Tuesday, 12 July 2016, Valence to Grenoble

Written 27 July 2016

In the morning, still no cold water in the sink. In the end, we decided against waiting around until the art museum opened in the afternoon, so we packed up at our leisure and drove on to Grenoble, about an hour. The agriculture along the way ran to corn (just coming into tassel), young sunflowers not yet in bloom, peach orchards, melons, and fruit trees (maybe apples). Also many hayfields, just cut and baled. A little scotch broom was blooming along the roadsides; in Crete, it had already gone to seed. Not much in the way of grapes. A few orchards that could have been cherries, and a nut oil factory, which showed up before the first groves of walnuts appeared.

I was delighted actualy to be able to call ahead—on our newly Europe-enabled smartphone—to ask how to get to the hotel (which is on a pedestrian street) and into its garage (whose entrance must clearly be elsewhere). As a result, we were able to change the GPS target to the address of the garage, around the corner from the hotel, drove right in, buzzed reception to open the gate, parked in the Ibis spaces, and strolled our luggage to the elevator that took us straight up to Reception on the second floor. To get from there to our rooms (which were actually ready at 11 a.m.!) we took that elevator up two more floors; to get out to the street we took that elevator back down to reception, then a different one down one floor to an empty room opening onto the sidewalk of the pedestrian street. Both elevators had two doors, so it was a constant mental exercise to remember which one you were in and which door was likely to open to let you out.

The rooms were pretty much standard Ibis rooms, purpose built, good showers, but smallish. If I ducked down a little, I had a nice view of the Grenoble Bastille from my window, although when we arrived, it was solidly socked in.

Once we'd settled in, we walked around the corner (the other direction from the parking garage) and found ourselves in a large pedestrian plaza, one side of which was lined with with restaurants. We chose Le Cafe du Marais, where they seated us upstairs, with a view over the plaza.

Once we'd settled in, we walked around the corner (the other direction from the parking garage) and found ourselves in a large pedestrian plaza, one side of which was lined with with restaurants. We chose Le Cafe du Marais, where they seated us upstairs, with a view over the plaza.

David ordered the "salade paysanne," the peasant salad. It came topped with diced ham, diced comté-type cheese, hard boiled egg, little round packaged croutons, and (in addition to the vinaigrette on the lettuce) a nice balsamic drizzle.

I ordered chicken liver salad, which came topped with boiled egg, the same croutons and balsamic drizzle, and lots of hot sautéed chicken livers, correctly cooked and still pink inside. Behind and to the left of my salad, you can see the little Lipton bottle from David's peach-flavored iced tea.

The Café du Marais is distinguished by this wonderful mural of Dali in its stairway.

The Café du Marais is distinguished by this wonderful mural of Dali in its stairway.

I have no idea whether Dali had anything in particular to do with this restaurant or with Grenoble. Maybe the owners are just fans. I think the rectangular object with the blue things in it was a little cabinet of Red Bull.

It was raining, and the Bastille was still fogged in, so rather than starting with that, we walked to the Museum of the Resistance and Deportation (the only one open on Tuesdays, and that only in the afternoon), where we wore our feet out before hiking back to the hotel to change for dinner. We knew right where the restaurant was, because we passed it both going to the musuem and coming back.

