Wednesday, 13 July 2016, Touring and museuming in Grenoble

Written 1 August 2016

This was our first Ibis hotel of the trip. As recently as 2012, I noted in my diaries that full Ibises provided a much more extensive breakfast buffet than, say "Ibis Budget," which was pretty much croissants and coffee, butter and jam, and sometimes Nutella. For example, the one in Le Havre (6/15/12) included several kinds of breakfast pastries and bread, four kinds of cake, several named kinds of slice-it-yourself cheese, and Spanish potato tortilla. Everything was labeled with little signs saying, e.g., "high fiber," "slow sugars," "fast sugars," and "low carbs."

This year, though, many economies were in evidence. Signs were everywhere in the rooms and lobby advertizing "New! Breakfast just like at the market! Come and feast!," but the buffet was down to the basics. No more cake, no more tortillas, only unlabeled presliced cheese, and signage limited to short bits of hype ending in exclamation points. They've changed to a design of coffee cup that uses no saucer (half the dishes to do). In the rooms, we got only tubes of shower and sink gel hanging from the wall (no more little bars of soap); each room got exactly two bath towels (no hand towels or wash cloths); just one waste basket (rather than one in the room and one in the bathroom); and AC that wouldn't bring the room temperature below 74°F—all features of the Ibis Budget of four years ago. Most ingenious of all, on the joystick operating the faucet in the sink, cold and hot were rotated 90°, so that, if you just flipped the lever straight up to wash your hands, you got only cold water. If you wanted hot, you had to rotate it all the way to the left—a very clever way of economizing on hot water when the user didn't really care about temperature but just wanted some quick water.

On our way to and from the previous day's museum, we had spotted the Office de Tourisme, the the first order of the day was to walk over there first thing to ask about walking tours. Happily, one was scheduled for 10:30 a.m. that very day.

The rain had let up by then, so we accordingly presented ourselves and set out on an excellent two-hour hike through the old city.

A settlement has occupied the site, at the confluence of the Drac and Isère rivers, for several thousand years. The first written record of it is from the 1st century BC, when a Roman officer arrived, with his troops, in the little Gallic village called Cularo.

A settlement has occupied the site, at the confluence of the Drac and Isère rivers, for several thousand years. The first written record of it is from the 1st century BC, when a Roman officer arrived, with his troops, in the little Gallic village called Cularo.

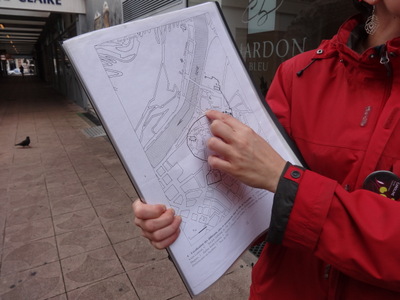

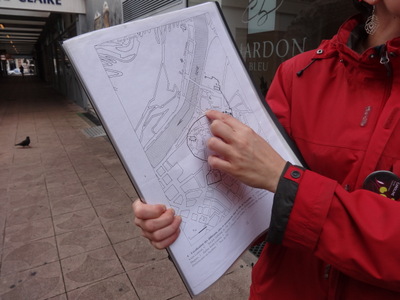

In the 3rd century AD, the Romans built a good solid stone wall around it for defensive purposes. In the left-hand photo, that wall is the almost circular enclosure mostly hidden behind the guide's hand. The river is the Isère, which flows to the left and continues to curve around the mountain across from the city until is merges with the Drac, flowing in from the lower left. The right-hand photo shows a surviving corner tower of that original Roman wall. At the top left, you can see a section of the pick-stuccoed appartment building built directly on top of part of the wall. I don't know whether the taggers who painted on the blank wall above the tower voluntarily respect the ancient wall and keep their paint off it—surely the ancient wall can't be pressure-washed without damage. Maybe the penalties for marking it up are enough worse than those for painting ordinary walls that they are discouraged.

The extension of the wall that branches off near the guide's index finger and extends to the edge of the river farther upstream was added later.

In the 4th century AD, the emperor Gratian visited Cularo and like it so well he made it a Roman city. In gratitude, the populace renamed it Gratianopolis, which, several corruptions later, became "Grenoble." Originally the city was part of the area administered by Vienne (the one south of Lyon that we visited in June of 2011, not Vienna, Austria, which is also called "Vienne" in French), but that area was later split up into areas governed by Vienne, Grenoble, and Geneva.

The site of Roman hot baths may have been discovered behind a section of surviving Roman wall, but they can't be sure yet.

