Friday, 28 June, Mainz and a Taste of Germany

Written 8 August 2019

The Kvasir docked in Mainz during the on-board concert on Thursday evening, and the evening's briefing presented cruel choices. Friday morning, we could go on the included city walking tour, which included the cathedral and the Gutenberg museum and demonstration of Gutenberg printing technology. Or we could join the simultaneous optional walking tour of historic Mainz and St. Stephens's church to see yet more Chagall windows. Or we could go off on our own to see the Museum of Ancient Seafaring, which displayed nine 4th-century Roman ships made of German oak that were found buried in clay during construction of a riverside hotel. Drat. In the end, we went for the Gutenberg—I had always wanted to see that. But I was really sorry to miss the Roman ships.

The Kvasir docked in Mainz during the on-board concert on Thursday evening, and the evening's briefing presented cruel choices. Friday morning, we could go on the included city walking tour, which included the cathedral and the Gutenberg museum and demonstration of Gutenberg printing technology. Or we could join the simultaneous optional walking tour of historic Mainz and St. Stephens's church to see yet more Chagall windows. Or we could go off on our own to see the Museum of Ancient Seafaring, which displayed nine 4th-century Roman ships made of German oak that were found buried in clay during construction of a riverside hotel. Drat. In the end, we went for the Gutenberg—I had always wanted to see that. But I was really sorry to miss the Roman ships.

So after breakfast, we assembled with group 30H and set off on the city walking tour. Mainz, at 160,000 inhabitants, is quite small but is the capital of the Rhineland Palatinate and the largest city in it. The building at the left here is city hall. It was specifically designed so that parliament sits in the windowless parts of the building, so that representatives are not distracted by the view of the river, which is just out of the picture to the left.

Mainz is also the wine capital of Germany. The country has 13 high-quality wine regions, of which 6 or 7 are in Rhineland Palatinate. The post full of green signs at the right indicates the directions and distances to other great wine capitals of the world.

Our stroll from the ship into the town led us through yet another beautiful allée of sycamores.

Our stroll from the ship into the town led us through yet another beautiful allée of sycamores.

According to our guide, the river used to be much wider. The river was deliberately narrowed, deepened, ad shortened by 70 km (by straightening of bends) in the 1860's. The sycamore allée and the row of handsome 18th and 19th century merchants' mansions "inland" of them are actually on the batture, in area that used to be part of the river. The city was 87% destroyed in WWII, but the mansions were spared.

It also led past this plaque in the sidewalk commemorating the birthplace of Hedwig Reiling (1880–1942). Her daughter Netty Reiling changed her name to Anna Seghers and wrong Das siebte Kreuz (a famous antiwar novel, The Seventh Cross). They were Jewish. Hedwig died in a concentration camp; Anna escaped to the new world.

While we were still by the river, on our stroll, our guide gave us a little history. When territory was divided up after WWII, Mainze and the suburbs on the same side of the river were in the British zone. The areas on the other bank were in Russian, French, and American zones, so places that had once been part of Mainz were separated from it and are now part of Wiesbaden, on the other bank. To mark their origin, though, the ones that used to belong to Mainz prefix their names with "Mainz." For example, the area just at the other end of the Roman bridge is "Mainz-Kastel." The river Main flows into the Rhine at the railway bridge.

The cement factory on the other side of the river also used to belong to Mainz. It produced the cement that was shipped to the U.S. to form the pedestel of the Statue of Liberty.

In Fischtor Square, we passed a pair of these graceful fountains feature large leaping fish. Of course, I asked the guide what kind they were, and of course he said nobody was sure, but some people think they look like salmon, which occurred historically in the river. Salmon? Really? With that long, pointed, bony snout? I think they were pike. I wish I'd gotten a closer photo, but you can Google up a much better image by searching on "Public Fish Fountain on Fischtor Square."

In Fischtor Square, we passed a pair of these graceful fountains feature large leaping fish. Of course, I asked the guide what kind they were, and of course he said nobody was sure, but some people think they look like salmon, which occurred historically in the river. Salmon? Really? With that long, pointed, bony snout? I think they were pike. I wish I'd gotten a closer photo, but you can Google up a much better image by searching on "Public Fish Fountain on Fischtor Square."

The city wall had gates named for the products that entered the city by them: the wood gate, iron gate, wine gate, etc. We entered through the fish gate.

Fish-market Jacob has been in the same family for 130 years. The fish-market tower was torn down in the 1950's, but it's outlined in the sidewalk, so you can tell where it was.

At the right is our first view of Mainz cathedral.

To my delight, a market was in progress in one of the squares we passed throughmdash;it's apparently there every Tuesday, Friday, and Saturday.At the left is a stand selling flavored oils. It's particularly pushing cumin oil, for health.

To my delight, a market was in progress in one of the squares we passed throughmdash;it's apparently there every Tuesday, Friday, and Saturday.At the left is a stand selling flavored oils. It's particularly pushing cumin oil, for health.

At the right is a bread vendor, also emphasizing the heathiness of her wares.

At the left here a pork butcher is selling cooked and raw meat and sausages. The meat is under glass, and the green stuff is just reflections of the foliage of a nearby tree.

At the left here a pork butcher is selling cooked and raw meat and sausages. The meat is under glass, and the green stuff is just reflections of the foliage of a nearby tree.

At the right is a cheese vendor. The cheese in the front row are clearly flavored with addenda, like sage, truffles, seeds, or paprika. I didn't see any labels that would give me a clue.

The vegetables were beautiful. Note the lovely purple cauliflower at the lower left, beside big bundles of fresh mint. Above them are fennel bulbs, speckled and baby fava beans in the shell, English peas, and a big bunch of fresh dill.

The vegetables were beautiful. Note the lovely purple cauliflower at the lower left, beside big bundles of fresh mint. Above them are fennel bulbs, speckled and baby fava beans in the shell, English peas, and a big bunch of fresh dill.

In the photo to the right are bell and long peppers of sevral colors; yellow onions, spring onions, and big red shallots; heads of dark red and white raddichio, and luminously yellow squash blossoms for stuffing. The herbs are flat parsley (lower right) and pots of basil, behind the raddichio.

At the left here are "sweet 100" tomatoes on the vine, "heirloom" tomatoes of funny shapes and colors, ginger root, red and white onions, fat eggplants, and in the center "king eryngii" mushrooms, mostly thick meaty stem.

At the left here are "sweet 100" tomatoes on the vine, "heirloom" tomatoes of funny shapes and colors, ginger root, red and white onions, fat eggplants, and in the center "king eryngii" mushrooms, mostly thick meaty stem.

The strawberries in the right-hand photo don't look quite like the ones in France—they're too pointed.

At the left here is a big bin of chanterelles. The adjacent stall had an even larger crate of them, but they looked less fresh and somewhat dried out. I didn't get a shot showing the prices, so I don't know whether they cost the same.

At the left here is a big bin of chanterelles. The adjacent stall had an even larger crate of them, but they looked less fresh and somewhat dried out. I didn't get a shot showing the prices, so I don't know whether they cost the same.