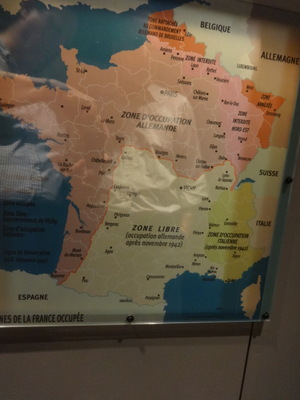

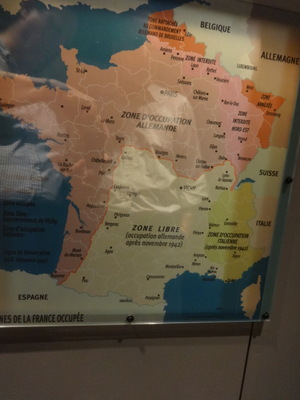

The museum was excellent, and it allowed photography, but although I took many photographs, they were mainly of text that I didn't have time to read all of or thought I would have trouble remembering. It presented a huge amount of information on the Resistance in the mountainous Grenoble region, including photos and life stories of many, many individual resistance fighters, their weaponry and strategies, and even a large relief map showing the locations of major Resistance camps and instances of the fighers' actions, divided up by category—you could press a button to light up all the cases of direct confrontation with enemy troops, all the cases of sabotage, all the assassinations, etc. In addition, whole areas were devoted to the deportation of Jews and others the Germans considered undesirable, as well as to individuals and institutions that harbored and hid potential deportees. For example, a group of nuns ran a girls' school, at which many Jewish girls lived and attended openly under false names and identities cooked up by the nuns.

The museum was excellent, and it allowed photography, but although I took many photographs, they were mainly of text that I didn't have time to read all of or thought I would have trouble remembering. It presented a huge amount of information on the Resistance in the mountainous Grenoble region, including photos and life stories of many, many individual resistance fighters, their weaponry and strategies, and even a large relief map showing the locations of major Resistance camps and instances of the fighers' actions, divided up by category—you could press a button to light up all the cases of direct confrontation with enemy troops, all the cases of sabotage, all the assassinations, etc. In addition, whole areas were devoted to the deportation of Jews and others the Germans considered undesirable, as well as to individuals and institutions that harbored and hid potential deportees. For example, a group of nuns ran a girls' school, at which many Jewish girls lived and attended openly under false names and identities cooked up by the nuns.

As background, the museum provided a lot of information about Grenoble itself, its history, and its role as a major destination, for some time before as well as during the war, for those fleeing Nazi agression elsewhere.

One of the most surprising things I learned was that, in addition to Occupied (northern) France and "Free" (southern) France (actually under German rule but not officially "occupied"), a third zone, which included Valence and Grenoble, was (after Novmeber of 1942) under Italian occupation! I had no idea. The two maps above show, at the left, the well known two zones and, at the right, the extent of the Italian-occupied zone. Sorry about all the glare and reflections—I couldn't get a clearer shot).

Tomorrow we'll have our choice of museums, and I'd still like to ride the cablecar up to the Bastille, even if the weather doesn't clear up.

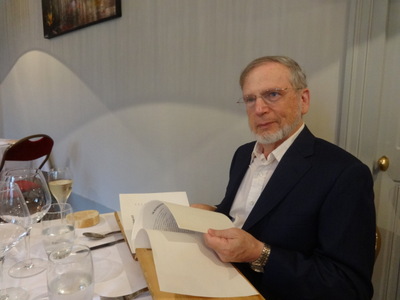

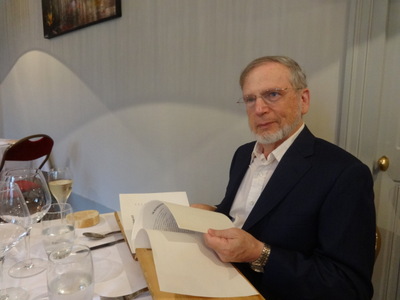

Dinner was at Fantin Latour, the highest ranked restaurant so far on the trip at four Gault-Millau toques. We never did figure out the connection, if any, of the restaurant with the painter of the same name (Henri Fantin-Latour, 1836–1904, of whose work I'm very fond; he did wonderful floral still lives). The artist was born in Grenoble, although nobody seems willing to say just where, and the door to the restaurant (behind David in the left-hand photo) says "Fantin Museum" over it, though I've found no explanation anywhere of what that has to do with either the painter or the restaurant. None of the restaurant's decor involved the artist's work.

Dinner was at Fantin Latour, the highest ranked restaurant so far on the trip at four Gault-Millau toques. We never did figure out the connection, if any, of the restaurant with the painter of the same name (Henri Fantin-Latour, 1836–1904, of whose work I'm very fond; he did wonderful floral still lives). The artist was born in Grenoble, although nobody seems willing to say just where, and the door to the restaurant (behind David in the left-hand photo) says "Fantin Museum" over it, though I've found no explanation anywhere of what that has to do with either the painter or the restaurant. None of the restaurant's decor involved the artist's work.

The right-hand photo is of David, later, as he studied the wine list, bound between two slabs of wood.