Until recently, Grenoble was plagued with floods; its rivers were called "The Snake" (the widely meandering Isère) and "The Dragon" (the larger and more forthright Drac). The worst was the "cru du lac St. Laurent"; in 1188 AD or so, a natural landslide dammed the Drac and created a good-sized lake, the Lac St. Laurent. Then, 28 years later, in 1216 AD, that dam abruptly collapsed, precipitating the lake's entire contents down the Drac and into the suburbs of the city. Because the Drac was at that point entirely full to overflowing, the Isère had no place to go, backed up, and catastrophically flooded the whole city.

Until recently, Grenoble was plagued with floods; its rivers were called "The Snake" (the widely meandering Isère) and "The Dragon" (the larger and more forthright Drac). The worst was the "cru du lac St. Laurent"; in 1188 AD or so, a natural landslide dammed the Drac and created a good-sized lake, the Lac St. Laurent. Then, 28 years later, in 1216 AD, that dam abruptly collapsed, precipitating the lake's entire contents down the Drac and into the suburbs of the city. Because the Drac was at that point entirely full to overflowing, the Isère had no place to go, backed up, and catastrophically flooded the whole city.

In 1650 a particularly bad flood swept away the tower from the (only) bridge. The last big one was in 1959; after that the rivers were finally brought under control. In the left-hand photo, the guide indicates a high-water marker on a street corner, though I didn't catch which flood it was from.

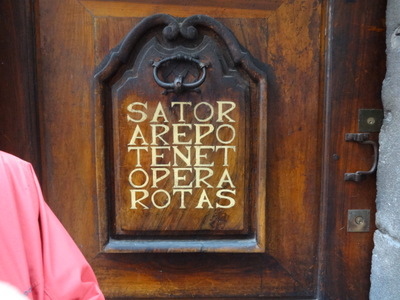

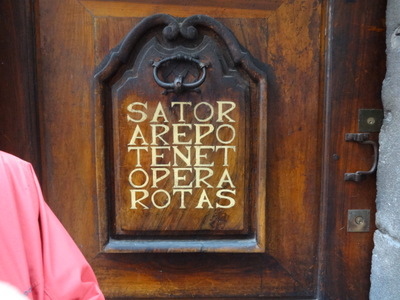

The right-hand photo shows a panel on a door bearing the "Sator square," a famous Latin palindrome that reads the same up, down, forward, back, etc. (its earliest documented appearance was in Pompeii) Its actual translation is a matter of some debate but is something trivial like "The farmer tills his fields." Christianity arrived in Grenoble in the 4th century AD, and the Sator square was supposedly used by Christians to recognize each other before it was okay to be Christianmdash;the letters can be rearranged to spell "pater noster" vertically and horizontally (crossing at the "n"), with a couple of a's and a couple of o's left over to represent "alpha and omega."

Pretty quickly, though, the church established itself as a major power, equal to the nobility. Later, when the parliament, representing the common people, was added, the city's coat of arms became three roses, representing the nobles, the church, and the parliament, what the French call the "three orders." Each of the three orders had its own traditional center; the nobility considered the Place St. André their epicenter, the church had the Place Notre Dame, and the people had the Place aux Herbes (the vegetable market; a small covered pavilion still hosts a weekly vegetable market there).

Pretty quickly, though, the church established itself as a major power, equal to the nobility. Later, when the parliament, representing the common people, was added, the city's coat of arms became three roses, representing the nobles, the church, and the parliament, what the French call the "three orders." Each of the three orders had its own traditional center; the nobility considered the Place St. André their epicenter, the church had the Place Notre Dame, and the people had the Place aux Herbes (the vegetable market; a small covered pavilion still hosts a weekly vegetable market there).

At the left, you can see, outlined on the street and sidewalk in white stone, the site of the first Christian baptistry.

The photo at the right shows some architectural traces from the city's early history, incorporated into a wall with modern windows.

Apparently, aside from the traces the guide showed us, very little remains from the ancient or medieval periods of the city. Most of its architecture is from the 16th century onward. This imposing "tourelle," a sort of bay window protruding over the street, once sheltered a public well. Now, a 200-year-old bookstore occupies the space below it.

Apparently, aside from the traces the guide showed us, very little remains from the ancient or medieval periods of the city. Most of its architecture is from the 16th century onward. This imposing "tourelle," a sort of bay window protruding over the street, once sheltered a public well. Now, a 200-year-old bookstore occupies the space below it.

The guide emphasized that, in Grenoble, the nobility did not bother to flaunt its wealth and power on the outside of its houses. Unlike the bourgeoisie of, say, Bordeaux, which had gone off to the colonies, come back "nouveau riche," and built showy mansions, that of Grenoble had stayed at home and remained prosperous but not wealthy, so the nobility didn't have to "keep up with them," as it were.

The photo at the right shows a monumental 19th-century statue of Bayard, the original "knight without fear and above reproach," who was apparently from Grenoble. He fought with François I in Italy in the 16th century.

