behind glass in deep picture frames.

The bank of the river was very steep on that side, so the street-level entrance, on the side of the building away from the river, was a couple of floors above the water. We were escorted through the lobby, past this lovely library/lounge, to a glass-walled elevator and down one floor to restaurant level, which opened onto a broad balcony facing the river. One wall of the restaurant was covered with this highly decorative array of dried plant parts, displayed behind glass in deep picture frames.

We opted to take our apperitifs on the terrace. I asked as usual for cassis syrup, and as usual, they didn't have it, "but you surely have crême de cassis, right? Could you mix that with water, just as though it were syrup?" The waiter seemed surprised, but they did it, and it was excellent—strongly currant flavored but not as sweet as a syrup. With the drinks came this first assortment of amuse-bouches. The cube at the left is cooked mackerel embedded in raspberry jelly; a hollow molded into the top surface is filled withvery thin vinegar-marinated carrot slices. Even David, who is not fond of oily fish, declared it not bad. Next is a small mackerel filet, marinated in lemon and tarragon, bent into an S-curve on its little skewer, and held in place by buttons of zucchini at each end. It's resting on a dab of mayonnaise. To the right of that is a dab of cooked fish spread straddled by three tiny shrimp, and on the right is a paper cone of "friture," tiny, whole deep-fried fish (smelts in this case), each no longer than my little finger, accompanied by a rosette of tartar sauce. David is also not fond of food with eyes, but he ate a couple of the smelts.

We opted to take our apperitifs on the terrace. I asked as usual for cassis syrup, and as usual, they didn't have it, "but you surely have crême de cassis, right? Could you mix that with water, just as though it were syrup?" The waiter seemed surprised, but they did it, and it was excellent—strongly currant flavored but not as sweet as a syrup. With the drinks came this first assortment of amuse-bouches. The cube at the left is cooked mackerel embedded in raspberry jelly; a hollow molded into the top surface is filled withvery thin vinegar-marinated carrot slices. Even David, who is not fond of oily fish, declared it not bad. Next is a small mackerel filet, marinated in lemon and tarragon, bent into an S-curve on its little skewer, and held in place by buttons of zucchini at each end. It's resting on a dab of mayonnaise. To the right of that is a dab of cooked fish spread straddled by three tiny shrimp, and on the right is a paper cone of "friture," tiny, whole deep-fried fish (smelts in this case), each no longer than my little finger, accompanied by a rosette of tartar sauce. David is also not fond of food with eyes, but he ate a couple of the smelts.

Amuse bouche: At the table, they served each of us two hot slices of boudin noir (black, i.e., blood, pudding) with cubes of caramelized apple and spoonfuls of mashed potato. It was beginning to look as though the chef had it in for David, but at least he didn't wrap the whole thing in cucumber. David even ate some of it.

First course: Four variations on foie gras "presented like sushi": Clockwise from the top right: (a) a circular slice of foie gras with asparagus jelly in the center and wrapped in a thin slice of asparagus; (b) a circular slice of foie gras coated with dried-fruit chutney and nuts; (c) thin slices of foie gras draped over a little salad; (d) a rectangular slice of foie gras wrapped in a leek leaf and covered with celery- and truffle-flavored tapioca pearls. At the top, two different shapes and flavors of toast. All very good, except the pink slices of pickled radish at the right, the rather strong smell of which David found revolting. What is it with this chef?

First course: Four variations on foie gras "presented like sushi": Clockwise from the top right: (a) a circular slice of foie gras with asparagus jelly in the center and wrapped in a thin slice of asparagus; (b) a circular slice of foie gras coated with dried-fruit chutney and nuts; (c) thin slices of foie gras draped over a little salad; (d) a rectangular slice of foie gras wrapped in a leek leaf and covered with celery- and truffle-flavored tapioca pearls. At the top, two different shapes and flavors of toast. All very good, except the pink slices of pickled radish at the right, the rather strong smell of which David found revolting. What is it with this chef?