I don't remember whether I've mentioned it earlier in the diary, but back in Crete, I opened my e-mail one afternoon and found two messages from this restaurant waiting for me. The first one said that they much regretted that they had to cancel our reservation—they were hosting a group that night, which had suddenly gotten much larger; was there some other night we could come? (We would be in Grenoble for only two nights, so I was already formulating my reply to the effect that they, the restaurant cancelling on us, should be the ones to call our other Grenoble restaurant to see whether we could swap nights.) But fortunately, the second message, sent just half an hour later, said never mind, they had figured out how to make it work and looked forward to welcoming us as originally planned.

When we arrived, we were ushered upstairs to a rather bare room furnished with half a dozen card tables and folding chairs. On further investigation, beneath the lovely linens and glassware, the tables proved to be actual wooden tables with central wooden legs, but the chairs, red velour upholstery notwithstanding, were ordinary metal folding chairs. All the tables were filled in the course of the evening—this was clearly the solution they had found to accommodating those with reservations who were displaced by the very large group, whom we could her disporting themselves noisily downstairs.

From the time she first seated us, our waitress told us proudly that tonight we would eat plants. The chef believed strongly in eating plants and went so far as to collected them himself, both in the wild and from those he had transplanted to his garden. The table was even provided with a small handmade booklet, tied together with a ribbon, that included photos and descriptions of "The plants used by the chef."

From the time she first seated us, our waitress told us proudly that tonight we would eat plants. The chef believed strongly in eating plants and went so far as to collected them himself, both in the wild and from those he had transplanted to his garden. The table was even provided with a small handmade booklet, tied together with a ribbon, that included photos and descriptions of "The plants used by the chef."

We settled on the menu "Ascension des Cimes" (Ascension of the peaks). The amuse-bouche, shown in the left-hand photo was a vichysoisse atop a spinach puree perfumed with "épiaire" (Stachys sp., one of the chef's plants) sprinkled with glazed hazelnuts. The booklet (visible at the left, in front of the Evian bottle) listed only 14 plants—what, I asked myself, were the potatoes, spinach, and hazelnuts? Chopped liver? They certainly weren't listed among the plants used by the chef. The vichyssoise of the top layer was very good, but I found the spinach at the bottom far too vinegary.

At the right is the first listed course, a light mousseline of potatoes with red onion, "cebettes" (a special small variety of onion), crumbled nuts, and two more of the chef's plants (the pink flowers): "serpolet" (a variety of thyme) and "origan" (oregano). Again, apparently only the last two qualified as "plants"; he didn't even count the fennel sprig. The waitress assured us that everything on the plate was edible, as indeed it proved to be.

The second course was a "melting risotto of amaranth" surrounded by "crispy spring vegetables" and "aromatic herbs from the garden." It was beautiful, and tasty too. The risotto was so melting that the tiny amaranth seeds settled into a single layer in the center of the plate, and their foamy yellow sauce rose to the surface to hide them completely. The waitress specified that we need not feel obliged to eat the pea pod. The peas inside were delicious, and as a small gesture of defiance, I ate part of the inner lining of the pod, too. The brown-topped ring-shaped objects around the top of the plate were intriguing. The chef had cut an inch-long section from some sort of green onion or leek stem and charred one end of it, then separated the it into cylinders and stood them charred-end-up on the plate. Yummy.

The second course was a "melting risotto of amaranth" surrounded by "crispy spring vegetables" and "aromatic herbs from the garden." It was beautiful, and tasty too. The risotto was so melting that the tiny amaranth seeds settled into a single layer in the center of the plate, and their foamy yellow sauce rose to the surface to hide them completely. The waitress specified that we need not feel obliged to eat the pea pod. The peas inside were delicious, and as a small gesture of defiance, I ate part of the inner lining of the pod, too. The brown-topped ring-shaped objects around the top of the plate were intriguing. The chef had cut an inch-long section from some sort of green onion or leek stem and charred one end of it, then separated the it into cylinders and stood them charred-end-up on the plate. Yummy.

Next, the butter arrived, together with some bread. The butter had been flattened out into a thin layer, spread with herbs and saffron threads, then rolled up and sliced into cylinders for serving. It arrived on top of a chilled rock—not a slab of slate or a smooth pebble, but a thorough-going lumpy rock.