At the right is part of a large array of fresh herbs in pots, with the German names, legible if I blow the photo up. I'll have to make a list and try to learn them.

This three-columned well was a 16th-century gift from the ruler (prince-elector and cardinal Albert) to his people, whom he had just subdued, to remind them who was boss. I couldn't get all of it into the photo, but it's topped by a tall ornate spire that culminates in a seated bishop with a smaller figure wearing a crown over his head. I'd bet those are Albert and above him God.

This three-columned well was a 16th-century gift from the ruler (prince-elector and cardinal Albert) to his people, whom he had just subdued, to remind them who was boss. I couldn't get all of it into the photo, but it's topped by a tall ornate spire that culminates in a seated bishop with a smaller figure wearing a crown over his head. I'd bet those are Albert and above him God.

Our guide mentioned that many of these "medieval" faccedil;ades are only there for decoration and that the buildings behind them have been completely modernized.

Also in the market square was a memorial post, for victims of WWI. It's a tall, thick wooden post, as big around as a telephone pole but not as tall. Individuals could buy nails to be driven into the post in memory of loved ones who died in the war. Several other cities had them as well, but this is the only one still in its place today.

Written 16 August 2019

The cathedral is an unusual one. It was built as a coronation church, around the year 1000 (dedicated in 1009), and as I understand it, someone stole coronation rights from someone else by building it. It's unusual in that it has an apse and an altar at each end, and stranger still, the main altar (St. Martin's) is the western one. The other end is dedicated to St. Stephen. The main entrance is in the side, between the two.

The cathedral is an unusual one. It was built as a coronation church, around the year 1000 (dedicated in 1009), and as I understand it, someone stole coronation rights from someone else by building it. It's unusual in that it has an apse and an altar at each end, and stranger still, the main altar (St. Martin's) is the western one. The other end is dedicated to St. Stephen. The main entrance is in the side, between the two.

At the right here are some of the colorful paintings (frescoes, I think) above the side aisles and below the clerestory windows. They all date from the 19th century.

The oldest parts of the building are the side towers; from the chevet end, you can see styles from the romanesque through gothic to 19th century baroque. At the right is the ornate pulpit.

At the left here is the altar in a side chapel, and at the right, David walking the length of one side of the adjacent cloister.

At the left here is the altar in a side chapel, and at the right, David walking the length of one side of the adjacent cloister.

The altar is at the "wrong" end of the church, because it's copied from St. Peter's in Rome. The altar at St. Peter's had to be over the saint's grave, but the Vatican hill was in the way of extending the nave in that direction, so they turned hte whole things around, putting the altar at the western end, and this church copied that feature.

The coats of arms at the peaks of the vaults are of the families that endowed construction of their respetive vaults.

The cathedral has one of the largest organs in Germany. The keyboard has six manuals, the largest in Europe. Its many thousand pipes are distributed at several different locatinos aound the nave. The trumpet pipes are behind a small reverse bow window and stick out over it. The keyboard is connected to the pipes by 7 miles of electrical wire, and the sound from the most distant takes a full second to reach the organist!

The place has a 150-member children's choir with a 160-year tradition. It now includes a girls' choir, and when combined with the adult choir can muster 350 singers, who are accompanied by the cathedral's own orchestra.

The WWII bombs that fell here were incendiary, not explosive, so they didn't damage the cathedral too badly.

The city is still nominally catholic; the population is about 34% catholic and 23% protestant. It has one of the oldest and most important Jewish communities in Europe, dating from the the 10th century. The city currently has about 1200 Jewish citizens, as well as about 2000 muslims, mostly Turks. It hosts about 40,000 university students.

Walking between venues, I spotted this poster menu outside a place serving "bubble waffles." Instead of being thick and covered with squire indentations on both sides, they're thin and covered with round proturberances on both sides, like two-sided bubble wrap. I'm not sure what their advantage is over regular waffles, except that, as the poster showed, they can be bent conveniently into cones to be eaten out of hand on the sidewalk. They come in flavors from the simple "Naturality" (dusted with powdered sugar) to the very complex Carla (with vanilla ice cream, nutella, Amarena cherries, a chocolate covered cordial cherry, whipped cream, and powdered sugar). My favorite, at least as a name, was the "marshmallow slime," topped with vanilla and strawberry ice creams, assorted marshmallow shapes, Smarties (British M&M's), and whipped cream. That's it near the middle of the upper half, with the big blue marshmallow on it.

Walking between venues, I spotted this poster menu outside a place serving "bubble waffles." Instead of being thick and covered with squire indentations on both sides, they're thin and covered with round proturberances on both sides, like two-sided bubble wrap. I'm not sure what their advantage is over regular waffles, except that, as the poster showed, they can be bent conveniently into cones to be eaten out of hand on the sidewalk. They come in flavors from the simple "Naturality" (dusted with powdered sugar) to the very complex Carla (with vanilla ice cream, nutella, Amarena cherries, a chocolate covered cordial cherry, whipped cream, and powdered sugar). My favorite, at least as a name, was the "marshmallow slime," topped with vanilla and strawberry ice creams, assorted marshmallow shapes, Smarties (British M&M's), and whipped cream. That's it near the middle of the upper half, with the big blue marshmallow on it.

In a shop window were these large round loaves (maybe a foot across) of nougat candy. They had been neatly sliced into wedges, then the wedges were individually wrapped in cellophane and reassembled into loaves. Around them and behind them were various cookies, biscotti, and sweet breads baked in individual parchment paper wrappers.

In another street, we passed these two windows displaying doilies made of bobbin lace—a craft I admire greatly but have never had the nerve to tackle.

In another street, we passed these two windows displaying doilies made of bobbin lace—a craft I admire greatly but have never had the nerve to tackle.

As we walked, the guide pointed out the special Mainz-specific animated "walking" and "standing" men used on the city's traffic-control lights for pedestrians. They are stocky little characters called "Mainzelmannchen" (little Mainz men) who appear in cartoons between commercials on TV. He emphasized that they are used nowhere else in Germany, but he didn't mention what I found out later, that many German cities have their own custom characters as well. I think Berlin started the trend.

He also pointed out an absolutely brilliant feature of the street-name signs. Blue signs indicate streets that run parallel the river and red ones streets that are perpendicular to it. In addition, house numbers all rise in the direction of the river. Very handy for finding your way around the town! A propos of street names, he assured us that Cherrytree Street did in fact have cherry trees in the 13th century.

The narrow pink house at the far end of this little street is 4 m wide but 13 m deep. It's actually half-timbered, at some juncture, when half-timbering was out of style, the owner had the timbers plastered over and adorned with the white plaster garlands you see in the photo.

The narrow pink house at the far end of this little street is 4 m wide but 13 m deep. It's actually half-timbered, at some juncture, when half-timbering was out of style, the owner had the timbers plastered over and adorned with the white plaster garlands you see in the photo.

Also seen only from a distance was the oldest half-timbered house in town (at the right), 15th century. Its window boxes sprout red geraniums in all directions.