Second course, me: "Gently cooked" skate's wing in a frothy spiced bouillon of coconut and kaffir lime (Citrus hystrix). Underneath, mostly hidden by the broth, were stewed tomato and sautéed baby vegetables. The decorative fan is the skeleton of the skate's wing, toasted crisp.

Second course, David: Crispy "bonbons" of "petits gris" (Helix aspersa, a less common variety of snail) with "virtual snail butter." At last, a course that did not actively put David off, but neither did he think it was anything special. The snails seemed to be wrapped in that finely shredded pastry used in Greek desserts, and the garlic-and-parsley foam in the center (which our server proudly announced contained not a speck of actual butter), although pleasant enough, didn't actually bear much resemblance to snail butter.

Second course, David: Crispy "bonbons" of "petits gris" (Helix aspersa, a less common variety of snail) with "virtual snail butter." At last, a course that did not actively put David off, but neither did he think it was anything special. The snails seemed to be wrapped in that finely shredded pastry used in Greek desserts, and the garlic-and-parsley foam in the center (which our server proudly announced contained not a speck of actual butter), although pleasant enough, didn't actually bear much resemblance to snail butter.

Third course: Lobster on a bed of puréed peas flavored with eucalyptus and accompanied by an acidulated sauce.

Fourth course: "Epigram" of lamb—a bit of braised shoulder wrapped in more crisp shredded pastry, an herb-coated chop from the rack, and a thick slice of filet—with carrots and sweet potatoes. The lamb was excellent, but the vegetables, sitting there looking modest, stole the show. The three round slices of yellow carrot were excellent, but the comet of sweet-potato purée was exquisite, set off perfectly by a little drizzle of "green anise" oil, and the two straight orange streaks were out of this world! "What is this stuff?" we asked the waiter (it had been a couple of hours since we read the menus). "Purple carrot, madame, cooked with vinegar." Wow. From what I've read, purple carrots (grown in some parts of Africa) have been a great disappointment to chefs—such decorative potential, such crummy flavor—but this guy had really found a way to tap their potential.

Fourth course: "Epigram" of lamb—a bit of braised shoulder wrapped in more crisp shredded pastry, an herb-coated chop from the rack, and a thick slice of filet—with carrots and sweet potatoes. The lamb was excellent, but the vegetables, sitting there looking modest, stole the show. The three round slices of yellow carrot were excellent, but the comet of sweet-potato purée was exquisite, set off perfectly by a little drizzle of "green anise" oil, and the two straight orange streaks were out of this world! "What is this stuff?" we asked the waiter (it had been a couple of hours since we read the menus). "Purple carrot, madame, cooked with vinegar." Wow. From what I've read, purple carrots (grown in some parts of Africa) have been a great disappointment to chefs—such decorative potential, such crummy flavor—but this guy had really found a way to tap their potential.

Cheese, David: Chaource, Comté, Roquefort. Cheese, me: Tomme de brebis, St. Paulin, Chaource. All ovvered with a choice of walnuts, huge grapes, blueberry jam, and/or prunes.

Predessert: A small fresh-raspberry and lime tart to share.

Predessert: A small fresh-raspberry and lime tart to share.

Mignardises: The usual assortment of fruit pastes, macaroons, etc. Green-tea-flavored crême brulées. Grapefruit granités. I don't even remember what the little dishes of yellow stuff were.

First dessert: (Ha! And you thought we were winding down.) Theme and variations on hazelnut. Hazelnut cake, hazelnut ice cream, hazelnut pudding, and (the best) a thick smear of chocolate laced with crumbled hazelnut brittle.

Second dessert: A sort of nest made out of crystallized rose petals and sheets of almond nougatine glued (with hard caramel) to a base, filled with a scoop of rose-flavored ice cream and surrounded by fresh strawberries and blueberries in rose syrup.

Second dessert: A sort of nest made out of crystallized rose petals and sheets of almond nougatine glued (with hard caramel) to a base, filled with a scoop of rose-flavored ice cream and surrounded by fresh strawberries and blueberries in rose syrup.