In the 16th century, under Henri IV, a nobleman with a very long name but who was commonly referred to as Lesdiguières (the guide displays his likeness at the left) was placed in charge of the city. He's he one who built he extension of the city wall visible in the first photo above. Knowing he wasn't especially popular with the locals (he was protestant, and they were Catholic; when the king sent him, he had to fight his way in), he equipped it with a fortified tower at the end in which he and his guards could take refuge if necessary. Later in Grenoble's history, that tower because a military pigeon-cote and housed hundreds of birds. One reason Lesdiguières had popularity problems was that he was a protestant, but in the end he converted to Catholicism as a condition of becoming a Maréchal de France.

In the 16th century, under Henri IV, a nobleman with a very long name but who was commonly referred to as Lesdiguières (the guide displays his likeness at the left) was placed in charge of the city. He's he one who built he extension of the city wall visible in the first photo above. Knowing he wasn't especially popular with the locals (he was protestant, and they were Catholic; when the king sent him, he had to fight his way in), he equipped it with a fortified tower at the end in which he and his guards could take refuge if necessary. Later in Grenoble's history, that tower because a military pigeon-cote and housed hundreds of birds. One reason Lesdiguières had popularity problems was that he was a protestant, but in the end he converted to Catholicism as a condition of becoming a Maréchal de France.

The space that his wall extension occupied is now filled by this handsome modern museum of art, which we visited in the afternoon. Portions of the base of his wall are preserved in its basement.

Lesdiguières was a major figure in the history of the city. He's the one who decided the Bastille (the modest fortification on the mountain facing the city across the river) should be more strongly fortified, and he instituted many important public works. Please note that what you're getting here is a very disorganized collection of fragments from the very extensive and informative walking tour. For a more coherent account, you can also address yourself to Wikipedia.

At the right here is the Fountain of Lavallette, which commemorates a 19th-century mayor of the city and is prominently decorated with dolphins—the whole region is known as the "Dauphiné" (hence ravioles du Dauphiné and other such names).

At the right here is the Fountain of Lavallette, which commemorates a 19th-century mayor of the city and is prominently decorated with dolphins—the whole region is known as the "Dauphiné" (hence ravioles du Dauphiné and other such names).

At the right is the entrance to the building where French author and Grenoble native) Stendalh (1783–1842) spent as much time as he could with his grandfather (he was very unhappy at home, under a harsh, strict father after his beloved mother died when he was 7). The Gagnon Apartment is now a museum, and from the back, you can see the second-floor terrace with a trellis of grapes that I'm told is widely known—I'm afraid I haven't read enough of his work to know of it. The trellis is still there and still supports grape vines.

Grenoble is also very proud to be the birthplace of the French Revolution. In 1788, the king's controller-general tried to abolish its parliament so as to impose a new taxation regime. The people were having none of it, so on 7 June of that day, the people took to the rooftops and rained roof tiles down on the king's troops, driving them out of the city. The commander was forced to allow parliament to meet, though in a village nearby rather than in the capital. Nonetheless, the violence continued to escalate and eventually gave rise to the revolution.

Other interesting things we learned during the tour:

In 1880, Grenoble opened France's first chamber of commerce and tourist office. All those Offices de Tourisme we have frequented are its descendents.

- Until World War II, Grenoble held the world monopoly on fine kid-skin gloves. Several of the large factors still stand, but most have been repurposed.

- In the 17th century (still under Lesdiguières), a big extensiuon of the city ramparts brought the grain market within the walls. The word for "grainery" was corrupted to "grenette." The Place Grenette is the large plaza just outside our hotel. After the revolution, the guillotine was placed there, but largely for show. Two refractory priests were the only ones ever executed.

- The city has many specialities feature Chartreuse liqueur and nuts (which are grown in the neighboring countryside). For the 1968 winter Olympics, a local bakery invented a commemorative nut cake, which is still sold one place in the city.

- The distinctive blue-gray stone we saw around the city comes from a particular quarry in the Massif du chartreuse; it resisted flooding well, so it was used especially often on ground floors.

- And finally, what's with all the dolphins? Why is a landlocked region called "le Dauphiné"? Hypotheses differ, but the most commonly held is that a 12th-century ruler of the region encounter dolphins on his way to and from the Crusades and, finding them strong, smart, and loyal, adopted them as his emblem. He took to calling himself "the Dolphin" (le dauphin) rather than "the Count" and made dolphins the symbol of the whole region.

In 1349, the then ruler of the area was in financial trouble and had no direct heir, so he sold the whole area to France. The French king annexed it and essentially gave it to his son to practice on before he took over the throne, and the crown prince of France has been "le dauphin" ever since! I always wondered where that bizarre title came from!