The highlight of the tour was our visit to the Gutenberg Museum. Moveable type had been used before, in 11th-century China. The characters were ceramic and were made by hand, and of course thousands of different ones were needed because of the Chinese writing system, which was not alphabetic.

The highlight of the tour was our visit to the Gutenberg Museum. Moveable type had been used before, in 11th-century China. The characters were ceramic and were made by hand, and of course thousands of different ones were needed because of the Chinese writing system, which was not alphabetic.

Gutenberg's was the first successful use of moveable type in the Western world, where it was eminently more practical, because of the relatively limited number of characters needed. Of course Johannes didn't make it easy on himself by generating just 26 letters and some punctuation. Because he wanted to emulate the existing books of the day, which were hand-lettered in cursive, he made several versions of each letter to accommodate all the different ways they could join to neighboring letters. He wound up with 292 different characters, but that was still way more manageable than the Chinese lexicon.

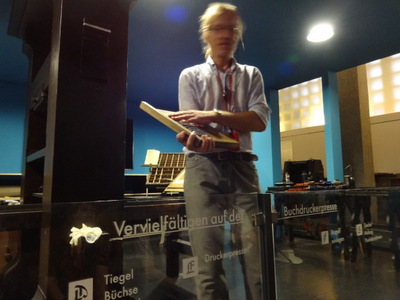

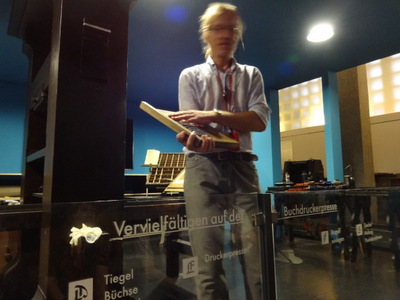

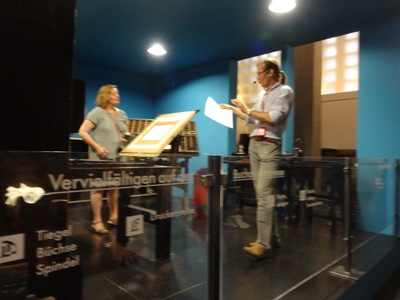

Our guide took us to a room with rows of chairs set up facing a replica of Gutenberg's press. Printing existed in Gutenberg's day—artists could reproduce their work by making woodcuts, hand carved, inking them, and pressing paper over the surface. But for the scale Gutenberg aspired to, hand carving would not (if you'll pardon the expression) cut it. He developed a metal alloy—80% lead, 15% antimony, 5% tin—that had all the right properties: suitable melting point, rapid cooling, sufficient hardness to make the letters durable enough, etc. He made several molds that separated into halves; the two halves could be fastened together to form a tube with, at the bottom, closing the end of the tube, a clay "matrix" with the (negative) impression of the letter in it. Molten alloy poured into the tube was allowed to cool, then the two halves were separated and the matrix removed, leaving a little metal block with the (positive) letter at the end.

Our guide took us to a room with rows of chairs set up facing a replica of Gutenberg's press. Printing existed in Gutenberg's day—artists could reproduce their work by making woodcuts, hand carved, inking them, and pressing paper over the surface. But for the scale Gutenberg aspired to, hand carving would not (if you'll pardon the expression) cut it. He developed a metal alloy—80% lead, 15% antimony, 5% tin—that had all the right properties: suitable melting point, rapid cooling, sufficient hardness to make the letters durable enough, etc. He made several molds that separated into halves; the two halves could be fastened together to form a tube with, at the bottom, closing the end of the tube, a clay "matrix" with the (negative) impression of the letter in it. Molten alloy poured into the tube was allowed to cool, then the two halves were separated and the matrix removed, leaving a little metal block with the (positive) letter at the end.

Further, rather than hand-molding or hand-carving the matrices, he had steel dies made with positive impressions of each letter. To make a matrix, you packed your clay into a little mold of the right size and shape to fit into the casting mold, placed the steel die over it, and thumped it with a hammer, perfectly stamping the right (and precisely reproducible) negative image on the clay. So as matrices wore out, you could make more just like the old ones, and as the moveable characters wore out, you could cast more using the easily made matrices.

Then, of course, he had to develop new ink, because the old water-based ink, fine for woodcuts, wouldn't coat the metal letters properly; it constantly beaded up or slid off. So he came up with an oil-based formula that would do the job.

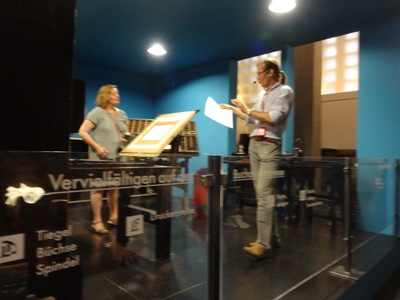

The letters to form a page or section of a page were then assembled in a wooden frame and clamped in place. To apply ink to the letters, he used a sort of leather cushion on a stick that was blotted in the ink, then dabbed all over the text to be printed. Gutenberg made his ink dabbers out of dog leather (the guide is holding one up in one of the photos), because it has no pores and therefore wouldn't soak up the ink, but in his demo, the guide used a modern roller.

The letters to form a page or section of a page were then assembled in a wooden frame and clamped in place. To apply ink to the letters, he used a sort of leather cushion on a stick that was blotted in the ink, then dabbed all over the text to be printed. Gutenberg made his ink dabbers out of dog leather (the guide is holding one up in one of the photos), because it has no pores and therefore wouldn't soak up the ink, but in his demo, the guide used a modern roller.

The guide called for an audience volunteer. He had most of a page from the Gutenberg Bible already set up, but for the inking process, he slide blocks of it apart so that he could roll some of it with black ink and the rest with red. Then he slid the blocks back together and clamped them in place. He and the volunteer loaded a large sheet of paper into a holding frame that folded upward from the bed of the printer, folded the holder down again on top of the inked tupe, slid the whole assembly into the pressing position, and hauled on a wooden windlass to press the paper down onto the inked type. The technology was basically that of a wine press, but Gutenberg added a block to the mechanism that was designed to prevent torque from the windlass from being transmitted to the paper, which would, of course, blur the printed image. Once the volunteer had pushed the big wooden lever as far as she could, the guide (a tall, long-legged, gangly guy) reared back, lifted one foot, and gave the lever a good solid shove with the sole of his boot to ensure good contact. When they unscrewed the mechanism again and slid the paper-holder/inked type assembly back out, the guide was able to peel off and hold up a perfect page of the Bible, with the words of Jesus printed in red.

Obviously, despite what seems like very primitive techniques to us, Gutenberg could produce a handsome Bible a lot cheaper than anybody else. The handwritten ones took ca. three years per copy. But the guide pointed out that he probably didn't sell them any cheaper, because why should he? He produced a superior product—he could perfectly justify the margins, which the hand writers couldn't; the blackness of the letters didn't vary, as it did when the hand-held quills ran out of ink and had to be redipped, etc.—and he had no competition. On the other hand, 30 years later in Paris, printed books sold for half the price of hand-written ones. The two-color text was as fancy as he got, though, so what he sold was a complete set of loose printed pages—Old Testament, New Testament, or both; on paper or on parchment—and the buyer then had them illuminated and bound elsewhere, according to his own taste and budget.