Finally, with the check, a couple of "Dagmar" candies (hard caramel shell, chocolate inside), together with the lid of the tin they come in, to remind us that tins of them were on sale in the lobby, should we wish to continue eating on our way back to the hotel.

previous entry

List of Entries

next entry

Yes, on Wednesday, we were to drive from from Chablis to Joigny, but nobody every accused us of taking the shortest route between two points in France. First, of course, we had our 90-minute "Vititour" scheduled for 10 a.m. After that, we wanted to take in Ancy-le-Franc castle on the way to Joigny—even though Chablis to Ancy was about as far as Chablis to Joigny, and in exactly the opposite direction.

Yes, on Wednesday, we were to drive from from Chablis to Joigny, but nobody every accused us of taking the shortest route between two points in France. First, of course, we had our 90-minute "Vititour" scheduled for 10 a.m. After that, we wanted to take in Ancy-le-Franc castle on the way to Joigny—even though Chablis to Ancy was about as far as Chablis to Joigny, and in exactly the opposite direction.

At the top, at the boundary between the trees and the vines, was this orientation table, on which Franck pointed out the locations and exposures of the four grades of vinyard—grand cru, premier cru, Chablis, and petit Chablis. Those vines directly in front of us are in the grand cru area, the Les Grenouilles sector, I think. He also showed us this chunk of Chablis subsoil, and "soil" is used rather loosely here—it was basically a piece of rock. Note all the little seashells embedded in it—those are Ostrea virgula, little comma-shaped Jurassic oysters characteristic of the Kimmeridgean soils that give Chablis wines their very mineral character. Their keeping qualities, much better than most whites, are also chalked up (as it were) to their mineral content. On tops of the ridges and on plateaus, the Kimmeridgean soils are covered by Portlandian ones, so those areas are only "petit Chablis. He reminisced about a recent vintage year in which the weather was completely haywire. "It was strange," he said, "you'd think we were living in Meursault instead of Chablis! We didn't really make Chablis that year; we made Meursault. It didn't keep worth a darn, but it was really good!"

At the top, at the boundary between the trees and the vines, was this orientation table, on which Franck pointed out the locations and exposures of the four grades of vinyard—grand cru, premier cru, Chablis, and petit Chablis. Those vines directly in front of us are in the grand cru area, the Les Grenouilles sector, I think. He also showed us this chunk of Chablis subsoil, and "soil" is used rather loosely here—it was basically a piece of rock. Note all the little seashells embedded in it—those are Ostrea virgula, little comma-shaped Jurassic oysters characteristic of the Kimmeridgean soils that give Chablis wines their very mineral character. Their keeping qualities, much better than most whites, are also chalked up (as it were) to their mineral content. On tops of the ridges and on plateaus, the Kimmeridgean soils are covered by Portlandian ones, so those areas are only "petit Chablis. He reminisced about a recent vintage year in which the weather was completely haywire. "It was strange," he said, "you'd think we were living in Meursault instead of Chablis! We didn't really make Chablis that year; we made Meursault. It didn't keep worth a darn, but it was really good!"

From there, we drove back down the hill, around the town, and back up the hill on the other side, to a clearing at the top edge of the vines. On the way, Franck gave us some statistics. Burgundy as a whole harbors 101 appellations controlées (legally protected named points of origin), only 30 or so of which are grands crus. Around Chablis are 4700 ha of the "chablis" grade but only 100 ha of grands crus, all contiguous in a one 1-km stretch along the D65. Chablis produces about 20 million bottles of wine a year, 80% of which are exported. Only about 10% of Chablis is matured in oak; the rest, of grades that would not benefit from the process or wouldn't command a price that would justify the expense, are matured in stainless steel. The grapes are harvested, as a rule of thumb, 100 days after the vines flower (the vines are obligate selfers; no pollinator needed). In the photo on the left, we're looking across the valley (with the town of Chablis in the bottom) at the hillside of grands crus on the other side. The largest white roof in the town is the coop, for small or beginning growers not ready to go independent yet. (As we drove back through town later, Franck pointed out, in order as we passed them, the elementary school, the secondary school, and the coop. "A natural progression, as we like to say around here.")