Here are some less consequential (or at least less historic) things we saw as we walked around. These two photos of outstandingly ugly and graffiti-covered derelict buildings on the hillside below the Bastille—in plain view of the whole downtown—are the remnants of an extremely well-thought-of university. When the university moved to shiny new digs on a suburban campus, these buildings were simply abandoned to the attentions of the taggers. We thought they gave a very bad first impression of the city. Apparently plans are afoot to replace them with luxury hotels; I hope they do that soon!

Here are some less consequential (or at least less historic) things we saw as we walked around. These two photos of outstandingly ugly and graffiti-covered derelict buildings on the hillside below the Bastille—in plain view of the whole downtown—are the remnants of an extremely well-thought-of university. When the university moved to shiny new digs on a suburban campus, these buildings were simply abandoned to the attentions of the taggers. We thought they gave a very bad first impression of the city. Apparently plans are afoot to replace them with luxury hotels; I hope they do that soon!

A charming item we walked by many times in the course of our time in Grenoble was this planter, on a table outside a café—a somewhat larger than life-size wicker shoe whose toe was a bit worse for the wear.

A charming item we walked by many times in the course of our time in Grenoble was this planter, on a table outside a café—a somewhat larger than life-size wicker shoe whose toe was a bit worse for the wear.

Something that cracked us up was this sidewalk sign for a new food item—the sign says, "A savory pause? Try the lunchwaf!" It seemed to be a sandwich made of arugula, tomatoes, and cheese between two waffles, I couldn't tell whether it was baked as one piece with the filling in place or assembled after the waffles were made.

On another street, school children were meticulously painting what started out to be ordinary, black iron bollards intended to protect pedestrians from passing cars. Something had been affixed to the bollards to provide the relief you see in the shapes of the beards and arms.

On another street, school children were meticulously painting what started out to be ordinary, black iron bollards intended to protect pedestrians from passing cars. Something had been affixed to the bollards to provide the relief you see in the shapes of the beards and arms.

I only noticed later that the right-hand photo shows some of the children at work. I can't tell whether that's a reflection in the shop window or a photo someone has posted behind it of a previous work session. The results were charming; each bollard was different.

Finally, on the way back from the tour, whichi ended at 12:30 p.m., we passed the entrance of the imposing covered city market (19th century, I think, from all the wrought iron overhead), the Halles Ste. Claire. It was late for it still to be open, but I just had to look in.

Most stalls were in the process of closing and cleaning up, but a few still had food on display. At the left here are hams of several kinds, assorted sausages, and pâtés "en croute" (i.e., baked in pastry cases).

Finally, on the way back from the tour, whichi ended at 12:30 p.m., we passed the entrance of the imposing covered city market (19th century, I think, from all the wrought iron overhead), the Halles Ste. Claire. It was late for it still to be open, but I just had to look in.

Most stalls were in the process of closing and cleaning up, but a few still had food on display. At the left here are hams of several kinds, assorted sausages, and pâtés "en croute" (i.e., baked in pastry cases).

A fish display was little picked over but still attractive. They still had some cooked shrimp (both in the shell and shelled), fresh and smoked filets of haddock, stone-crab claws, and small boiled whelks.

A fish display was little picked over but still attractive. They still had some cooked shrimp (both in the shell and shelled), fresh and smoked filets of haddock, stone-crab claws, and small boiled whelks.

In the other half of the case were whole fish, cooked and fresh prawns, langoustines, and some filets of fish. I could make out sea bream, a good-sized flatfish, some sardines, some little red mullet, one eel, and a few oranges decoratively studded with cloves.

By this time, we were thoroughly hungry, so we headed back to the Place Grenette and settled at a place that called itself "Le Sporting." David ordered the salade de chevre chaud, which included lettuce, tomato, fried potatoes, lardons, and a slice of toast with grilled goat cheese on top, plus two decorative sprigs of Belgian endive.

By this time, we were thoroughly hungry, so we headed back to the Place Grenette and settled at a place that called itself "Le Sporting." David ordered the salade de chevre chaud, which included lettuce, tomato, fried potatoes, lardons, and a slice of toast with grilled goat cheese on top, plus two decorative sprigs of Belgian endive.

I chose (as I almost always do, given the chance) the salade Perigourdine, which started with the same lettuce, tomatoes, and endive but wa topped with a slice of foie gras, toast, and grilled slices of fresh duck breast. I can only conclude that the heart next to its entry on the menu was a sign of affection and not a token of its cardiac-healthiness.

Both were excellent except for one thing—neither one included a trace of salad dressing. We finally snagged a passing waiter and asked for at least oil and vinegar. He came back with two dishes of mustard vinaigrette, which were probably intended to have been poured over the salad before it came to the table.

Then we were off to the museum of art for the afternoon, as it looked like rain and the Bastille was still fogged in. The building is entered this way, at the far end from the view given above. It does have a wheelchair entrance, so the disabled need not really face all those stairs. Note the large pink mimosa in bloom out front.