Gutenberg made about 180 copies of the Bible, 30 on parchment the rest on paper; about 48 survive. Note that it took about 80 goats to make enough parchment for one copy.

Although we were allowed to take as many photos as we wanted of the replica press and the demonstration, no photography was allowed in the vault where they keep the real Gutenberg Bibles. The museum owns five copies, some just old or new testament, some complete. Only in 1978 did the museum finally acquire a complete copy, at auction for 3.7 million deutschmarks. They are displayed with some handwritten texts for comparison, some written so small you can hardly read them without a magnifying glass.

Surprisingly little is known about Gutenberg. He was probably a member of the Gensfleisch (yes, "Gooseflesh") family but changed his name; grew up in the goldsmith trade. He was known to be an adult in 1420, died in 1468. He was originally buried in the Franciscan church, but his grave is not there any more. During the last three years of his life, he received an annual a stipend from the archbishop that included 2,180 litres of grain and 2,000 litres of wine, tax-free. When author Umberto Ecco came on this tour, he commented, once he heard how much wine the stipend included, that he now understood why the letters were moving.

The museum also included displays on the various paint and ink-making formulas of the time. Pigment ingredients included lampblack, azurite, white lead, lazuli, indigo, malachite, cochineal, gold, and ochre. Inks were made from, e.g., ferric gallic ink, white aleppo, iron vitriol, saltberries lampblack, and sloe branches. A kit that might be carried by an artist included silver pencils, spoons for measuring ingredients, hells, and parchment pouches filled with paint. The calculations for parchment went like this: two parchment sheets could be made per goatskin; that sufficed for the fronts and backs of two facing pages on each side, i.e., eight pages per goat skin. About 50 goatskins produced enough pages, but about 80 were needed per Bible, to allow for mistakes and spoilage. No discussion of how many dogs it took to keep the print-shop supplied with ink dabbers.

Then it was back to the ship for lunch. I wasn't in the mood for broccoli soup, a roast beef sandwich or sautéed turkey medallions, so I got a salad off the buffet, with the menu's featured starter—rolls of smoked salmon with lemon crème fraiche and asparagus—then went to the pasta station for rigatoni alla Romana (i.e., with garlic creamed spinach and prosciutto).

Then it was back to the ship for lunch. I wasn't in the mood for broccoli soup, a roast beef sandwich or sautéed turkey medallions, so I got a salad off the buffet, with the menu's featured starter—rolls of smoked salmon with lemon crème fraiche and asparagus—then went to the pasta station for rigatoni alla Romana (i.e., with garlic creamed spinach and prosciutto).

For dessert, I skipped the black forest ice cream (chocolate with marinated cherries) and had the pear tarte Bourdalou.

It then occurred to me that I hadn't even poked my nose up onto the sundeck, so I took an after-lunch stroll up there. It was much like the upper deck on the Russian ship. At the right here is a section of the herb garden (rosemary, thyme, mint).

At the left here is a longer view, toward the stern from about the middle of the ship, showing more of the herb garden and the two small putting greens. AT the stern are tables and chairs shaded by café umbrellas. Some folks were up there reading or dozing on loung chairs under the big shade structure (behind me as I took this photo), but it was too hot to stay up there for long.

At the left here is a longer view, toward the stern from about the middle of the ship, showing more of the herb garden and the two small putting greens. AT the stern are tables and chairs shaded by café umbrellas. Some folks were up there reading or dozing on loung chairs under the big shade structure (behind me as I took this photo), but it was too hot to stay up there for long.

At the right is a cute little wooden pleasure boat that we passed in the course of the afternoon.

Throughout the cruise, we encountered a good deal of commercial shipping on the rivers, including flatbed container barges carrying loads of up to 60 or 70 containers each. Here are two shots of "normal" barges, for bulk carriage of commodities in their holds. The one at the left is full; note its very low profile in the water.

Throughout the cruise, we encountered a good deal of commercial shipping on the rivers, including flatbed container barges carrying loads of up to 60 or 70 containers each. Here are two shots of "normal" barges, for bulk carriage of commodities in their holds. The one at the left is full; note its very low profile in the water.

The one at the right is empty or nearly so. See how much higher in the water it rides. When full, it would present as low a profile as the other. They also differ in that the laden one is carrying dry cargo (coal, gravel, grain, or some such); its deck is more or less smooth and only slightly domed. Those blue covers open up so that cargo can be dispensed into the hold from hoppers in port. The empty barge is a tanker, as shown by the maze of pipes that covers its deck. It would carry liquid cargo.

After my stroll around the sundeck, I settled in the lounge for scenic cruising and to work on this diary. A couple of sofas away was a guy who stretched out with his afternoon's entertainment: a fat book, a bottle of water, a bag filled with white-chocolate-covered pretzels, and a sack of red licorice Twizzlers. Definitely a guy who knew what he liked.

I worked away at transcribing my notes and triaging my photos until 4:30 p.m., when the next scheduled activity took place, right there in the lounge: an on onboard talk by Matthias Gemählich, who did his Ph.D. in France and now teaches history at the local university. The talk was fascinating and informative, and being right there in front of my computer, I was able to take much fuller notes than usual.

His title was "Germany and France, A Difficult Partnership."

His first slide presented cartoon characters embodying the stereotypical German and Frenchman. The German wore lederhosen and held a beer stein; he was probably an engineer. The Frenchman held a glass of wine and a baguette and had a cigarette in his mouth; didn't work too hard, enjoyed his country's climate and cuisine.

France has a population of 67 million and is 6th in GDP; Germany has 83 million and is 4th GDP; France is larger in area.

Most of the common border, 450 km, is formed by the Rhine.

German couples average 1.6 children, French ones 2.0.

Manufacturing jobs make of 24.5% in Germany, 15.6% in France.

Strike days per 1000 workers: Germany 17, France 162.

Working hours per week: Germany 38.5, France 35.0.

GDP per capita: Germany 32,400 euros, France 27,900.

AVerage time per day spent for meals: Germany, 1 hr 45 min; France, 2 hr 45 min

German couples who share a bed sleep with separate pillows and separate blanket; the French use traversins (bolsters that span the whole wide of the bed) and share a blanket.

A particularly telling slide showed the French and German railway maps side by side. The one in France is all radial; all roads lead to Paris. Even to travel from Nice to Bordeaux, you have to go through Paris. Germany's is an evenly spread network. Franch has much high-speed rail; Germany too many locals; too many stops.

All administrative and government decisions in France come from Paris. Germany has 16 states, and as in the US, the states have charge of education, and the capital of, e.g, foreign policy. All the various governmental offices in France are in Paris. In Germany, they're headquartered all over the country.