From there, we drove back down the hill, around the town, and back up the hill on the other side, to a clearing at the top edge of the vines. On the way, Franck gave us some statistics. Burgundy as a whole harbors 101 appellations controlées (legally protected named points of origin), only 30 or so of which are grands crus. Around Chablis are 4700 ha of the "chablis" grade but only 100 ha of grands crus, all contiguous in a one 1-km stretch along the D65. Chablis produces about 20 million bottles of wine a year, 80% of which are exported. Only about 10% of Chablis is matured in oak; the rest, of grades that would not benefit from the process or wouldn't command a price that would justify the expense, are matured in stainless steel. The grapes are harvested, as a rule of thumb, 100 days after the vines flower (the vines are obligate selfers; no pollinator needed). In the photo on the left, we're looking across the valley (with the town of Chablis in the bottom) at the hillside of grands crus on the other side. The largest white roof in the town is the coop, for small or beginning growers not ready to go independent yet. (As we drove back through town later, Franck pointed out, in order as we passed them, the elementary school, the secondary school, and the coop. "A natural progression, as we like to say around here.") In the photo on the right (above), he points out to us the shoot that he would choose to initiate next year's growth. In the winter, he's a vine pruner by trade. An experienced worker like him can prune about a hectare of vines in a month, choosing a single shoot to preserve, triming to to 6-8 buds, pruning away all the other growth, then bending the single shoot down along the trellis wire and tying it in place. The photo to the right here is of a page in his notebook of illustrations, showing hail damage. I asked him about the "Hailed vine is a smoked vine" proverb—what is a "smoked vine"? He'd never heard the expression, but he assured us that hail is the winemaker's greatest fear, that a hailed vine is a severely damaged vine. As the photo shows, almost all the grapes were pierced by hailstone strikes and therefore either dried up or rotted, and the stems are covered with scars where the hailstones broke or bruised the tender bark earlier in the season. No matter what shoot the pruner chooses to preserve, those scars will make it brittle, and when he tries to bend it to the trellis, it will inevitably break off short, leaving only one or two buds to grow in the coming season.

In the photo on the right (above), he points out to us the shoot that he would choose to initiate next year's growth. In the winter, he's a vine pruner by trade. An experienced worker like him can prune about a hectare of vines in a month, choosing a single shoot to preserve, triming to to 6-8 buds, pruning away all the other growth, then bending the single shoot down along the trellis wire and tying it in place. The photo to the right here is of a page in his notebook of illustrations, showing hail damage. I asked him about the "Hailed vine is a smoked vine" proverb—what is a "smoked vine"? He'd never heard the expression, but he assured us that hail is the winemaker's greatest fear, that a hailed vine is a severely damaged vine. As the photo shows, almost all the grapes were pierced by hailstone strikes and therefore either dried up or rotted, and the stems are covered with scars where the hailstones broke or bruised the tender bark earlier in the season. No matter what shoot the pruner chooses to preserve, those scars will make it brittle, and when he tries to bend it to the trellis, it will inevitably break off short, leaving only one or two buds to grow in the coming season.

Finally, as the tour drew to a close, Franck opened up the back of his van and produced, a little folding table, two glasses, and a half bottle of wine made by a family who've been making wine for 13 generations. A very good tour. Just Google "Chablis Vititours" to see Franck's website.

Finally, as the tour drew to a close, Franck opened up the back of his van and produced, a little folding table, two glasses, and a half bottle of wine made by a family who've been making wine for 13 generations. A very good tour. Just Google "Chablis Vititours" to see Franck's website.