Then we were off to the museum of art for the afternoon, as it looked like rain and the Bastille was still fogged in. The building is entered this way, at the far end from the view given above. It does have a wheelchair entrance, so the disabled need not really face all those stairs. Note the large pink mimosa in bloom out front.

Once you're past the lobby, you take a right turn into this huge and magnificent, brightly sun-lit hallway that runs from the front of the building to the back. All the main-floor galleries open off it, mostly to the left as viewed from the front of the building. That design made it very easy both to work your way systematically through the collection chronologically and to "skip around" by returning to the hallway and moving down to the era you wanted.

One of the first things we encountered was this 16th-century anonymous Hercules.

One of the first things we encountered was this 16th-century anonymous Hercules.

Farther along, we came to Champollion (Bartholdi, 1867), child prodigy, father of Egyptology, and decipherer of the hierglyphic system, standing thoughtfully with his foot on the broken head of some monumental ancient Egyptian statue. Fun.

The collection was very large. We came to works by Rubens, Canalleto, Jacques-Louis David, Ingres, Andy Warhol, and Alexander Calder, as well as many more less well known to us. In addition, I saw quite a number of striking works listed as anonymous, more than one usually sees in a large museum.

Two more works that particularly caught my eye were this still life and the one in the photo at the right, entitled "Homer."

Two more works that particularly caught my eye were this still life and the one in the photo at the right, entitled "Homer."

The still life is by Jan Davidsz de Heem, painter of the magnificent prominently featured in the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota. We love that one and have a full-size poster of it hanging in our house this minute.

The other depicts blind Homer in the center panel, his listener/disciple/follower asleep at his side and his begging bowl at his knee, declaiming nonetheless. The panel at the left is of Penelope waiting for Odysseus, and that at the right a tragic scene from the Illiad.

I also especially liked a medieval wooden figure of St. Florian, patron saint of firefighters, emptying a bucket of water over a flaming building that comes up about to his knee; a moody painting of a purple-robed figure sitting at a desk in a cluttered study, labeled "Gutenberg inventing printing"; and a small section of work by Henri Fantin-Latour and his wife, Victoria Dubourg—two of her beautiful kitchen still lives, his portrait of her, and his famous self-portrait as a young man.

Once we'd looked at everything, including the old city wall in the basement, we walked back to our hotel to rest our weary feet for a while before dinner, which as it happened was in a restaurant right across from the museum, so we retraced our steps to get there.

Here I am, outside the restaurant, called "L'Escalier," "The Staircase," because it's located a little below present street level right next to the old stone staircase leading up to the level at which the art museum rests.

Here I am, outside the restaurant, called "L'Escalier," "The Staircase," because it's located a little below present street level right next to the old stone staircase leading up to the level at which the art museum rests.

We were greated enthusiastically at the door by the proprietor, who I think is also the chef, dressed in a red checked shirt and jeans. He seemed to spend most of the evening greeting guests, in the dining room, or answering the restaurant's phone.

Above our table was this framed model of the restaurant's façade, without the awning or the shrubbery.

We chose the "Menu Gourmet," and I resolutely ignored the corresponding "Menu Gourmette," billed as a lo-cal version for the ladies. I was pretty shocked when a lady at a nearby table ordered it!

We chose the "Menu Gourmet," and I resolutely ignored the corresponding "Menu Gourmette," billed as a lo-cal version for the ladies. I was pretty shocked when a lady at a nearby table ordered it!

We were tempted by the "spoon menu," in which a whole succession of courses each consists of two spoonfuls of the same basic ingredient but in different preparations. Intriguing, but the menu we chose had all the stuff we wanted to eat.

The single waiter was in complete contrast to the relaxed and informal chef. He was slender, graceful, impeccably dressed, fast, and amazingly skillful and professional.

Our first course was a hen's egg, served softly scrambled, in a neatly decapitated eggshell nestled in a silver egg cup that mimicked half a shattered eggshell resting on three tiny silver dolphins, topped with mujjöl caviar. Never heard of that caviar before, but it was delicious!

Spoons were a major theme of the restaurant. The napkin rings were bent silver spoons. The design on the china was spoons with handles in the shape of ginkgo leaves, the spoon menu, and here, at left, is the salt and pepper service. The tiny spoon (the ginkgo-leaf handle) lying across the bowls of the two crossed spoons is loose and can be lifted and used to spoon salt or pepper, but the rest is welded together, crossed spoons, tiny silver cups, and all.

Spoons were a major theme of the restaurant. The napkin rings were bent silver spoons. The design on the china was spoons with handles in the shape of ginkgo leaves, the spoon menu, and here, at left, is the salt and pepper service. The tiny spoon (the ginkgo-leaf handle) lying across the bowls of the two crossed spoons is loose and can be lifted and used to spoon salt or pepper, but the rest is welded together, crossed spoons, tiny silver cups, and all.