The menu listed St. Pierre (Zeus faber) as the fish course, but apparently the market let the kitchen down, and they had substituted swordfish (Xiphias gladius). It arrived on a slab of slate and a rock. The slate served as the plate, the rock, heated to a blazing temperature, was set on it, and the chunk of swordfish was slapped on top of that, where it sizzled loudly all the way to the table, then topped with some cooked vegetables (not, apparently, plants). It had been marinated in an infusion of "wild absinthe," by which I assume the chef meant wormwood, Artemisia absinthium, and was garnished with a sprig of the fresh plant, which the waitress advised us not to eat, as it would be very bitter. The fish was delicious—you don't often get swordfish that, despite a nicely crisped finish on the underside, hasn't been overcooked. The rock was still too hot to touch comfortably when we finished and they took it away.

The menu listed St. Pierre (Zeus faber) as the fish course, but apparently the market let the kitchen down, and they had substituted swordfish (Xiphias gladius). It arrived on a slab of slate and a rock. The slate served as the plate, the rock, heated to a blazing temperature, was set on it, and the chunk of swordfish was slapped on top of that, where it sizzled loudly all the way to the table, then topped with some cooked vegetables (not, apparently, plants). It had been marinated in an infusion of "wild absinthe," by which I assume the chef meant wormwood, Artemisia absinthium, and was garnished with a sprig of the fresh plant, which the waitress advised us not to eat, as it would be very bitter. The fish was delicious—you don't often get swordfish that, despite a nicely crisped finish on the underside, hasn't been overcooked. The rock was still too hot to touch comfortably when we finished and they took it away.

Next came lobster, extracted from the shell, dressed with a sauce of chartreuse and orange, put back into the shell, and broiled. Very good, though I thought it needed a little lemon. It was again garnished with several of the chef's plants.

Before the meat course, we were served a palate-cleanser—a three-layered juice and sherbet concoction of orange.

Before the meat course, we were served a palate-cleanser—a three-layered juice and sherbet concoction of orange.

David had chosen the rack of lamb, which was billed on the menu as "like a walk in the forest." The chef achieved the forest-like flavor by searing the lamb, cutting the chops apart, packing them into a sealed mason jar together with large wet chunks of bark and leafy twigs from a larch tree (Larix decidua), Europe's only deciduous conifer, and finishing off the cooking there. David said they were good but not notably forest-flavored.

My meat course was quail "perfumed with catnip" accompanied by a pool of thick, sweet beet-root sauce. Very good. Both meat courses came with a cooked baby carrot, a heap of sweet and sour shredded cabbage, and some red quinoa. I'm not sure what the greenish puree under David's other vegetables was—perhaps potato.

My meat course was quail "perfumed with catnip" accompanied by a pool of thick, sweet beet-root sauce. Very good. Both meat courses came with a cooked baby carrot, a heap of sweet and sour shredded cabbage, and some red quinoa. I'm not sure what the greenish puree under David's other vegetables was—perhaps potato.

The cheese course was a set assortment of three: morbier (the one with the trademark gray streak through it), a tomme of some sort, and chevre montagnard. They came with a splodge of wild blueberry jam and a few toasted pumpkin seeds. The gray streak through morbier is a thin layer of carefully sifted wood ash. It separates the part of the cheese made from the morning milking from that made from the evening milking. No, I'm not kidding.

David's dessert was a small disk of intense chocolate cream topped with a little quenelle of ice cream and a few almonds in crisp caramel shells.

David's dessert was a small disk of intense chocolate cream topped with a little quenelle of ice cream and a few almonds in crisp caramel shells.

Mine was a mixture of fresh strawberries and strawberries poached in "delicately spiced wine," accompanied by strawberry sorbet, a crisp French-style praline (the red pebbly thing at the left), and a mound of jasmine-flavored sabayon sauce. I'm pretty sure that's a catnip leaf on top, although the menu didn't mention it.

The meal was very good, but in several places, I thought the chef had rather too heavy a hand with the vinegar. I aso got a little tired of the waitress's endless chipper emphasis on the chef's plants, which she seemed to find a very novel concept, as though we'd never eaten plants before. We also had difficulty picking out all the flavors supposedly imparted by the plant-based marinades and infusions, at least partly because, never having eaten those plants before, we didn't know what they should taste like.