Back at Hostellerie des Clos, we bid farefwell to the single goldfish, in a handsome glass bowl with a few black stones in the bottom, that graces the lobby, packed up the car, and headed for Ancy le Franc. We got there at lunchtime and began the usual search for a suitable eatery. Eventually, we followed the signs several kilometers out of town, along the canal, to lock #79, where sat overlooking the canal at a little hotel-restaurant called, appropriately enough, L'Écluse, "the lock." No actual boats cruised by while we were there, but foot and bicycle traffic on the towpath on the opposite bank was endlessly entertaining. One couple toodled by on a bicycle built for two on which the front seat was recumbant and the rear seat upright. They were packing goodsized saddlebags and might actually have been travelling somewhere.

Back at Hostellerie des Clos, we bid farefwell to the single goldfish, in a handsome glass bowl with a few black stones in the bottom, that graces the lobby, packed up the car, and headed for Ancy le Franc. We got there at lunchtime and began the usual search for a suitable eatery. Eventually, we followed the signs several kilometers out of town, along the canal, to lock #79, where sat overlooking the canal at a little hotel-restaurant called, appropriately enough, L'Écluse, "the lock." No actual boats cruised by while we were there, but foot and bicycle traffic on the towpath on the opposite bank was endlessly entertaining. One couple toodled by on a bicycle built for two on which the front seat was recumbant and the rear seat upright. They were packing goodsized saddlebags and might actually have been travelling somewhere.

David had a salad topped with goat cheese on large croutons and a drift of outstandingly tasty toasted pine nuts. I ordered the "salade façon tartiflette"—wasn't that some sort of ham and cheese pie? Sure enough, my salad came topped with a large serving (only a fraction of which shows in the photo)of tartiflette, a layer of thick cooked-potato slices liberally topped with lardons, then a thick layer of reblochon cheese and run under the broiler. Yum! I had always assumed tartiflette was a traditional dish, but it turns out to have been invented and promoted in the 1980's by (who else?) the makers of reblochon.

David had a salad topped with goat cheese on large croutons and a drift of outstandingly tasty toasted pine nuts. I ordered the "salade façon tartiflette"—wasn't that some sort of ham and cheese pie? Sure enough, my salad came topped with a large serving (only a fraction of which shows in the photo)of tartiflette, a layer of thick cooked-potato slices liberally topped with lardons, then a thick layer of reblochon cheese and run under the broiler. Yum! I had always assumed tartiflette was a traditional dish, but it turns out to have been invented and promoted in the 1980's by (who else?) the makers of reblochon.

Ancy-le-Franc was built between 1542 and 1550 from plans by Sebastiano Serlio and is resolutely Renaissance and resolutely symmetrical. Serlio liked symmetry, and he liked what he called "rhythm" in the alternation of masses and voids along a surface, so we found nothing trapezoidal, unfinished, or haphazard here. On the left is one facade of the château (all four sides are similar, of course) and on the right the stable block, not included in the tour.

Ancy-le-Franc was built between 1542 and 1550 from plans by Sebastiano Serlio and is resolutely Renaissance and resolutely symmetrical. Serlio liked symmetry, and he liked what he called "rhythm" in the alternation of masses and voids along a surface, so we found nothing trapezoidal, unfinished, or haphazard here. On the left is one facade of the château (all four sides are similar, of course) and on the right the stable block, not included in the tour.

Once we were settled in (and I had gotten this photo through the kitchen door of the chefs preparing acres of cocktail muncies for a meeting/seminar in progress downstairs), we strolled along the river (where, at intervals along the bank, little signs on concrete posts identify the various water birds you can observe) to check out the Locaboat terminal, between the bridge and the hotel. The name comes from the French "loca-" signifying rental and the English "boat"—apparently the British are their best customers. The company has branches all over France (and several neighboring countries), which rent live-aboard pleasure boats of several sizes by the day or week. We've considered doing something like that for many years (since our hotel-barge cruise back in the '80s)—Buz and Kathy, what do you think? Here, David is standing in front of a "penichette" that sleeps 4 to 6 (our restaurant is actually visible in the distance, just to the left of the wheelhouse). Apparently, Locaboat is responsible for all those cabin cruisers and penichettes we've been seeing on the canals. You can even pick up a boat at one location and turn it in at another. Just Google "locaboat france" to see their slick and informative website, in much better English than most.