In the Middle Ages, about 800 AD, Charlemagne became "father" of both countries. The Francs were a germanic tribe that invaded. His offspring split his empire into what became France and what became Germany. In france the king managed to become the overall ruler and established a heritary monarchy. The German area became an elective monarchy, the Holy Roman Empire. The king had to curry favor with the electors and therefore gave away parts of his overall power. France became a monolith; Germany was a loose confederation of territories.

Written 19 August 2019

German-French enmity began with Napoleon, who conquered most of Europe, including the German states, which were occupied at the beginning of the 19th century. That led to the first sense of German nationalism, in opposition to the common enemy—France. William I (and Otto von Bismarck) used that impetus to unite Germany in 1871. The unification ceremony took place at Versailles after France was defeated (in the Franco-Prussian war); France had to pay reparations and lost Alsace and Lorraine. The Niederwald Monument and that huge statue of William I in Koblenz commemorate that event.

Then France's side won WWI—the greatest fatalities on both sides of that war were along the French-German border. The worst battle was Verdun; nobody won that one. France got Alsace and Lorraine back, and Germany had to pay reparations.

Hitler swore to tear up that treaty, and he did. When he conquered France, he inflicted a series of humiliations, including signing of armistice in the very same rail car where the WWI treaty was signed. The German occupation of France was very harsh; about half of French Jews were deported. Then, a couple of month later, in June of 1944, the Normandy invasion took place. When Germany surrendered, it was partitioned among France, the U.S., Britain, and Russia.

In the early 1960's, Charles De Gaulle (France) and Konrad Adenauer (first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany) set out to effect real reconciliation. They signed the 1963 Elysee treaty stating that the French and German goverments would meet at least twice a year to arrive at a common understanding on what to do about world events and to make concrete plans for exchange programs and common restoration projects. Fortunately, their successors accepted the treaty and continued the trend. At Douaumont in 1984, Mitterand and Helmut Kohl came together together for a service commemorating victoims of Verdun.

Another critical juncture was 1989, with German reunification. Some French worried about Germany getting bigger, but the change didn't seem to do any permanent damage to the relationship.

Commonalities now include ARTE (German and French public TV, you pick the language to watch in); and a history book that is available for use in both countries, in both French and German.

The two countries are now something like the driving force behind the European Union, although each country has a party that dislikes it. The Front National held a rally in Paris in 2014; it's a France-first party that advocates "Frexit" and leaving the euro currency. The Alternative for Germany, (Berlin 2015) is a Germany-first party that hate refugee immigration.

Macron, young liberal internationalist, wants to reform the French job market, and the Yellow Vests hate that. Macron has made some concessions to defuse them (he calls it the great national debate, and he travels around explaining it). Angela Merkel, an experienced policitian, chancellor of Germany since 2005, is conservative, but people say she's not conservative enough any more; she gets criticized by her own party. The two have their differences about the EU. He wants a common budget for all the European countries, and taht's not popular in Germany; Germans think they'll wind up subsidizing everybody else.

Immigration policy differences have been sorted out, but military policies differ; France often intervenes in foreign conflicts; Germany doesn't.

Nuclear power is another point of difference. Germany is getting rid of its nuclear plants, with a target date of 2022; they only have 7 left. France has about 58 and plans to keep them.

The EU has 28 countries now (27 after Brexit). Europe has gone 74 years now without major military conflict—the longest time in its history!

Audience question: How long were Germaby ad France united under Charlemagne and his descendents? Answer: Maybe 200 years.

Audience question: Why won't Germany pay for NATO? Answer: Germany hesitates to militarize since the world wars.

After the lecture, when Devin showed up to conduct our briefing about the following day, he had donned his lederhosen! This was the night we were treated to the special "taste of Germany" dinner, and the staff had dressed the part. Devin explained that the color and cut of his outfit revealed that he was from the country. In contrast, the waiter on the right in the right-hand photo is from the city. His shorts, although still short, are longer than Devin's. His companion models the classic German "dirndl" dress.

After the lecture, when Devin showed up to conduct our briefing about the following day, he had donned his lederhosen! This was the night we were treated to the special "taste of Germany" dinner, and the staff had dressed the part. Devin explained that the color and cut of his outfit revealed that he was from the country. In contrast, the waiter on the right in the right-hand photo is from the city. His shorts, although still short, are longer than Devin's. His companion models the classic German "dirndl" dress.

During the briefing, we cast off and headed for Speyer.

The German menu began with two appetizer boards for everyone at the table to share. The one at the left presents a variety of sausages and cold cuts. If included, among other things, more of that treat blutwurst, but this time cold and unfried. The two little dishes contain pickled vegetables and seasoned pork fat (for spreading like butter).

The German menu began with two appetizer boards for everyone at the table to share. The one at the left presents a variety of sausages and cold cuts. If included, among other things, more of that treat blutwurst, but this time cold and unfried. The two little dishes contain pickled vegetables and seasoned pork fat (for spreading like butter).

The board at the right is loaded with cheeses and dried fruit. The nearer of the two little bowls is Liptauer cheese, and I never got to taste the other.

In the center of each table was a rack loaded with soft pretzels and draped with a couple of long dry sausages. I'm told the pretzels were pretty good; no one tried the sausage. The wooden bowl of interestingly shaped breads in the lower left corner looked promising but proved disappointing. They were all as hard and dry as hard pretzels. You could break your teeth trying to eat them.

In the center of each table was a rack loaded with soft pretzels and draped with a couple of long dry sausages. I'm told the pretzels were pretty good; no one tried the sausage. The wooden bowl of interestingly shaped breads in the lower left corner looked promising but proved disappointing. They were all as hard and dry as hard pretzels. You could break your teeth trying to eat them.

At the foot of the pretzel rack was the list of items we each got on our main plate: "backhendle pumpkin-seed crusted chicken thigh with potato salad; sauerbraten (braised beef); bread dumpling; red cabbage; grilled kasekrainer (cheese sausage); sauerkraut.

But first, we were served "wedding soup": beef broth with diced beef, carrots and zucchini.

But first, we were served "wedding soup": beef broth with diced beef, carrots and zucchini.

At the right is the ready-assembled plate of food brought to each of us. Clockwise from the white spherical bread dumpling at the top: parsley sprig and below it the sauerkraut; the chunk of cheese sausage; large slices of tasty and tender sauerbraten, hiding most of the braised red cabbage, which was underneath it; some of the German potato salad; and the backhendl, hiding more of the potato salad. I was underwhelmed. The sauerkrauten was pretty good, and the backhandl very good, but the potato salad was way too sour, and the red cabbage and sauerkraut were both so overcooked there wasn't much left to their flavor. I didn't care for the sausage, and the dumpling was hopelessly gummy and bland.

So I ate a good deal of the backhendl and some of the sauerbraten and sauerkraut, then pushed the plate aside and went to see what was on the buffet of other German dishes they had set up in case we were still hungry.

So I ate a good deal of the backhendl and some of the sauerbraten and sauerkraut, then pushed the plate aside and went to see what was on the buffet of other German dishes they had set up in case we were still hungry.