The first second course was foie grass prepared two ways: one rolled with dried spiced beef and the other with Szechuan pepper. The orange-colored quenelle is a coarse purée of melon with balsamic vinegar, adn the leaf-shaped object above it is a thin sheet of something (rice paper) with black sesame seeds embedded in it.

After that came crispy-skinned filet of daurade (Sparus aurata) on a "cloud of green tea" accompanied by a shredded apple and celery root rolled up in nori. Another excellent dish.

After that came crispy-skinned filet of daurade (Sparus aurata) on a "cloud of green tea" accompanied by a shredded apple and celery root rolled up in nori. Another excellent dish.

The meat course was rack of lamb under a crust of crumbs and herbes de Provence. On the side, a braised artichoke heart. This dish didn't work as well. The lamb itself was excellent, but the crumb "crust" was actually pasty and unappetizing. The artichoke was tasty but not trimmed closely enough— the upper leaves were way too chewy. Probably the best part of the dish was the pair of little individual hibachis—you can see them between my plate and David's—on each of which half a lamb kidney was sizzling over a tea light. Those were yummy, tender and still pink inside. David gave me his (his loss).

The cheese course was truffled Carré de Trièves, and we found it a bit much. Each serving was a square cut from a cheese (itself already square), sliced in two edgewise, and sandwiched with a layer of minced black truffle. It was good for the first bite or two, and the truffle definitely had flavor, but finishing it was hard going. First, it was a little too cold, which made it stiff, and it was really rich. Not a bad cheese course, but I would serve a piece half the size.

The cheese course was truffled Carré de Trièves, and we found it a bit much. Each serving was a square cut from a cheese (itself already square), sliced in two edgewise, and sandwiched with a layer of minced black truffle. It was good for the first bite or two, and the truffle definitely had flavor, but finishing it was hard going. First, it was a little too cold, which made it stiff, and it was really rich. Not a bad cheese course, but I would serve a piece half the size.

Dessert was a cylinder of chocolate granache on a crispy base and topped with a sheet of crisp caramel. On the side was a mojito granité, i.e., a coarse sorbet, with a fat straw for sipping. The mojito was too alcoholic for me, but the chocolate was good, and I'm not usually fond of rich chocolate desserts at the ends of big meals.

Throughout, the waiter was a marvel. Every table got swift and attentive service, we never had a lag between courses, he was everywhere at once, effortlessly and in silence. And he never, ever asked us how we were doing or whether we liked the food—very restful after the last couple of years' constant barrage of "Ça a été?" and "Ça vous a plu?"

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

A settlement has occupied the site, at the confluence of the Drac and Isère rivers, for several thousand years. The first written record of it is from the 1st century BC, when a Roman officer arrived, with his troops, in the little Gallic village called Cularo.

A settlement has occupied the site, at the confluence of the Drac and Isère rivers, for several thousand years. The first written record of it is from the 1st century BC, when a Roman officer arrived, with his troops, in the little Gallic village called Cularo.

Until recently, Grenoble was plagued with floods; its rivers were called "The Snake" (the widely meandering Isère) and "The Dragon" (the larger and more forthright Drac). The worst was the "cru du lac St. Laurent"; in 1188 AD or so, a natural landslide dammed the Drac and created a good-sized lake, the Lac St. Laurent. Then, 28 years later, in 1216 AD, that dam abruptly collapsed, precipitating the lake's entire contents down the Drac and into the suburbs of the city. Because the Drac was at that point entirely full to overflowing, the Isère had no place to go, backed up, and catastrophically flooded the whole city.

Until recently, Grenoble was plagued with floods; its rivers were called "The Snake" (the widely meandering Isère) and "The Dragon" (the larger and more forthright Drac). The worst was the "cru du lac St. Laurent"; in 1188 AD or so, a natural landslide dammed the Drac and created a good-sized lake, the Lac St. Laurent. Then, 28 years later, in 1216 AD, that dam abruptly collapsed, precipitating the lake's entire contents down the Drac and into the suburbs of the city. Because the Drac was at that point entirely full to overflowing, the Isère had no place to go, backed up, and catastrophically flooded the whole city.

Pretty quickly, though, the church established itself as a major power, equal to the nobility. Later, when the parliament, representing the common people, was added, the city's coat of arms became three roses, representing the nobles, the church, and the parliament, what the French call the "three orders." Each of the three orders had its own traditional center; the nobility considered the Place St. André their epicenter, the church had the Place Notre Dame, and the people had the Place aux Herbes (the vegetable market; a small covered pavilion still hosts a weekly vegetable market there).