Once we were settled in (and I had gotten this photo through the kitchen door of the chefs preparing acres of cocktail muncies for a meeting/seminar in progress downstairs), we strolled along the river (where, at intervals along the bank, little signs on concrete posts identify the various water birds you can observe) to check out the Locaboat terminal, between the bridge and the hotel. The name comes from the French "loca-" signifying rental and the English "boat"—apparently the British are their best customers. The company has branches all over France (and several neighboring countries), which rent live-aboard pleasure boats of several sizes by the day or week. We've considered doing something like that for many years (since our hotel-barge cruise back in the '80s)—Buz and Kathy, what do you think? Here, David is standing in front of a "penichette" that sleeps 4 to 6 (our restaurant is actually visible in the distance, just to the left of the wheelhouse). Apparently, Locaboat is responsible for all those cabin cruisers and penichettes we've been seeing on the canals. You can even pick up a boat at one location and turn it in at another. Just Google "locaboat france" to see their slick and informative website, in much better English than most.

The bank of the river was very steep on that side, so the street-level entrance, on the side of the building away from the river, was a couple of floors above the water. We were escorted through the lobby, past this lovely library/lounge, to a glass-walled elevator and down one floor to restaurant level, which opened onto a broad balcony facing the river. One wall of the restaurant was covered with this highly decorative array of dried plant parts, displayed behind glass in deep picture frames.

The bank of the river was very steep on that side, so the street-level entrance, on the side of the building away from the river, was a couple of floors above the water. We were escorted through the lobby, past this lovely library/lounge, to a glass-walled elevator and down one floor to restaurant level, which opened onto a broad balcony facing the river. One wall of the restaurant was covered with this highly decorative array of dried plant parts, displayed behind glass in deep picture frames.

We opted to take our apperitifs on the terrace. I asked as usual for cassis syrup, and as usual, they didn't have it, "but you surely have crême de cassis, right? Could you mix that with water, just as though it were syrup?" The waiter seemed surprised, but they did it, and it was excellent—strongly currant flavored but not as sweet as a syrup. With the drinks came this first assortment of amuse-bouches. The cube at the left is cooked mackerel embedded in raspberry jelly; a hollow molded into the top surface is filled withvery thin vinegar-marinated carrot slices. Even David, who is not fond of oily fish, declared it not bad. Next is a small mackerel filet, marinated in lemon and tarragon, bent into an S-curve on its little skewer, and held in place by buttons of zucchini at each end. It's resting on a dab of mayonnaise. To the right of that is a dab of cooked fish spread straddled by three tiny shrimp, and on the right is a paper cone of "friture," tiny, whole deep-fried fish (smelts in this case), each no longer than my little finger, accompanied by a rosette of tartar sauce. David is also not fond of food with eyes, but he ate a couple of the smelts.

We opted to take our apperitifs on the terrace. I asked as usual for cassis syrup, and as usual, they didn't have it, "but you surely have crême de cassis, right? Could you mix that with water, just as though it were syrup?" The waiter seemed surprised, but they did it, and it was excellent—strongly currant flavored but not as sweet as a syrup. With the drinks came this first assortment of amuse-bouches. The cube at the left is cooked mackerel embedded in raspberry jelly; a hollow molded into the top surface is filled withvery thin vinegar-marinated carrot slices. Even David, who is not fond of oily fish, declared it not bad. Next is a small mackerel filet, marinated in lemon and tarragon, bent into an S-curve on its little skewer, and held in place by buttons of zucchini at each end. It's resting on a dab of mayonnaise. To the right of that is a dab of cooked fish spread straddled by three tiny shrimp, and on the right is a paper cone of "friture," tiny, whole deep-fried fish (smelts in this case), each no longer than my little finger, accompanied by a rosette of tartar sauce. David is also not fond of food with eyes, but he ate a couple of the smelts.