At the left here is my second plate. Clockwise from 1 o'clock: spätzle (little boiled dumplings) with cream, cheese, and crispy onions (not such a much, to my surprise, since I like spätzle and all the stuff they put on it); very good cucumber salad (the cucumber was salted down to wilt it, then dressed with vinegar, salt, and pepper); a small piece of a bratwurst (icky; I usually like bratwurst, but this one was badly overemulsified, smoother inside than a hot dog; definitely not to my taste); and TA-DA! the winner of the whole dinner! Roasted pork knuckles. Wow, was that good.

At the right here is now it looked in its baking dish. The skin was tender and crackling crisp, and underneath, the pork was meltingly tender and deeply flavorful. The next day, I passed the chef in the hallway and stopped to compliment him on the dish. He said they boil it slowly for six hours, then put it in a very hot oven and roast the heck out of it. [So now, back in Tallahassee, I'm experimenting with that technique. The limiting factor is finding cuts of fresh pork that still have the skin on. I started with a couple of pig's feet, and it worked great—excellent crispy skin but hardly any meat to speak of. Then I found some pork hocks, and they were even better, but still too many bones to suit David. Also it's hard to find whole hocks, they're usually split. Right now, in my fridge, I've got a whole pork shoulder, with the skin (courtesy of Winn Dixie; Publix always peels the skin off everything) that I'm trying for an upcoming Sunday dinner. It won't be the same, of course, with bland American pork, but it could be darn good!]

Here, at the left, is the sausage-and-sauerkraut station on the buffet. The long pale sausages are the bratwurst; the others are the same as those on the main plates.

Here, at the left, is the sausage-and-sauerkraut station on the buffet. The long pale sausages are the bratwurst; the others are the same as those on the main plates.

At this point, someone at the table mentioned to the waiter that it was her companion's birthday, and minutes later, this lovely passion-fruit Bavarian cream cake emerged from the kitchen, on a plate decorated with piped chocolate and sporting a blazing candle! They must keep a variety of them in the cooler all the time for special occasions. The waiter cut it up and distributed it to all of us at the table.

Also on the buffet was a variety of desserts, some of which I remembered from the German afternoon tea, like the Linzertort and the apple crumble shown here at the left.

Also on the buffet was a variety of desserts, some of which I remembered from the German afternoon tea, like the Linzertort and the apple crumble shown here at the left.

They also offered several kinds of cake, like these little caramel-and-chocolate squares.

Also platters of fruit (alas, the figs were too underripe to be enjoyable, but the watermelon was great), and chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry ice creams with nuts, sauces, and sprinkles.

Also platters of fruit (alas, the figs were too underripe to be enjoyable, but the watermelon was great), and chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry ice creams with nuts, sauces, and sprinkles.

And more cakes.

Finally, a large chafing dish was filled with these little spindle-shaped dumplings called "brezenknödel," which were simmering in a sweet syrup. I tried one, but they were hard and chewy. Not appetizing (at least not after the rest of that dinner!).

Finally, a large chafing dish was filled with these little spindle-shaped dumplings called "brezenknödel," which were simmering in a sweet syrup. I tried one, but they were hard and chewy. Not appetizing (at least not after the rest of that dinner!).

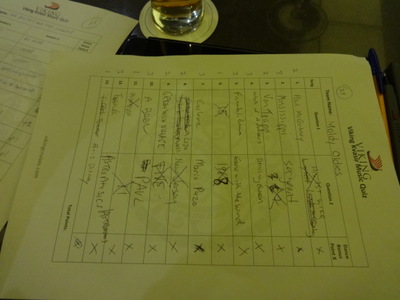

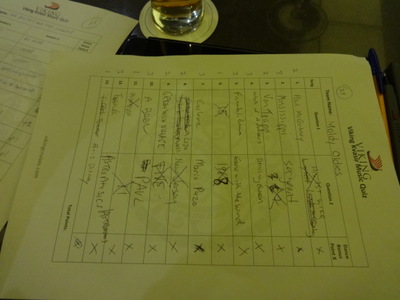

After dinner, David went back to his stateroom, but I stayed on for the evening's quiz game, joining the same team again. This time it was popular-culture questions: "What does the name of the band ABBA signify, and what was their first big hit?" "Who wrote the

book the movie The Wizard of Oz was based on, and what movie won the Oscar the year that The Wizard of Oz was nominated?" "In what state was Elvis born, and what rank did he reach in the army?" Etc. You can see all the crosses where we got questions wrong. We still came in second, though.

Previous entry

List of Entries

Next entry

The Kvasir docked in Mainz during the on-board concert on Thursday evening, and the evening's briefing presented cruel choices. Friday morning, we could go on the included city walking tour, which included the cathedral and the Gutenberg museum and demonstration of Gutenberg printing technology. Or we could join the simultaneous optional walking tour of historic Mainz and St. Stephens's church to see yet more Chagall windows. Or we could go off on our own to see the Museum of Ancient Seafaring, which displayed nine 4th-century Roman ships made of German oak that were found buried in clay during construction of a riverside hotel. Drat. In the end, we went for the Gutenberg—I had always wanted to see that. But I was really sorry to miss the Roman ships.

The Kvasir docked in Mainz during the on-board concert on Thursday evening, and the evening's briefing presented cruel choices. Friday morning, we could go on the included city walking tour, which included the cathedral and the Gutenberg museum and demonstration of Gutenberg printing technology. Or we could join the simultaneous optional walking tour of historic Mainz and St. Stephens's church to see yet more Chagall windows. Or we could go off on our own to see the Museum of Ancient Seafaring, which displayed nine 4th-century Roman ships made of German oak that were found buried in clay during construction of a riverside hotel. Drat. In the end, we went for the Gutenberg—I had always wanted to see that. But I was really sorry to miss the Roman ships.

Our stroll from the ship into the town led us through yet another beautiful allée of sycamores.

Our stroll from the ship into the town led us through yet another beautiful allée of sycamores.

In Fischtor Square, we passed a pair of these graceful fountains feature large leaping fish. Of course, I asked the guide what kind they were, and of course he said nobody was sure, but some people think they look like salmon, which occurred historically in the river. Salmon? Really? With that long, pointed, bony snout? I think they were pike. I wish I'd gotten a closer photo, but you can Google up a much better image by searching on "Public Fish Fountain on Fischtor Square."

In Fischtor Square, we passed a pair of these graceful fountains feature large leaping fish. Of course, I asked the guide what kind they were, and of course he said nobody was sure, but some people think they look like salmon, which occurred historically in the river. Salmon? Really? With that long, pointed, bony snout? I think they were pike. I wish I'd gotten a closer photo, but you can Google up a much better image by searching on "Public Fish Fountain on Fischtor Square."

To my delight, a market was in progress in one of the squares we passed throughmdash;it's apparently there every Tuesday, Friday, and Saturday.At the left is a stand selling flavored oils. It's particularly pushing cumin oil, for health.