Pretty quickly, though, the church established itself as a major power, equal to the nobility. Later, when the parliament, representing the common people, was added, the city's coat of arms became three roses, representing the nobles, the church, and the parliament, what the French call the "three orders." Each of the three orders had its own traditional center; the nobility considered the Place St. André their epicenter, the church had the Place Notre Dame, and the people had the Place aux Herbes (the vegetable market; a small covered pavilion still hosts a weekly vegetable market there).

Apparently, aside from the traces the guide showed us, very little remains from the ancient or medieval periods of the city. Most of its architecture is from the 16th century onward. This imposing "tourelle," a sort of bay window protruding over the street, once sheltered a public well. Now, a 200-year-old bookstore occupies the space below it.

Apparently, aside from the traces the guide showed us, very little remains from the ancient or medieval periods of the city. Most of its architecture is from the 16th century onward. This imposing "tourelle," a sort of bay window protruding over the street, once sheltered a public well. Now, a 200-year-old bookstore occupies the space below it.

In the 16th century, under Henri IV, a nobleman with a very long name but who was commonly referred to as Lesdiguières (the guide displays his likeness at the left) was placed in charge of the city. He's he one who built he extension of the city wall visible in the first photo above. Knowing he wasn't especially popular with the locals (he was protestant, and they were Catholic; when the king sent him, he had to fight his way in), he equipped it with a fortified tower at the end in which he and his guards could take refuge if necessary. Later in Grenoble's history, that tower because a military pigeon-cote and housed hundreds of birds. One reason Lesdiguières had popularity problems was that he was a protestant, but in the end he converted to Catholicism as a condition of becoming a Maréchal de France.

In the 16th century, under Henri IV, a nobleman with a very long name but who was commonly referred to as Lesdiguières (the guide displays his likeness at the left) was placed in charge of the city. He's he one who built he extension of the city wall visible in the first photo above. Knowing he wasn't especially popular with the locals (he was protestant, and they were Catholic; when the king sent him, he had to fight his way in), he equipped it with a fortified tower at the end in which he and his guards could take refuge if necessary. Later in Grenoble's history, that tower because a military pigeon-cote and housed hundreds of birds. One reason Lesdiguières had popularity problems was that he was a protestant, but in the end he converted to Catholicism as a condition of becoming a Maréchal de France.

At the right here is the Fountain of Lavallette, which commemorates a 19th-century mayor of the city and is prominently decorated with dolphins—the whole region is known as the "Dauphiné" (hence ravioles du Dauphiné and other such names).

At the right here is the Fountain of Lavallette, which commemorates a 19th-century mayor of the city and is prominently decorated with dolphins—the whole region is known as the "Dauphiné" (hence ravioles du Dauphiné and other such names).

Here are some less consequential (or at least less historic) things we saw as we walked around. These two photos of outstandingly ugly and graffiti-covered derelict buildings on the hillside below the Bastille—in plain view of the whole downtown—are the remnants of an extremely well-thought-of university. When the university moved to shiny new digs on a suburban campus, these buildings were simply abandoned to the attentions of the taggers. We thought they gave a very bad first impression of the city. Apparently plans are afoot to replace them with luxury hotels; I hope they do that soon!

Here are some less consequential (or at least less historic) things we saw as we walked around. These two photos of outstandingly ugly and graffiti-covered derelict buildings on the hillside below the Bastille—in plain view of the whole downtown—are the remnants of an extremely well-thought-of university. When the university moved to shiny new digs on a suburban campus, these buildings were simply abandoned to the attentions of the taggers. We thought they gave a very bad first impression of the city. Apparently plans are afoot to replace them with luxury hotels; I hope they do that soon!

A charming item we walked by many times in the course of our time in Grenoble was this planter, on a table outside a café—a somewhat larger than life-size wicker shoe whose toe was a bit worse for the wear.

A charming item we walked by many times in the course of our time in Grenoble was this planter, on a table outside a café—a somewhat larger than life-size wicker shoe whose toe was a bit worse for the wear.

On another street, school children were meticulously painting what started out to be ordinary, black iron bollards intended to protect pedestrians from passing cars. Something had been affixed to the bollards to provide the relief you see in the shapes of the beards and arms.

On another street, school children were meticulously painting what started out to be ordinary, black iron bollards intended to protect pedestrians from passing cars. Something had been affixed to the bollards to provide the relief you see in the shapes of the beards and arms.

Finally, on the way back from the tour, whichi ended at 12:30 p.m., we passed the entrance of the imposing covered city market (19th century, I think, from all the wrought iron overhead), the Halles Ste. Claire. It was late for it still to be open, but I just had to look in.

Most stalls were in the process of closing and cleaning up, but a few still had food on display. At the left here are hams of several kinds, assorted sausages, and pâtés "en croute" (i.e., baked in pastry cases).