The plant theme was continued up and down the stairs, which were decorated with garlands made of hundreds upon hundreds of dried ginkgo leaves, threaded on strings, and out the corridor to the street, which was decorated as a mountain stream with real ferns and mosses.

You can Google the restaurant to see photos of the lovely main dining room, as well as the gorgeous façade of the house and beautiful gardens, none of which we ever saw.

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

Once we'd settled in, we walked around the corner (the other direction from the parking garage) and found ourselves in a large pedestrian plaza, one side of which was lined with with restaurants. We chose Le Cafe du Marais, where they seated us upstairs, with a view over the plaza.

Once we'd settled in, we walked around the corner (the other direction from the parking garage) and found ourselves in a large pedestrian plaza, one side of which was lined with with restaurants. We chose Le Cafe du Marais, where they seated us upstairs, with a view over the plaza.

The Café du Marais is distinguished by this wonderful mural of Dali in its stairway.

The Café du Marais is distinguished by this wonderful mural of Dali in its stairway.

The museum was excellent, and it allowed photography, but although I took many photographs, they were mainly of text that I didn't have time to read all of or thought I would have trouble remembering. It presented a huge amount of information on the Resistance in the mountainous Grenoble region, including photos and life stories of many, many individual resistance fighters, their weaponry and strategies, and even a large relief map showing the locations of major Resistance camps and instances of the fighers' actions, divided up by category—you could press a button to light up all the cases of direct confrontation with enemy troops, all the cases of sabotage, all the assassinations, etc. In addition, whole areas were devoted to the deportation of Jews and others the Germans considered undesirable, as well as to individuals and institutions that harbored and hid potential deportees. For example, a group of nuns ran a girls' school, at which many Jewish girls lived and attended openly under false names and identities cooked up by the nuns.

The museum was excellent, and it allowed photography, but although I took many photographs, they were mainly of text that I didn't have time to read all of or thought I would have trouble remembering. It presented a huge amount of information on the Resistance in the mountainous Grenoble region, including photos and life stories of many, many individual resistance fighters, their weaponry and strategies, and even a large relief map showing the locations of major Resistance camps and instances of the fighers' actions, divided up by category—you could press a button to light up all the cases of direct confrontation with enemy troops, all the cases of sabotage, all the assassinations, etc. In addition, whole areas were devoted to the deportation of Jews and others the Germans considered undesirable, as well as to individuals and institutions that harbored and hid potential deportees. For example, a group of nuns ran a girls' school, at which many Jewish girls lived and attended openly under false names and identities cooked up by the nuns.

Dinner was at Fantin Latour, the highest ranked restaurant so far on the trip at four Gault-Millau toques. We never did figure out the connection, if any, of the restaurant with the painter of the same name (Henri Fantin-Latour, 1836–1904, of whose work I'm very fond; he did wonderful floral still lives). The artist was born in Grenoble, although nobody seems willing to say just where, and the door to the restaurant (behind David in the left-hand photo) says "Fantin Museum" over it, though I've found no explanation anywhere of what that has to do with either the painter or the restaurant. None of the restaurant's decor involved the artist's work.

Dinner was at Fantin Latour, the highest ranked restaurant so far on the trip at four Gault-Millau toques. We never did figure out the connection, if any, of the restaurant with the painter of the same name (Henri Fantin-Latour, 1836–1904, of whose work I'm very fond; he did wonderful floral still lives). The artist was born in Grenoble, although nobody seems willing to say just where, and the door to the restaurant (behind David in the left-hand photo) says "Fantin Museum" over it, though I've found no explanation anywhere of what that has to do with either the painter or the restaurant. None of the restaurant's decor involved the artist's work.

From the time she first seated us, our waitress told us proudly that tonight we would eat plants. The chef believed strongly in eating plants and went so far as to collected them himself, both in the wild and from those he had transplanted to his garden. The table was even provided with a small handmade booklet, tied together with a ribbon, that included photos and descriptions of "The plants used by the chef."