First course: Four variations on foie gras "presented like sushi": Clockwise from the top right: (a) a circular slice of foie gras with asparagus jelly in the center and wrapped in a thin slice of asparagus; (b) a circular slice of foie gras coated with dried-fruit chutney and nuts; (c) thin slices of foie gras draped over a little salad; (d) a rectangular slice of foie gras wrapped in a leek leaf and covered with celery- and truffle-flavored tapioca pearls. At the top, two different shapes and flavors of toast. All very good, except the pink slices of pickled radish at the right, the rather strong smell of which David found revolting. What is it with this chef?

First course: Four variations on foie gras "presented like sushi": Clockwise from the top right: (a) a circular slice of foie gras with asparagus jelly in the center and wrapped in a thin slice of asparagus; (b) a circular slice of foie gras coated with dried-fruit chutney and nuts; (c) thin slices of foie gras draped over a little salad; (d) a rectangular slice of foie gras wrapped in a leek leaf and covered with celery- and truffle-flavored tapioca pearls. At the top, two different shapes and flavors of toast. All very good, except the pink slices of pickled radish at the right, the rather strong smell of which David found revolting. What is it with this chef?

Second course, David: Crispy "bonbons" of "petits gris" (Helix aspersa, a less common variety of snail) with "virtual snail butter." At last, a course that did not actively put David off, but neither did he think it was anything special. The snails seemed to be wrapped in that finely shredded pastry used in Greek desserts, and the garlic-and-parsley foam in the center (which our server proudly announced contained not a speck of actual butter), although pleasant enough, didn't actually bear much resemblance to snail butter.

Second course, David: Crispy "bonbons" of "petits gris" (Helix aspersa, a less common variety of snail) with "virtual snail butter." At last, a course that did not actively put David off, but neither did he think it was anything special. The snails seemed to be wrapped in that finely shredded pastry used in Greek desserts, and the garlic-and-parsley foam in the center (which our server proudly announced contained not a speck of actual butter), although pleasant enough, didn't actually bear much resemblance to snail butter.

Fourth course: "Epigram" of lamb—a bit of braised shoulder wrapped in more crisp shredded pastry, an herb-coated chop from the rack, and a thick slice of filet—with carrots and sweet potatoes. The lamb was excellent, but the vegetables, sitting there looking modest, stole the show. The three round slices of yellow carrot were excellent, but the comet of sweet-potato purée was exquisite, set off perfectly by a little drizzle of "green anise" oil, and the two straight orange streaks were out of this world! "What is this stuff?" we asked the waiter (it had been a couple of hours since we read the menus). "Purple carrot, madame, cooked with vinegar." Wow. From what I've read, purple carrots (grown in some parts of Africa) have been a great disappointment to chefs—such decorative potential, such crummy flavor—but this guy had really found a way to tap their potential.

Fourth course: "Epigram" of lamb—a bit of braised shoulder wrapped in more crisp shredded pastry, an herb-coated chop from the rack, and a thick slice of filet—with carrots and sweet potatoes. The lamb was excellent, but the vegetables, sitting there looking modest, stole the show. The three round slices of yellow carrot were excellent, but the comet of sweet-potato purée was exquisite, set off perfectly by a little drizzle of "green anise" oil, and the two straight orange streaks were out of this world! "What is this stuff?" we asked the waiter (it had been a couple of hours since we read the menus). "Purple carrot, madame, cooked with vinegar." Wow. From what I've read, purple carrots (grown in some parts of Africa) have been a great disappointment to chefs—such decorative potential, such crummy flavor—but this guy had really found a way to tap their potential.

Predessert: A small fresh-raspberry and lime tart to share.

Predessert: A small fresh-raspberry and lime tart to share.

Second dessert: A sort of nest made out of crystallized rose petals and sheets of almond nougatine glued (with hard caramel) to a base, filled with a scoop of rose-flavored ice cream and surrounded by fresh strawberries and blueberries in rose syrup.

Second dessert: A sort of nest made out of crystallized rose petals and sheets of almond nougatine glued (with hard caramel) to a base, filled with a scoop of rose-flavored ice cream and surrounded by fresh strawberries and blueberries in rose syrup.