Finally, on the way back from the tour, whichi ended at 12:30 p.m., we passed the entrance of the imposing covered city market (19th century, I think, from all the wrought iron overhead), the Halles Ste. Claire. It was late for it still to be open, but I just had to look in.

Most stalls were in the process of closing and cleaning up, but a few still had food on display. At the left here are hams of several kinds, assorted sausages, and pâtés "en croute" (i.e., baked in pastry cases).

A fish display was little picked over but still attractive. They still had some cooked shrimp (both in the shell and shelled), fresh and smoked filets of haddock, stone-crab claws, and small boiled whelks.

A fish display was little picked over but still attractive. They still had some cooked shrimp (both in the shell and shelled), fresh and smoked filets of haddock, stone-crab claws, and small boiled whelks.

By this time, we were thoroughly hungry, so we headed back to the Place Grenette and settled at a place that called itself "Le Sporting." David ordered the salade de chevre chaud, which included lettuce, tomato, fried potatoes, lardons, and a slice of toast with grilled goat cheese on top, plus two decorative sprigs of Belgian endive.

By this time, we were thoroughly hungry, so we headed back to the Place Grenette and settled at a place that called itself "Le Sporting." David ordered the salade de chevre chaud, which included lettuce, tomato, fried potatoes, lardons, and a slice of toast with grilled goat cheese on top, plus two decorative sprigs of Belgian endive.

Then we were off to the museum of art for the afternoon, as it looked like rain and the Bastille was still fogged in. The building is entered this way, at the far end from the view given above. It does have a wheelchair entrance, so the disabled need not really face all those stairs. Note the large pink mimosa in bloom out front.

Then we were off to the museum of art for the afternoon, as it looked like rain and the Bastille was still fogged in. The building is entered this way, at the far end from the view given above. It does have a wheelchair entrance, so the disabled need not really face all those stairs. Note the large pink mimosa in bloom out front.

One of the first things we encountered was this 16th-century anonymous Hercules.

One of the first things we encountered was this 16th-century anonymous Hercules.

Two more works that particularly caught my eye were this still life and the one in the photo at the right, entitled "Homer."

Two more works that particularly caught my eye were this still life and the one in the photo at the right, entitled "Homer."

Here I am, outside the restaurant, called "L'Escalier," "The Staircase," because it's located a little below present street level right next to the old stone staircase leading up to the level at which the art museum rests.

Here I am, outside the restaurant, called "L'Escalier," "The Staircase," because it's located a little below present street level right next to the old stone staircase leading up to the level at which the art museum rests.

We chose the "Menu Gourmet," and I resolutely ignored the corresponding "Menu Gourmette," billed as a lo-cal version for the ladies. I was pretty shocked when a lady at a nearby table ordered it!

We chose the "Menu Gourmet," and I resolutely ignored the corresponding "Menu Gourmette," billed as a lo-cal version for the ladies. I was pretty shocked when a lady at a nearby table ordered it!

Spoons were a major theme of the restaurant. The napkin rings were bent silver spoons. The design on the china was spoons with handles in the shape of ginkgo leaves, the spoon menu, and here, at left, is the salt and pepper service. The tiny spoon (the ginkgo-leaf handle) lying across the bowls of the two crossed spoons is loose and can be lifted and used to spoon salt or pepper, but the rest is welded together, crossed spoons, tiny silver cups, and all.

Spoons were a major theme of the restaurant. The napkin rings were bent silver spoons. The design on the china was spoons with handles in the shape of ginkgo leaves, the spoon menu, and here, at left, is the salt and pepper service. The tiny spoon (the ginkgo-leaf handle) lying across the bowls of the two crossed spoons is loose and can be lifted and used to spoon salt or pepper, but the rest is welded together, crossed spoons, tiny silver cups, and all.

After that came crispy-skinned filet of daurade (Sparus aurata) on a "cloud of green tea" accompanied by a shredded apple and celery root rolled up in nori. Another excellent dish.

After that came crispy-skinned filet of daurade (Sparus aurata) on a "cloud of green tea" accompanied by a shredded apple and celery root rolled up in nori. Another excellent dish.

The cheese course was truffled Carré de Trièves, and we found it a bit much. Each serving was a square cut from a cheese (itself already square), sliced in two edgewise, and sandwiched with a layer of minced black truffle. It was good for the first bite or two, and the truffle definitely had flavor, but finishing it was hard going. First, it was a little too cold, which made it stiff, and it was really rich. Not a bad cheese course, but I would serve a piece half the size.

The cheese course was truffled Carré de Trièves, and we found it a bit much. Each serving was a square cut from a cheese (itself already square), sliced in two edgewise, and sandwiched with a layer of minced black truffle. It was good for the first bite or two, and the truffle definitely had flavor, but finishing it was hard going. First, it was a little too cold, which made it stiff, and it was really rich. Not a bad cheese course, but I would serve a piece half the size.