From the time she first seated us, our waitress told us proudly that tonight we would eat plants. The chef believed strongly in eating plants and went so far as to collected them himself, both in the wild and from those he had transplanted to his garden. The table was even provided with a small handmade booklet, tied together with a ribbon, that included photos and descriptions of "The plants used by the chef."

The second course was a "melting risotto of amaranth" surrounded by "crispy spring vegetables" and "aromatic herbs from the garden." It was beautiful, and tasty too. The risotto was so melting that the tiny amaranth seeds settled into a single layer in the center of the plate, and their foamy yellow sauce rose to the surface to hide them completely. The waitress specified that we need not feel obliged to eat the pea pod. The peas inside were delicious, and as a small gesture of defiance, I ate part of the inner lining of the pod, too. The brown-topped ring-shaped objects around the top of the plate were intriguing. The chef had cut an inch-long section from some sort of green onion or leek stem and charred one end of it, then separated the it into cylinders and stood them charred-end-up on the plate. Yummy.

The second course was a "melting risotto of amaranth" surrounded by "crispy spring vegetables" and "aromatic herbs from the garden." It was beautiful, and tasty too. The risotto was so melting that the tiny amaranth seeds settled into a single layer in the center of the plate, and their foamy yellow sauce rose to the surface to hide them completely. The waitress specified that we need not feel obliged to eat the pea pod. The peas inside were delicious, and as a small gesture of defiance, I ate part of the inner lining of the pod, too. The brown-topped ring-shaped objects around the top of the plate were intriguing. The chef had cut an inch-long section from some sort of green onion or leek stem and charred one end of it, then separated the it into cylinders and stood them charred-end-up on the plate. Yummy.

The menu listed St. Pierre (Zeus faber) as the fish course, but apparently the market let the kitchen down, and they had substituted swordfish (Xiphias gladius). It arrived on a slab of slate and a rock. The slate served as the plate, the rock, heated to a blazing temperature, was set on it, and the chunk of swordfish was slapped on top of that, where it sizzled loudly all the way to the table, then topped with some cooked vegetables (not, apparently, plants). It had been marinated in an infusion of "wild absinthe," by which I assume the chef meant wormwood, Artemisia absinthium, and was garnished with a sprig of the fresh plant, which the waitress advised us not to eat, as it would be very bitter. The fish was delicious—you don't often get swordfish that, despite a nicely crisped finish on the underside, hasn't been overcooked. The rock was still too hot to touch comfortably when we finished and they took it away.

The menu listed St. Pierre (Zeus faber) as the fish course, but apparently the market let the kitchen down, and they had substituted swordfish (Xiphias gladius). It arrived on a slab of slate and a rock. The slate served as the plate, the rock, heated to a blazing temperature, was set on it, and the chunk of swordfish was slapped on top of that, where it sizzled loudly all the way to the table, then topped with some cooked vegetables (not, apparently, plants). It had been marinated in an infusion of "wild absinthe," by which I assume the chef meant wormwood, Artemisia absinthium, and was garnished with a sprig of the fresh plant, which the waitress advised us not to eat, as it would be very bitter. The fish was delicious—you don't often get swordfish that, despite a nicely crisped finish on the underside, hasn't been overcooked. The rock was still too hot to touch comfortably when we finished and they took it away.

Before the meat course, we were served a palate-cleanser—a three-layered juice and sherbet concoction of orange.

Before the meat course, we were served a palate-cleanser—a three-layered juice and sherbet concoction of orange.

My meat course was quail "perfumed with catnip" accompanied by a pool of thick, sweet beet-root sauce. Very good. Both meat courses came with a cooked baby carrot, a heap of sweet and sour shredded cabbage, and some red quinoa. I'm not sure what the greenish puree under David's other vegetables was—perhaps potato.

My meat course was quail "perfumed with catnip" accompanied by a pool of thick, sweet beet-root sauce. Very good. Both meat courses came with a cooked baby carrot, a heap of sweet and sour shredded cabbage, and some red quinoa. I'm not sure what the greenish puree under David's other vegetables was—perhaps potato.

David's dessert was a small disk of intense chocolate cream topped with a little quenelle of ice cream and a few almonds in crisp caramel shells.

David's dessert was a small disk of intense chocolate cream topped with a little quenelle of ice cream and a few almonds in crisp caramel shells.