About 6 a.m., the Kvasir tied up in Speyer, home (as the Viking Daily tells us) of the largest of the three Romanesque imperial cathedrals.

About 6 a.m., the Kvasir tied up in Speyer, home (as the Viking Daily tells us) of the largest of the three Romanesque imperial cathedrals.Saturday, 29 June, Speyer, with "wild" life

Written 20 August 2019

About 6 a.m., the Kvasir tied up in Speyer, home (as the Viking Daily tells us) of the largest of the three Romanesque imperial cathedrals.

About 6 a.m., the Kvasir tied up in Speyer, home (as the Viking Daily tells us) of the largest of the three Romanesque imperial cathedrals.

I'd been admiring the poached eggs ordered at breakfast by some of my fellow passengers, so this morning, I ordered one. I got two, but only ate one (which was perfect). When the waiter asked if something was wrong with the other one, I reminded him I had ordered just one poached egg. Sorry, he said, the standard order is two and he couldn't talk the kitchen out of it.

At the right here is a better view of the network of piping and pumps that marks the deck of a tanker. This one must be about half full, judging by its freeboard.

Some passengers set off by bus at 8:30 a.m. to tour Heidelberg and Martin Luther's Worms, but we had opted for the 9:00 a.m. walking tour of the town and the cathedral. Again we were sorry to miss other choices, like the museum of transportation tech (which includes full-size rockets and jetliners) and the temporary exhibition of German toys in another local museum.

As our guide led us from the river through a series of gardens toward the town, we passed these two statues. At the left is a ferryman being hailed. At the right a group representing some of the kings buried in the cathedral.

As our guide led us from the river through a series of gardens toward the town, we passed these two statues. At the left is a ferryman being hailed. At the right a group representing some of the kings buried in the cathedral.

The guide used the time to fill us in on a little history. Speyer was founded (as "Marcus new field") between 8 and 12 BC as a Roman miliary camp, on the site where the cathedral now stands. It had become quite a large garrison by the middle of the 1st century AD. The Rhine was the eastern border of the Roman empire. (Currently, on the left bank is Rhineland Palatinate, on the other is Baden-Württemberg.)

The Romans were here until the middle of the 3rd century AD. Two centuries later, in 476, the western part of the Roman empire ended. (The eastern part ended in the 16th century; its capital was Constantinople.) For 200 years, nobody lived here.

The most important Germanic tribe, the Franconians, came from the east in the middle of the 5th century. In 800, Charlemagne (a Franconian), was made first emperor of the holy roman empire. He was followed by the Merovingiens and Carolingiens. Some of the FRanconians moved west, joined these, and founded Burgundy and the kingdom of France. The first Franconian name for the place was "Spira" (from the Italian), and that became "Speyer." For 100 more years, nothing much happened.

In 1024, Conrad of this area was elected king of the Holy Roman Empire. He was the one who set out to build the giant cathedral and crypt for his family to be buried in; up to then, they'd been buried in Worms. Three years later, in 1027, the pope crowned him emperor. That empire continued to 1918.

Here at the left, glimpsed through the trees in the park, is one of the five remaining "heathen towers," remnants of 70 towers of the 13th-century medieval fortifications. The rest were destroyed in 1689, by Louis XIV, who, as usual, came through and destroyed the town) on his retreat after an occupation of two years.

Here at the left, glimpsed through the trees in the park, is one of the five remaining "heathen towers," remnants of 70 towers of the 13th-century medieval fortifications. The rest were destroyed in 1689, by Louis XIV, who, as usual, came through and destroyed the town) on his retreat after an occupation of two years.

As we stood looking at it, a few mosquitos showed up, so we moved on. The guide explained that the local mosquito-control authorities are dead in the water, because both of their helicopters are out of commission, so the mosquitos are bad. But the guide assured us that the mosquito season is only about two weeks, so they'll be gone by the time of the bretzel festival, which is coming up shortly. Now there's a concept—a mosquito season that ends spontaneously while the weather remains good. Short of a blizzard, our mosquito season never ends!