To my delight, a market was in progress in one of the squares we passed throughmdash;it's apparently there every Tuesday, Friday, and Saturday.At the left is a stand selling flavored oils. It's particularly pushing cumin oil, for health.

At the left here a pork butcher is selling cooked and raw meat and sausages. The meat is under glass, and the green stuff is just reflections of the foliage of a nearby tree.

At the left here a pork butcher is selling cooked and raw meat and sausages. The meat is under glass, and the green stuff is just reflections of the foliage of a nearby tree.

The vegetables were beautiful. Note the lovely purple cauliflower at the lower left, beside big bundles of fresh mint. Above them are fennel bulbs, speckled and baby fava beans in the shell, English peas, and a big bunch of fresh dill.

The vegetables were beautiful. Note the lovely purple cauliflower at the lower left, beside big bundles of fresh mint. Above them are fennel bulbs, speckled and baby fava beans in the shell, English peas, and a big bunch of fresh dill.

At the left here are "sweet 100" tomatoes on the vine, "heirloom" tomatoes of funny shapes and colors, ginger root, red and white onions, fat eggplants, and in the center "king eryngii" mushrooms, mostly thick meaty stem.

At the left here are "sweet 100" tomatoes on the vine, "heirloom" tomatoes of funny shapes and colors, ginger root, red and white onions, fat eggplants, and in the center "king eryngii" mushrooms, mostly thick meaty stem.

At the left here is a big bin of chanterelles. The adjacent stall had an even larger crate of them, but they looked less fresh and somewhat dried out. I didn't get a shot showing the prices, so I don't know whether they cost the same.

At the left here is a big bin of chanterelles. The adjacent stall had an even larger crate of them, but they looked less fresh and somewhat dried out. I didn't get a shot showing the prices, so I don't know whether they cost the same.

This three-columned well was a 16th-century gift from the ruler (prince-elector and cardinal Albert) to his people, whom he had just subdued, to remind them who was boss. I couldn't get all of it into the photo, but it's topped by a tall ornate spire that culminates in a seated bishop with a smaller figure wearing a crown over his head. I'd bet those are Albert and above him God.

This three-columned well was a 16th-century gift from the ruler (prince-elector and cardinal Albert) to his people, whom he had just subdued, to remind them who was boss. I couldn't get all of it into the photo, but it's topped by a tall ornate spire that culminates in a seated bishop with a smaller figure wearing a crown over his head. I'd bet those are Albert and above him God.

The cathedral is an unusual one. It was built as a coronation church, around the year 1000 (dedicated in 1009), and as I understand it, someone stole coronation rights from someone else by building it. It's unusual in that it has an apse and an altar at each end, and stranger still, the main altar (St. Martin's) is the western one. The other end is dedicated to St. Stephen. The main entrance is in the side, between the two.

The cathedral is an unusual one. It was built as a coronation church, around the year 1000 (dedicated in 1009), and as I understand it, someone stole coronation rights from someone else by building it. It's unusual in that it has an apse and an altar at each end, and stranger still, the main altar (St. Martin's) is the western one. The other end is dedicated to St. Stephen. The main entrance is in the side, between the two.

At the left here is the altar in a side chapel, and at the right, David walking the length of one side of the adjacent cloister.

At the left here is the altar in a side chapel, and at the right, David walking the length of one side of the adjacent cloister.

Walking between venues, I spotted this poster menu outside a place serving "bubble waffles." Instead of being thick and covered with squire indentations on both sides, they're thin and covered with round proturberances on both sides, like two-sided bubble wrap. I'm not sure what their advantage is over regular waffles, except that, as the poster showed, they can be bent conveniently into cones to be eaten out of hand on the sidewalk. They come in flavors from the simple "Naturality" (dusted with powdered sugar) to the very complex Carla (with vanilla ice cream, nutella, Amarena cherries, a chocolate covered cordial cherry, whipped cream, and powdered sugar). My favorite, at least as a name, was the "marshmallow slime," topped with vanilla and strawberry ice creams, assorted marshmallow shapes, Smarties (British M&M's), and whipped cream. That's it near the middle of the upper half, with the big blue marshmallow on it.

Walking between venues, I spotted this poster menu outside a place serving "bubble waffles." Instead of being thick and covered with squire indentations on both sides, they're thin and covered with round proturberances on both sides, like two-sided bubble wrap. I'm not sure what their advantage is over regular waffles, except that, as the poster showed, they can be bent conveniently into cones to be eaten out of hand on the sidewalk. They come in flavors from the simple "Naturality" (dusted with powdered sugar) to the very complex Carla (with vanilla ice cream, nutella, Amarena cherries, a chocolate covered cordial cherry, whipped cream, and powdered sugar). My favorite, at least as a name, was the "marshmallow slime," topped with vanilla and strawberry ice creams, assorted marshmallow shapes, Smarties (British M&M's), and whipped cream. That's it near the middle of the upper half, with the big blue marshmallow on it.

In another street, we passed these two windows displaying doilies made of bobbin lace—a craft I admire greatly but have never had the nerve to tackle.

In another street, we passed these two windows displaying doilies made of bobbin lace—a craft I admire greatly but have never had the nerve to tackle.

The narrow pink house at the far end of this little street is 4 m wide but 13 m deep. It's actually half-timbered, at some juncture, when half-timbering was out of style, the owner had the timbers plastered over and adorned with the white plaster garlands you see in the photo.

The narrow pink house at the far end of this little street is 4 m wide but 13 m deep. It's actually half-timbered, at some juncture, when half-timbering was out of style, the owner had the timbers plastered over and adorned with the white plaster garlands you see in the photo.

The highlight of the tour was our visit to the Gutenberg Museum. Moveable type had been used before, in 11th-century China. The characters were ceramic and were made by hand, and of course thousands of different ones were needed because of the Chinese writing system, which was not alphabetic.

The highlight of the tour was our visit to the Gutenberg Museum. Moveable type had been used before, in 11th-century China. The characters were ceramic and were made by hand, and of course thousands of different ones were needed because of the Chinese writing system, which was not alphabetic.

Our guide took us to a room with rows of chairs set up facing a replica of Gutenberg's press. Printing existed in Gutenberg's day—artists could reproduce their work by making woodcuts, hand carved, inking them, and pressing paper over the surface. But for the scale Gutenberg aspired to, hand carving would not (if you'll pardon the expression) cut it. He developed a metal alloy—80% lead, 15% antimony, 5% tin—that had all the right properties: suitable melting point, rapid cooling, sufficient hardness to make the letters durable enough, etc. He made several molds that separated into halves; the two halves could be fastened together to form a tube with, at the bottom, closing the end of the tube, a clay "matrix" with the (negative) impression of the letter in it. Molten alloy poured into the tube was allowed to cool, then the two halves were separated and the matrix removed, leaving a little metal block with the (positive) letter at the end.