Once we turned the end of the line of trees, more of the section of surviving wall was visible, shown here at the right.

After a few more steps, we got our first sight of the cathedral, viewed from the chevet end. The column at the right lists the founders (i.e., the kings who had it built) and the first few bishops.

After a few more steps, we got our first sight of the cathedral, viewed from the chevet end. The column at the right lists the founders (i.e., the kings who had it built) and the first few bishops.

As the guide was explaining the building's origins, a good-sized green bird flew by. As it passed overhead, it presented a nice silhouette of its head and beak, confirming my suspicions. My jaw dropped, and I exclaimed, "That was a parrot!" "Oh, yes," the guide replied, without missing a beat, "several of them escaped from our zoo some years ago, and they've stayed and multiplied. We have a whole colony now, between 80 and 100." The cathedral also has a family of hawks in the tower to defend the cathedral against doves (the guide said doves, but I think he meant pigeons, which are, after all, rock doves).

The cathedral was begun (with the east end and high vault) in 1030 under Konrad II. It was finished and consecrated in October of 1061, under his grandson Henry IV, although at the time it didn't have towers or a gallery. At 134 m long, it was the largest Romanesque church in the world. Then around 1090, Henry IV had it torn down to the level of the walls and renovated.

Here are a couple of views of the facade, which is neo-romanesque, from the 1850's, same priod as the paintings inside. I wasn't able to get a good photo of the whole building, but if you just Google "Speyer cathedral," you can see some magnificent aerial shots.

Here are a couple of views of the facade, which is neo-romanesque, from the 1850's, same priod as the paintings inside. I wasn't able to get a good photo of the whole building, but if you just Google "Speyer cathedral," you can see some magnificent aerial shots.

The vestry has gothic (pointed) arches, because it was built later, and when fashions changed, the construction tended to change with them, even when it meant that parts of the building didn't "match."

The dome, built in the 19th century is gothic and baroque.

It would take considerable time and study to work out all the changes in construction and architectural style visible in the building. It's considered an architectural landmark and has influenced architecture all over Europe, but it also been damaged, patched, renovated, nearly destroyed, rebuilt, etc.

It would take considerable time and study to work out all the changes in construction and architectural style visible in the building. It's considered an architectural landmark and has influenced architecture all over Europe, but it also been damaged, patched, renovated, nearly destroyed, rebuilt, etc.

When the original section went up, the builders did not have cranes. The only way to get stones up to the tops of the walls was to push them up ramps. Then, by the time of Henry IV's renovation, cranes were invented, so he was able to build higher and to add towers. The guide pointed out the difference in appearance of the bricks and stones at the level of the renovation.

In addition, when Louis XIV came through in the 17th century, it was burned. Louis didn't mean to burn the cathedral, but when he torched the town, the flames spread, and the cathedral roof collapsed, together with a section of one side wall. In the photo at the right, you can see the change in the stones marking that repair.

The guide also explained that the building has a hypocaust, dating from its original construction, but it has never worked very effectively, so the church was always cold inside. Modern renovations have added more effective heating, as well as fire doors and piping for use by fire fighters.

The photo at the right shows the door we entered through, in the side wall of the building. The doors are bronze, enormous, and very heavy. Given a substantial tug, they glide open smoothly and silently, but released they apparently close with a thunderous boom. As a result, the stout leather bag is kept strapped to the handles to keep them slightly ajar and prevent hearing damage.

Inside, that is one long tall nave (33 m high)! Speyer was the largest church in Christendom until Cluny was built, a little later. And of course, Speyer has the merit of still being there, whereas Cluny is in ruins. Again, the panels above the side arches and below the clerestory were painted in the 19th century.

Inside, that is one long tall nave (33 m high)! Speyer was the largest church in Christendom until Cluny was built, a little later. And of course, Speyer has the merit of still being there, whereas Cluny is in ruins. Again, the panels above the side arches and below the clerestory were painted in the 19th century.

Here, at the left, is the view the other way down the nave—taken from the same spot as the one above; that nave is really long. You can see some of the pipes of the organ at the end.

Here, at the left, is the view the other way down the nave—taken from the same spot as the one above; that nave is really long. You can see some of the pipes of the organ at the end.

At the right is a rather distant view of the altar; even the choir was really deep front to back.

As usual, in a cathedral, I went over to see whether the side aisles continued around to meet behind the altar (some do, and some don't, and there's often good art back there if they do), though I didn't get far enough to see. I didn't want to wander too far, in case the guide moved on without me.

And as I walked up the side aisle past the choir, I was arrested by the discovery of this amazing carved wooden object, which the guide never mentioned, and which I never got a chance to ask about. What is it?! A table? It's covered with carved animals and some rather menacing plants. Note the large spiny-backed lizard on the lower right foot and the even larger spiny tail of something disappearing around the table leg.

And as I walked up the side aisle past the choir, I was arrested by the discovery of this amazing carved wooden object, which the guide never mentioned, and which I never got a chance to ask about. What is it?! A table? It's covered with carved animals and some rather menacing plants. Note the large spiny-backed lizard on the lower right foot and the even larger spiny tail of something disappearing around the table leg.

In the right-hand photo is a closer view of the raven at the left edge of the table. Just to the right of the raven is a large frog, and further to the right a rat.

The shape of the whole thing is reminiscent of some sort of shelf fungus. At the left here is a close-up of the creature on one of the lower shelves. A stylized scorpion? A decapod crustacean? A trilobyte?! All I can hypothesize is that it's some sort of funerary monument, intended to remind us of death and decay.

The shape of the whole thing is reminiscent of some sort of shelf fungus. At the left here is a close-up of the creature on one of the lower shelves. A stylized scorpion? A decapod crustacean? A trilobyte?! All I can hypothesize is that it's some sort of funerary monument, intended to remind us of death and decay.

As we left the cathedral, the guide paused to point out some of the water piping retrofitted in the 2000's.

In WWII, the allies chose not to destroy Speyer or Heidelberg, They had no railway junctions, military suipport structures, or significant industry, so the cathedral was spared.

On our walk to the net venue, the protestant church, the guide told us about the upcoming festival, two weeks from now: it's a huge wine tasting and bretzel tasting, annual since 1910.

He also revealed that the residents of Speyer are not great beer drinkers. Instead, they drink weinschorle (wine spritzer), from half-liter mugs. Theoretically, the proportions are half riesling wine and half sparkling water, but in Speyer, he says, no one would accept a 50-50 mixture. Intead, they use the four-finger system: four fingers, widely spread, of wine, topped off with four fingers, turned flat, of water!

The protestant church is the "Dreifaltigkeitskirche," the Church of the Holy Trinity. It was consecrated on 31 October 1717, which is reformation day, the anniversary of Luther's nailing up his theses.

The protestant church is the "Dreifaltigkeitskirche," the Church of the Holy Trinity. It was consecrated on 31 October 1717, which is reformation day, the anniversary of Luther's nailing up his theses.

Speyer was one of the places that shook off the archbishop domination and became a free, independent city, answerable only to the emperor. At the reformation, the emperor gave the prince electors and the free cities the right to choose their own religion. Speyer went protestant, and the church was therefore built in baroque style, which was "in" at the time.

For once, the interior of the protestant church is more ornate than that of the Catholic cathedral—baroque was notriously "busy" and Romanesque classically simple.

The vaulted ceilings are beautifully painted.

The vaulted ceilings are beautifully painted.