Our guide took us to a room with rows of chairs set up facing a replica of Gutenberg's press. Printing existed in Gutenberg's day—artists could reproduce their work by making woodcuts, hand carved, inking them, and pressing paper over the surface. But for the scale Gutenberg aspired to, hand carving would not (if you'll pardon the expression) cut it. He developed a metal alloy—80% lead, 15% antimony, 5% tin—that had all the right properties: suitable melting point, rapid cooling, sufficient hardness to make the letters durable enough, etc. He made several molds that separated into halves; the two halves could be fastened together to form a tube with, at the bottom, closing the end of the tube, a clay "matrix" with the (negative) impression of the letter in it. Molten alloy poured into the tube was allowed to cool, then the two halves were separated and the matrix removed, leaving a little metal block with the (positive) letter at the end.

The letters to form a page or section of a page were then assembled in a wooden frame and clamped in place. To apply ink to the letters, he used a sort of leather cushion on a stick that was blotted in the ink, then dabbed all over the text to be printed. Gutenberg made his ink dabbers out of dog leather (the guide is holding one up in one of the photos), because it has no pores and therefore wouldn't soak up the ink, but in his demo, the guide used a modern roller.

The letters to form a page or section of a page were then assembled in a wooden frame and clamped in place. To apply ink to the letters, he used a sort of leather cushion on a stick that was blotted in the ink, then dabbed all over the text to be printed. Gutenberg made his ink dabbers out of dog leather (the guide is holding one up in one of the photos), because it has no pores and therefore wouldn't soak up the ink, but in his demo, the guide used a modern roller.

Then it was back to the ship for lunch. I wasn't in the mood for broccoli soup, a roast beef sandwich or sautéed turkey medallions, so I got a salad off the buffet, with the menu's featured starter—rolls of smoked salmon with lemon crème fraiche and asparagus—then went to the pasta station for rigatoni alla Romana (i.e., with garlic creamed spinach and prosciutto).

Then it was back to the ship for lunch. I wasn't in the mood for broccoli soup, a roast beef sandwich or sautéed turkey medallions, so I got a salad off the buffet, with the menu's featured starter—rolls of smoked salmon with lemon crème fraiche and asparagus—then went to the pasta station for rigatoni alla Romana (i.e., with garlic creamed spinach and prosciutto).

At the left here is a longer view, toward the stern from about the middle of the ship, showing more of the herb garden and the two small putting greens. AT the stern are tables and chairs shaded by café umbrellas. Some folks were up there reading or dozing on loung chairs under the big shade structure (behind me as I took this photo), but it was too hot to stay up there for long.

At the left here is a longer view, toward the stern from about the middle of the ship, showing more of the herb garden and the two small putting greens. AT the stern are tables and chairs shaded by café umbrellas. Some folks were up there reading or dozing on loung chairs under the big shade structure (behind me as I took this photo), but it was too hot to stay up there for long.

Throughout the cruise, we encountered a good deal of commercial shipping on the rivers, including flatbed container barges carrying loads of up to 60 or 70 containers each. Here are two shots of "normal" barges, for bulk carriage of commodities in their holds. The one at the left is full; note its very low profile in the water.

Throughout the cruise, we encountered a good deal of commercial shipping on the rivers, including flatbed container barges carrying loads of up to 60 or 70 containers each. Here are two shots of "normal" barges, for bulk carriage of commodities in their holds. The one at the left is full; note its very low profile in the water.

After the lecture, when Devin showed up to conduct our briefing about the following day, he had donned his lederhosen! This was the night we were treated to the special "taste of Germany" dinner, and the staff had dressed the part. Devin explained that the color and cut of his outfit revealed that he was from the country. In contrast, the waiter on the right in the right-hand photo is from the city. His shorts, although still short, are longer than Devin's. His companion models the classic German "dirndl" dress.

After the lecture, when Devin showed up to conduct our briefing about the following day, he had donned his lederhosen! This was the night we were treated to the special "taste of Germany" dinner, and the staff had dressed the part. Devin explained that the color and cut of his outfit revealed that he was from the country. In contrast, the waiter on the right in the right-hand photo is from the city. His shorts, although still short, are longer than Devin's. His companion models the classic German "dirndl" dress.

The German menu began with two appetizer boards for everyone at the table to share. The one at the left presents a variety of sausages and cold cuts. If included, among other things, more of that treat blutwurst, but this time cold and unfried. The two little dishes contain pickled vegetables and seasoned pork fat (for spreading like butter).

The German menu began with two appetizer boards for everyone at the table to share. The one at the left presents a variety of sausages and cold cuts. If included, among other things, more of that treat blutwurst, but this time cold and unfried. The two little dishes contain pickled vegetables and seasoned pork fat (for spreading like butter).

In the center of each table was a rack loaded with soft pretzels and draped with a couple of long dry sausages. I'm told the pretzels were pretty good; no one tried the sausage. The wooden bowl of interestingly shaped breads in the lower left corner looked promising but proved disappointing. They were all as hard and dry as hard pretzels. You could break your teeth trying to eat them.

In the center of each table was a rack loaded with soft pretzels and draped with a couple of long dry sausages. I'm told the pretzels were pretty good; no one tried the sausage. The wooden bowl of interestingly shaped breads in the lower left corner looked promising but proved disappointing. They were all as hard and dry as hard pretzels. You could break your teeth trying to eat them.

But first, we were served "wedding soup": beef broth with diced beef, carrots and zucchini.

But first, we were served "wedding soup": beef broth with diced beef, carrots and zucchini.

So I ate a good deal of the backhendl and some of the sauerbraten and sauerkraut, then pushed the plate aside and went to see what was on the buffet of other German dishes they had set up in case we were still hungry.

So I ate a good deal of the backhendl and some of the sauerbraten and sauerkraut, then pushed the plate aside and went to see what was on the buffet of other German dishes they had set up in case we were still hungry.

Here, at the left, is the sausage-and-sauerkraut station on the buffet. The long pale sausages are the bratwurst; the others are the same as those on the main plates.

Here, at the left, is the sausage-and-sauerkraut station on the buffet. The long pale sausages are the bratwurst; the others are the same as those on the main plates.

Also on the buffet was a variety of desserts, some of which I remembered from the German afternoon tea, like the Linzertort and the apple crumble shown here at the left.

Also on the buffet was a variety of desserts, some of which I remembered from the German afternoon tea, like the Linzertort and the apple crumble shown here at the left.

Also platters of fruit (alas, the figs were too underripe to be enjoyable, but the watermelon was great), and chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry ice creams with nuts, sauces, and sprinkles.

Also platters of fruit (alas, the figs were too underripe to be enjoyable, but the watermelon was great), and chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry ice creams with nuts, sauces, and sprinkles.

Finally, a large chafing dish was filled with these little spindle-shaped dumplings called "brezenknödel," which were simmering in a sweet syrup. I tried one, but they were hard and chewy. Not appetizing (at least not after the rest of that dinner!).

Finally, a large chafing dish was filled with these little spindle-shaped dumplings called "brezenknödel," which were simmering in a sweet syrup. I tried one, but they were hard and chewy. Not appetizing (at least not after the rest of that dinner!).