The pulpit is especially intricately carved, but of course, as in all the churches we saw, it is at the side, partway down the nave from the altar. The first few pews are therefore double-faced, like the seats in some train cars, so that when the priest moved to the pulpit, the occupants of those pews could file around to the other side and sit facing him rather than craning their necks!

Just outside the church door, this small yucca was blooming in the middle of a patch of lilies of the valley.

Just outside the church door, this small yucca was blooming in the middle of a patch of lilies of the valley.

The protestant church stands at right angles to the axis of the cathedral, just a couple of blocks away, and where the streets leading from their doors cross is this statue of Jacob the pilgrim, a gift is a gift from the catholic bishop to the city, on its 2000th anniversary. Some members of our group asked the guide whether its placement was meant as a challenge to the protestants, but he assured us that, no, it was intended as a sign of reconciliation. It is actually on a route to Santiago de Campostela, though it apparently displays only a few of the scallop shells that usually mark the route. Jacob, Santiago, St. Jacques, and St. James are all names for the same saint, always marked with his pilgrim's floppy hat, walking staff, water gourd, and scallop shell.

Our next destination was the Judenhof, the old Jewish courtyard. On the way, the guide pointed out that all the street trees in the city are numbered and registered, so that the urban forester can manage them effectively. I wonder if that means there's a public database on line where you can look up a tree by number to find out what kind it is?

Our next destination was the Judenhof, the old Jewish courtyard. On the way, the guide pointed out that all the street trees in the city are numbered and registered, so that the urban forester can manage them effectively. I wonder if that means there's a public database on line where you can look up a tree by number to find out what kind it is?

The ruins in the Judenhof date from the middle ages. In 1084, Speyer's bishop invited Jews from neighboring towns to come to Speyer to settle. The usual reasons are cited—the city was building a new cathedral and needed to arrange major financing. In return the bishop offered the Jewish community rights and protections they couldn't get anywhere else in Europe. The guide showed us the ruins of the synagogue, consecrated in 1104. The view at the right here is as we approached the site.

Here, at the left, is a more direct view into the area of the synagogue. Illustrated panels on the far side show how it looked when it was still standing. More detailed panels that I didn't capture in these shots show complete floor plans and give explanatory text in German, French, and English.

Here, at the left, is a more direct view into the area of the synagogue. Illustrated panels on the far side show how it looked when it was still standing. More detailed panels that I didn't capture in these shots show complete floor plans and give explanatory text in German, French, and English.

At the right, we're looking down into the women's prayer wall, which adjoined the synagogue (added 50 years after it was built). Women could gather there and listen to the service through small barred and curtained windows that opened between the two. Two of them are barely visible on either side of the white bill cap in the foreground.

The site had no room for a Jewish cemetery, but a section of the city's medieval cemetery, about a mile away, was set aside for Jewish burials.

Both the synagogue and the women's prayer hall were destroyed in 1689. The guide didn't say so, but that date sounds like Louis XIV again to me. He was an equal-opportunity wrecker. He overlooked the mikvah, though, which is in its original condition.

Here at the left is a nearer view of the plexiglas canopy, visible at the left in the previous photo, that was constructed over the ruins of the mikvah (ritual bath). It was both a rain water and a groundwater mikvah until construction of the canopy excluded rain but is now solely groundwater. It's the oldest documented mikvah in Europe, consecrated in 1120.

Here at the left is a nearer view of the plexiglas canopy, visible at the left in the previous photo, that was constructed over the ruins of the mikvah (ritual bath). It was both a rain water and a groundwater mikvah until construction of the canopy excluded rain but is now solely groundwater. It's the oldest documented mikvah in Europe, consecrated in 1120.

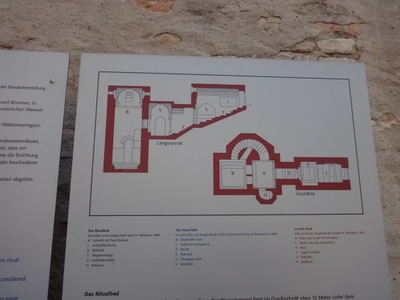

At the right are a floor plan and a vertical section showing the mikvah's shape and construction. To reach the water table, the builders had to dig down 33 feet. As the vertical section shows, you have to walk down a short flights of stone stairs to a wide spot that accommodates a couple of waiting benches, then down another short flight to a rectangular chamber. Off the chamber is a tiny semicircular changing alcove with a small bench in it. From there, you continue down a narrow spiral staircase (opposite the changing alcove) to the bath itself in the final chamber.

At the left here is a view of the entrance as you start down the stairs. Vertical shafts along the way let in air and light.

At the left here is a view of the entrance as you start down the stairs. Vertical shafts along the way let in air and light.

In the rectangular chamber are large windows looking through into the final chamber and down onto the bath itself.

At the bottom of the spiral stair, there's no landing—the stairs continue right into the water—and because several of us were on the stair at once, I had to get the shot at the left over the shoulders of the people in front of me.

At the bottom of the spiral stair, there's no landing—the stairs continue right into the water—and because several of us were on the stair at once, I had to get the shot at the left over the shoulders of the people in front of me.

Back up in the large chamber, the sills of the windows were too high and wide to afford much of a view, but I held my camera out over the space and got the shot at the right, looking down into the pool below. The arch is the lower end of the spiral stair. The level of the water rises and falls with the water table, which in turn rises and falls with the Rhine (or vice versa).

Like Jewish communities all over Europe, this one suffered the occasional progrom, but it persisted until the 16th century, when it was driven out. Another community formed in 1810 and persisted into the 20th century, but in 1940, the last jewish residents of Speyer were sent to a internment camp in the south of France for a year and a half and then to a German concentration camp and died in the gas chambers in 1942.

In the 1990's, the local community's 40 members went to Manheim for a modern mikvah, though I understand that if you live more than 1000 m from the mikvah you are freed from the obligation of using it. The community began to grow again in 1996 when Jewish refugee families from behind the iron curtain settled here, and the cornerstone of the new synagogue was laid in 2008. Interestingly, some of the many variant spellings of the town's original name "Spira" gave rise to the modern name Shapiro.

On the way back to the ship, the guide pointed out the old town hall, recognizable by its balcony, and the municipal building, which sports a clock face. The city has had its offices in the latter since 1748, and some residents apparently say that the same bureaucrats occupy still them.

Along the river, a greenfinch was calling in the trees, and crazies zooming around the Rhine on jetskies.

Back on the ship, the lunch options were not terribly location appropriate. Besides the salad bar, I had the baby back ribs (on the theory that, yes, the Germans eat a lot of pork, often including the ribs, though they don't usually slather them with barbecue sauce). They were pretty good and appealed to me more than the Scandinavian baby-shrimp sandwich. I don't remember whether I also had the corn chowder starter (not very German, that). For dessert, I had the banana split. The other choices were the fruit cup and the even more American brownie with ice cream on top. The banana split, as you can see, consisted of a split banana with vanilla ice cream and chocolate sauce—not even authentically American! At least the chocolate sauce was a good one.

Back on the ship, the lunch options were not terribly location appropriate. Besides the salad bar, I had the baby back ribs (on the theory that, yes, the Germans eat a lot of pork, often including the ribs, though they don't usually slather them with barbecue sauce). They were pretty good and appealed to me more than the Scandinavian baby-shrimp sandwich. I don't remember whether I also had the corn chowder starter (not very German, that). For dessert, I had the banana split. The other choices were the fruit cup and the even more American brownie with ice cream on top. The banana split, as you can see, consisted of a split banana with vanilla ice cream and chocolate sauce—not even authentically American! At least the chocolate sauce was a good one.

We remained in Speyer during the afternoon, so some people went ashore in search of shopping or to visit a museum. I stayed put and worked on transcribing my notes in the lounge, where Program Director Devin gave a talk on "Germany Today." He wasn't as organized (or, I'm afraid) as interesting as the previous day's speaker, but he did start by showing a great animated video map of Germany's changing borders over the centuries. I'm afraid I dozed off a couple of times later in the talk, so I don't have much to show in the way of notes on it.

The only photos I took all afternoon were of a passing day boat and the shot at the right here (taken during dinner) of the cooling towers of a nuclear power plant. Not sure whether it was one of Germany's remaining seven or one of France's

Just before our ceremonial dinner we had, as usual, the day's briefing on the following day's activities, and because this was the one where they went over disembarkation details, it was longer, and they requested that at least one person per stateroom show up.

It was only Saturday, and we would not actually disembark until Monday morning, but Viking always holds the farewell dinner and the disembarkation briefing a day early so that everyone can spend the last evening calmly packing up and getting ready. During the briefing, the ship left Speyer for Strasbourg.

According to the briefing, when we got back to our staterooms that evening, we would find not only the Viking Daily but a detailed schedule explaining who would go where when and what color tags we should put on our luggage, as well as a "welcome to Zurich" letter with all the schedules and departure times for flights home.

On Sunday, we planned to do the Strasbourg walking tour in the morning and the optional Alsatian wine tasting trip in the afternoon, then on Monday, we would do the Basel city tour in the morning but not the all-day "Highlights of the Alps" bus tour, which would have precluded the Basel tour.

We therefore got Orange paper tags to put on our luggage, on which we wrote our names and stateroom numbers. People who got green or blue tags would also start with the Basel tour but would be a different buses and might not do the wine tasting.

People who got brown tags would go off to the alps instead of Basel, but like us once they left the ship on Monday morning would next see their luggage in their hotel rooms in Basel.

People who planned to go on for the two-day extension in Zermatt after Basel and Zurich also received black tags for use then.

On Monday morning, everyone had to set their packed luggage outside their staterooms by 6:00 a.m. and vacate their staterooms by 8:30 a.m. The bus to the Alps would leave at 8:00 a.m. and that for the Basel tour at 9:15 a.m. (Bring your hand luggage and your Quietvox with you. Remember to empty your room's safe, especially of your passport.) The reason we had to be out of our staterooms so early was that the next group of passengers, for the cruise headed back toward Paris, would be boarding that same afternoon, and the staff needed the time to service the rooms. Between now and then, please check in at reception to make sure your credit card is on file, to avoid the rush to pay right at the end.

Since our last cruise, Viking had instituted a few policy on gratuities, where they charge you a set amount per day, which you can alter if you like. We went with the default.

But all that was for Monday. Back to Saturday night's farewell dinner, which was excellent.

The reginoal specialties were were radish salad with pumpernickel, sautéed char (a fish) with lemon mashed potatoes and black olive and tomato salsa, and Sachertorte.

The reginoal specialties were were radish salad with pumpernickel, sautéed char (a fish) with lemon mashed potatoes and black olive and tomato salsa, and Sachertorte.

On the regular menu, the starters were crab cake with scallion remoulade (which I chose; that's it on the left) and cream of pumpkin soup.

The main courses were risotto with zucchini, burrata, and truffles with lemon zest and roast chateaubriand with sauce Béarnaise, Lyonnaise potatoes, and glazed veggies. I had the latter, shown in the right photo. It was great!

The dessert was a soft-centered chocolate cake, which David chose, but both it and the Sachertorte were too chocolate for me, so I just had the ice cream of the day, which was pistachio.

The dessert was a soft-centered chocolate cake, which David chose, but both it and the Sachertorte were too chocolate for me, so I just had the ice cream of the day, which was pistachio.

During dessert, the waiter brought us a dish of chocolate-dipped strawberries.

During dessert, the waiter brought us a dish of chocolate-dipped strawberries.